| 2 Kings 21 | |

|---|---|

The pages containing the Books of Kings (1 & 2 Kings) Leningrad Codex (1008 CE). | |

| Book | Second Book of Kings |

| Hebrew Bible part | Nevi'im |

| Order in the Hebrew part | 4 |

| Category | Former Prophets |

| Christian Bible part | Old Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 12 |

2 Kings 21 is the twenty-first chapter of the second part of the Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible or the Second Book of Kings in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible.[1][2] The book is a compilation of various annals recording the acts of the kings of Israel and Judah by a Deuteronomic compiler in the seventh century BCE, with a supplement added in the sixth century BCE.[3] This chapter records the events during the reign of Manasseh and Amon, the kings of Judah.[4][5]

Text

This chapter was originally written in the Hebrew language. It is divided into 26 verses.

Textual witnesses

Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter in Hebrew are of the Masoretic Text tradition, which includes the Codex Cairensis (895), Aleppo Codex (10th century), and Codex Leningradensis (1008).[6]

There is also a translation into Koine Greek known as the Septuagint, made in the last few centuries BCE. Extant ancient manuscripts of the Septuagint version include Codex Vaticanus (B; B; 4th century) and Codex Alexandrinus (A; A; 5th century).[7][lower-alpha 1]

Old Testament references

Analysis

A parallel pattern of sequence is observed in the final sections of 2 Kings between 2 Kings 11–20 and 2 Kings 21–25, as follows:[10]

- A. Athaliah, daughter of Ahab, kills royal seed (2 Kings 11:1)

- B. Joash reigns (2 Kings 11–12)

- C. Quick sequence of kings of Israel and Judah (2 Kings 13–16)

- D. Fall of Samaria (2 Kings 17)

- E. Revival of Judah under Hezekiah (2 Kings 18–20)

- D. Fall of Samaria (2 Kings 17)

- C. Quick sequence of kings of Israel and Judah (2 Kings 13–16)

- B. Joash reigns (2 Kings 11–12)

- A'. Manasseh, a king like Ahab, promotes idolatry and kills the innocence (2 Kings 21)

- B'. Josiah reigns (2 Kings 22–23)

- C'. Quick succession of kings of Judah (2 Kings 24)

- D'. Fall of Jerusalem (2 Kings 25)

- E'. Elevation of Jehoiachin (2 Kings 25:27–30)[10]

- D'. Fall of Jerusalem (2 Kings 25)

- C'. Quick succession of kings of Judah (2 Kings 24)

- B'. Josiah reigns (2 Kings 22–23)

Manasseh king of Judah (21:1–18)

The passage recording the reign of Manasseh consists of the 'introductory regnal form' (verses 1–3), the body/regnal account (verses 4–16; with major subunits in verses 4–5, 6–8, 9–15 and 16, each in the waw-consecutive narrative form) and the 'concluding regnal form' (verses 17–18).[11] Manasseh's 55-year reign is the longest of all the kings of Judah, but in the Books of Kings he is considered the worst king of the southern kingdom.[12] Manasseh behaved like Ahab, the king of Israel in Samaria:

- Introducing the worship of Baal and Asherah to Jerusalem (cf. verses 3, 7 with 1 Kings 16:32–33).

- Shedding innocent blood (cf. verse 16 with 1 Kings 18:4; 19:10; 21)

- Strongly opposed by prophets (verses 10–15; Ahab by Elijah).[12]

Later, his grandson, king Josiah, must abolish all the deities reintroduced by Manasseh (cf. 2 Kings 23).[12]

Manasseh was Assyria's vassal, that Assyrian sources mention as 'a bringer of tribute and as a military follower', without the slightest indication of resistance. This might be the reason for the length of his reign.[12]

Verse 1

- Manasseh was twelve years old when he began to reign, and he reigned fifty-five years in Jerusalem. His mother's name was Hephzibah.[13]

- Cross reference: 2 Chronicles 33:1

- "Reigned fifty-five years": in Thiele's chronology (improved by McFall), Manasseh became coregent (while his father was still the king) in September 697 BCE and became the sole king between September 687 and September 686 BCE until he died between September 643 and September 642 BCE.[14]

Two seals appeared on the antiquities market in Jerusalem (first reported in 1963), both bearing the inscription, "Belonging to Manasseh, son of the king."[15][16] As the term "son of the king" refers to royal princes, whether they eventually ascended the throne or not,[17] the seal is considered to be Manasseh's during his co-regency with his father.[18] It bears the same iconography of the Egyptian winged scarab as the seals attributed to King Hezekiah, recalling the alliance between Hezekiah and Egypt against the Assyrians (2 Kings 18:21; Isaiah 36:6), and may symbolize 'a desire to permanently unite the northern and southern kingdoms together with God's divine blessing'.[19] Jar handles bearing a stamp with a winged-beetle and the phrase LMLK ("to the king"), along with the name of a city, have been unearthed throughout ancient Judah as well as in a large administrative complex discovered outside of the old city of Jerusalem and used to hold olive oil, food, wine, etc. – goods that were paid as taxes to the king, dated to the reigns of Hezekiah (cf. "Hezekiah's storehouses"; 2 Chronicles 32:27–28) and Manasseh.[20][21] These artifacts provide the evidence of 'a complex and highly organized tax system in Judah' from the time of Hezekiah extending into the time of Manasseh, among others to pay the tribute to the Assyrians.[16]

