The Portuguese discovery of the sea route to India was the first recorded trip directly from Europe to the Indian subcontinent, via the Cape of Good Hope.[1] Under the command of Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama, it was undertaken during the reign of King Manuel I in 1495–1499. Considered one of the most remarkable voyages of the Age of Discovery, it initiated the Portuguese maritime trade at Fort Cochin and other parts of the Indian Ocean, the military presence and settlements of the Portuguese in Goa and Bombay.[2][3]

Preparations of the trip

The plan for working on the Cape Route to India was charted by King John II of Portugal as a cost saving measure in the trade with Asia and also an attempt to monopolize the spice trade. Adding to the increasingly influential Portuguese maritime presence, John II craved for trade routes and for the expansion of the kingdom of Portugal which had already been transformed into an Empire. However, the project was not realized during his reign. It was his successor, King Manuel I, who designated Vasco da Gama for this expedition, while maintaining the original plan.

However, this development was not viewed well by the upper classes. In the Cortes de Montemor-o-Novo of 1495, an opposite view was visible over the journey that John II had so painstakingly prepared. This point of view was contented with the trade with Guinea and North Africa and feared the challenges posed by the maintenance of any overseas territories, and the cost involved in the launching and maintenance of sea lanes. This position is embodied in the character of The Old Man of Restelo that appears in Os Lusíadas of the Portuguese epic poet Luís Vaz de Camões, who opposed the boarding of the armada. Os Lusíadas is often regarded as the most important work of Portuguese literature. The work celebrates the discovery of a sea route to India by the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama.

Manuel I did not share that opinion. Keeping his predecessor's plan, he went ahead to equip the ships and chose Vasco da Gama as the leader of this expedition and the captain of the armada. According to the original plan, John II had appointed his father, Stephen da Gama, to head the armada; but by the time of implementing the plan, both were deceased.

Portuguese were after spices, but they were very expensive because it was an inconvenience to trade. For example, it was dangerous and time consuming to travel by land from Europe to India.[4] As a result, King John II of Portugal established a plan for ships to explore the coast of Africa to see if India was navigable via around the cape, and through the Indian Ocean. King João II appointed Bartolomeu Dias, on October 10, 1486, to head an expedition to sail around the southern tip of Africa in the hope of finding a trade route to India.[4] Dias helped in the construction of the São Gabriel and its sister ship, the São Rafael that were used by Vasco da Gama to sail past the Cape of Good Hope and continue to India.[4]

One of the sailors, Bartolomeu Dias passed the Cape of Good Hope and the southernmost point of Africa in 1488. He declared it possible to travel to India by going around Africa. The Portuguese were then able to make an immense profit by using their own ships to retrieve the spices.

This global expedition was launched on 8 July 1497. It concluded two years later with the entry of the ships back into the river Tagus, bringing with them the good news that bestowed on Portugal a prestigious maritime position.

The context

Spices were always considered the gold of the Indies. Cinnamon, ginger, cloves, black pepper and turmeric had long been products which were difficult to obtain in Europe and brought in by caravans and experienced merchants coming from the East.

A merchant of Lisbon describes the overland spice route as follows: Only the markets of Venice and Genoa then scattered these spices all over Europe, great in cost, and without guaranteed arrival.[5] In 1453, with the capture of the city of Constantinople by the Ottomans, the trade of Venice and Genoa reduced to a great degree. The advantage of the Portuguese to establish a sea route therefore virtually free of assault – however, covered in perils in the sea – showed itself rewarding and outlined a large income to the Crown in the future. Portugal directly linked the spice producing regions to their markets in Europe.

Around the year 1481, João Afonso of Aveiro attempted to undertake an exploration of the kingdom of Benin, and gathered information about an almost legendary prince Ogané, whose kingdom was located far to the east of Benin. He was thought to be Christian and one who enjoyed great respect and power. It was said the Benin kingdom where Ogané had his headquarters was twenty moons away in distance, which, according to the account of João de Barros, corresponds to two hundred fifty leagues.

