| Ebola virus epidemic in Sierra Leone | |

|---|---|

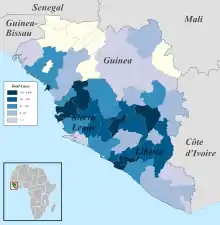

Map of Sierra Leone | |

Cropped satellite view of S. Leone | |

| Disease | Ebola virus |

| Confirmed cases | 14,061 (as of 25 October 2015)[1] |

Deaths | 3,955 |

An Ebola virus epidemic in Sierra Leone occurred in 2014, along with the neighbouring countries of Guinea and Liberia. At the time it was discovered, it was thought that Ebola virus was not endemic to Sierra Leone or to the West African region and that the epidemic represented the first time the virus was discovered there.[2] However, US researchers pointed to lab samples used for Lassa fever testing to suggest that Ebola had been in Sierra Leone as early as 2006.[3]

History of Ebola in Sierra Leone

| Articles related to the |

| Western African Ebola virus epidemic |

|---|

|

| Overview |

| Nations with widespread cases |

| Other affected nations |

| Other outbreaks |

In 2014, it was discovered that samples of suspected Lassa fever showed evidence of the Zaire strain of Ebola virus in Sierra Leone as early as 2006.[3] Prior to the current Zaire strain outbreak in 2014, Ebola had not really been seen in Sierra Leone, or even in West Africa among humans.[3] It is suspected that fruit bats are natural carriers of disease, native to this region of Africa including Sierra Leone and also a popular food source for both humans and wildlife.[3] The Gola forests in south-east Sierra Leone are a noted source of bushmeat.[4]

Bats are known to be carriers of at least 90 different viruses that can make transition to a human host.[5] However, the virus has different symptoms in humans.[5] It takes one to ten viruses to infect a human but there can be millions in a drop of blood from someone very sick from the disease.[6][7] Transmission is believed to be by contact with the blood and body fluids of those infected with the virus, as well as by handling raw bushmeat such as bats and monkeys, which are important sources of protein in West Africa. Infectious body fluids include blood, sweat, semen, breast milk, saliva, tears, feces, urine, vaginal secretions, vomit, and diarrhea.[8]

Even after a successful recovery from an Ebola infection, semen may contain the virus for at least two months.[9] Breast milk may contain the virus for two weeks after recovery, and transmission of the disease to a consumer of the breast milk may be possible.[10] By October 2014, it was suspected that handling a piece of contaminated paper may be enough to contract the disease.[11] Contamination on paper makes it harder to keep records in Ebola clinics, as data about patients written on paper that gets written down in a "hot" zone is hard to pass to a "safe" zone, because if there is any contamination it may bring Ebola into that area.[11]

One aspect of Sierra Leone that is alleged to have aided the disease, is the strong desire of many to have very involved funeral practices.[12] For example, for the Kissi people who inhabit part of Sierra Leone, it is important to bury the bodies of the dead near them.[12] Funeral practices include rubbing the corpses down with oil, dressing them in fine clothes, then having those at the funeral hug and kiss the dead body.[12] This may aid the transmission of Ebola, because those that die from Ebola disease are thought to have high concentrations of the virus in their body, even after they have died.[12]

For the 2001 outbreak of Sudan virus in Uganda, attending a funeral of an Ebola victim was rated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as one of the top three risk factors for contracting Ebola, along with contact with a family member with Ebola or providing medical care to someone with a case of Ebola virus disease.[13] The main start of the outbreak in Sierra Leone was linked to a single funeral in which the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates as many as 365 died from Ebola disease after getting the disease at the funeral.[14]

Bushmeat has also been implicated in spreading Ebola disease, either by handling the raw meat or through droppings from the animals.[15] It is the raw blood and meat that is thought to be more dangerous, so it is those that hunt and butcher the raw meat that are more at risk as opposed to cooked meat sold at market.[16] Health care workers in Sierra Leone have been warned not to go to markets.[17]

2014: Outbreak started

In late March 2014, there were suspected but not confirmed cases in Sierra Leone.[18] The government announced on 31 March 2014, that there were no cases in Sierra Leone.[19] Cases initially started appearing soon after the arrival of US researchers into the area. "After Ebola was first confirmed by laboratory tests in mid-March 2014, persistent rumours in the region linked the outbreak to a US-run research laboratory in Kenema, Sierra Leone (Wilkinson, 2017)."[20]

Spring 2014: Early cases

Two U.S. doctors who "followed all CDC and WHO protocols to the letter" contracted Ebola, and it is not clear how they got infected.[21]

By 27 May 2014, it was reported 5 people died from the Ebola virus and there were 16 new cases of the disease.[22][23] Between 27 May 2014, and 30 May the number of confirmed, probable, or suspected cases of Ebola went from 16 to 50.[24] By 9 June, the number of cases had risen to 42 known and 113 being tested, with a total of 16 known to have died from the disease by that time.[25]

The disease spread rapidly in Kenema, and the local government hospital was overwhelmed.[14] At that hospital, 12 nurses died despite having the world's only Lassa fever isolation ward, according to the U.N.[14] Many health are workers were infected at the state hospital, including beloved physician and hemorrhagic fever expert, Dr. Sheik Humarr Khan, and chief nurse Mbalu Fonnie. Khan and his colleagues had bravely provided care to patients with this devastating illness. [26]

Summer 2014: Continued growth, Dr. Khan dies

On 12 June, the country declared a state of emergency in the Kailahun District, where it announced the closure of schools, cinemas, and nightlife places; the district borders both Guinea and Liberia, and all vehicles would be subject to screening at checkpoints.[27][28] The government declared on 11 June, that its country's borders would be closed to Guinea and Liberia; but many local people cross the borders on unofficial routes which were difficult for authorities to control.[29][30] Seasonal rains that fall between June and August interfered with the fight against Ebola, and in some cases caused flooding in Sierra Leone.[31]

By 11 July 2014, the first case was reported in the capital of Sierra Leone, Freetown, however the person had traveled to the capital from another area of the country.[32] By this time there were over 300 confirmed cases and 99 were confirmed to have died from Ebola.[32] There was another case before the end of the month.[33]

On 29 July, well-known physician Sheik Umar Khan, Sierra Leone's only expert on hemorrhagic fever, died after contracting Ebola at his clinic in Kenema. Khan had long worked with Lassa fever, a disease that kills over 5,000 a year in Africa. He had expanded his clinic to accept Ebola patients. Sierra Leone's president, Ernest Bai Koroma, celebrated Khan as a "national hero".[34] On 30 July, Sierra Leone declared a state of emergency and deployed troops to quarantine hot spots.[35]

In August, awareness campaigns in Freetown, Sierra Leone's capital, were delivered over the radio and through loudspeakers.[36] Also in August, Sierra Leone passed a law that subjected anyone hiding someone believed to be infected to two years in jail. At the time the law was enacted, a top parliamentarian was critical of failures by neighboring countries to stop the outbreak.[37] Also in early August Sierra Leone cancelled league football (soccer) matches.[38]

September 2014: Exponential growth, quarantines

.jpg.webp)

Within 2 days of 12 September 2014, there were 20 lab-confirmed cases discovered in Freetown, Sierra Leone.[39] One issue was that residents were leaving dead bodies in the street.[39] By 6 September 2014, there were 60 cases of Ebola in Freetown, out of about 1100 nationwide at this time.[40] However, not everyone was bringing cases to doctors, and they were not always being treated.[40] One doctor said the Freetown health system was not functioning, and during this time, respected Freetown Doctor Olivette Buck fell ill and died from Ebola by 14 September 2014.[40][41] The population of Freetown in 2011 was 941,000.[42]

By 18 September 2014, teams of people that buried the dead were struggling to keep up, as 20–30 bodies needed to be buried each day.[43] The teams drove on motor-bikes to collect samples from corpses to see if they died from Ebola.[43] Freetown, Sierra Leone had one laboratory that could do Ebola testing.[43]

WHO estimated on 21 September, that Sierra Leone's capacity to treat Ebola cases fell short by the equivalent of 532 beds.[44] Experts pushed for a greater response at this time noting that it could destroy Sierra Leone and Liberia.[45] At that time it was estimated that if it spread through both Liberia and Sierra Leone up to 5 million could be killed;[46] the population of Liberia is about 4.3 million and Sierra Leone is about 6.1 million.

