| Armstrong 100-ton gun | |

|---|---|

"Rockbuster" at Napier of Magdala Battery, Gibraltar | |

| Type | Naval gun Coast defence gun |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1877-1906 |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Elswick Ordnance Company |

| Unit cost | £16,000[1] (£176,000 today) |

| No. built | 15[2] |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 103 tons |

| Barrel length | bore: 362.9 inches (9.22 m) (20.5 calibres)[3] |

| Shell | HE, AP, Shrapnel, 2,000 pounds (910 kg)[3] |

| Calibre | 450-millimetre (17.72 in)[3] |

| Recoil | 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in) |

| Elevation | 10° 30' |

| Traverse | 150° |

| Muzzle velocity | 1,548 feet per second (472 m/s)[4] |

| Maximum firing range | 6,600 yards (6,000 m) |

The 100-ton gun (also known as the Armstrong 100-ton gun)[5] was a 17.72 inches (450 mm) rifled muzzle-loading (RML) gun made by Elswick Ordnance Company, the armaments division of the British manufacturing company Armstrong Whitworth, owned by William Armstrong. The 15 guns Armstrong made were used to arm two Italian battleships and, to counter these, British fortifications at Malta and Gibraltar.

Origins

Around 1870 the largest gun made by UK firms was the 320 mm RML (rifled, muzzle-loading) gun, with a mass of 38 long tons (38.6 t), firing an 818-pound (371 kg) projectile capable of piercing 16.3 inches (410 mm) of mild steel at 2,000 yards (1,800 m). This weapon was adequate for the needs of the time, but the progress of gun technology was very rapid. French industries soon made a 420 mm (17 in), 76 t (75 long tons; 84 short tons) gun. This led the Royal Navy to ask for an 81 t (80 long tons; 89 short tons) gun.

Armstrong, the main British artillery producer, began a project for creation of an even larger weapon, an 18 in (460 mm) gun, also called the '100 ton'. Armstrong offered it to the Royal Navy, which rejected the gun, deeming it too heavy and costly.

Description

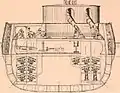

These new artillery pieces were enormous weapons for their time. Their weight was comparable to that of the much later Iowa-class 406 mm (16.0 in)/50cal guns, even though their barrels were quite short. They were muzzle-loading guns, with a rifled tube and rigid mount. Each gun required a crew of 35 men, including 18 men to handle the ammunition.

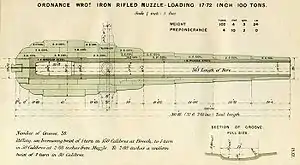

The gun was 9.953 m (32.65 ft) long. The barrel's maximum outer diameter was 1.996 m (6 ft 6.6 in), which reduced to 735 mm (28.9 in) at the muzzle. The construction method of an inner steel tube surrounded by multiple wrought iron coils,[6] was very complex, with several structures containing one another. The internal barrel was 30 feet 3 inches (9.22 m) long, or 20.5 calibers. The weight of the gun was 103,888 kg (229,034 lb), or about 100 tons.

Firing was mechanical or electrical, with an optical system for aiming.

The gun crews could fire a projectile once every six minutes.[7] Muzzle velocity was 472 m/s (1,550 ft/s) and maximum elevation was 10° 30'. At maximum charge 204 kg (450 lb)?) and maximum elevation, a projectile could achieve a range of only 5,990 m (19,650 ft), but at that distance the projectile could still pierce 394 mm (15.5 in) of steel (it is not clear if it was mild or hardened).

The weight of the mount was: 20,680 kg (45,590 lb) (mobile mounts with 18 wheels), 24,118 kg (53,171 lb) (platform) and 2,032 kg (4,480 lb) (base). The platform was sloped at 4 degrees to slow the recoil. On the platform mount, hydraulic systems powered chains that traversed the guns through an arc of 150 degrees; another hydraulic system provided elevation.

Ammunition

This was a second-generation RML gun, equipped with polygroove rifling and firing only studless ammunition with automatic gas-checks for rotation.