Amon, king of Judah (21:19–26)

Amon, Manasseh's son and successor, is recorded to have 'walked in the way which his father walked' (verse 21), but, unlike his father, he had a short period of reign.[22] Then, 'the people of the land'—the same political group who brought down the 'evil' queen Athaliah, enabling the 'good' king Joash to seize the throne (2 Kings 11:18, 20)—intervene to 'punish the king's murderers' and place Josiah, Amon's son, on the throne.[22]

Verse 19

- Amon was twenty-two years old when he began to reign, and he reigned two years in Jerusalem. His mother's name was Meshullemeth the daughter of Haruz of Jotbah.[23]

- Cross reference: 2 Chronicles 33:21

- "Reigned two years": in Thiele's chronology (improved by McFall), Amon became king between September 643 and September 642 BCE and died between September 641 and September 640 BCE.[24]

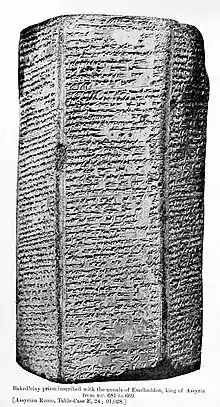

Archaeology

Manasseh and the kingdom of Judah are only mentioned in the list of subservient kings/states in Assyrian inscriptions of Esarhaddon and Ashurbanipal.[25] Manasseh is mentioned in the Esarhaddon Prism (dates to 673–672 BCE), discovered by archaeologist Reginald Campbell Thompson during the 1927–28 excavation season at the ancient Assyrian capital of Nineveh.[26] The 493 lines of cuneiform inscribed on the sides of the prism describe the history of King Esarhaddon's reign and an account of the reconstruction of the Assyrian palace in Babylon, which reads "Together 22 kings of Hatti [this land includes Israel], the seashore and the islands. All these I sent out and made them transport under terrible difficulties"; one of these 22 kings was King Manasseh of Judah ("Menasii šar [âlu]Iaudi").[26]

A record by Esarhaddon's son and successor, Ashurbanipal, mentions "Manasseh, king of Judah" who contributed to the invasion force against Egypt.[27] This was recorded on the "Rassam cylinder" (or "Rassam Prism", now in the British Museum), named after Hormuzd Rassam, who discovered it in the North Palace of Nineveh in 1854.[16] The ten-faced, cuneiform cylinder contains a record of Ashurbanipal's campaigns against Egypt and the Levant, that involved 22 kings "from the seashore, the islands and the mainland", who are called "servants who belong to me," clearly denoting them as Assyrian vassals.[28] Manasseh was one of the kings who 'brought tribute to Ashurbanipal and kissed his feet'.[16]

In rabbinic literature on "Isaiah" and Christian pseudepigrapha "Ascension of Isaiah", Manasseh is accused of executing the prophet Isaiah, who was identified as the maternal grandfather of Manasseh.[29][30][31]

Manasseh is mentioned in chapter 21 of 1 Meqabyan, a book considered canonical in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, where he is used as an example of ungodly king.[32]

See also

- Related Bible parts: 2 Kings 11, 2 Kings 23, 2 Chronicles 33

Notes

- ↑ The whole book of 2 Kings is missing from the extant Codex Sinaiticus.[8]

References

- ↑ Halley 1965, p. 211.

- ↑ Collins 2014, p. 288.

- ↑ McKane 1993, p. 324.

- ↑ Sweeney 2007, pp. 424–432.

- ↑ Dietrich 2007, pp. 262–263.

- ↑ Würthwein 1995, pp. 35–37.

- ↑ Würthwein 1995, pp. 73–74.

- ↑

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Codex Sinaiticus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Codex Sinaiticus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - 1 2 3 2 Kings 21, Berean Study Bible

- 1 2 Leithart 2006, p. 266.

- ↑ Sweeney 2007, p. 425.

- 1 2 3 4 Dietrich 2007, p. 262.

- ↑ 2 Kings 21:1 ESV

- ↑ McFall 1991, no. 56.

- ↑ Avigad, Nahman; Sass, Benjamin. (1997) Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals. (Jerusalem: The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, Israel Exploration Society, and The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, The Institute of Archaeology), p. 55.

- 1 2 3 4 Windle, Bryan (2021) "King Manasseh: An Archaeological Biography". Bible Archaeology Report. February 12, 2021.

- ↑ Avigad, Nahman (1963) "A Seal of 'Manasseh Son of the King'". Israel Exploration Journal. Vol. 13, No. 2, p. 135.

- ↑ "The Seal of Manasseh," NIV Archaeological Study Bible (ed. Walter C. Kaiser Jr and Duane Garrett; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2005), 565.

- ↑ Lubetski, Meir (2001) "King Hezekiah’s Seal Revisited." Biblical Archaeology Review. 27:4, July/August, p. 48.

