Surface weather analysis of the hurricane after moving over the southeastern U.S. on October 3 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 27, 1893 |

| Dissipated | October 5, 1893 |

| Category 4 hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | 130 mph (215 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 948 mbar (hPa); 27.99 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 2,000 |

| Damage | $5 million (1893 USD) |

| Areas affected | Louisiana, Mississippi, Southeastern United States |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1893 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The Chenière Caminada hurricane, also known as the Great October Storm, was a powerful hurricane that devastated the island of Cheniere Caminada, Louisiana in early October 1893. It was one of three deadly hurricanes during the 1893 Atlantic hurricane season; the storm killed an estimated 2,000 people,[1][2] mostly from storm surge. The high death toll ranks the hurricane as the deadliest hurricane in Louisiana history and the third deadliest hurricane in the continental U.S., behind only the 1900 Galveston hurricane and the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane.

The Cheniere Caminada hurricane was the tenth known hurricane of the 1893 Atlantic hurricane season. Its origins remain unclear as neither maritime nor land-based weather observations captured its formative stages. The official Atlantic hurricane database indicates that the storm formed in the western Caribbean Sea on September 27, after which the storm intensified into a hurricane and struck northeastern portions of the Yucatan Peninsula on September 29 before curving northward into the Gulf of Mexico. A genesis in the western Caribbean was also contemporaneously noted by the U.S. Weather Bureau as a possible origin for the system. Another assessment of the storm published in 2014 suggested that the hurricane may have originated in the Bay of Campeche, avoiding the Yucatan Peninsula entirely. The first clear indication that the hurricane existed came on October 1, when the storm was in the northern Gulf of Mexico and closing in on the coast of Louisiana as a small but formidable hurricane; the storm's effects were already being experienced by the time the hurricane was first detected. On the night of October 1–2, the hurricane made landfall on southeastern Louisiana near Cheniere Caminada at peak strength, with its 130 mph (215 km/h) winds ranking it as a low-end Category 4 hurricane on the modern Saffir–Simpson scale. The storm then made landfall on October 2 as a slightly weaker hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) near Ocean Springs, Mississippi. It weakened inland over the Southeastern U.S. and continued to decay after entering the open Atlantic at Cape Hatteras, after which it dissipated around October 5.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

Little is known about the early history of the Cheniere Caminada hurricane. Alluding to the lack of knowledge concerning the storm's genesis, the U.S. Weather Bureau referred to the storm as a "so-called Gulf [of Mexico] hurricane" in an article in the October 1893 issue of the Monthly Weather Review. In the same article, the Weather Bureau speculated that the storm could have originated closer to Mexico or Honduras from a long trough of low pressure, but also noted that the contemporaneous wind observations along the Gulf Coast could lend credence to a sudden emergence of the hurricane in the gulf as late as the morning of October 1.[3] In the official Atlantic hurricane database sanctioned by the World Meteorological Organization, the storm is listed as beginning on September 27 in the western Caribbean Sea northeast of the border between Nicaragua and Honduras. The nascent system strengthened into a hurricane the next day and on September 29 and reached the equivalent of a low-end Category 2 hurricane intensity on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale with estimated maximum sustained winds of 100 mph (160 km/h). Tracking towards the northwest, the storm then traversed the northeastern parts of the Yucatan Peninsula and weakened slightly before moving into the Gulf of Mexico, where it restrengthened and curved towards the north and later northeast.[4][5]

Despite the prior hurricane intensity, only after October 1 – when rain from the storm was already moving onshore the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico – did weather observations clearly indicate that a hurricane existed.[3] The Weather Bureau had been unaware of the storm, predicting southeasterly winds and fair conditions following "light showers" on the Gulf coast for the night of October 1.[6] In reviewing and revising the tracks of historical storms maintained by the National Climatic Center, meteorologist José Fernández-Partagás found that the storm's listed positions prior to October 1 could not be reviewed due to a "lack of suitable information" and made no changes to the preexisting track in the database.[7][8] A new analysis conducted by meteorologist Michael Chenoweth of Atlantic tropical cyclones in the late 19th century, published in the Journal of Climate in 2014, lists the storm as having originated in the Bay of Campeche on September 27, after which the storm tracked northeast and bypassed the Yucatan Peninsula before entering the north-central Gulf of Mexico where the presence of the storm was first clearly resolved.[3][9]