In an attempt to control the disease, Sierra Leone imposed a three-day lockdown on its population from 19 to 21 September. During this period 28,500 trained community workers and volunteers went door-to-door providing information on how to prevent infection, as well as setting up community Ebola surveillance teams.[47] The campaign was called the Ouse to Ouse Tock in Krio language.[48] There was concern the 72-hour lock-down could backfire.[49]

On 22 September, Stephen Gaojia said that the three-day lock down had obtained its objective and would not be extended. Eighty percent of targeted households were reached in the operation. A total of around 150 new cases were uncovered, but the exact figures would only be known on the following Thursday as the health ministry was still awaiting reports from remote locations.[50] One incident during the lock-down was when a burial team was attacked.[51]

On 24 September, President Ernest Bai Koroma added three more districts under "isolation", in an effort to contain the spread. The districts included Port Loko, Bombali, and Moyamba. In the capital, Freetown, all homes with identified cases would be quarantined. This brought the total areas under isolation to 5, including the outbreak "hot spots" Kenema and Kailahun which were already in isolation. Only deliveries and essential services would be allowed in and out. A sharp rise in cases in these areas was also noted by WHO.[52]

As of late September, about 2 million people were in areas of restricted travel,[53] which included Kailahun, Kenema, Bombali, Tonkolili, and Port Loko Districts.[54] The number of cases seemed to be doubling every 20 days, which led to the estimate that by January 2015 the number of cases in Liberia and Sierra Leone could grow to 1.4 million.[55]

On 25 September, there were 1940 cases and 587 deaths officially, however, many acknowledged under-reporting and there was an increasing number of cases in Freetown (the capital of Sierra Leone).[56]

WHO estimated on 21 September, that Sierra Leone's capacity to treat Ebola cases fell short by the equivalent of 532 beds.[44] There were reports that political interference and administrative incompetence had hindered the flow of medical supplies into the country.[57]

October 2014: Responders overwhelmed

By 2 October 2014, an estimated 5 people per hour were being infected with the Ebola virus in Sierra Leone.[58] By this time it was estimated the number of infected had been doubling every 20 days.[59] On 4 October, Sierra Leone recorded 121 fatalities, the largest number in a single day.[60] On 8 October, Sierra Leone burial crews went on strike.[61] On 12 October, it was reported that the UK would begin providing military support to Sierra Leone in addition to a major UK civilian operation in support of the Government of Sierra Leone.[62]

In October, it was noted hospitals were running out of supplies in Sierra Leone.[63] There were reports that political interference and administrative incompetence hindered the flow of medical supplies into the country.[57] In the week prior to 2 October there were 765 new cases, and Ebola was spreading rapidly.[64] At the start of October, there were nearly 2200 laboratory confirmed cases of Ebola and over 600 had died from it.[65] The epidemic also had claimed the life of 4 doctors and at least 60 nurses by the end of September 2014.[66] Sierra Leone limited its reported deaths to laboratory confirmed cases in facilities, so the actual number of losses was known to be higher.[11]

Sierra Leone was considering making reduced care clinics, to stop those sick with Ebola from getting their families sick with the disease and to provide something in between home-care and the full-care clinics.[67] These "isolation centers" would provide an alternative to the overwhelmed clinics.[67] The problem the country was facing was 726 new Ebola cases but less than 330 beds available.[68]

More than 160 additional medical personnel from Cuba arrived in early October, building on about 60 that had been there since September.[69] At that time there were about 327 beds for patients in Sierra Leone.[70] Canada announced it was sending a 2nd mobile lab and more staff to Sierra Leone on 4 October 2014.[71]

There were reports of drunken grave-diggers making graves for Ebola patients too shallow, and as a result wildlife came and dug up and ate at the corpses.[72] In addition, in some cases bodies were not buried for days, because no one came to collect them.[73] One problem was that it was hard to care for local health care workers, and there was not enough money to evacuate them.[74] Meanwhile, other diseases like malaria, pneumonia, and diarrhea were not being treated properly because the health system was trying to deal with Ebola patients.[75] On 7 October 2014, Canada sent a C-130 loaded with 128,000 face shields to Freetown.[76]

In early October 2014, a burial team leader said there were piles of corpses south of Freetown.[77] On 9 October, the International Charter on Space and Major Disasters was activated on Sierra Leone's behalf, the first time that its charitably repurposed satellite imaging assets had been deployed in an epidemiological role.[78][79] On 14 October 2014, 800 Sierra Leone peacekeepers due to relieve a contingent deployed in Somalia, were placed under quarantine when one of the soldiers tested positive for Ebola.[80]

The last district in Sierra Leone untouched by the Ebola virus declared Ebola cases. According to Abdul Sesay, a local health official, 15 suspected deaths with 2 confirmed cases of the deadly disease were reported on 16 October, in the village of Fakonya. The village is 60 miles from the town of Kabala in the center of the mountainous region of the Koinadugu district. This was the last district free from the virus in Sierra Leone. All of the districts in this country had then confirmed cases of Ebola.[81]

In late October 2014, the United Kingdom sent one of their hospital ships, the Royal Navy's Argus, to help Sierra Leone.[82] By late October Sierra Leone was experiencing more than twenty deaths a day from Ebola.[83] In October 2014, officials reported that very few pregnant women were surviving Ebola disease.[84] In previous outbreaks pregnant women were noted to have a higher rate of death with Ebola.[85]

Officials struggled to maintain order in one town after a medical team trying to take a blood sample from a corpse were blocked by an angry machete-wielding mob. They allegedly believed the person had died from high-blood pressure and did not want the body being tested for Ebola. When security forces tried to defend the medical team, a riot ensued leaving two dead. The town was placed on a 24-hour curfew and authorities tried to calm the situation down.[86] Despite this several buildings were attacked.[87]

On 30 October, the ship Argus arrived in Sierra Leone.[88] It carried 32 off-road vehicles to support Ebola treatment units.[89] The ship also carried three transport helicopters to support operations against the epidemic.[90] By the end of October 2014 there were over 5200 laboratory confirmed cases of Ebola virus disease in Sierra Leone.

On 31 October 2014, an ambulance driver in Bo District died of Ebola. His ambulance picked up Ebola patients (or suspected Ebola cases) and took them to treatment centers.[92]

November 2014: Continuing struggle

On 1 November, the United Kingdom announced plans to build three more Ebola laboratories in Sierra Leone. The labs helped to determine if a patient had been infected by the Ebola virus. At that time, it took as much as five days to test a sample because of the volume of samples that needed to be tested.[93]

On 2 November, a person with Ebola employed by the United Nations was evacuated from Sierra Leone to France for treatment. On 4 November, it was reported that thousands violated quarantine in search for food, in the town of Kenema.[94] On 6 November, it was reported that the situation was "getting worse" due to "intense transmission" in Freetown as a contributing factor; the capital city reported 115 cases in the previous week alone. Food shortages and aggressive quarantines were reported to be making the situation worse, according to the Disaster Emergency Committee.[95] Sierra Leone established call centers in Port Loko and Kambia, according to MSSL Communications as reported on 21 November;[96] this was in addition to the June hotline originally established.[97]

On 12 November, more than 400 health workers went on strike over salary issues at one of the few Ebola treatment centers in the country.[98] On 18 November, the supply ship Karel Doorman of the Royal Netherlands Navy (Koninklijke Marine) arrived in Freetown, with supplies. Its Captain-Commander, Peter van den Berg, took steps to reduce the chance of the crew contracting Ebola virus disease.[99]

The Neini Chiefdom in Koinadugu District was subject to isolation after Ebola cases.[100] On 19 November, it was reported that the Ebola virus was spreading intensely; "much of this was driven by intense transmission in the country's west and north", the WHO said.[101]

A British-built Ebola Treatment Centre which started in Kerry Town during November, generated some controversy because of its initially limited capacity. However, this was because they were following guidelines of how to safely open an Ebola treatment unit. This was the first of six planned treatment centres which, when completed, would be staffed by a number of NGOs.[102]

