The Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey is an American military tiltrotor aircraft whose history of accidents have provoked concerns about its safety. The aircraft was developed by Bell Helicopter and Boeing Helicopters; the companies work together to manufacture and support the aircraft.

As of November 2023, 16 V-22 Ospreys have been damaged beyond repair in accidents that have killed a total of 62 people. Four crashes killed a total of 30 people during testing from 1991 to 2000.[1] Since the V-22 became operational in 2007, 12 crashes, including two in combat zones,[2][3] and several other accidents and incidents have killed a total of 32 people.[4]

Most crashes have been with the most common of the three variants of the tiltrotor, the MV-22B, procured and flown by the US Marine Corps. A handful of crashes have been with the CV-22B, flown by US Air Force Special Operations Command. No crashes have yet occurred with the newest carrier onboard delivery variant, the CMV-22B, flown by the US Navy.

Crashes and hull–loss accidents

June 1991

On 11 June 1991, a miswired flight control system led to two minor injuries when the left nacelle struck the ground while the aircraft was hovering 15 feet (4.6 m) in the air, causing it to bounce and catch fire at the New Castle County Airport in Delaware.[1][5][6] The pilot, Grady Wilson, suspected that he may have accidentally set the throttle lever the opposite direction to that intended, exacerbating the crash if not causing it.[7]

July 1992

On 20 July 1992, pre-production V-22 #4's right engine failed and caused the aircraft to drop into the Potomac River by Marine Corps Base Quantico with an audience of Department of Defense and industry officials.[8][9][10] Flammable liquids collected in the right nacelle and led to an engine fire and subsequent failure. All seven on board were killed and the V-22 fleet was grounded for 11 months following the accident.[1][11][12] A titanium firewall now protects the composite propshaft.[13]

April 2000

A V-22 loaded with Marines, to simulate a rescue, attempted to land at Marana Northwest Regional Airport in Arizona on 8 April 2000. It descended faster than normal (over 2,000 ft/min or 10 m/s) from an unusually high altitude with a forward speed of under 45 miles per hour (39 kn; 72 km/h) when it suddenly stalled its right rotor at 245 feet (75 m), rolled over, crashed, and exploded, killing all 19 on board.[14][15]

The cause was determined to be vortex ring state (VRS), a fundamental limitation on vertical descent which is common to helicopters. At the time of the mishap, the V-22's flight operations rules restricted the Osprey to a descent rate of 800 feet per minute (4.1 m/s) at airspeeds below 40 knots (74 km/h) (restrictions typical of helicopters); the crew of the accident aircraft had descended at over twice this rate.[16] Another factor that may have triggered VRS was the operation of multiple aircraft in close proximity, also believed to be a risk factor for VRS in helicopters.[1]

Subsequent testing showed that the V-22 and other tiltrotors are generally less susceptible to VRS than helicopters; VRS entry is more easily recognized, recovery is more intuitive for the pilot, altitude loss is significantly less, and, with sufficient altitude (2,000 ft or 610 m or more), VRS recovery is relatively easy. The V-22 has a safe descent envelope as large as or larger than most helicopters, further enhancing its ability to enter and depart hostile landing zones quickly and safely. The project team also dealt with the problem by adding a simultaneous warning light and voice that says "Sink Rate" when the V-22 approaches half of the VRS-vulnerable descent rate.[1]

December 2000

On 11 December 2000, a V-22 had a flight control error and crashed near Jacksonville, North Carolina, killing all four aboard. A vibration-induced chafing from an adjacent wiring bundle caused a leak in the hydraulic line, which fed the primary side of the swashplate actuators to the right side rotor blade controls. The leak caused a Primary Flight Control System (PFCS) alert. A previously-undiscovered error in the aircraft's control software caused it to decelerate in response to each of the pilot's eight attempts to reset the software as a result of the PFCS alert. The uncontrollable aircraft fell 1,600 feet (490 m) and crashed in a forest. The wiring harnesses and hydraulic line routing in the nacelles were subsequently modified. This caused the Marine Corps to ground its fleet of eight V-22s, the second grounding in 2000.[1][17][18]