By October 1, the storm was already a strong hurricane; in the official Atlantic hurricane database the storm is listed as beginning the day as the equivalent of a Category 2 hurricane. Further intensification ensued, and the storm reached its peak intensity early on October 2 with maximum sustained winds of 130 mph (215 km/h), making the storm equivalent to a low-end Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale.[4] Hurricane force winds began to spread onshore at dusk on October 1 and at around 08:00 UTC (3:00 a.m. CDT) on October 2 the hurricane made landfall on southeastern Louisiana near Cheniere Caminada at peak strength.[5][10][11] Weather instruments in the path of the storm were all blown down or destroyed, leaving no surviving complete record of the winds and rain associated with the landfalling hurricane.[3] While not directly measured, a central barometric pressure of 948 mbar (hPa; 27.99 inHg) was estimated by the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project of the Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory to have accompanied the hurricane at landfall based on extrapolations from later measurements. The hurricane was likely small upon making landfall, with the estimated 14 mi (23 km) radius of maximum wind being smaller than the average Atlantic storm at a similar intensity and latitude.[7] The center of the hurricane then passed between New Orleans, Louisiana, and Port Eads, Louisiana, before making landfall on the coast of Mississippi near Ocean Springs later on October 2.[3][12]

The storm had weakened by the time of its Mississippi landfall, with weather observations indicating that the storm's maximum sustained winds had declined to around 110 mph (175 km/h), making the storm comparable to a modern high-end Category 2 hurricane upon its encounter with Mississippi.[7] A central barometric pressure of 970 mbar (hPa; 28.64 inHg) was recorded onboard the schooner B. Frank Neally at Moss Point, Mississippi; a period of near-calm coincided with the lowest air pressure.[3][7] The storm then weakened as it progressed inland, diminishing into a tropical storm as it tracked over Georgia and the Carolinas.[5] It reached Cape Hatteras and continued out to the Atlantic by October 5 where it later dissipated.[3] The storm or its remnants may have persisted afterwards; the barque Comorin encountered a storm at an unspecified location along its voyage from Hamburg to Bermuda between October 7–9 that may have been a continuation of the Cheniere Caminada hurricane.[8]

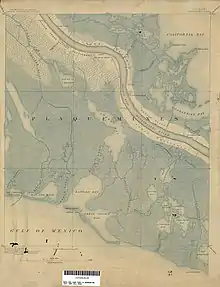

Impact

According to the National Hurricane Center, the Cheniere Caminada hurricane killed around 2,000 people, of which approximately 1,100–1,400 occurred onshore.[13] Contemporaneous enumerations of the fatalities provided death tolls ranging between 1,884 and 2,448, including 779 deaths in Cheniere Caminada, Louisiana, and 250 deaths in Grand Lake, Louisiana.[10] Most of the deaths occurred in southeastern Louisiana, particularly around the Mississippi River Delta and in Plaquemines Parish; the Weather Bureau reported that over 1,500 of those fatalities were the result of drowning.[3] This death toll ranks the hurricane as the deadliest in Louisiana history and – alongside the Sea Islands hurricane earlier in 1893 – as among the deadliest to ever strike the continental U.S., eclipsed by only the 1900 Galveston hurricane and the 1928 Okeechobee hurricane.[13][14] The swath of coastal damage spanned 500 mi (800 km), extending from Louisiana's Timbalier Bay eastward to Pensacola, Florida.[10]

The hurricane exacted its greatest impacts in southeastern Louisiana between New Orleans and Port Eads. There, the combination of high winds and storm surge wrought significant impacts, including the complete destruction of property and much of the area's crops such as orange, sugar, and rice;[3][8] around 60 percent of the orange crop in Plaquemines Parish was destroyed.[10] Crop damage was considerable on both sides of the Mississippi River and outlying islands were stripped of their vegetation.[8][10] Scores of buildings were destroyed, leaving behind only their foundations while the residual debris lay scattered.[6] The damage toll associated with property losses amounted to around $5 million.[10] The storm brought with it a significant tidal surge that swept across southeastern Louisiana.[3] The storm tide at Cheniere Caminada reportedly reached 20 ft (6.1 m) high.[7] Storm tide heights also reportedly reached 16 ft (4.9 m) high along the Chandeleur Islands and 15 ft (4.6 m) along Louisiana's other bays.[10] However, modeling conducted by the Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory using the Sea, Lake, and Overland Surge from Hurricanes model (SLOSH) indicated that a storm with the estimated intensity and size of the hurricane could only produce at most a storm tide reaching 8 ft (2.4 m) in height. Nonetheless, the storm surge was sufficient to inundate much of low-lying southeastern Louisiana.[7] Though instrumentation in the storm's path failed to withstand the intense conditions,[3] observers in southeastern Louisiana estimated winds exceeding 100 mph (160 km/h) at Pointe à la Hache and on the Chandeleur Islands.[8]