Excited with this news, John II sent, in 1487, Frei António de Lisboa and Pedro de Montarroio to locate in the East new information that could find Prester John, which seemed to correspond, after all, to the description that came about the prince Ogané.[6] But the mission of those sent was merely to Jerusalem, because these two Portuguese were unaware of the Arabic language and hence feared to continue, and instead returned to Portugal.

Very carefully and secretly two young men of trust were prepared. They were Afonso de Paiva, of Castelo Branco, and Pêro da Covilhã. They began their journey and went through Valencia, Barcelon, Naples, Rhodes, Alexandria, Cairo and Aden. Here their paths separated: Afonso de Paiva headed to Ethiopia and Pêro da Covilhã to India. None of the men returned, but the information needed by John II was brought back to the kingdom, and with this came the support to serve the possible epic maritime adventure that lay ahead.

The travel plan predicted the safety of the route. For this, it was necessary to install trading posts along the way, and build fortresses. The mission was up to the captain of the armada who was provided with many gifts and equipment to brave the seas and diplomatic credentials and perseverance to create links with unknown monarchs who eventually were found along the way.

But it was not in the reign of King John II of that this project, which was already facing a strong opposition from the court, was initiated. It happened only in the time of his successor, Manuel I who incidentally did not share the general opinion about the sea routes being a good – if not the best – means to dominate trade with the East.

The navy

Among the sailors, were two interpreters Fernão Martins and Martim Afonso de Sousa, and two brothers, João Figueira and Pêro da Covilhã. In all, the crews comprised 170 men.

The sailors had sailing charts marked with the positions of the African coast known until then, quadrants, astrolabes of various sizes, tables with calculations – such as astronomical tables of Abraham Zacuto – needle and bobs. One of the ships was carrying groceries sufficient for three years: biscuits, beans, dried meats, wine, flour, olive oil, pickles and other items of pharmacy. Also planned were continuous replenishment along the coast of Africa. The trip to India was performed by three ships and another ship that carried supplies. These three ships had a captain and a pilot. The ship of groceries had only a captain. Two ships also had a scribe or writer. The first ship had a master.

The voyage

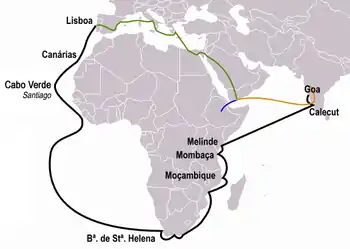

Thus began the expedition on 8 July 1497. The Lisbon shipping line to Cabo Verde was the usual one and the Indian Ocean is described by Álvaro Velho thus: "The coastal route until Malindi and direct passage from this port to Calicut". During this expedition, the latitudes were determined by solar observation, as stated by João de Barros.

Reports of the Daily Board (Diários de Bordo) of the ships note many unique experiences. Also found were a rich flora and fauna. Contact was made near the bay of St. Helena with tribes who ate sea lions, whales, gazelle meat and herbal roots; They walked covered with fur and their weapons were simple wooden spears of Zambujo and animal horns; They saw tribes who played rustic flutes in a coordinated manner, which was a surprising sight for the Europeans. Scurvy (vitamin C deficiency) affected the crew. They crossed into Mozambique with palm trees yielding coconuts.

Despite the adversities of a trip of this scale, the crew retained their curiosity and courage to achieve the feat and get along with people they encountered. To gather pace, they raided ships in search of pilots. With the prisoners, the Captain-General could trade, or put them to work.