March 2006

A MV-22B experienced an uncommanded engine acceleration while turning on the ground at Marine Corps Air Station New River, NC. Since the aircraft regulates power turbine speed with blade pitch, the reaction caused the aircraft to go airborne with the Torque Control Lever (TCL, or throttle) at idle. The aircraft rose 6 to 7 feet (1.8 to 2.1 m) into the air (initial estimates suggested 20 to 30 feet) and then fell to the ground, causing damage to its starboard wing; the damage was valued at approximately US$7 million.[19][20] It was later found that a miswired cannon plug to one of the engine's two Full Authority Digital Engine Controls (FADEC) was the cause. The FADEC software was also modified to decrease the time needed for switching between the redundant FADECs to eliminate the possibility of a similar mishap occurring in the future.[21] The aircraft was found to be damaged beyond repair and stricken from Navy's list in July 2009.[22][23]

April 2010

In April 2010, a CV-22 crashed near the city of Qalat in Zabul Province, Afghanistan.[2] Three US service members and one civilian were killed and 16 injured in the crash.[24] Initially, it was unclear if the accident was caused by enemy fire.[25][26] The loaded CV-22B was at its hovering capability limit, landing at night near Qalat (altitude approx. 5,000 feet) in brownout conditions, in turbulence due to the location in a gully.[24][27] The USAF investigation ruled out brownout conditions, enemy fire, and vortex ring state as causes. The investigation found several factors that significantly contributed to the crash: these include low visibility, a poorly-executed approach, loss of situational awareness, and a high descent rate.[28]

Brig. Gen. Donald Harvel, board president of the first investigation into the crash, fingered the "unidentified contrails" during the last 17 seconds of flight as indications of engine troubles.[29] Harvel has become a critic of the aircraft since his retirement and states that his retirement was placed on hold for two years to silence him from speaking publicly about his concerns about the aircraft's safety.[30] The actual causes of the crash may never be known because US military aircraft destroyed the wreckage and black box recorder.[31] Former USAF chief V-22 systems engineer Eric Braganca stated that the V-22's engines normally emit puffs of smoke and the data recorders showed that the engines were operating normally at that time.[32]

April 2012

An MV-22B belonging to 2nd Marine Aircraft Wing, VMM-261 was participating in Exercise African Lion when it crashed near Tan-Tan and Agadir, Morocco, on 11 April 2012, killing two Marines. Two others were seriously injured, and the aircraft was lost.[33][34][35] U.S. investigators found no mechanical flaw with the aircraft,[36] and human error was determined to be the cause.[37]

June 2012

On 13 June 2012, a USAF CV-22B crashed at Eglin Air Force Base in Florida during training. All five aboard were injured;[38] two were released from the hospital shortly after.[39] The aircraft came to rest upside-down and received major damage.[40] The cause of the crash was determined to be pilot error, with the CV-22 flying through the proprotor wash of another aircraft.[41] The USAF restarted formation flight training in response.[42]

May 2015

An MV-22B Osprey participating in a training exercise at Bellows Air Force Station, Oahu, Hawaii, sustained a hard landing which killed two Marines and injured 20.[43] The aircraft sustained fuselage damage and a fire onboard.[44][45] The aircraft was determined to have suffered dust intake to the right engine, leading the Marine Corps to recommend improved air filters, and reduced allowed hover time in dust from 60 to 30 seconds.[46][47]

December 2016

On 13 December 2016 at 10:00 p.m., an MV-22B crashed while landing onto a reef in shallow water 0.6 miles (0.97 km) off the Okinawa coastline of Camp Schwab where the aircraft broke apart. All five crew members aboard with Marine Aircraft Group 36, 1st Marine Aircraft Wing were rescued. Two crew members were injured, and all were transported for treatment. Ospreys in Japan were grounded the following day.[48][49][50] An investigation into the mishap was launched.[51] Preliminary reports indicated that, during in-flight refueling with a HC-130, the refueling hose was struck by the Osprey's rotor blades.[52] On 18 December, after a review of MV-22B safety procedures, the III Marine Expeditionary Force (IIIMEF) announced that it would resume flight operations, concluding that they were confident that the mishap was due "solely to the aircraft's rotor blades coming into contact with the refueling line."[53]