Cheniere Caminada – at the time a fishing village with a population of around 1,500 – bore the brunt of the storm.[15] The New York Times reported that Cheniere Camianda and Grand Isle had "shared the fate of Last Island" and that the resulting disaster had surpassed the 1856 Last Island hurricane.[8] The Thibodaux Sentinel described Cheniere Caminada as having been "swept out of existence."[15] The storm surge had submerged Cheniere Caminada under 6 ft (1.8 m) of water within minutes, cresting to a depth of around 8 ft (2.4 m).[16] Over half of the community's residents perished in the hurricane, either swept away by the torrent of seawater or crushed by the collapse of their homes.[15] Several mutilated corpses were found in lagoons, hanging in trees, and scattered among debris.[6] Sixty-two people survived under the remaining roof of a mostly destroyed home.[15] Many others survived clinging onto floating debris. Only four of Cheniere Caminada's 450 homes remained following the hurricane.[17]

There was one avenue of safety, and that was to seek the upper stories of the houses, but even that chance for escape was lost, when the wind and waves combined shook the frail habitations, which rocked to and fro and creaked and groaned under the repeated attacks of the furious elements. Soon the houses were being demolished, wrecked, and carried away. The wind shifted to the southeast, and for hours shrieked with redoubled fury. Above the thundering voice of the hurricane could be heard the despairing cries, the groans and the frantic appeals for help of the unfortunate victims.

— Pere Grimaux, as quoted by Rose C. Falls, Cheniere Caminada or The Wind of Death: The Story of the Storm in Louisiana (1893)

Grand Isle was also heavily impacted; 27 people were killed there.[6] The storm surge first began to inundate parts of the island at 10 p.m. CT, beginning gradually before escalating to a sudden and destructive wave that razed structures on Grand Isle prior to the passage of the storm's eye.[6][10] At the height of the storm, the island was submerged under 9 ft (2.7 m) of water.[8] Summer homes and hotels along Grand Isle were all destroyed.[10] The Chandeleur Island Light was tilted by several feet during the storm, with waves reaching high enough to batter and wash over the lighthouse's lantern 50 ft (15 m) above sea level;[10] 39 people were killed on the Chandeleur Islands.[6] The Barataria Bay Light and the Lake Borgne Light also suffered heavily, with the latter losing its roof due to strong winds and the former nearly being destroyed. Two hundred people survived the storm after sheltering at the Port Pontchartrain Light. Entire communities were wiped out by the hurricane, including Bohemia and Shell Beach.[8][10] One person survived on a makeshift raft and was rescued 100 mi (160 km) away from Cheniere Camianda where they were initially located. The Catholic church in Buras, Louisiana, was sheared from its supporting pillars and destroyed. The state's quarantine station, located in Buras, was also destroyed. Only two homes remained standing in Buras.[10] At least 200 deaths occurred along Bayou Cook, where homes were leveled.[8] Significant damage also occurred in the towns of Doullut, Grand Prairie, Home Place, Neptune, Ostrica, Point Pleasant, and Venice.[10]

The strong winds generated by the storm were felt as far west as Abbeville.[10] The storm's effects in New Orleans were first felt at 6:30 p.m. CT on the evening of October 1 and lasted through the overnight hours, resulting in flooding within the city.[3][10] The highest documented wind gust in the city proper was 48 mph (77 km/h), though the recording anemometer was knocked out of commission after sampling the gust at 8:20. Another anemometer in the West End recorded a wind gust of 65 mph (105 km/h) before it too succumbed to the conditions.[3]

Many vessels known and unknown were sunk in the hurricane throughout coastal Louisiana and Mississippi including[18][19]

- SS Joe Webre (steamship)

- SS Alice McGuigan (schooner): Also listed as Alice McGuigin.

- SS Angeline (schooner)

- SS New Union (schooner)

- SS Rosella Smith (bark)

- SS Young American (lugger)

- SS Annie E. B (bark)

- SS Laura B. (sloop)

- SS Three Brothers (lugger)

- SS Alice (sloop)

- SS Bertha (schooner)

- SS Sunny (lugger)

- SS Premier (schooner)

- SS Centennial (schooner)

- SS Pecourt (schooner)

- SS Rosalie (lugger)

- SS Nikita (Austrian bark)

Name confusion

The storm is named after a Louisiana village that bears the name of a Spanish sugar planter, Francisco Caminada.[20] Some sources give the name of the village as “Caminadaville,” while others misspell the name Chenière Caminada as “Chenier Caminada” or “Chenier Caminanda” (with an extra n). The village and other settlements on the island were nearly all destroyed.

Today the town of Cheniere Caminada is located in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana.