In mid-November the WHO reported that while all cases and deaths continued to be under-reported, "there is some evidence that case incidence is no longer increasing nationally in Guinea and Liberia, but steep increases persist in Sierra Leone".[103] On 19 November, it was reported that the Ebola virus was spreading intensely; "much of this was driven by intense transmission in the country's west and north", the WHO said.[101] The first Cuban doctor to be infected with the virus was flown to Geneva.[104] On 26 November, it was reported that due to Sierra Leone's increased Ebola transmission, the country would surpass Liberia in the total cases count.[105] On 27 November, Canada announced it would deploy military health staff to the infected region.[106] On 29 November, the President of Sierra Leone canceled a planned three-day shutdown in Freetown to curb the virus.[107]

December 2014

On 2 December, it was reported that the Tonkolili district had begun a two-week lockdown, "which was agreed in a key stakeholders meeting of cabinet ministers, parliamentarians and paramount chiefs of the district as part of efforts to stem the spread of the disease", according to a ministry spokesman. The move meant that a total of six districts, containing more than half of the population, were locked down.[108]

Sierra Leone indicated, in a report on 5 December, that about 100 cases of the virus were now being reported daily.[109] On the same day, it was further reported that families caught taking part in burial washing rituals, which can spread the virus, would be taken to jail.[110] On 6 December, a report indicated that the Canadian Armed Forces would send a medical team to the country of Sierra Leone to help combat the Ebola virus epidemic.[111]

On 8 December, the doctors in Sierra Leone went on strike, demanding better treatment for health care workers, according to Health Ministry spokesman Jonathan Abass Kamara.[112]

On 9 December, Sierra Leone authorities placed the Eastern Kono District in a two-week lock-down following the alarming rate of infection and deaths there. The lock down lasted until 23 December.[113] This followed the grim discovery of bodies piling up in the district. The WHO reported fear of a major breakout in the area. The district with 350,000 inhabitants buried 87 bodies in 11 days, with 25 patients dying in 5 days before the WHO arrived.[114]

On 12 December, Sierra Leone banned all public festivities for Christmas or New Year, because of the outbreak.[115] On 13 December, it was reported that the first Australian facility had been opened; "operations will be gradually scaled up to full capacity at 100 beds under strict guidelines to ensure infection control procedures are working effectively and trained staff ... are in place", one source indicated.[116]

Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders, in partnership with the Ministry of Health, carried out during December the largest-ever distribution of antimalarials in Sierra Leone. Teams distributed 1.5 million antimalarial treatments in Freetown and surrounding districts with the aim of protecting people from malaria during the disease's peak season. A spokesman said "In the context of Ebola, malaria is a major concern, because people who are sick with malaria have the same symptoms as people sick with Ebola. As a result, most people turn up at Ebola treatment centres thinking that they have Ebola, when actually they have malaria. It's a huge load on the system, as well as being a huge stress on patients and their families."[117]

Between 14 and 17 December Sierra Leone reported 403 new cases with a total of 8,759 cases on the latter date.[118][119] On 25 December, Sierra Leone put the north area of the country on lockdown.[120] By the end of December Sierra Leone again reported a surge in numbers, with 9,446 cases reported.[121][122]

On 29 December 2014, Pauline Cafferkey, a British aid worker who had just returned to Glasgow from working at the treatment centre in Kerry Town, was diagnosed with Ebola at Glasgow's Gartnavel General Hospital.[123][124]

2015: Outbreak continues

January 2015

On 4 January, the lockdown was extended for two weeks.[125] On this day the country reported 9780 cases with 2943 deaths. Among healthcare workers there were 296 cases with 221 fatalities reported.[126]

On 8 January, MSF admitted its first patients to a Treatment Centre (ETC) in Kissy, an Ebola hotspot on the outskirts of Freetown. Once the ETC is fully operational it will include specialist facilities for pregnant women.[127] By 9 January, the case load in the country exceeded 10,000, with 10,074 cases and 3,029 deaths reported.[128] On 9 January, it was reported that South Korea would send a medical team to Goderich.[129]

On 10 January, Sierra Leone declared its first Ebola-free district. The Pujehun district in the south east of the country reported no new cases for 42 days.[130]

February 2015

A worker at Kerry Town clinic was evacuated to the United Kingdom on 2 February 2015, after a needlestick injury.[131] On 5 February, it was reported that there was a rise in weekly cases for the first time this year.[132][133] The U.N. indicated that the sharp drop in cases had "flattened out" raising concern about the virus.[134]

March 2015

On 5 March, a report indicated cases in Sierra Leone continued to rise.[135] The government of Sierra Leone declared a three-day country-wide lock-down including 2.5 million people on 18 March.[136][137] The U.N. indicates the outbreak will be over by August of this year.[138]

The 3-day lock-down of over 6 million inhabitants revealed a 191% increase in possible Ebola cases. In Freetown alone 173 patients meeting the criteria for Ebola were discovered according to Obi Sesay from the National Ebola Response Center.[139]

Spring 2015

As of 12 May, Sierra Leone had gone 8 days without an Ebola case, and was down to two confirmed cases of Ebola.[140] The WHO weekly update for 29 July reported a total of only three new cases, the lowest total in more than a year.[141] On 17 August, the country had its first week with no new cases,[142] and one week later the last patients were released.[143]

August/September 2015

A new death was reported on 1 September after a patient from Sella Kafta village in Kambia District was tested positive for the disease after her death.[144] On 5 September, another case of Ebola was identified in the village among the approximately 1000 people currently under quarantine. A woman tested positive for the virus. The "Guinea ring vaccine" has been administered by a WHO team in the village since Friday 5 September.[145] On 8 September the head of the National Ebola Response Center confirmed new cases of Ebola. This brought the total from the village to four cases, with all of them being under the "high risk" contact cases with the death of the new index case in the village. In total four cases were then confirmed including the dead woman.[146]

On 14 September, the National Ebola Response Center confirmed the death of a 16-year-old in a village in the Bombali district. Swabs taken from the body tested positive for the disease. The village was placed under quarantine.[147] She had no history of traveling outside the village, and it is suspected that she contracted the disease from the semen of an Ebola survivor who was discharged in March 2015. Seven of her immediate contacts were taken to an Ebola treatment center, with a further three patients she had contact with at a health clinic.[148] A new study to be published in the New England Journal of Medicine indicates the possibility that the virus may lurk in the semen of survivors for up to six months. Nearly half of 200 patients tested had traces of the virus in their semen six months after surviving the disease.[149] On 7 November, the World Health Organization declared Sierra Leone Ebola-free.[150]

January 2016

Sierra Leone entered a 90-day period of enhanced surveillance which was scheduled to conclude on 5 February 2016, but due to a new case in mid-January it did not.[151] On 14 January, it was reported there had been a fatality linked to the Ebola virus. The case occurred in the Tonkolili district.[152] Prior to this case WHO had advised, "we anticipate more flare-ups and must be prepared for them ... massive effort is underway to ensure robust prevention, surveillance and response capacity across all three countries by the end of March."[153] On 16 January, it was reported that the woman who died of the virus may have exposed several individuals; the government announced that 100 people had been quarantined.[154] On the same day, WHO released a statement, indicating that originally the 90-day enhanced surveillance period was to end on 5 February. Investigations indicate the female case was a student at Lunsar in Port Loko district, who had gone to Kambia district on December the 28th until returning symptomatic. Bombali district was visited by the individual, for consultation with an herbalist, later going to a government hospital in Magburaka. WHO indicates there are 109 contacts, 28 of which are high risk, furthermore, there are three missing contacts.The source or route of transmission which caused the fatality is still unknown.[155] A second new case was confirmed on 20 January; the patient had contact with the previous fatality.[156] On 17 March, the WHO declared the country Ebola-free.[157]

Healthcare capacity

Long-term political factors contributed to the Ebola crisis including the acute dependency on external health assistance, patron-client politics, corruption and a weak state capacity.[158] Prior to the Ebola epidemic Sierra Leone had about 136 doctors and 1,017 nurses/midwives for a population of about 6 million people.[159] On 26 August, the WHO (World Health Organisation) shut down one of two laboratories after a health worker became infected. The laboratory was situated in the Kailahun district, one of the worst-affected areas. It was thought by some that this move would disrupt efforts to increase the global response to the outbreak of the disease in the district.[160]

