.jpg.webp)

1917–1919 Brazil strike movement was a Brazilian industry and commerce strike started in July 1917 in São Paulo, during World War I, promoted by anarchist-inspired workers' organizations allied with the libertarian press.[1] From 1917 to 1919, a large strike movement shook the First Brazilian Republic, concentrated in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.[2] It culminated in several general strikes in 1917 and an attempted anarchist uprising in November 1918. The 1917 general strike is considered the first general strike in the labor history of Brazil, and marks the beginning of the period known as the five red years (quinquennio rosso).[3][4]

Social history

The 1917 general strike in Brazil was part of a process of politicization among Brazilian workers. This politicization took place partly thanks to the ideas and organizational principles brought to the country by European Italian and Spanish workers who immigrated to Brazil in search of better living conditions from the second half of the 19th century onwards. While the Spaniards remained in urban areas when they arrived in Brazil, the Italian immigrant families had different destinations. In the state of São Paulo, Italians began to replace slave labor on coffee plantations, albeit on a salaried basis, while in Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina, Italians were sent to the mountainous region where they were given plots of unworked land to develop productive activities, without knowing the specifics of the region's soils and climate.

Oreste Ristori, an important libertarian anti-immigration activist and journalist, points out the slave-like treatment given to Italian immigrants in the interior of São Paulo by the big landowners, a factor that made the workers move to the capital when possible.

In the vicinity of Araraquara, there is one of those many perpetual prisons called Fazenda São Luís, owned by that pearl of a bandit who goes by the name of José de Lacerda Abreu. (...) Scary scenes often take place in this perpetual prison. The poor inmates (that's what we have to call the settlers because they can't leave the farm, otherwise they'll be beaten or murdered) work for years without being paid. When they ask for their earnings, they are answered with insults and lashes (...) From this place of horror, nine settler families have managed to escape, facing all sorts of dangers. The others who remain would like to follow the example of the first, but since the Hacienda is surrounded by henchmen, they won't risk it.

— ROMANI p. 150

At the beginning of the 20th century, a considerable number of Italian immigrants left the system of servitude that prevailed on coffee plantations in the interior of São Paulo to work in factories in the capital. In urban areas, they began to take action against the precarious working conditions in the factories, the massive use of child labor and the working hours of more than 13 hours. In various cities, the Italians also came into contact with groups of Brazilian libertarian activists, as well as Spanish and Portuguese emigrants. Together these workers from different backgrounds founded various syndicates and workers organizations that made up the workers movement, fighting for basic labour rights such as vacations, decent wages, an eight-hour working day and a ban on child labor.[5]

The growing organization of the workers came to be viewed with a negative eye by Brazil's urban elites, who saw it as a threat to their interests. Faced with the organization of the subaltern classes, the elites began to adopt a homogenizing nationalist discourse, claiming that the foreign workers were turning against the country that had welcomed them. Government organizations and a large part of the media were mobilized against the workers in defence of the interests of the ruling classes: the first general strike held in 1906 was fought with energy by the then secretary of public security, Washington Luis.

At that time, anarcho-syndicalism was one of the majority trends in the European workers milieu and was also rapidly consolidating in American countries. In Brazil, the anarcho-syndicalists articulated different initiatives to confront the exploitation imbricated in the developmentalist project of the agrarian and urban elites, and the political class linked to them. In addition to the syndicates, they also founded nurseries, libertarian education schools, printing presses and newspapers. One of the aims of these initiatives was to spread the general strike among the exploited classes of urban workers and rural laborers as a strategy of struggle, not only for better living conditions, but also as a form of emancipation from the domination of the ruling classes.

Background

The period from 1917 to 1920 marked the peak of the strike movements in Brazil. Led by immigrants, mainly Italians, this process went into decline, mainly due to the incompatibility between the slogans of the movements, dictated by the organizers, and the real interests of the workers. With industrial and urban growth, working-class neighborhoods sprang up in several Brazilian cities. Mostly made up of foreign immigrants, life in these neighborhoods was quite precarious, reflecting the low wages of the workers, the exhausting working hours, the absolute lack of guarantees of labor laws, such as weekly rest, vacations and retirement.

