The Earl of Shaftesbury | |

|---|---|

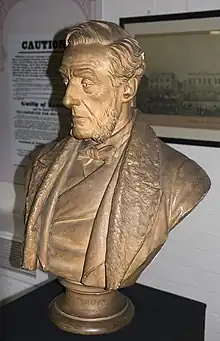

Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftsbury by John Collier | |

| Successor | The 8th Earl of Shaftesbury |

| Known for | Philanthropy |

| Years active | 44 years |

| Born | 28 April 1801 24 Grosvenor Square, Mayfair, London, England |

| Died | 1 October 1885 (aged 84) 12 Clifton Gardens, Folkestone, Kent, England |

| Cause of death | Inflammation of the lungs |

| Buried | The parish church on his estate at Wimborne St Giles, Dorset |

| Nationality | British |

| Spouse(s) | Lady Emily Cowper |

| Issue | 10 |

| Parents | Cropley Ashley-Cooper, 6th Earl of Shaftesbury Lady Anne Spencer |

Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury KG (28 April 1801 – 1 October 1885[1]), styled Lord Ashley from 1811 to 1851, was a British Tory politician, philanthropist, and social reformer. He was the eldest son of the 6th Earl of Shaftesbury and Lady Anne Spencer (daughter of the 4th Duke of Marlborough), and elder brother of Henry Ashley, MP. A social reformer who was called the "Poor Man's Earl", he campaigned for better working conditions, reform to lunacy laws, education and the limitation of child labour. He was also an early supporter of the Zionist movement and the YMCA and a leading figure in the evangelical movement in the Church of England.

Early life

Lord Ashley, as he was styled until his father's death in 1851,[2] was educated at Manor House school in Chiswick, London (1812–1813), Harrow School (1813–1816) and Christ Church, Oxford, where he gained first-class honours in classics in 1822, took his MA in 1832 and was appointed DCL in 1841.[3] Whilst at Oxford, he joined the Apollo University Lodge.[4]

Ashley's early family life was loveless, a circumstance common among the British upper classes.[5] G. F. A. Best, in his biography Shaftesbury, writes that "Ashley grew up without any experience of parental love. He saw little of his parents, and when duty or necessity compelled them to take notice of him they were formal and frightening."[6] Even as an adult, he disliked his father and was known to refer to his mother as "a devil".

This difficult childhood was softened by the affection he received from the family housekeeper Maria Millis, and his sisters. Millis provided for Ashley a model of Christian love that would form the basis for much of his later social activism and philanthropic work, as Best explains: "What did touch him was the reality, and the homely practicality, of the love which her Christianity made her feel towards the unhappy child. She told him bible stories, she taught him a prayer."[7] Despite this powerful reprieve, school became another source of misery for the young Ashley, whose education at Manor House from 1808 to 1813 introduced a "more disgusting range of horrors".[6] Shaftesbury himself shuddered to recall those years: "The place was bad, wicked, filthy; and the treatment was starvation and cruelty."[6]

By his teenage years Ashley had become a committed Christian, and whilst at Harrow he had two experiences which influenced his later life. "Once, at the foot of Harrow Hill, he was the horrified witness of a pauper's funeral. The drunken pallbearers, stumbling along with a crudely-made coffin and shouting snatches of bawdy songs, brought home to him the existence of a whole empire of callousness which put his own childhood miseries in their context. The second incident was his unusual choice of a subject for a Latin poem. In the school grounds, there was an unsavoury mosquito-breeding pond called the Duck Puddle. He chose it as his subject because he was urgently concerned that the school authorities should do something about it, and this appeared to be the simplest way of bringing it to their attention. Soon afterwards the Duck Puddle was inspected, condemned and filled in. This little triumph was a useful fillip to his self-confidence, but it was more than that. It was a foretaste of his skill in getting people to act decisively in face of sloth or immediate self-interest. This was to prove one of his greatest assets in Parliament."[8]

Political career

Ashley was elected as the Tory Member of Parliament for Woodstock (at that time a pocket borough controlled by the Duke of Marlborough) in June 1826 and was a strong supporter of the Duke of Wellington.[3] After George Canning replaced Lord Liverpool as Prime Minister, he offered Ashley a place in the new government, despite Ashley having been in the Commons for only five months. Ashley politely declined, writing in his diary that he believed that serving under Canning would be a betrayal of his allegiance to the Duke of Wellington and that he was not qualified for office.[9] Before he had completed one year in the Commons, he had been appointed to three parliamentary committees and he received his fourth such appointment in June 1827, when he was appointed to the Select Committee on Pauper Lunatics in the County of Middlesex and on Lunatic Asylums.[10]

Reform of the Lunacy laws

.jpg.webp)