"It's a temporary measure to take care of the welfare of our remaining workers", WHO spokesperson Christy Feig announced. He did not specify how long the closure would last, but said they would return after an assessment of the situation by the WHO. The medical worker, one of the first WHO staff infected by the Ebola Virus, was treated at a hospital in Kenema and then evacuated to Germany.[160][161] By 4 October 2014, it was announced he has recovered and left Germany.[162]

As the Ebola epidemic grew it damaged the health care infrastructure, leading to increased deaths from other health issues including malaria, diarrhoea, and pneumonia because they were not being treated.[163] The WHO estimated on 21 September that Sierra Leone's capacity to treat Ebola cases fell short by the equivalent of 532 beds.[44]

Death of health workers

On 27 August 2014, Dr. Sahr Rogers died from Ebola after contracting it working in Kenema.[165] Sierra Leone lost three of its top doctors by the end of August to Ebola.[166]

A fourth doctor, Dr. Olivette Buck, became ill with Ebola in September and died later that month.[167] Dr. Olivette Buck was a Sierra Leone doctor who worked in Freetown, who tested positive for Ebola on 9 September 2014, and died on 14 September 2014.[41] Her staff believes she was exposed in August. She eventually went to Lumley Hospital on 1 September 2014, with a fever, thinking it was malaria.[41] After a few more days of illness she was admitted to Connaught Hospital.[41]

By 23 September 2014, out of 91 health workers known to have been infected with Ebola in Sierra Leone, approximately 61 had died.[168]

On 19 October, the WHO reported 129 cases with 95 deaths of healthcare workers (125 / 91 confirmed).[169] On 2 November 2014, a fifth doctor, Dr. Godfrey George, a medical superintendent of Kambia Government Hospital died as a result of Ebola infection.[170] On 17 November 2014, a sixth doctor, Dr Martin Salia, died as a result of Ebola infection, after being transported by medevac to Nebraska Medical Center in the United States.[171]

On 18 November 2014, a seventh doctor, Dr Michael Kargbo, died in Sierra Leone. He worked at the Magburaka Government Hospital.[172]

Dr. Aiah Solomon Konoyeima was reported to have Ebola in late November 2014, which would make him the eighth physician to contract Ebola.[173] He was reported to have died from the disease on 7 December 2014, becoming what was reported as the tenth doctor to die from Ebola.[174]

On 26 November 2014, a ninth doctor, Dr. Songo Mbriwa, was reported to be sick with Ebola disease.[175] He was working at an Ebola treatment centre in Freetown.[175] He was one of the doctors that cared for the late Dr Martin Salia, who experienced a false-negative Ebola test, but did indeed have it and may have exposed others.[176]

On Friday 5 December, a senior health official announced the death of two of the country's doctors in one day. This brings the total number of doctors who have died from the disease in Sierra Leone to ten. Dr Dauda Koroma and Dr Thomas Rogers are the latest deaths among healthcare workers.[177] The two doctors were not in the front line of the Ebola battle and did not work in an Ebola treatment hospital.[178]

On 18 December, Dr. Victor Willoughby died from the disease after being tested positive for the disease on Saturday 6 December. The doctor died hours before he was to receive ZMAb, an experimental treatment from Canada, according to Dr. Brima Kargbo the country's chief medical officer. Dr. Victor Willoughby is the 11th doctor, and a top physician, to succumb to the disease.[179]

Evacuations

Since the beginning of the outbreak in Sierra Leone in late May 2014, several people have been evacuated. An increasing lack of hospital beds, medical equipment, and health care personnel made treatment difficult.On 24 August William Pooley, a British nurse, was evacuated from Sierra Leone. He was released on 3 September 2014.[180][181] In October 2014, he announced he would return to Sierra Leone.[182]

On 21 September 2014, Spain evacuated a Catholic priest who had contracted Ebola while working in Sierra Leone with Hospital Order of San Juan de Dios.[183] He died on 25 September in Madrid.[184] On 6 October 2014, a nurse who treated the priest tested positive for Ebola.[185] By 20 October 2014, the nurse seemed to have recovered after many days battling the disease in the hospital, with tests coming back negative.[186]

A doctor from Senegal contracted Ebola while working in Sierra Leone for the WHO, and was evacuated to Germany at the end of August 2014.[187] By 4 October 2014, it was announced he has recovered and returned to Senegal.[162]

In late September, a doctor working for an International Aid organization in Sierra Leone, was evacuated to Switzerland after potentially being exposed. He later tested negative for the disease.[188]

In late September 2014, an American doctor working in Sierra Leone was evacuated to Maryland, USA, after being exposed to Ebola.[189] "Just because someone is exposed to the deadly virus, it doesn't necessarily mean they are infected", said Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the NIH.[189] He was evacuated after a needle sticking accident and even developed a fever, but he was determined not to have Ebola and was released the first week in October 2014. After being discharged he remained at home under medical observation, checking his temperature twice a day for 21 days.[190]

In early October, a Ugandan doctor who contracted Ebola while working in Sierra Leone was evacuated for treatment to Frankfurt, Germany.[191] The doctor was working at Lakaa Hospital and flown out from Lungi Airport.[192]

On 6 October 2014, a female Norwegian MSF worker tested positive for Ebola virus and was subsequently evacuated to Norway.[193] Norwegian authorities reported that they had been granted a dose of the experimental biopharmaceutical drug ZMAb, a variant of ZMapp.[194][195][196] ZMapp has previously been used on 3 Liberian health workers, of which 2 survived.[197] It was also used on 4 evacuated westerners, of which 3 survived.[198][199][200][201][202][203] A U.N. employee was evacuated to France in early November 2014 after contracting Ebola.[204]

On 12 November 2014, Dr Martin Salia, a permanent resident of the United States, tested positive for Ebola while working as a specialist surgeon at the Connaught Hospital in Freetown. He is the sixth Sierra Leone doctor to have contracted Ebola virus disease. Initially he preferred to be treated at the Hastings Holding Centre by Sierra Leonean medical personnel, however on 15 November 2014, he was evacuated to the Nebraska Medical Center where his condition was reported as "still extremely critical" on 16 November.[205][206][207] On 16 November the hospital released a statement that he "passed away as a result of the advanced symptoms of the disease".[171]

On 18 November a Cuban doctor, Felix Baez, tested positive for Ebola and was due to be sent to Geneva for treatment. He later recovered. Baez was one of 165 Cuban doctors and nurses in Sierra Leone helping treat Ebola patients. There were a further 53 Cubans in Liberia and 38 in Guinea, making this the largest single country medical team mobilized during the outbreak.[208][209]

Confounding factors

Sierra Leonean government intransigence

On 5 October, The New York Times reported that a shipping container full of protective gowns, gloves, stretchers, mattresses and other medical supplies had been allowed to sit unopened on the docks in Freetown, Sierra Leone, since 9 August.[210] The $140,000 worth of equipment included 100 bags and boxes of hospital linens, 100 cases of protective suits, 80 cases of face masks and other items, and were donated by individuals and institutions in the United States.[210]

The shipment was organised by Mr Chernoh Alpha Bah, a Sierra Leonean opposition politician, who comes from Sierra Leonean President Ernest Bai Koroma's hometown, Makeni.[210] The New York Times reported that political tensions may have contributed to the government delay in clearing the shipping container, to prevent the political opposition from trumpeting the donations.[210]

Government officials stated that the shipping container could not be cleared through customs, as proper procedures had not been followed.[210] The Sierra Leonean government refused to pay the shipping fee of $6,500.[210] The New York Times noted that the government had already received well over $40 million in cash from international donors to fight Ebola.[210] The New York Times noted that in the 2 months that the shipping container remained on the docks in Freetown, health workers in Sierra Leone endured severe shortages of protective supplies, with some nurses having to wear street clothes.[210]

David Tam-Baryoh, a radio journalist, was held for 11 days when he and a talk show guest, an opposition party spokesperson, criticised how President Ernest Bai Koroma handled the Ebola outbreak in a live broadcast on 1 November 2014. The weekly show Monologue was taken off-air mid-show from the independently run Citizen FM.[211] He was arrested on 3 November and sent to the Pademba Road jail, after an executive order was signed by the president. On 14 November Sierra Leone's Deputy Information Minister Theo Nicol gave a statement that Baryoh had "been put on a ten thousand dollar bail by the Criminal Investigation Department after a statement has been taken from him".[212]

Amid concerns for his health, Tam-Baryoh apparently signed a confession to ensure his release from the prison, engineered by a committee made up of his lawyer, 2 journalists and a peace studies lecturer of the University of Sierra Leone. Rightsway International, an independent human rights group, has condemned President Koroma for allegedly dictating to the committee about obtaining the confession. A statement later released by the group read:[213]

Rightsway is disappointed that Tam Baryoh's forced confession has been published widely by pro-government media outlets and social networks. The publication of forced confessions is often used to discredit dissident news and information providers. This is a media propaganda tool used by dictatorial regimes, to avoid being exposed, investigated and punished for the grave violations of human rights.