- ↑ Borschel-Dan, Amanda "Huge Kingdom of Judah government complex found near US Embassy in Jerusalem." Times of Israel. 22 July 2020. (Accessed Feb. 10, 2021); apud Windle 2021

- ↑ "How Ancient Taxes Were Collected Under King Manasseh." Biblical Archaeology Society. Jan. 1, 2019. (Accessed Feb. 10, 2021); apud Windle 2021

- 1 2 Dietrich 2007, p. 263.

- ↑ 2 Kings 21:19 ESV

- ↑ McFall 1991, no. 57.

- ↑ Gane, Roy (1997) "The Role of Assyria in the Ancient Near East During the Reign of Mannaseh." Andrews University Seminary Studies, Spring 1997, Vol. 35, No. 1, pg. 22. Online: (Accessed Feb. 8, 2021).

- 1 2 "The Esarhaddon Prism". The British Museum. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

Column 4: "Adumutu (is) the strong city of the Arabians, which Sennacherib, king of Assyria, the father, my begetter, had conquered"

- ↑ Reinsch, Warren. Esarhaddon Prism Proves King Manasseh. An ancient Babylonian clay prism confirms two biblical kings and the accuracy of the Bible narrative. The Trumpet, May 2, 2019.

- ↑ Pritchard 1969, p. 294. Quote: "In my first campaign I marched against Egypt (Magan) and Ethiopia (Meluhha). Tirhakah (Targa), king of Egypt (Musur) and Nubia (Kicsu), whom Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, my own father, had defeated and in whose country he (Esarhaddon) had ruled, this (same) Tirhakah forgot’ the might of Ashur, Ishtar and the (other) great gods, my lords, and put his trust upon his own power …. (Then) I called up my mighty armed forces which Ashur and Ishtar have entrusted to me and took the shortest (lit .: straight) road to Egypt (Musur) and Nubia . During my march (to Egypt) 22 kings from the seashore, the islands and the mainland, Ba’al, king of Tyre, Manasseh (Mi-in-si-e), king of Judah (la-ti-di)…[etc.]…servants who belong to me, brought heavy gifts (tdmartu) to me and kissed my feet . I made these kings accompany my army over the lard-as well as (over) the sea-route with their armed forces and their ships."

- ↑ ""Hezekiah". Jewish Encyclopedia". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. 1906.

- ↑ Berakhot 10a: Manasseh's mother was apparently the daughter of the prophet Isaiah, and married King Hezekiah after his miraculous recovery

- ↑ Yevamot 49b: Manasseh judged Isaiah as a false witness for issuing statements contradicting the Torah. When Isaiah refused to defend himself and was miraculously swallowed within a cedar tree, Manasseh ordered that the tree be sawn in two, causing the prophet's death.

- ↑ Book of Meqabyan I - III. Torah of Yeshuah.

Sources

- Cogan, Mordechai; Tadmor, Hayim (1988). II Kings: A New Translation. Anchor Yale Bible Commentaries. Vol. 11. Doubleday. ISBN 9780385023887.

- Collins, John J. (2014). "Chapter 14: 1 Kings 12 – 2 Kings 25". Introduction to the Hebrew Scriptures. Fortress Press. pp. 277–296. ISBN 9781451469233.

- Coogan, Michael David (2007). Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: New Revised Standard Version, Issue 48 (Augmented 3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195288810.

- Dietrich, Walter (2007). "13. 1 and 2 Kings". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary (first (paperback) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 232–266. ISBN 978-0199277186. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- Fretheim, Terence E (1997). First and Second Kings. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25565-7.

- Halley, Henry H. (1965). Halley's Bible Handbook: an abbreviated Bible commentary (24th (revised) ed.). Zondervan Publishing House. ISBN 0-310-25720-4.

- Huey, F. B. (1993). The New American Commentary - Jeremiah, Lamentations: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture, NIV Text. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 9780805401165.

- Leithart, Peter J. (2006). 1 & 2 Kings. Brazos Theological Commentary on the Bible. Brazos Press. ISBN 978-1587431258.

- McFall, Leslie (1991), "Translation Guide to the Chronological Data in Kings and Chronicles" (PDF), Bibliotheca Sacra, 148: 3–45, archived from the original (PDF) on August 27, 2010

- McKane, William (1993). "Kings, Book of". In Metzger, Bruce M; Coogan, Michael D (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. pp. 409–413. ISBN 978-0195046458.

- Nelson, Richard Donald (1987). First and Second Kings. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22084-6.

- Pritchard, James B (1969). Ancient Near Eastern texts relating to the Old Testament (3 ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691035031.

- Sweeney, Marvin (2007). I & II Kings: A Commentary. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22084-6.

- Thiele, Edwin R. (1951). The Mysterious Numbers of the Hebrew Kings: A Reconstruction of the Chronology of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Würthwein, Ernst (1995). The Text of the Old Testament. Translated by Rhodes, Erroll F. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0788-7. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

External links

- Jewish translations:

- Melachim II - II Kings - Chapter 21 (Judaica Press). Hebrew text and English translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- Christian translations:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- 2 Kings chapter 21. Bible Gateway