August 2017

An MV-22B Osprey assigned to the 31st Marine Expeditionary Unit, VMM-265, crashed in Shoalwater Bay, Australia on 5 August 2017, killing three Marines. The tiltrotor struck the USS Green Bay and crashed into the sea shortly after taking off from amphibious assault ship USS Bonhomme Richard. 23 personnel were recovered from the stricken aircraft, with three confirmed dead.[54][55][56][57][58]

September 2017

An MV-22B Osprey operating in Syria as part of Operation Inherent Resolve was damaged beyond repair in a hard landing on 28 September 2017.[59] Two people on board the aircraft were injured.[60][61][62] The non–salvageable Osprey burned shortly after the crash.[63]

March 2022

An MV-22B Osprey participating in NATO exercise Cold Response crashed in Gråtådalen, a valley in Beiarn, Norway on 18 March 2022, killing all four Marines onboard.[64][65][66] The crew were confirmed dead shortly after Norwegian authorities discovered the crash site.[67] Investigators concluded that the causal factor of the crash was pilot error due to low altitude steep bank angle maneuvers exceeding the aircraft's normal operating envelope.[68] Investigators noted that an unauthorized personal GoPro video camera was found at the crash site and was in use at the time of the crash. "Such devices are prohibited on grounds that they can incentivize risktaking and serve as a distraction; that may have been the case with Ghost 31," the report reads.[69]

June 2022

An MV-22B Osprey belonging to 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing crashed near Glamis, California, on 8 June 2022, killing all five Marines onboard. Among the fatalities was Captain John J. Sax, son of the former Major League Baseball player and LA Dodger Steve Sax.[70] The accident investigation determined that the crash was caused by a dual hard clutch engagement causing catastrophic malfunction of the aircraft's gearbox that lead to drive system failures.[71] From 2010 to the time of the crash, there had been 16 similar clutch issues on Marine Ospreys.[72] Initial reports erroneously claimed that nuclear material were onboard the aircraft at the time of the crash.[73][74][75]

August 2023

An MV-22B Osprey belonging to 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, VMM-363 crashed on Melville Island, Australia on 27 August 2023, killing three Marines. The accident occurred while the aircraft was participating in "Predators Run 2023", a joint military exercise involving 2,500 personnel from Australia, the United States, Indonesia, the Philippines and Timor-Leste.[76] The aircraft was carrying 23 U.S. Marines,[77] of which three were killed at the crash scene on the large island in the Timor Sea, 60 km north of Darwin, while another five were flown to a hospital in critical condition.[76]

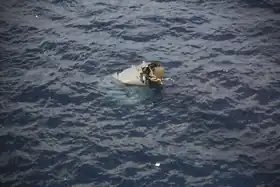

November 2023

A CV-22B Osprey assigned to the US Air Force's 353rd Special Operations Wing crashed into the East China Sea about one kilometer (0.6 mile) off Yakushima Island, Japan, on 29 November 2023, killing all eight airmen aboard. The Osprey, based at Yokota Air Base in Western Tokyo, was flying from Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni in Yamaguchi Prefecture to Kadena Air Base on Okinawa Island in clear weather and light winds. Witnesses reported seeing the aircraft flying inverted with flames engulfing the aircraft's left nacelle before an explosion occurred and the aircraft subsequently crashed in waters east of the island near Yakushima Airport. An Air Force investigation into the cause of the crash is ongoing.[78][79][80][81] Japan grounded its fleet of 14 Ospreys after the crash. The US Air Force grounded all of its CV-22 Ospreys one week later.[82] The US Navy and Marines grounded their fleets of V-22 Ospreys pending the outcome of the CV-22 investigation.[83]