Local conspiracy theories

- "The Ebola outbreak was sparked by a bewitched aircraft that crashed in a remote part of Sierra Leone, casting a spell over three West African countries – but a heavily alcoholic drink called bitter Kola can cure the virus."[214]

- "Some members of the community thought it was a bad spirit, a devil or poisoning."[215]

- At the beginning of the outbreak, many did not believe that the disease existed. "I thought it was a lie (invented) to collect money because at that moment I hadn't seen people affected in my community."[215]

Community violence

On 21 October, there was Ebola related violence and rioting in the eastern town of Koidu, with police imposing a curfew.[216] Local youth fired at police with shotguns after a former youth leader refused health authorities permission to take her relative for an Ebola test.[216] Several buildings were attacked and youth gangs roamed the streets shouting "No more Ebola!"[217]

A local leader reported seeing two bodies with gunshot wounds in the aftermath. Police denied that anyone had been killed.[216] Doctors reported two dead.[217] The local district medical officer said he had been forced to abandon the local hospital because of the rioting.[216]

Effects

Travel restrictions

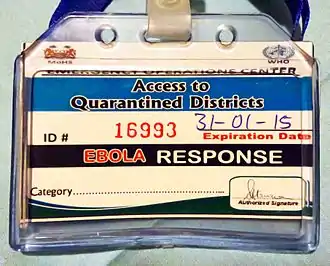

.jpg.webp)

There are various restrictions and quarantines within Sierra Leone, and a state of emergency was declared on 31 July 2014.[218] Countries at higher risk for Ebola in Africa include Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, and Senegal.

- In April 2014, The Gambia banned air travel from several West African countries including Sierra Leone.[219]

- By 11 June 2014, Sierra Leone closed its border with Liberia and Guinea.[28]

- In July airlines of Nigeria and Togo cancelled flights to Freetown.[218]

- On 1 August 2014, Ghana banned air travel from several Ebola impacted countries including Sierra Leone.[220]

- On 8 August 2014, Zambia banned travelers from Sierra Leone and Ebola-affected countries and also banned Zambians from going to those places.[221]

- On 10 August 2014, Mauritania blocked entry of citizens of Sierra Leone.[222]

- On 11 August 2014, Ivory Coast blocked travel from Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea.[223] The restriction was lifted on 26 September 2014.[224]

- On 12 August 2014, Botswana banned travel of all non-Botswanans from Sierra Leone, Guinea, Liberia, and Nigeria; they also added the D.R. Congo later that month.[141]

- On 18 August 2014, Cameroon banned travelers from several countries including Sierra Leone.[141]

- On 21 August 2014, South Africa banned travelers from Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea, but its own citizens were allowed to return from these places.[225]

- On 22 August 2014, a Kenyan airline put temporary restrictions Sierra Leone, saying the Ebola outbreak was underestimated.[226]

- On 22 August 2014, Senegal blocked air travel to Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea.[227]

- On 22 August 2014, Rwanda banned travelers who had been to Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Liberia in the previous 22 days.[141]

- On 11 September 2014, Namibia banned travelers from 'Ebola affected countries'.[141]

- In September 2014, bans on the Sierra Leone hosting federation football (soccer) games continued.[228]

- In October 2014, Trinidad and Tobago banned travelers from the Ebola-stricken West African countries, including Sierra Leone.[229]

- In October 2014, Jamaica, Colombia, Guyana and Saint Lucia banned travelers from Sierra Leone and other affected West African countries.[230]

- In mid October 2014, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines banned Sierra Leone nationals and those from some other West African nations.[231]

- In late October 2014, Panama banned anyone coming from, or had been in Sierra Leone, Liberia, or Guinea in the previous 21 days.[232]

- On 18 October 2014, Belize banned travelers from Sierra Leone, and also banned those that had been there or Guinea or Liberia in the previous 21 days.[141]

- Suriname banned travelers who had been to Sierra Leone, Guinea, or Liberia in the previous 21 days unless they have a health certificate.[141]

- By 21 October 2014, the Dominican Republic banned foreigners who had been to Sierra Leone or other Ebola-affected nations in the previous 30 days.[233]

- On 11 November 2014, The Gambia opened its borders again to travelers from Sierra Leone, Liberia, Nigeria and Guinea.[141]

Additional effects

.jpg.webp)

The outbreak was noted for increasing hand washing stations, and reducing the prevalence of physical greetings such as hand-shakes between members of society.[234]

In June 2014 all schools were closed because of the spread of Ebola.[235]

In August 2014 the S.L. Health Minister was removed from that office.[236] (see Cabinet of Sierra Leone) In October 2014 the Defense Minister was placed in charge of the anti-Ebola efforts.[237] The president at this time was Ernest Bai Koroma.[237]

On 13 October, the UN's International Fund for Agricultural Development stated up to 40% of farms had been abandoned in the worst Ebola-hit areas of Sierra Leone.[238]

In October 2014 Sierra Leone launched a school by radio program, that will be transmitted on 41 of the local radio stations as well as on the only local TV station.[239] (See Cultural effects of the Ebola crisis)

September through October is the malaria season, which may complicate efforts to treat Ebola.[240] For example, one Freetown doctor did not immediately quarantine herself because she thought she had malaria not Ebola.[41] The doctor was eventually diagnosed with Ebola and died in September 2014.[41]

Local works derived from the Ebola crisis

- A Sierra Leone DJ, Amara Bangura, shares knowledge about Ebola in his weekly show which is transmitted on 35 stations in Sierra Leone. He takes selected questions from the text messages sent in and gets answers from health experts and government officials.[241]

- "White Ebola", a political song by Mr. Monrovia, AG Da Profit and Daddy Cool, centered on the general mistrust of foreigners.[242]

- "Ebola in Town", a dance tune by a group of West African rappers, D-12, Shadow and Kuzzy Of 2 Kings warns people of the dangers of the Ebola virus and explaining how to react, became popular in Guinea and Liberia during the first quarter of 2014.[243][244] A dance was developed in which no body contact was required, a rare occurrence in African dance.[245] Some health care workers from the IFRC had concerns that the Ebola In Town song's warning "don't touch your friend" may worsen the stigma.[245][246]

- In August 2014, George Weah and Ghanaian musician Sidney produced a song to raise awareness about Ebola.[247] All proceeds from the track been donated to the Liberian Health Ministry.[248]

- There are a number of Ebola-themed jokes circulating in West Africa to spread awareness.[249]

See also

References

- ↑ "Ebola Situation Report – 28 October 2015" (PDF). World Health Organisation. 28 October 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ↑ WHO Ebola Response Team; Aylward, B; Barboza, P; Bawo, L; Bertherat, E; Bilivogui, P; Blake, I; Brennan, R; Briand, S; Chakauya, J. M; Chitala, K; Conteh, R. M; Cori, A; Croisier, A; Dangou, J. M; Diallo, B; Donnelly, C. A; Dye, C; Eckmanns, T; Ferguson, N. M; Formenty, P; Fuhrer, C; Fukuda, K; Garske, T; Gasasira, A; Gbanyan, S; Graaff, P; Heleze, E; Jambai, A; et al. (2014). "Ebola Virus Disease in West Africa — the First 9 Months of the Epidemic and Forward Projections". New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (16): 1481–1495. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1411100. PMC 4235004. PMID 25244186.