Projectiles were of three types, all weighing 2,000 pounds (910 kg) and having a diameter of 17.7 inches (450) mm:

- Armour-piercing (AP) Palliser, 44 inches (1.12 m) long, steel forward section, capable of piercing 21 in (0.53 m) of steel at 2,000 yd (530 mm at 1,800 m). with a 32-pound (14.5 kg) explosive internal charge.

- High explosive (HE) Common, 48+1⁄2 inches (1.23 m) long, with thinner walls and a 78-pound (35 kg) HE charge.

- Shrapnel shell: 45 inches (1.1 m) long, with a charge of only 5 pounds (2.3 kg) HE, but also 920 bullets of 4 ounces (110 g) each.

Firing charges were polygonal in shape, with 399 x 368 mm maximum width and length. They were made of 1 cwt (51 kg (112 lb)) 'Large Black Prism' propellant, and four or five were needed for every shell fired at maximum power. The recoil was 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in) as two hydraulic pistons in the rear part of platform absorbed the remaining energy.

Service

Sale to Italy

After the reunification of Italy, the Regia Marina began an innovative program to field the best and most powerful battleships of the time, the first being the Duilio-class, armed with 380 mm guns. They were already very powerful, but in February 1874 when the UK started to build HMS Inflexible, armed with 406 mm (16.0 in) guns, Italian admirals called for even more powerful guns, to hold the lead in battleship design.

On 21 July 1874, Armstrong signed a contract with Italy to deliver eight of its 100-ton guns, enough to arm Duilio and her sister-ship Dandolo. During firing trials on 5 March 1880, one of Duilio's guns cracked while firing at the maximum charge. At the suggestion of the British Army, it was officially established that the maximum practical charge was 204 kg (450 lb) and not 255 kg (562 lb).

British response

The Italian contract shocked British authorities, who had the Malta naval base to defend. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 had rendered Malta the most important British base in the Mediterranean. Although Malta's defenses included 320 mm (13 in) guns, this left Malta poorly defended against a possible attack from Duilio-class ships. This was a worrying problem because Francesco Crispi, one of the key architects of the Italian reunification, had called Malta "Italia irredenta" ("Unredeemed Italy").

The British feared that Duilio and Dandolo, which were already well-armored, could fire on Malta's shore batteries, destroying them one after the other, while keeping outside the effective range of the batteries' guns. But the British Army's concerns had no immediate effect on London bureaucracy; until the Italians launched Duilio in May 1876, London made no decision. The Royal Navy finally responded, requesting proposals from British arms manufacturers for a gun capable of piercing 36-inch steel at 1000 yd (900 mm at 900 m). The manufacturers returned with designs for immense guns of 163, 193, and 224 tons.

In December 1877, Simmons, chief of Malta defenses, was called to London to discuss the issue. He asked for four guns comparable to Duilio's at 3,000 yd (2,700 m). Due to the emergency, it was decided that the fastest and simplest solution was to quit designing the bigger guns and to buy the same weapons as those on Duilio, because generally a shore battery with the same caliber guns as a vessel retains an advantage over the vessel.[8] Four guns were requested in March 1878 and manufacture started in August; in the meantime Duilio had been conducting sea trials since 1877.

When Gibraltar's commanders heard of these big guns they too asked for some, which they obtained. Two of the four guns ordered for Malta would go to Gibraltar instead.

Malta service

HMS Stanley, a cargo vessel specially adapted for the task, delivered Malta's two guns. One gun was placed in Cambridge Battery, which was ready in 1886, and the other in Rinella Battery, which was completed in 1884. Cambridge received its gun on 16 September 1882 but only mounted it on 20 February 1884. Rinella received its on 31 July 1883 and mounted it on 12 January 1884. By this time, the Duilio-class ships had been operational for around seven years.

The work to make these machines serviceable was so great that until 1885 there were no firing tests. The first ammunition load comprised all the models available, including 50 AP and 50 HE shells. Shrapnel, once fired, was not replaced, being considered less effective. Between 1887 and 1888 activity stopped due to the need to rework hydraulic systems, but nevertheless the guns were considered quite reliable, serving for more than 20 years.

The careers of the guns were unspectacular, as no Italian battleship threatened Malta after their installation. The Malta guns were phased out in 1906, as was the remaining gun at Gibraltar. All had fired their last shots a few years before in 1903 or 1904.