On 3 January 2024 it was announced that the Flight Data and Cockpit Voice Recorders had been located and would be transported to laboratories for data retrieval, a process that would take several weeks. Seven of the eight remains of the airmen had been recovered and publicly identified, but search efforts were still underway for the remains of the eighth.[84]

Other accidents and notable incidents

July 2006

A V-22 experienced compressor stalls in its right engine in the middle of its first transatlantic flight to the United Kingdom for the Royal International Air Tattoo and Farnborough Airshow on 11 July 2006.[85] It had to be diverted to Iceland for maintenance. A week later it was announced that other V-22s had been having compressor surges and stalls, and the Navy launched an investigation into it.[86]

December 2006

It was reported that a serious nacelle fire occurred on a Marine MV-22 at New River in December 2006.[87][88]

March 2007

A V-22 experienced a hydraulic leak that led to an engine-compartment fire before takeoff on 29 March 2007.[87]

November 2007

An MV-22 Osprey of VMMT-204 caught on fire during a training mission and was forced to make an emergency landing at Camp Lejeune on 6 November 2007. The fire, which started in one of the engine nacelles, caused significant aircraft damage, but no injuries.[89]

After an investigation, it was determined that a design flaw with the engine air particle separator (EAPS) caused it to jam in flight, causing a shock wave in the hydraulics system and subsequent leaks. Hydraulic fluid leaked into the IR suppressors and was the cause of the nacelle fires. As a result, all Block A V-22 aircraft were placed under flight restrictions until modification kits could be installed. No fielded Marine MV-22s were affected, as those Block B aircraft already incorporated the modification.[90]

2009

An Air Force CV-22 suffered a Class A mishap with more than $1 million in damage during FY 2009. No details were released.[91]

July 2011

On 7 July 2011, an MV-22 crew chief from VMM-264 squadron fell nearly 200 ft to his death in southwestern Afghanistan.[92]

October 2014

In early October 2014, an MV-22 Osprey lost power shortly after takeoff from the USS Makin Island. The aircraft splashed down in the Arabian Sea and was briefly partially submerged four feet (one metre) before the pilots regained control and landed on the carrier deck. One marine drowned after his life preserver failed to inflate when he bailed out of the aircraft. The accident was attributed to the aircraft being accidentally started in maintenance mode, which reduces engine power by a fifth.[93]

January 2017

On 29 January 2017, an MV-22 experienced a hard landing during the Yakla raid in Al Bayda, Yemen against Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula militants, causing two injuries to U.S. troops. The aircraft could not fly afterward and was destroyed by U.S. airstrikes.[94][95][3]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Saving the Pentagon's Killer Chopper-Plane". Wired. July 2005.

- 1 2 "CV-22 Osprey Crashes in Afghanistan". ISAF_NATO. 9 April 2010. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013.

- 1 2 Raid in Yemen: Risky From the Start and Costly in the End, The New York Times, Eric Schmitt & David Sanger, 1 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ↑ "Bell Boeing MV-22 Osprey accidents and incidents" Aviation Safety Network Database

- ↑ "Osprey crashes on its maiden flight". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). (news services). 12 June 1991. p. 3A.

- ↑ "Osprey tests halted". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. (wire dispatches). 13 June 1991. p. 2.

- ↑ Whittle 2010, pp. 200–202.

- ↑ "Seven killed when Osprey crashes". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). (Washington Post). 21 July 1992. p. A4.

- ↑ Drinkard, Jim (21 July 1992). "Second V-22 crash may affect funding". Moscow-Pullman Daily News. (Idaho-Washington). Associated Press. p. 6A.

- ↑ "7 missing as Osprey crashes". Toledo Blade. (Ohio). (staff and wire reports). 21 July 1992. p. 3.

- ↑ "V-22 Osprey crash kills 7 Aircraft second of 5 prototypes to go down." Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 21 July 1992.