- 1 2 3 4 "Sierra Leone samples: Ebola evidence in West Africa in 2006". EurekAlert!. 14 July 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ Davies, Glyn; Schulte-Herbrüggen, Björn; Kümpel, Noëlle F; Mendelson, Samantha (2008). "Hunting and Trapping in Gola Forests, South-Eastern Sierra Leone: Bushmeat from Farm, Fallow and Forest". Bushmeat and Livelihoods: Wildlife Management and Poverty Reduction. pp. 15–31. doi:10.1002/9780470692592.ch1. ISBN 9780470692592.

- 1 2 "Bat soup blamed as deadly Ebola virus spreads". CBS News. 27 March 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ Kobinger, Gary P.; Leung, Anders; Neufeld, James; Richardson, Jason S.; Falzarano, Darryl; Smith, Greg; Tierney, Kevin; Patel, Ami; Weingartl, Hana M. (2011). "Replication, Pathogenicity, Shedding, and Transmission of Zaire ebolavirus in Pigs". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. pp. 200–208. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir077. PMID 21571728. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Pathogen Safety Data Sheet – Infectious Substances". 17 September 2001. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ Bausch, DG; Towner, JS; Dowell, SF; Kaducu, F; Lukwiya, M; Sanchez, A; Nichol, ST; Ksiazek, TG; Rollin, PE (November 2007). "Assessment of the Risk of Ebola Virus Transmission from Bodily Fluids and Fomites". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 196: S142–S147. doi:10.1086/520545. PMID 17940942.

- ↑ "Can You Get Ebola from Sex?". LiveScience.com. 6 August 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ Daniel G. Bausch. "Assessment of the Risk of Ebola Virus Transmission from Bodily Fluids and Fomites". Archived from the original on 3 July 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Ebola Toll In West Africa Is Likely Hugely Underestimated". The Huffington Post. 3 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Some people would rather die of Ebola than stop hugging sick loved ones". Los Angeles Daily News. 13 October 2014.

- ↑ "Outbreaks Chronology: Ebola Virus Disease". 17 July 2019.

- 1 2 3 "WHO | Sierra Leone: a traditional healer and a funeral". WHO. Archived from the original on 25 September 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola and bushmeat in Africa: Q&A with leading researcher". CIFOR Forests News Blog. 2 September 2014.

- ↑ Hogenboom, Melissa (19 October 2014). "Ebola: Is bushmeat behind the outbreak?".

- ↑ Natasha Lewer (20 October 2014). "I volunteered to fight Ebola in Sierra Leone with MSF. Here's what happened". the Guardian.

- ↑ "Ebola: Liberia confirms cases, Senegal shuts border". BBC News. 31 March 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone News: "No Ebola Virus in Sierra Leone" Health Minister assures". Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Did West Africa's Ebola Outbreak of 2014 Have a Lab Origin?". Independent Science News. 25 October 2022.

- ↑ Maggie Fox (28 July 2014). "Two Americans Stricken With Deadly Ebola Virus in Liberia". NBC News. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

- ↑ "Five dead as Sierra Leone records first Ebola outbreak". Reuters. 26 May 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola expands in Guinea, sickens more in Sierra Leone". CIDRAP. 28 May 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola cases in Sierra Leone triple, to 50". CIDRAP. 30 May 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone ebola death toll 'doubles to 12 in a week'". 9 June 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ Bausch, Daniel G.; Bangura, James; Garry, Robert F.; Goba, Augustine; Grant, Donald S.; Jacquerioz, Frederique A.; McLellan, Susan L.; Jalloh, Simbirie; Moses, Lina M.; Schieffelin, John S. (November 2014). "A tribute to Sheik Humarr Khan and all the healthcare workers in West Africa who have sacrificed in the fight against Ebola virus disease: Mae we hush". Antiviral Research. 111: 33–35. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.09.001. PMID 25196533.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone Declares Emergency as Ebola Spreads". VOA. 12 June 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Sierra Leone shuts borders, closes schools to fight Ebola". Reuters. 11 June 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ Katrina Manson; James Knight (2009). Sierra Leone. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 275.

- ↑ "Ebola crisis: Guinea closes borders with Sierra Leone and Liberia". theguardian.com. 9 August 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola Frontline: Flooding in Sierra Leone Exacerbates Public Health Fears". Newsweek. 11 August 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- 1 2 Gbandia, Silas (12 July 2014). "Ebola Spreads to Sierra Leone Capital of Freetown as Deaths Rise". Bloomberg. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "First Ebola victim in Sierra Leone capital". Yahoo News. 27 July 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone 'hero' doctor's death exposes slow Ebola response". Fox News. 25 August 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone, Liberia deploy troops for Ebola = News 24". 4 August 2014.

- ↑ Ofeibea Quist-Arcton (6 August 2014). "Skeptics In Sierra Leone Doubt Ebola Virus Exists". WVXU.

- ↑ "Two year jail terms for hiding Ebola victims in Sierra Leone". IBNLIVE. 22 August 2014. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone cancels all soccer matches over Ebola outbreak". NY Daily News. New York. 5 August 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- 1 2 "President Koroma must realise right away that Ebola is no Playcook Business!!". Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Ebola ravages health care in Freetown". News24. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Sierra Leone News : How Ebola Killed a popular Freetown female doctor, Dr. Olivette Buck". Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone Demographics Profile 2014". Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Sierra Leone Ebola Burial Teams Struggle as Bodies Decompose". Businessweek.com. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Ebola Response Roadmap Situation Report" (PDF). World Health Organisation. p. 6. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola threatens to destroy Sierra Leone and Liberia". DW.DE. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Expert: 5 Million People Could Die From Ebola Outbreak". Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone launches three-day, door-to-door Ebola prevention campaign". UNICEF. Archived from the original on 7 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ↑ "Inside Sierra Leone's campaign to stop Ebola". UNICEF Connect – UNICEF BLOG. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone to Start 3-Day Nationwide Lockdown to Stop Ebola". ABC News. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola virus shutdown in Sierra Leone yields 'massive awareness'". CBC News. 22 September 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone Ebola burial team attacked despite lockdown". Independent.ie. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone cordons off 3 areas to control Ebola". The Washington Post. 25 September 2014. Archived from the original on 25 September 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ "Third of Sierra Leone population now under quarantine over ebola". Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone News : Africell Presents Second Consignment of Food to all Quarantined Homes". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "A Primer on the Deadly Math of Ebola". Bloomberg.com. 26 September 2014. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola Epidemic Worsening, Sierra Leone Expands Quarantine Restrictions". The New York Times. 26 September 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- 1 2 Nossiter, Adam (5 October 2014). "Ebola Help for Sierra Leone Delayed on the Docks". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Matthew Weaver (2 October 2014). "Ebola infecting five new people every hour in Sierra Leone, figures show". the Guardian. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola: The Tolling Bell". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone records 121 Ebola deaths in a single day". Reuters. 6 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone burial crews reportedly on strike, leaving Ebola victims in the street". Fox News. 8 October 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "British military to provide support in Ebola hit Sierra Leone". Reuters. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ↑ Lisa O'Carroll (3 October 2014). "Ebola: Sierra Leone hospitals running out of basic supplies, say doctors". the Guardian. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola spreading fast in Sierra Leone, warns Save the Children". BBC News. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ↑ "2014 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa". Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone: Ebola and Sierra Leone – Health Care At Breaking Point". allAfrica.com. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- 1 2 "New type of clinic eyed to help stop Ebola". 2 October 2014. Archived from the original on 4 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola Aid Not Stemming Sky-High Infection Rates". 3 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ↑ Anderson, Jon Lee (4 November 2014). "Cuba's Ebola Diplomacy". The New Yorker. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- ↑ "5 People Are Infected With Ebola Every Hour In Sierra Leone". The Huffington Post. 2 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola outbreak: Canada sends 2nd mobile lab to Sierra Leone". CBC News. 4 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Visitors tell of Ebola struggles in Sierra Leone". Philly.com. 5 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone officials struggle to recover bodies of Ebola victims". euronews. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Jack Linshi. "Ebola Healthcare Workers Are Dying Faster Than Their Patients". Time. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Spread of Ebola: What happens when health systems can't cope". The New Zealand Herald. 4 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Canada sends military transport to deliver equipment to Ebola zone". CTVNews. 7 October 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone's burial teams for Ebola victims strike over hazard pay". Reuters. 7 October 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola epidemic in West Africa - Charter Activations - International Disasters Charter". Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "/world-africa-29577175". BBC News. 10 October 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone peacekeepers quarantined over Ebola". News24. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola cases appear in last untouched district in Sierra Leone". Fox News. 16 October 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2014.