During the First World War the guns at Malta were supposedly made ready for use when SMS Goeben was known to be nearby. Although the 100 t (98 long tons; 110 short tons) guns were powerful, modern weapons would have totally outclassed them: the range and rate of fire were too low, as modern 280–305 mm (11.0–12.0 in) guns had a range of over 15–20 km (9.3–12.4 mi) and a rate of fire of one shot every 30 seconds. Goeben would have had no difficulty firing on Malta's guns, if required to.

Gibraltar service

The first battery built for the guns in Gibraltar was Napier of Magdala, on Rosia Bay, and the second, called Victoria Battery, was placed one kilometer north. Construction started in December 1878, with the first ready in 1883 and the second in 1884.

HMS Stanley also delivered Gibraltar's two guns. The first gun arrived on 19 December 1882 and the second on 14 March 1883. These two guns were ready on their mounts in July and September 1883.

The first firings took place in 1884, but the weapons were not fully operational until 1889 due to hydraulic system problems. The barrel on the gun at Napier cracked during firing trials; this was because the crew had managed to stress the gun by firing one shot every 2.5 minutes. The wrecked gun was not easily repairable so it was used as a foundation for a building. The gun at Victoria Battery was moved to Napier, which the military deemed the more effective site.

The two surviving guns

The guns at Napier of Magdala Battery and at Fort Rinella are still intact and one can visit them. The guns were too costly to demolish and were left as junk, but both were later restored to display condition. Fort Rinella is under the guardianship of Fondazzjoni Wirt Artna - the Malta Heritage Trust. The pink paint on the Fort Rinella gun was added only recently; originally they were not painted at all.

Gallery

17.72 in (45.0 cm) projectile

17.72 in (45.0 cm) projectile Twin turret, Duilio

Twin turret, Duilio RML 17.72 in (45.0 cm), Gibraltar

RML 17.72 in (45.0 cm), Gibraltar RML 17.72 in (45.0 cm), Gibraltar

RML 17.72 in (45.0 cm), Gibraltar- Firing and loading video, model

Citations

- ↑ Brassey 1882, Page 95

- ↑ Italy : 8 for Duilio and Dandolo, 1 for Spezia defences, 2 spare. Britain : 2 for Malta, 2 for Gibraltar. Campbell, "British Super-Heavy Guns".

- 1 2 3 Text Book of Gunnery, 1902. Table XII, Page 337

- ↑ Firing 2000 lb projectile with 450 lb Prism powder propellant. Text Book of Gunnery, 1902. Table XII, Page 337.

- ↑ Roger Possner (1 July 2009). The Rise of Militarism in the Progressive Era, 1900-1914. McFarland. p. 218. ISBN 9780786454112.

- ↑ "Building Great Guns.; Herr Krupp's Latest Work – an 80-ton Breech-loader Costing $100,000". The New York Times. 21 May 1877.

- ↑ "TBD". The Journal of the Royal Artillery. 126–127: 40. 1999.

- ↑ Schull (1901), pp. 144-5.

References

- Text Book of Gunnery, 1902. LONDON : PRINTED FOR HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE, BY HARRISON AND SONS, ST. MARTIN'S LANE Archived 12 July 2012 at archive.today

- Brassey, Sir Thomas (1882) The British Navy, Volume II. London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Caruana, Joseph, The British 100 t guns, Storia militare magazine n.22, July 1995.

- Handbook for RML 17.72 inch gun, 1887, HMSO publications.

- Hughes, Q., Malta: A Guide to the Fortifications and Britain in the Mediterranean: the defense of her Naval stations

- Schull, Lieut. Herman W. (1901) "Spanish Ordnance in the Defense of Havana". Journal of the United States Artillery, Vol. 15, No. 2, Whole No. 48, pp. 129–146.

External links

- NJM Campbell, BRITISH SUPER-HEAVY GUNS

- Video of 100-ton gun being fired at Fort Rinella, Malta on YouTube

- photo of 100-ton gun automatic gas-check @ BBC website (accessed 2016-09-03)

- Animation of firing cycle