The problems were many. In factories, for example, there was massive use of child labor, which was cheaper than adult labor. Many of the children employed ended up with one of their limbs mutilated by the machines and, like the other workers, had no right to medical treatment, insurance for accidents at work, etc.

In this context, the first demonstrations arose under the influence of socialist and anarchist ideas, which were driving international workers struggles. Both in Brazil and in other countries, they were fighting for immediate results (better working conditions and wages, for example) and for broader objectives, including the overthrow of the capitalist system and the establishment of a more egalitarian society.

The organization of workers resulted in the founding of syndicate associations and workers newspapers, making the movement stronger to face the many difficulties. Following the example of workers in other countries, demonstrations and strikes broke out in several states, especially in São Paulo, where the largest number of industries were concentrated.

In 1907, the city of São Paulo was paralyzed by a strike demanding: an eight-hour working day, vacation rights, a ban on child labor, a ban on night work for women, pensions and hospital medical care. The demonstration started by workers in the construction industry, the food industry and metalworkers ended up spreading to other categories and reaching several cities in the state, such as Santos, Ribeirão Preto and Campinas.

In 1917, a wave of strikes began in São Paulo at two textile factories owned by Cotonifício Rodolfo Crespi and, having been joined by civil servants, quickly spread throughout the city and then almost the entire country. It soon spread to Rio de Janeiro and other states, especially Rio Grande do Sul. It was led by workers and activists inspired by anarchist and socialist ideals, including several Italian and Spanish immigrants. The syndicates by branches and trades, the workers leagues and unions, the state federations, and the Brazilian Workers' Confederation (founded in 1906) inspired by anarchist ideals.

Political and economic context

With the outbreak of World War I, Brazil became an exporter of foodstuffs to the countries of the "Triple Entente"; these exports accelerated from 1915 onwards, reducing the supply of food available for domestic consumption and causing prices to rise. Between 1914 and 1923, wages had risen by 71% while the cost of living had increased by 189%; this represented a two-thirds drop in the purchasing power of wages. A worker's average wage of around 100,000 réis corresponded to a basic consumption that for a family with two children amounted to 207,000 réis. Child labor was widespread.[6]

...the general strike of 1917 can in no way be equated in any way with other movements that subsequently occurred as manifestations of the working class. No, absolutely not! The general strike of 1917 was a spontaneous movement of the proletariat without any direct or indirect interference from anyone. It was an explosive manifestation, a consequence of a long period of tormenting life for the working class. The scarcity of what was indispensable for the subsistence of the working people was allied to the insufficiency of their earnings; the normal possibility of legitimate demands for indispensable improvements in their situation came up against the systematic police reaction; workers' organizations were constantly assaulted and prevented from functioning; police stations were overcrowded with workers, whose homes were invaded and raided; any attempt by workers to meet provoked the brutal intervention of the police. Reaction prevailed in the most odious forms. The proletarian atmosphere was one of uncertainty, fear and anguish. The situation was becoming untenable.

General strike in São Paulo

Death of José Martinez

On July 9, a cavalry charge was launched against workers protesting outside the Mariângela factory in Brás, resulting in the death of the young Spanish anarchist José Martinez. His funeral attracted a crowd that went through the city accompanying the body to the Araçá cemetery where he was buried. Outraged and already prepared to strike, the workers of the textile industry Cotonifício Rodolfo Crespi, based in Mooca, went on strike, and were soon followed by other factories and working-class neighborhoods. Three days later, more than 70,000 workers joined the strike. Warehouses were looted, streetcars and other vehicles were set on fire and barricades were erected in the streets.