- ↑ "Inside RFA Argus – the British ship on course to battle Ebola". Telegraph.co.uk. London. 15 October 2014. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola cases rise sharply in western Sierra Leone". News24.

- ↑ "Ebola Increases Threat to Sierra Leone Pregnancies". VOA. 22 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ Kibadi Mupapa (1999). "Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever and Pregnancy". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 179 (Suppl 1): S11-2. doi:10.1086/514289. PMID 9988157.

- ↑ "2 die in Sierra Leone riot sparked by Ebola tests". News24. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ "Number of Ebola cases nears 10,000". Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "The Royal Navy's ship RFA Argus arrives in Sierra Leone". BBC News. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ↑ Krol, Charlotte (30 October 2014). "Watch: RFA Argus arrives in Sierra Leone to aid fight against Ebola". Telegraph.co.uk. London. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ↑ "RFA Argus arrives in Africa to start "total war" on Ebola". West Briton. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ↑ "2014 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa – Outbreak Distribution Map". CDC. 31 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone News: Bo loses an Ebola Ambulance Driver". Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ↑ Freeman, Colin (1 November 2014). "UK to build three new Ebola labs in Sierra Leone". Telegraph.co.uk. London. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ↑ Sarah DiLorenzoAssociated Press (4 November 2014). "Thousands in Sierra Leone break Ebola quarantine". Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ↑ "The Ebola Outbreak Is Getting Worse in Sierra Leone". VICE News. 6 November 2014. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone News: Marie Stopes opens Ebola Call Centers " Awoko Newspaper". awoko.org. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ Sylvia Blyden. "Sierra Leone Health Ministry Answers Citizens Ebola Questions: Sierra Leone News". news.sl. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ↑ "BBC News – Ebola crisis: Sierra Leone health workers strike". BBC News. 12 November 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ "Marines' Ebola relief arrives in Sierra Leone". NL Times. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone News: Neini Chiefdom isolated". Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- 1 2 "Ebola Spreading Intensely In Sierra Leone As Death Toll Rises: WHO". The Huffington Post. 19 November 2014. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ↑ "British-built Ebola hospital in Sierra Leone only partly operational". Guardian. 20 November 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola response roadmap – Situation report". WHO. 12 November 2014. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ↑ "Cuban doctor in Sierra Leone tests positive for Ebola". The Daily Telegraph. London. 21 November 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ Gladstone, Rick (26 November 2014). "Sierra Leone to Eclipse Liberia in Ebola Cases". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Canada to deploy military health staff to Sierra Leone in Ebola fight". Reuters. 27 November 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone president cancels 3-day business shutdown". News24. Retrieved 30 November 2014.

- ↑ "History". New Democratic Coalition. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ↑ ABC News. "Sierra Leone Seeing 80–100 New Ebola Cases Daily". ABC News. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone threatens to jail families in Ebola crackdown". aljazeera.com. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- ↑ "CAF deploys medical team to Ebola-stricken Sierra Leone". CTVNews. 6 December 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone Doctors Strike for Better Ebola Care". ABC News. 8 December 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone Area to Hold 2-Week Ebola 'Lockdown'". AB News. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola crisis: Sierra Leone hit by largely hidden outbreak; WHO says scores of bodies piled up". ABC News. 10 December 2014. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- ↑ "BBC News – Ebola crisis: Sierra Leone bans Christmas celebrations". BBC News. 12 December 2014. Retrieved 13 December 2014.

- ↑ Shalailah Medhora (14 December 2014). "Ebola: Australian-run centre in Sierra Leone opens for business". the Guardian. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone: MSF distribute 1.5m malaria drugs as part of Ebola response". Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola Virus Disease – Situation Report (Sit-Rep) –) 18 December, 2014" (PDF). 18 December 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone: Ebola Outbreak Updates — December 15, 2014" (PDF). 15 December 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone Puts North On Lockdown Amid Ebola Spread". NPR. 24 December 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ↑ "Situation summary Data published 29 December 2014". World Health organization. 26 December 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone: Ebola Outbreak Updates — December 28, 2014" (PDF). 29 December 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 December 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ↑ Severin Carrell; Libby Brooks; Lisa O'Carroll (29 December 2014). "Ebola case confirmed in Glasgow". The Guardian.

- ↑ Mendick, Robert (30 December 2014). "Hero nurse Pauline Cafferkey could have contracted deadly Ebola at Christmas Day service". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ↑ "New Ebola lockdown in Sierra Leone as airport checks upped". Yahoo News. 4 January 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ "Ebola Situation report on 7 January 2015" (PDF). World Health organization. 7 January 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ↑ "Ebola: MSF opens new treatment centre in Kissy, Sierra Leone". Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors without Borders.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone: Ebola Virus Disease – Situation Report (Sit-Rep) 10 January 2015" (PDF). 10 January 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ↑ "Seoul set to send 2nd medical team to Ebola-hit Sierra Leone". Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone declares first Ebola-free district". The Guardian. 10 January 2015. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- ↑ "Brit flown back to UK after exposure to Ebola". scotsman.com. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ↑ Zoroya, Gregg (5 February 2015). "Downward Ebola trend suddenly reverses itself". USA Today. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ↑ "Ebola-hit Sierra Leone to Reopen Schools March 30". VOA. 5 February 2015. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ↑ "Decline in Ebola cases flattens, raising UN concern". philstar.com. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- ↑ "More Ebola in Guinea, Sierra Leone last week, no Liberia cases says WHO". gnnliberia.com. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 7 March 2015.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone plans another shutdown to stop Ebola's spread – US News". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ↑ "BBC News – Ebola crisis: Sierra Leone lockdown to hit 2.5m people". BBC News. 19 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ↑ Mundasad, Smitha (23 March 2015). "Ebola outbreak 'over by August', UN suggests". BBC News. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone Ebola lockdown exposes hundreds of suspected cases". Fox News. 31 March 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ↑ Maggie Fox (13 May 2015). "Ebola Epidemic Slows Even More, World Health Organization Says". NBC News. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Ebola". internationalsos.com. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ Alexandra Sifferlin (17 August 2015). "Sierra Leone Has First Week of No New Ebola Cases". Time. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

- ↑ Sierra Leone begins 42-day countdown to be declared free of Ebola virus transmission. UN News Center. 26 August 2015.

- ↑ "New Ebola death in Sierra Leone sets back efforts to beat epidemic". News 24. 1 September 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- ↑ "New Ebola case in Sierra Leone quarantine village: president". Yahoo News. 7 September 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone officials confirm 3 new cases of Ebola among high risk contacts with fatal case". Associated Press. 8 September 2015. Retrieved 9 September 2015.

- ↑ "New Ebola death reported in northern Sierra Leone". CTV News. 14 September 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ↑ "Hundreds quarantined as Ebola returns to north Sierra Leone district". Reuters. 14 September 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ↑ "Sex and masturbation may hamper Ebola eradication efforts". Reuters. 9 September 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2015.

- ↑ "Ebola Situation Report - 11 November 2015". Archived from the original on 11 November 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ↑ "Ebola Situation Report – 9 December 2015". Archived from the original on 11 December 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ↑ "Ebola virus: New case emerges in Sierra Leone". BBC News. 15 January 2016.

- ↑ "WHO – Latest Ebola outbreak over in Liberia; West Africa is at zero, but new flare-ups are likely to occur". World Health Organization.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone puts more than 100 people in quarantine after new Ebola death". the Guardian. 17 January 2016.

