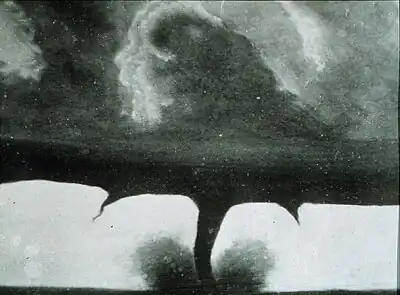

An F4 tornado that occurred near Howard, South Dakota. | |

| Type | Tornado outbreak |

|---|---|

| Duration | August 28, 1884 |

| Tornadoes confirmed | ≥ 6 |

| Max. rating1 | F4 tornado |

| Duration of tornado outbreak2 | ~ 31⁄2 hours |

| Fatalities | ≥ 7 fatalities, ≥ 2 injuries |

| Damage | [nb 1] |

| Areas affected | Dakota Territory |

| 1Most severe tornado damage; see Fujita scale 2Time from first tornado to last tornado | |

On August 28, 1884, a tornado outbreak, including a family of least five strong tornadoes, affected portions of the Dakota Territory within present-day South Dakota. Among them was one of the first known tornadoes to have been photographed, an estimated F4 on the Fujita scale, that occurred near Howard and exhibited multiple vortices. Another violent tornado also occurred near Alexandria, and three other tornadoes were also reported. A sixth tornado also occurred in present-day Davison County. In all, the tornadoes killed at least seven people and injured at least two others. Contemporary records and survivors' recollections indicate that the storms were F3 or F4 on the Fujita scale,[1][2] but cannot currently be verified, as official records begin in 1950.[nb 2][nb 3][nb 4]

Confirmed tornadoes

| FU | F0 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 1 | ? | ? | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | ≥ 6 |

August 28 event

| F# | Location | County / Parish | State | Time (UTC) | Path length | Max. width | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F2 | Carthage to W of Howard | Miner | SD | 20:00–? | 20 miles (32 km) | Unknown | This was the first of five tornadoes to form from a supercell that tracked across portions of five counties in present-day South Dakota.[13] Tornado destroyed a farmhouse and a barn, killing up to 30 cattle nearby. One person may have died.[14] |

| F3 | E of Huron | Beadle, Sanborn | SD | 21:15–? | 20 miles (32 km) | 100 yards (91 m) | 1 death – Tornado destroyed six or more barns and farmhouses. One person was injured.[14] |

| F4 | NNW of Forestburg to W of Howard to Long Lake | Sanborn, Miner, Hanson | SD | 22:00–? | 30 miles (48 km) | 400 yards (370 m) | 1 death – This was one of the first tornadoes of which there is a photograph.[15] The photographer was F. N. Robinson, who observed the tornado from a street in the town of Howard, about 3 km (1.9 mi) east of the storm track.[1] There was also another photographer from Huron who took multiple photographs of the same tornado an hour earlier. However, they were lost or destroyed during the engraving process. Tornado obliterated a home near Forestburg and killed at least 30 cattle. One person was injured. Two or more tornadoes may have been involved.[14] |

| F4 | Alexandria to S of Bridgewater | Hanson, Hutchinson | SD | 22:30–? | 25 miles (40 km) | 600 yards (550 m) | 4 deaths – Tornado demolished one farm, located south of Bridgewater. All fatalities occurred there. One person was found 1⁄2 mi (0.80 km) away.[14] |

| F2 | W of Sioux Falls | Minnehaha | SD | 23:30–? | 5 miles (8.0 km) | 80 yards (73 m) | 1 death – Tornado affected three farmsteads, one of which it destroyed, along with barns on the other farmsteads.[14] |

| FU | Mitchell | Davison | SD | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Tornado reported.[13] |

See also

Notes

- ↑ All losses are in 1884 USD unless otherwise noted.