The burial of this victim of the reaction was one of the most impressive popular demonstrations ever seen in São Paulo. The funeral cortege set off from Rua Caetano Pinto, in Brás, and stretched like a human ocean all the way along Avenida Rangel Pestana to the then Ladeira do Carmo on the way to the City, under an impressive silence that took on the appearance of a warning. The main streets of the center were covered. The police were unwilling to surround the street junctions. The crowd broke through all the cordons and continued its impetuous march to the cemetery. At the graveside, speakers took turns in indignant expressions of repulsion at the reaction (...) On the way back from the cemetery, part of the crowd gathered for a rally in Praça da Sé; the other part went down to Brás, to Rua Caetano Pinto, where, in front of the house of the murdered worker's family, another rally was held.

Demands

A violent general strike had broken out in São Paulo. Hermínio Linhares in his book Contribuição à história das lutas operárias no Brasil says: "The peak of this period was the general strike of July 1917, which paralyzed the city of São Paulo for several days. The striking workers demanded a pay rise. Trade was closed, transportation came to a halt and the impotent government was unable to subdue the movement by force. The strikers took over the city for thirty days. Milk and meat were only distributed to hospitals, and even then with the authorization of the strike committee. The government abandoned the capital (...)."

.jpg.webp)

The workers leagues and corporations on strike, together with the Proletarian Defense Committee, decided on the night of July 11 to number 11 topics through which to present their demands.[8]

- - That all those arrested for strike action be released;

- - That the right of association for workers be respected in the most absolute way;

- - That no worker be dismissed for having actively and ostentatiously participated in the strike movement;

- - That the exploitation of minors under the age of 14 in factories, workshops, etc. be abolished;

- - That workers under the age of 18 should not be employed in night work;

- - That night work for women be abolished;

- - A 35% increase in wages below $5000 and a 25% increase for the highest wages;

- - That wages be paid on time, every 15 days, and no later than 5 days after the due date;

- - That workers be guaranteed permanent work;

- - An eight-hour working day and an English week;

- - A 50% increase for all overtime work.

Negotiations

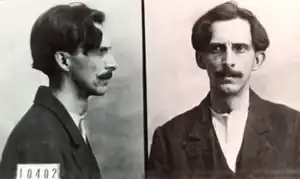

Around 70,000 people joined the movement. To defend the strike, the Proletarian Defence Committee was organized, with Edgard Leuenroth as one of its main spokesmen.

Edgard Leuenroth.. Photos taken at the police station on the occasion of the arrest in 1917.The situation was becoming increasingly serious with the clashes between the police and the workers. Only by overcoming all sorts of difficulties did the Proletarian Defense Committee manage to hold hasty meetings at various points in the city, sometimes under the overwhelming impression of the sound of gunfire in the vicinity. A meeting of the workers was essential if a decisive resolution was to be taken. Then came the suggestion of a general rally. How and where? And how to overcome the police sieges? But the situation, which was unfolding just as seriously, demanded it. The danger to which the workers were going to expose themselves was being transformed into a bloody reality in the police attacks in every neighborhood of the city, which also resulted in countless workers becoming victims of the reaction, whose only crime was to demand their right to survive. And the rally was held. Brás, the neighborhood where the movement had begun, was the most suitable place in the city, with the vast grounds of the old Mooca Hippodrome as the venue. The spectacle that the people of São Paulo witnessed was indescribable, as they were concerned about the seriousness of the situation. From all parts of the city, like veritable streams of people, the crowds came in search of the place that, for a long time, had served as a catwalk for the ostentation of expensive vanities, precisely in this corner of the city with a sky usually clouded by the smoke of the factories, at that moment empty of the workers who had gathered there to claim their indisputable right to a higher standard of living. It's not enough here to describe how that rally, considered one of the largest demonstrations in the history of the Brazilian proletariat, unfolded. Suffice it to say that the huge crowd decided that the movement would only cease when their demands, summarized in the Proletarian Defense Committee's memorial, were met.