- ↑ "Government Press Statement: Confirmation of EVD Death in Sierra Leone – 16 January 2016". WHO. 16 January 2016. Archived from the original on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone confirms second case of Ebola in a week". Yahoo News. 20 January 2016. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ↑ "Ebola Situation Report - 16 March 2016 - Ebola". Archived from the original on 18 March 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ Anderson, E.L.; Beresford, A (2016). "Infectious injustice: the political foundations of the Ebola crisis in Sierra Leone" (PDF). Third World Quarterly. 37 (3): 468–486. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1103175. S2CID 73696543.

- ↑ "BBC News – Ebola drains already weak West African health systems". BBC News. 24 September 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- 1 2 "WHO pulls staff after worker infected with Ebola in Sierra Leone". Reuters. 26 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola Patient Arrives in Germany for Treatment". NBC News. 27 August 2014. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- 1 2 "German hospital: Scientist treated for Ebola cured". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "'Collateral' death toll expected to soar in Africa's Ebola crisis". Reuters. 26 September 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Mabesseneh Hospital up against Ebola". Archived from the original on 31 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ "US official warns Ebola outbreak will get worse". The Big Story. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola-infected doctor in Sierra Leone, Sahr Rogers, dies". CBC News. 27 August 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone requests funds for Ebola evacuation". OUDaily.com. 15 September 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "WHO revises up number of health workers killed by Ebola in Sierra Leone". Fox News. 23 September 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone: Ebola Virus Disease – Situation Report (Sit-Rep) – 25 October 2014" (PDF). 24 October 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- ↑ "Fifth doctor in Sierra Leone dies of Ebola". MSNBC. 3 November 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- 1 2 "Doctor with Ebola dies at Nebraska hospital". News24. 17 November 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ "Update 1-Seventh Sierra Leone doctor killed by Ebola -source". Reuters. 18 November 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ "8th Doctor Infected with Ebola in Sierra Leone; Burial Workers Dump Corpses in Protest over Pay". Democracy Now!. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ ABC News. "Health News & Articles – Healthy Living – ABC News". ABC News. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- 1 2 ABC News. "Sierra Leone Official: Ebola May Have Reached Peak". ABC News. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ Sieff, Kevin (27 November 2014). "Sierra Leone physician who treated doctor with Maryland ties is diagnosed with Ebola". The Washington Post. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ↑ "Two Sierra Leone doctors die of Ebola". SABC. 6 December 2014. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ↑ "2 Sierra Leone doctors die of Ebola in 1 day". Reuters. 6 December 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ↑ "11th Sierra Leonean Doctor Dies From Ebola". ABC News. 18 December 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- ↑ "British Ebola patient arrives in UK for hospital treatment". BBC News. 24 August 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola:British nurse makes 'full recovery' and leaves hospital". he Week. 3 September 2014. Archived from the original on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ↑ Lisa O'Carroll (19 October 2014). "Will Pooley told he may not be immune to Ebola as he returns to Sierra Leone". the Guardian.

- ↑ "Spain to Repatriate Priest Diagnosed with Ebola in Sierra Leone". Newsweek. 21 September 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Second Spanish priest with Ebola dies in Madrid". San Antonio Express-News. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Nurse 'infected with Ebola' in Spain". BBC News. 6 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Spanish nurse tests negative for Ebola after treatment". DW.DE. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ "Third Doctor Dies From Ebola in Sierra Leone". Time. Archived from the original on 23 September 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Bite sends Ebola virus doctor to Geneva". Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- 1 2 Davenport, Christian (27 September 2014). "NIH expected to admit American patient exposed to Ebola virus". The Washington Post. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "NIH discharges patient who was exposed to Ebola". Southern Maryland Newspapers Online - SoMdNews.com. Archived from the original on 23 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola patient arrives in Germany from Sierra Leone". Fox News. 3 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ugandan doctor with Ebola named". Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ "Norwegian woman infected with Ebola". VG. 6 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola virus victim arrives in Norway by special jet". Norway. 6 October 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "The Ebola Infected women will not get ZMapp". Norway. 8 October 2014. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola Infected woman gets last dose of medicine in the world". World News (WN) Network. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "How It Feels to Have Ebola: 'It's Like Your Body Doesn't Belong to You Anymore'". Newsweek. 6 October 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "UK Ebola patient gets experimental drug". BBC News, Health. 26 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ↑ Dassanayake, Dion (1 September 2014). "First British Ebola victim recovering 'pretty well' after being given experimental drug". Express. UK. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ "Spanish missionary doctor infected with Ebola dies". USA Today. 12 August 2014.

- ↑ Stewart, Connie (3 August 2014). "Ebola patient got experimental serum, missionary group says". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "American doctor treated for Ebola released from hospital". Reuters. 21 August 2014.

- ↑ "Can you really recover from Ebola?". The Daily Telegraph. London. 22 August 2014.

- ↑ "UN Ebola victim being treated in French hospital". Telegraph.co.uk. London. 2 November 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ↑ "Dr. Martin Salia Battling Between Life and Death at the Hastings Holding Centre". Cocorioko International Newspaper. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ↑ ABC News. "Ebola in America: US Doctor Contracts Ebola in Sierra Leone, Will be Flown to Nebraska for Treatment – ABC News". ABC News. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola-infected doctor 'extremely critical' in US". News24. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ "Cuban doctor in Sierra Leone tests positive for Ebola". News24. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ "WHO – Cuban medical team heading for Sierra Leone". Archived from the original on 14 September 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Ebola Help for Sierra Leone Is Nearby, but Delayed on the Docks", The New York Times, Adam Nossiter, 5 October 2014.

- ↑ Mackey, Robert (6 November 2014). "Sierra Leone Detains Journalist for Criticism of Ebola Response". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone talk show host released from jail". News24. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ "David Tam Baryoh's forced signed confession to freedom". Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola myths: Sierra Leonean DJ tackles rumours and lies over the airwaves". the Guardian. 9 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- 1 2 "WHO – Spreading the word about Ebola through music". Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Curfew in Sierra Leone town after rioting, shooting over Ebola case". Yahoo News. 21 October 2014. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- 1 2 ""Ebola riot in S. Leone kills two as WHO to launch vaccine trials", Rod Mac Johnson, AFP, October 22, 2014". Yahoo News. 22 October 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- 1 2 "Sierra Leone declares state of emergency as Ebola spreads". The Irish Times. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Gambia bans flights from Ebola-hit countries". Business Day Live. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ghana Bans Flights From Nigeria, Sierra Leone, And Liberia Over Ebola Concerns". Sahara Reporters. August 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Zambia bans travellers from countries hit by Ebola". News24. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ "Mauritania bans entry of citizens from Ebola-hit states". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola outbreak: Ivory Coast bans flight from three states". BBC News. 11 August 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ivory Coast lifts travel restrictions on Ebola-stricken countries". Macleans.ca. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola: South Africa bans travellers from Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone". Premium Times. 21 August 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola: airlines cancel more flights to affected countries". the Guardian. 22 August 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Senegal blocks Ebola aid flight, imposes travel curbs". Fox News. 22 August 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone Sports: Ebola football ban on West African countries still remain". Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "T&T orders Ebola travel ban". Trinidad Express Newspaper. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ↑ "Jamaica bans travellers who have been to Ebola-affected nations". the Guardian.

- ↑ "St Vincent bans nationals from three West African States due to Ebola". Dominica News Online.

- ↑ Thomson Reuters Foundation. "Panama bars travelers from three Ebola-hit African countries". Retrieved 27 October 2014.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ "Dominican Republic joins entry ban for Ebola-affected countries". Yahoo News. 21 October 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ↑ "Devastating news from the Ebola clinic". BBC News. 6 October 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "Sierra Leone shuts borders, closes schools to fight Ebola". Reuters. 11 June 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "Health minister Miatta Kargbo sacked". 29 August 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Ebola crisis: Sierra Leone revamps response team". BBC News. 18 October 2014.

- ↑ "Operation United Assistance" – Intelligence Summary, 14 October 2014, United States Africa Command, Unclassified report, 14 October 2014, p.2.

- ↑ "Ebola-hit Sierra Leone Launches School by Radio". NDTV.com. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola: How bad can it get?". BBC News. 6 September 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola myths: Sierra Leonean DJ tackles rumours and lies over the airwaves". the Guardian. 9 October 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ↑ "Beats, Rhymes and Ebola". Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ebola virus causes outbreak of infectious dance tune". the Guardian. 27 May 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.