- ↑ Norton 2004, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Whittle 2010, p. 246.

- ↑ Gross, Kevin, Lieutenant Colonel U.S. Marine Corps; Tom Macdonald, MV-22 test pilot; Ray Dagenhart, MV-22 lead government engineer (September 2004). "Dispelling the Myth of the MV-22". Proceedings. The Naval Institute (September 2004). Retrieved 9 April 2009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Cox, Bob. "V-22 Pilots Not To Blame For Crash, Widows Say", Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 4 June 2011.

- ↑ Norton 2004, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Dao, James. "After North Carolina Crash, Marines Ground Osprey Program." New York Times, 13 December 2000.

- ↑ "Marine V-22 Ospreys cleared to soar again." Spokesman-Review, 6 September 2000.

- ↑ "V22 Osprey's 3.2 second accident Flight". iasa.com.au, accessed 14 October 2013.

- ↑ "Osprey Down: Marines Shift Story on Controversial Warplane's Safety Record". Condé Nast, 13 October 2011.

- ↑ White, Lance Cpl. Samuel D. (2006). "VMM-263 ready to write next chapter in Osprey program". Marine Corps News. United States Marine Corps. Archived from the original on 26 June 2006. Retrieved 10 April 2006.

- ↑ Bell-Boeing MV-22B Osprey 27-MAR-2006. Aviation Safety Network

- ↑ Bell MV-22B Osprey c/n D0056. Helis.com

- 1 2 "The high cost of building a new flying machine". Charlotte Observer. 2 May 2010.

- ↑ "ISAF: 4 killed in U.S. aircraft crash in Afghanistan". CNN. 9 April 2010.

- ↑ Hodge, Nathan (9 April 2010). "Controversial Spec-Ops Tiltrotor Crashes in Afghanistan". Wired.

- ↑ McIntyre, Jamie. "CV-22 Lost Due to Pilot Error". dodbuzz.com, 18 May 2010.

- ↑ "CV-22B Accident Investigation Board" Archived 6 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, "CV-22 Accident Investigation Board Results Released" Archived 25 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Air Force, 16 December 2010.

- ↑ Rolfsen, Bruce. "Generals clash on cause of April Osprey crash." Airforce Times, 22 January 2011.

- ↑ Axe, David. "General: 'My Career Was Done' When I Criticized Flawed Warplane" Archived 26 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Wired, 4 October 2012

- ↑ Thompson, Mark. "So Why Did That V-22 Crash?" Archived 20 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Time. 18 December 2010.

- ↑ Axe, David. "Air Force Engineer Takes on General Over Controversial Warplane Crash." Wired Magazine, 15 October 2012.

- ↑ Majumdar, Dave. "Two killed in USMC MV-22 accident in Morocco." Flight International, 11 April 2012. Retrieved: 13 April 2012.

- ↑ "Two U.S. Marines killed in Morocco helicopter crash" Archived 15 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine. BNO News, 12 April 2012. Retrieved: 16 April 2012.

- ↑ "ASN Wikibase Occurrence # 144945" Aviation Safety Network, 15 April 2012. Retrieved: 16 April 2012.

- ↑ "MV-22 Osprey that crashed in Morocco was mechanically perfect" Yomiuri Shimbun, 9 June 2012. Retrieved: 15 June 2012.

- ↑ Whittle, Richard. "Marines Peg 'Bad Flying' As Cause of April V-22 Crash in Morocco" Archived 13 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine. AOL Defense, 9 July 2012. Retrieved: 10 July 2012.

- ↑ "5 airmen injured when Air Force Osprey crashes during training mission in Florida Panhandle". Washington Post. Associated Press. 14 June 2012. Archived from the original on 16 January 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ↑ "Two airmen injured in Osprey crash released from hospital". Northwest Florida Daily News, 15 June 2012. Retrieved: 16 June 2012.

- ↑ "5 airmen hurt in Osprey crash near Navarre". Pensacola News Journal, 14 June 2012. Retrieved: 16 June 2012.