- ↑ An outbreak is generally defined as a group of at least six tornadoes (the number sometimes varies slightly according to local climatology) with no more than a six-hour gap between individual tornadoes. An outbreak sequence, prior to (after) the start of modern records in 1950, is defined as a period of no more than two (one) consecutive days without at least one significant (F2 or stronger) tornado.[3]

- ↑ The Fujita scale was devised under the aegis of scientist T. Theodore Fujita in the early 1970s. Prior to the advent of the scale in 1971, tornadoes in the United States were officially unrated.[4][5] While the Fujita scale has been superseded by the Enhanced Fujita scale in the U.S. since February 1, 2007,[6] Canada utilized the old scale until April 1, 2013;[7] nations elsewhere, like the United Kingdom, apply other classifications such as the TORRO scale.[8]

- ↑ Historically, the number of tornadoes globally and in the United States was and is likely underrepresented: research by Grazulis on annual tornado activity suggests that, as of 2001, only 53% of yearly U.S. tornadoes were officially recorded. Documentation of tornadoes outside the United States was historically less exhaustive, owing to the lack of monitors in many nations and, in some cases, to internal political controls on public information.[9] Most countries only recorded tornadoes that produced severe damage or loss of life.[10] Significant low biases in U.S. tornado counts likely occurred through the early 1990s, when advanced NEXRAD was first installed and the National Weather Service began comprehensively verifying tornado occurrences.[11]

- ↑ All dates are based on the local time zone where the tornado touched down; however, all times are in Coordinated Universal Time and dates are split at midnight CST/CDT for consistency.

- ↑ Prior to 1994, only the average widths of tornado paths were officially listed.[12]

References

- 1 2 Snow, John T. (1984). "Early Tornado Photographs". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 65 (4): 360–364. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1984)065<0360:ETP>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1520-0477.

- ↑ Grazulis 1993, pp. 630–2

- ↑ Schneider, Russell S.; Brooks, Harold E.; Schaefer, Joseph T. (2004). Tornado Outbreak Day Sequences: Historic Events and Climatology (1875-2003) (PDF). 22nd Conf. Severe Local Storms. Hyannis, Massachusetts: American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- ↑ Grazulis 1993, p. 141.

- ↑ Grazulis 2001a, p. 131.

- ↑ Edwards, Roger (5 March 2015). "Enhanced F Scale for Tornado Damage". The Online Tornado FAQ (by Roger Edwards, SPC). Storm Prediction Center. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ↑ "Enhanced Fujita Scale (EF-Scale)". Environment and Climate Change Canada. 6 June 2013. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ↑ "The International Tornado Intensity Scale". Tornado and Storm Research Organisation. 2016. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ↑ Grazulis 2001a, pp. 251–4.

- ↑ Edwards, Roger (5 March 2015). "The Online Tornado FAQ (by Roger Edwards, SPC)". Storm Prediction Center: Frequently Asked Questions about Tornadoes. Storm Prediction Center. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ↑ Cook, A. R.; Schaefer, J. T. (August 2008). Written at Norman, Oklahoma. "The Relation of El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) to Winter Tornado Outbreaks". Monthly Weather Review. Boston: American Meteorological Society. 136 (8): 3135. Bibcode:2008MWRv..136.3121C. doi:10.1175/2007MWR2171.1.

- ↑ Brooks, Harold E. (April 2004). "On the Relationship of Tornado Path Length and Width to Intensity". Weather and Forecasting. Boston: American Meteorological Society. 19 (2): 310. Bibcode:2004WtFor..19..310B. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(2004)019<0310:OTROTP>2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 "Winds". Monthly Weather Review. Boston: American Meteorological Society. 12 (8): 193. August 1884. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1884)12[193b:W]2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Grazulis 1993, p. 631

- ↑ "Oldest Known Photo of a Tornado - August 28, 1884". National Weather Service Forecast Office Peachtree City, GA. Peachtree City, Georgia: National Weather Service. Archived from the original on May 30, 2009. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

Sources

- Grazulis, Thomas P. (July 1993). Significant Tornadoes 1680–1991: A Chronology and Analysis of Events. St. Johnsbury, Vermont: The Tornado Project of Environmental Films. ISBN 1-879362-03-1.

- Grazulis, Thomas P. (2001a). The Tornado: Nature's Ultimate Windstorm. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3538-0.

- Grazulis, Thomas P. (2001b). F5-F6 Tornadoes. St. Johnsbury, Vermont: The Tornado Project of Environmental Films.