Everardo Dias, in História das Lutas Sociais no Brasil (en: History of Social Struggles in Brazil), reports the events in this way:

São Paulo is a dead city: its population is alarmed, their faces show apprehension and panic, because everything is closed, without the slightest movement. Apart from a few hurried passers-by, there are only military vehicles on the streets, commandeered by Cia. Antártica and other industries, with troops armed with rifles and machine guns. Anyone standing in the street was ordered to shoot. In the factory districts of Brás, Moóca, Barra Funda and Lapa, there have been shootouts with groups of people; in some streets, barricades have already been set up with stones, old timber and overturned carts. The police don't dare pass by, because they're being shot at from rooftops and corners. The newspapers are full of news with almost no comment, but what is known is extremely serious, foreshadowing dramatic events.

— Fernando Dannemann[9]

Conclusion of strikes

The bosses gave an immediate pay rise and promised to study the other demands. The great victory was the recognition of the workers movement as a legitimate body, forcing the bosses to negotiate with the proletarians and take them into account in their decisions.

_2.gif)

The first meeting examined the memorial of workers' demands presented by the Proletarian Defense Committee, which the journalists' commission was tasked with taking to the state government. The second meeting was delayed due to the arrest of two members of the Proletarian Defense Committee as they left the newsroom after the first meeting. Understandings would be broken if these two elements were not immediately released. This resolution was passed on to the state president. The demand was met, the elements brought back to the newsroom, and the meeting could be held for a short time, as the government had not yet delivered its resolution. The resolution to grant the workers' demands was given via the Journalists' Commission, with the information that the workers arrested during the movement were already being released. Workers' rallies were held in various neighborhoods to decide on the resumption of work, which began the following day. São Paulo resumed its labor activities. The city resumed its usual appearance, but the sad memory remained of the victims who had left bereaved homes.

— Pedro Lucas Marques Lourenço[7]

The action of President Altino Arantes and Mayor Washington Luís

The president of the state of São Paulo at the time, Altino Arantes, would defend the interests of the ruling classes by attributing the strike to the infiltration of anarchists and communists, considered subversive, into the working class. However, in his message to the Legislative Congress of the State of São Paulo in 1918, he assumed that his government should act "as an element of mediation, concomitantly supporting the rights of employers and workers and watching over public order".

Altino also stated that, even after winning wage increases of 15 to 30%, anarchists were still inciting a new strike and a new wave of depredations. As a result of these events, he considered the generalization of strike movements to be dangerous and instituted, at police level, the prevention of general movements and the persecution of anarchists.Altino also reported that city hall employees, including nurses, were attacked by the strikers. The mayor of São Paulo, Washington Luís, then redoubled his efforts to keep public services running normally during the 1917 strike.

General strike in Rio Grande do Sul

Partly as a reflection of the mobilizations in other parts of the country, as well as inspired by the Russian Revolution, workers in Rio Grande do Sul organized themselves into syndicates and went on strike. Initially in the railroad sector, the strike quickly spread to industry and public services in the state's main cities. Strike organizations were quickly formed among the syndicates and workers organizations: the Popular Defense League in the city of Porto Alegre and the Popular Defense Committee in the city of Pelotas stand out for their work in raising awareness, propaganda and support for workers causes.

Workers activists sought to cover every possible area of the proletarian family's daily life. In addition to the companionship in the workplace, experiencing the same difficulties, suffering the same problems together: low wages, tiring working hours and unhealthy conditions - workers' militants (anarchists) provided various opportunities for culture, leisure and struggle through trade unions, social culture centers, popular schools and universities, newspapers, theaters, picnics. In this way, they built a "class culture" and a permanent identity of struggle. In Rio Grande do Sul, many of the 1917 militants were "trained" in the rationalist schools run by the libertarian militants.

— Correa, The 1917 General Strike and the LDP

On July 30, in Porto Alegre, the International Workers' Union issued a call for the public assembly to be held in Praça da Alfândega. The assembly promoted the formation of the Popular Defense League, in which workers' militants and organizers of the strike in the city stood out. Among them are Luis Derivi, secretary of the bricklayers, carpenters and related syndicate, and the printer Cecílio Vilar.

"...but this is not a time for conciliation, it's a time for struggle. The most justifiable struggle, the struggle for life. The workers must rise up as one man, to take to the streets to win the bread that is being stolen from us and to protest against the exploitation of the working class (...)"