- ↑ "AFSOC Crash Report Faults Understanding Of Osprey Rotor Wake". Breaking Defense.

- ↑ "Crash Drives Air Force to Restart CV-22 Pilot Formation Training: EXCLUSIVE". Breaking Defense. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012.

- ↑ McGarry, Brendan. "Billows of Dust, a Sudden 'Pop' and an Osprey Falls from the Sky". Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ "1 killed, several injured in Osprey crash at Bellows Air Force Station". hawaiinewsnow.com. HawaiiNewsNow. 17 May 2015. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ↑ "2nd Marine dies of injuries suffered in military plane crash". ap.org. Associated Press. 20 May 2015. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ Fatal MV-22 crash in Hawaii linked to excessive debris ingestion 25 November 2015

- ↑ Whittle, Richard. "Fatal Crash Prompts Marines To Change Osprey Flight Rules" Breaking Defense, 16 July 2015.

- ↑ Butterfield, Joseph, 1st Lt. "Okinawa Area Coordinator addresses the media about MV-22 incident" Archived 22 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. III Marine Expeditionary Force, United States Marine Corps, 14 December 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ↑ McCurry, Justin. "US grounds Osprey fleet in Japan after aircraft crashes off Okinawa". the Guardian, 14 December 2016. Retrieved: 15 December 2016.

- ↑ オスプレイ墜落:機体折れ、無残 衝撃の大きさ物語る【写真特集】, Okinawa Times, 14 December 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ↑ Butterfield, Joseph, 1st Lt. "Crew Rescued after MV-22 Mishap off Coast of Okinawa" Archived 17 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine. III Marine Expeditionary Force, United States Marine Corps, 13 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ MATTHEW M. BURKE AND CHIYOMI SUMIDA, "Marines ground Ospreys on Okinawa, blame crash on severed hose" STARS AND STRIPES, 13 December 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ↑ Butterfield, Joseph, 1st Lt. "MV-22 Ospreys in Japan continue flight operations" Archived 18 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. III Marine Expeditionary Force, United States Marine Corps, 18 December 2016. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ↑ Ironside, Robyn; Gordon, Krystal; Vujkovic, Melanie (7 August 2017). "Osprey mishap: Second marine identified after US military aircraft crash". ABC News. Australia. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ Schogol, Jeff (5 August 2017). "Three Marines missing after Osprey crashes off Australia". Marine Corps Times. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ "3 U.S. Marines missing after heli-plane crashes off Australian coast". NBC News. 5 August 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ "MV-22 struck flight deck before fatal crash". Flight Global. 10 August 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ↑ "Osprey involved in fatal crash off Australia has been recovered". Stars and Stripes. 6 September 2017.

- ↑ Browne, Ryan (29 September 2017). "US aircraft crashes in Syria". CNN. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ↑ "Two Service Members Injured after V-22 Osprey Suffers 'Hard Landing' in Syria". World Maritime News. 2 October 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ↑ 2 Troops Injured in Non-Combat V-22 Crash in Syria Military.com

- ↑ Bell/Boeing MV22B Osprey 29-SEP-2017. Aviation Safety Network

- ↑ us-marine-corps-v-22-osprey-crash-syria Aviationanalysis

- ↑ II MEF [@iimefmarines] (19 March 2022). "Update: 4 Marines assigned to 2d Marine Aircraft Wing, are listed in Duty Status Whereabouts Unknown following a training incident in support of Exercise Cold Response 2022 on the evening of March 18, 2022. https://t.co/ZzYkQL2ZWS" (Tweet). Retrieved 29 December 2022 – via Twitter.

- ↑ "Amerikansk militærfly har styrtet i Nordland" (in Norwegian). NRK. 18 March 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ↑ "U.S. military plane crashes with four on board in Norway, Norwegian government says". CBS News. 18 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ↑ "4 U.S. troops die in Norway plane crash; unrelated to Ukraine". POLITICO. Associated Press. 19 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ↑ South, Todd (14 August 2022). "Pilot error the cause of Norway Osprey crash that killed 4 Marines". Marine Corps Times. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ↑ Charpentreau, Clement (16 August 2022). "Did a GoPro lead to pilot error in the crash of a USMC MV-22 Osprey in Norway?". Aerotime Hub. Archived from the original on 9 December 2023.