See also

- 1893 Sea Islands hurricane

- Hurricane Katrina (2005)

- Hurricane Ida (2021)

References

- Citations

- ↑ Blake, Eric S; Landsea, Christopher W; Gibney, Ethan J; National Climatic Data Center; National Hurricane Center (August 30, 2011). The deadliest, costliest and most intense United States tropical cyclones from 1851 to 2010 (and other frequently requested hurricane facts) (PDF) (NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS NHC-6). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. p. 47. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ↑ Christine Gibson Archived 2010-12-05 at the Wayback Machine "Our 10 Greatest Natural Disasters," American Heritage, Aug./Sept. 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Atmospheric Pressure (expressed in inches and hundredths)" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Washington, D.C.: United States Weather Bureau. 21 (10): 272–273. October 1893. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1893)21[269c:APEIIA]2.0.CO;2. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- 1 2 "1893 Hurricane Not Named (1893271N16278)". International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship.

- 1 2 3 "125th Anniversary of the Chenière Caminada hurricane". Hurricane Research Division. Miami, Florida: Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. October 2, 2018. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Plaisance, E. Charles (1973). "Chénière: The Destruction of a Community". Louisiana History. Louisiana Historical Association. 14 (2): 179–193. JSTOR 4231318. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Landsea, Chris; Anderson, Craig; Bredemeyer, William; Carrasco, Cristina; Charles, Noel; Chenoweth, Michael; Clark, Gil; Delgado, Sandy; Dunion, Jason; Ellis, Ryan; Fernandez-Partagas, Jose; Feuer, Steve; Gamanche, John; Glenn, David; Hagen, Andrew; Hufstetler, Lyle; Mock, Cary; Neumann, Charlie; Perez Suarez, Ramon; Prieto, Ricardo; Sanchez-Sesma, Jorge; Santiago, Adrian; Sims, Jamese; Thomas, Donna; Lenworth, Woolcock; Zimmer, Mark (2006). "Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Metadata). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 12345 09/27/1893 M= 9 10 SNBR= 311 NOT NAMED XING=1 SSS=9. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Fernández-Partagás, José (August 31, 1996). "Year 1893" (PDF). Storms of 1891-1893 (Report). A Reconstruction of Historical Tropical Cyclone Frequency in the Atlantic from Documentary and other Historical Sources Part IV: 1891–1900. Coral Gables, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Hurricane Research Division. pp. 58–62. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ↑ Chenoweth, Michael (December 1, 2014). "A New Compilation of North Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, 1851–98*". Journal of Climate. American Meteorological Society. 27 (23): 8674–8685. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00771.1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Roth, David (July 2012). "The Deadliest Hurricane in Louisiana History: Chenier Caminanda, October 1893" (PDF). Louisiana Hurricane History (Report). Camp Springs, Maryland: National Weather Service. pp. 26–27. Retrieved June 20, 2022 – via Louisiana State University.

- ↑ "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "October 1, 1893: Chenière Caminada hurricane hits Louisiana and Mississippi". Mississippi History Timeline. Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- 1 2 Blake, Eric S.; Gibney, Ethan J. (August 2011). The Deadliest, Costliest, and Most Intense United States Tropical Cyclones From 1851 to 2010 (and Other Frequently Requested Hurricane Facts) (PDF) (NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS NHC-6). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. p. 7. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- ↑ "Cheniere Caminada hurricane of 1893". Louisiana Hurricanes. Louisiana State University. January 31, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 Hall, Christie (September 22, 2016). "Cheniere Caminada's "Great October Storm"". Country Roads. Country Roads Magazine. Retrieved June 22, 2022.

- ↑ Falls 1893, p. 8.

- ↑ Falls 1893, p. 10.

- ↑ Falls 1893.

- ↑ Gilbert, Troy (2019). "Taking the Helm: The Black Captains of the Gulf Coast and the Unnamed Hurricane of 1893".

- ↑ Chase, John. "Frenchmen, Desire, Good Children: . . . and Other Streets of New Orleans!", Pelican Publishing, October 31, 2001. p195.

- Sources

- Falls, Rose C. (1893). Cheniere Caminada or The Wind of Death: The Story of the Storm in Louisiana. New Orleans, Louisiana: Hopkins' Printing Office. Retrieved June 26, 2022 – via HathiTrust Digital Library.

Further reading

- Davis, Donald W. (1993). "Cheniere Caminada and the Hurricane of 1893". In Magoon, Orville T.; Wilson, W. Stanley (eds.). Coastal Zone '93: Proceedings of the Eighth Symposium on Coastal and Ocean Management, July 19-23, 1993 New Orleans, Louisiana. New York: ASCE. pp. 2256–2269. ISBN 0-87262-918-X.

- Falls, Rose C. (1893). Cheniere Caminada or The Wind Of Death: The Story Of The Storm In Louisiana. New Orleans: Hopkins' Printing Office. Retrieved 2009-07-15. NOTE: The title is incorrectly indexed in Google Books