— Cecílio Vilar

That same evening, the LDP released a note with the demands of the strike in the city.

Reducing the prices of basic necessities in general; Measures to prevent sugar hoarding; Establishment of a municipal slaughterhouse to supply the population with meat at a reasonable price; Creation of free markets in working-class neighborhoods; Compulsory sale of bread by weight and weekly fixing of the price per kilo; The municipality should charge 10% of rents for water supply and reduce to 5% the tenths of buildings whose value is less than 40$000. Compel the Power and Light company to set fares of 10 réis in accordance with the contract made with the municipality; Increase of 255 over current salaries; Generalization of the 8-hour working day; Establishment of the 6-hour working day for women and children."

Rio de Janeiro in 1918

The high degree of organization of the Brazilian working class that led to the general strike had yet another consequence: The anarchist insurrection of 1918 in Rio de Janeiro (at the time the national capital) was the result of the articulation of different syndicates and anarchist organizations, which were also inspired by the Russian Revolution and organized with the intention of overthrowing the central government. The initiative ended up with a military officer acting as an undercover agent provocateur, spying on the conspirators plans from a privileged location and reporting them to the state's repressive apparatus.

See also

References

- ↑ BREVE HISTÓRICO DO PCB (PARTIDO COMUNISTA BRASILEIRO)

- ↑ "1917-1918: The Brazilian anarchist uprising | libcom.org". libcom.org. Retrieved 2023-04-03.

- ↑ Pureza, Fernando (2019). "Food Riots, Strikes, and Looting in Brazil between 1917 and 1962: Defining the Repertoires of Working-Class Revolt". Zapruder world. Archived from the original on 2020-09-18.

- ↑ Costa, Camilla (28 April 2017). "1ª greve geral do país, há 100 anos, foi iniciada por mulheres e durou 30 dias". British Broadcasting Company. Archived from the original on 9 December 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ↑ Ristori, Oreste, Contra a Imigração, 1910

- ↑ "As Greves de 1917 no Brasil". CMI Brasil, FAG. 18 July 2007. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 TRAÇOS biográficos de um homem extraordinário. Dealbar [periodical], São Paulo, 17 Dec. 1968, year 2, n. 17.

- ↑ "Greve de 1917". 21 October 2006. Archived from the original on 3 August 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ↑ 1917 - Greves Operárias, DANNEMANN, Fernando Kitzinger.

Further reading

- Adelman, Jeremy (1998). "Political Ruptures and Organized Labor: Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico, 1916–1922". International Labor and Working-Class History. 54: 103–125. doi:10.1017/s0147547900006232. S2CID 145282282.

- Batalha, Claudio (2017). "Revolutionary Syndicalism and Reformism in Rio de Janeiro's Labour Movement (1906–1920)". International Review of Social History. 62 (S25): 75–103. doi:10.1017/s002085901700044x.

- Dulles, John W. F. (1973). Anarchists and Communists in Brazil, 1900–1935. Austin, TX/London: University of Texas Press.

- Maram, Sheldon L. (1977). "Labor and the Left in Brazil, 1890–1921: A Movement Aborted". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 57 (2): 254–272. doi:10.1215/00182168-57.2.254.

- Prado, Carlos (2017). "A Revolução Russa e o movimento operário brasileiro: confusão ou adesão consciente?". Revista Tilhas da História. 6 (12): 57–70.

- Toledo, Edilene (2017). "Um ano extraordinário: greves, revoltas e circulação de ideias no Brasil em 1917". Estudos Históricos (Rio de Janeiro). 30 (61): 497–518. doi:10.1590/s2178-14942017000200011.

- Wolfe, Joel (1991). "Anarchist Ideology, Worker Practice: The 1917 General Strike and the Formation of Sao Paulo's Working Class". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 71 (4): 809–846. doi:10.2307/2515765. JSTOR 2515765.

- Wolfe, Joel (1993). Working Women, Working Men: São Paulo and the Rise of Brazil's Industrial Working Class, 1900–1955. Durham, NC/London: Duke University Press.