It is known, thanks to the Portuguese humanist philosopher Damião de Góis, that during the trip five padrões were set in place. São Rafael, in the Bons Sinais river; São Jorge, Mozambique; the Holy Spirit in Malindi; Santa Maria, in Ilhéus, and São Gabriel, in Calicut. These monuments were meant to affirm the Portuguese sovereignty in these places so that other explorers who arrived later did not take the land for themselves as discoveries. The only one of these to survive to the present day is the Vasco da Gama Pillar in Malindi.[7]

Arrival in Calicut

On May 17, 1498, the fleet reached Kappakadavu, near Calicut, in the current Indian state of Kerala, thus having established the route via the Indian Ocean and managing to open the sea route from Europe to India.[8]

Negotiations with the local governor, Samutiri Manavikraman Raja, Zamorin of Calicut, were difficult. Vasco da Gama's efforts to obtain favorable commercial terms have been hampered by the different cultures and the low value of their gifts – in the West it was customary for kings to offer presents to the foreign envoys; in the East the kings were expected to be impressed with rich offerings. Goods presented by the Portuguese proved insufficient to impress the Zamorin and representatives of the Zamorin mocked their offers, while the Arab merchants established there resisted the possibility of unwanted competition.

Vasco da Gama's perseverance made him nevertheless initiate negotiations between him and the Zamorin, who was pleased with the letters of King Manuel I. Finally, Vasco da Gama managed to get an ambiguous letter of concession rights to trade.

The Portuguese eventually were able to sell their goods at a low price in order to acquire small amounts of spices and jewels to take to their kingdom. However the fleet eventually departed without warning after the Zamorin insisted that they left all their assets as collateral. Vasco da Gama kept his goods, but left a few Portuguese with orders to start a trading post.

Back in Portugal

On July 12, 1499, after more than two years since the beginning of this expedition, the caravel Berrio entered into the river Tagus, commanded by Nicolau Coelho, with the news that thrilled Lisbon: the Portuguese had finally reached India by sea. Vasco da Gama had fallen behind on Terceira Island, preferring to stay on with his brother who was seriously ill, thus foreclosing the celebrations and congratulations by the news.

Of the ships involved, only the São Rafael (St. Raphael) did not return. It was burnt due to its inability to maneuver, as a result of the reduced number of the crew as a result of diseases which killed about half the crew, such as scurvy which was felt acutely while crossing the Indian Ocean. Only 55 of the 148 men who were part of the armada survived the trip.[9]

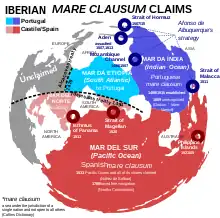

Vasco da Gama returned home on 31 August and was received by King Manuel I with contentment. He assigned him the title of Don and great rewards.[9] Manuel I hastened to break the news to the kings of Spain, both as a display of pride as also to warn that both the routes would be explored by the Portuguese Crown.[9]

Italian merchants spread the good news in Florence.

With the opening of the sea route to the East Indies by the Portuguese, the fall of the Venetian monopoly on the spice trade in Europe was inevitable and the resulting drop in prices of spices contributed to the commercial development of the continent.[10]

See also

References

- ↑ "Vasco da Gama reaches India".

- ↑ "Portuguese, The - Banglapedia". en.banglapedia.org. Archived from the original on 1 April 2017.

- ↑ Tapan Raychaudhuri (1982). The Cambridge Economic History of India: Volume 1, C.1200-c.1750. CUP Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-22692-9.

- 1 2 3 Luís de Carvalho, Sérgio (2017). A Children's History of Portugal. Dartmouth, MA: Tagus Press. p. 28. ISBN 9781933227795.

- ↑ "History of Portugal". www.historyworld.net. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- ↑ CCBB Rio (2007). Lusa: A Matriz Portuguesa. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. ISBN 9788560169016.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ 'Vasco da Gama Pillar', National Museums of Kenya website (accessed 19 July 2023)

- ↑ "Da Gama Discovers a Sea Route to India". National Geographic Society. 2014-04-29. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- 1 2 3 "Vasco da Gama – Exploration". History.com. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- ↑ "The Spice That Built Venice".