- ↑ "Son of former LA Dodger Steve Sax killed in California Osprey crash". 12 June 2022.

- ↑ Katz, Justin (21 July 2023). "'Unpreventable': Deadly 2022 Osprey caused by malfunction, not crew". Breaking Defense. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ↑ Baldor, Lolita (21 July 2023). "Deadly crash of Marine Osprey last year was caused by mechanical failure, report says". AP News. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ↑ "Five Marines killed in military aircraft crash in California" KESQ

- ↑ Reyes, Jesus (Jun. 8, 2022)."Military plane crashes in Imperial County; No nuclear material aboard aircraft". KESQ

- ↑ "5 Marines killed in California aircraft crash". 9 June 2022.

- 1 2 Parkinson, (A)manda (27 August 2023). "US military aircraft crashes off northern Australia coast during training exercise". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ↑ Mongilio, Heather (27 August 2023). "UPDATED: 3 U.S. Marines Killed in Australian MV-22 Crash". USNI News. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ↑ Yamaguchi, Mari (29 November 2023). "US military Osprey aircraft with 8 aboard crashes into the sea off southern Japan". AP News. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ↑ Altman, Howard (29 November 2023). "CV-22B Osprey Tilt-Rotor Crashes Off Japanese Coast". The War Zone. Retrieved 29 November 2023.

- ↑ "MILPERSMAN 1770-020 DUTY STATUS-WHEREABOUTS UNKNOWN AND "MISSING" STATUS RECOMMENDATIONS" (PDF). United States Navy. 31 October 2023.

- ↑ Yamagucci, Mari (4 December 2023). "Divers have found wreckage, 5 remains from Osprey aircraft that crashed off Japan, US Air Force says". AP News. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ↑ Copp, Tara (7 December 2023). "US military grounds entire fleet of Osprey aircraft following a deadly crash off the coast of Japan". AP News. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ↑ Britzky, Haley (7 December 2023). "US military grounds Osprey fleet after crash off coast of Japan kills 8 US airmen | CNN Politics". CNN. Retrieved 12 December 2023.

- ↑ https://www.military.com/daily-news/2024/01/03/air-force-recovers-black-box-deadly-osprey-crash-japan-search-remains-of-last-airman-continues.html

- ↑ "V-22 Osprey Makes Precautionary Landing En Route To UK". Air-Attack.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ↑ Castelli, Christopher J. (n.d.). "Navy Probes Multiple V-22 Surges, Stalls". NewsStand. InsideDefense.com. Retrieved 8 April 2007.

- 1 2 "Hydraulic Problems Vex V-22". Defensetalk.com. 5 April 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ↑ Bob Cox (31 March 2007). "Fire reported after leak of hydraulic fluid". Star-Telegram.com. Retrieved 8 April 2007.

- ↑ Trimble, Stephen. "V-22 Osprey severely damaged after engine fire". Flight Global, 8 November 2007.

- ↑ "V-22 mishap probe prompts US fleet restrictions". FlightGlobal, 4 December 2007.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ "Marine's fatal fall from Osprey". militarytimes.com

- ↑ "Deadly Osprey crash spurred safety changes". The San Diego Union-Tribune. 30 June 2015.

- ↑ "U.S. Commando Killed in Yemen in Trump's First Counterterrorism Operation". The New York Times. 29 January 2017.

- ↑ "US raid on al-Qaeda in Yemen: What we know so far". BBC News. 1 February 2017. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- Norton, Bill. Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey, Tiltrotor Tactical Transport. Midland Publishing, 2004. ISBN 1-85780-165-2.

- Whittle, Richard. The Dream Machine: The Untold History of the Notorious V-22 Osprey. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010. ISBN 1-4165-6295-8.