In 1827, when Ashley-Cooper was appointed to the Select Committee on Pauper Lunatics in the County of Middlesex and on Lunatic Asylums, the majority of lunatics in London were kept in madhouses owned by Dr Warburton. The Committee examined many witnesses concerning one of his madhouses in Bethnal Green, called the White House. Ashley visited this on the committee's behalf. The patients were chained up, slept naked on straw, and excreted in their beds. They were left chained from Saturday afternoon until Monday morning when they were cleared of the accumulated excrement. They were then washed down in freezing cold water and one towel was allotted to 160 people, with no soap. It was overcrowded, and the meat provided was "that nasty thick hard muscle a dog could not eat". The White House had been described as "a mere place for dying" rather than curing the insane and when the Committee asked Dr MacMichael whether he believed that "in the lunatic asylums in the neighbourhood of London any curative process is going on with regard to pauper patients", he replied: "None at all".[11]

The Committee recommended that "legislative measures of a remedial character should be introduced at the earliest period at the next session", and the establishment of a Board of Commissioners appointed by the Home Secretary possessing extensive powers of licensing, inspection and control.[12] When in February 1828 Robert Gordon, Liberal MP for Cricklade, introduced a bill to put these recommendations into law, Ashley seconded this and delivered his maiden speech in support of the Bill. He wrote in his diary: "So, by God's blessing, my first effort has been for the advance of human happiness. May I improve hourly! Fright almost deprived me of recollection but again thank Heaven, I did not sit down quite a presumptuous idiot". Ashley was also involved in framing the County Lunatic Asylums (England) Act 1828 and the Madhouses Act 1828. Through these Acts, fifteen commissioners were appointed for the London area and given extensive powers of licensing and inspection, one of the commissioners being Ashley.[13]

In July 1845, Ashley sponsored two Lunacy Acts, 'For the Regulation of lunatic Asylums' and 'For the better Care and Treatment of Lunatics in England and Wales'. They originated in the Report of the Commissioners in Lunacy which he had commended to Parliament the year before. These Acts consolidated and amended previous lunacy laws, providing better record keeping and more strict certification regulations to ensure patients against unwarranted detention. They also ordered, instead of merely permitting, the construction of country lunatic asylums and establishing an ongoing Lunacy Commission with Ashley as its chairman.[14] In support of these measures, Ashley gave a speech in which he claimed that although since 1828 there had been an improvement, more still needed to be done. He cited the case of a Welsh lunatic girl, Mary Jones, who had for more than a decade been locked in a tiny loft with one boarded-up window with little air and no light. The room was extremely filthy and filled with an intolerable smell. She could only squat in a bent position in the room and this had caused her to become deformed.[15]

In early 1858, a Select Committee was appointed over concerns that sane persons were detained in lunatic asylums. Lord Shaftesbury (as Ashley had become upon his father's death in 1851) was the chief witness and opposed the suggestion that the certification of insanity be made more difficult and that early treatment of insanity was essential if there was to be any prospect of a cure. He claimed that only one or two people in his time dealing with lunacy had been detained in an asylum without sufficient grounds and that commissioners should be granted more not fewer powers. The committee's Report endorsed all of Shaftesbury's recommendations except for one: that a magistrate's signature on a certificate of lunacy be made compulsory. This was not put into law chiefly due to Shaftesbury's opposition to it. The Report also agreed with Shaftesbury that unwarranted detentions were "extremely rare".[16]

In July 1877, Shaftesbury gave evidence before the Select Committee on the Lunacy Laws, which had been appointed in February over concerns that it was too easy for sane persons to be detained in asylums. Shaftesbury feared that because of his advanced age he would be taken over by forgetfulness whilst giving evidence and was greatly stressed in the months leading up to this: "Shall fifty years of toil, anxiety and prayer, crowned by marvellous and unlooked-for success, bring me in the end only sorrow and disgrace?" When "the hour of trial" arrived Shaftesbury defended the Lunacy Commission and claimed he was now the only person alive who could speak with personal knowledge of the state of care of lunatics before the Lunacy Commission was established in 1828. It had been "a state of things such as would pass all belief". In the committee's Report, the members of the Committee agreed with Shaftesbury's evidence on all points.[17]

In 1884, the husband of Mrs Georgina Weldon tried to have her detained in a lunatic asylum because she believed that her pug dog had a soul and that the spirit of her dead mother had entered into her pet rabbit. She commenced legal action against Shaftesbury and other lunacy commissioners although it failed. In May, Shaftesbury spoke in the Lords against a motion declaring the lunacy laws unsatisfactory but the motion passed Parliament. The Lord Chancellor Selborne supported a Lunacy Law Amendment Bill and Shaftesbury wanted to resign from the Lunacy Commission as he believed he was honour bound not to oppose a Bill supported by the Lord Chancellor. However, Selborne implored him not to resign so Shaftesbury refrained. However, when the Bill was introduced and it contained the provision which made it compulsory for a certificate of lunacy to be signed by a magistrate or a judge, he resigned. The government fell, however, and the Bill was withdrawn and Shaftesbury resumed his chairmanship of the Lunacy Commission.[18]

Shaftesbury's work in improving the care of the insane remains one of his most important, though lesser known, achievements. He wrote: "Beyond the circle of my own Commissioners and the lunatics that I visit, not a soul, in great or small life, not even my associates in my works of philanthropy, has any notion of the years of toil and care that, under God, I have bestowed on this melancholy and awful question".[19]

Child labour

In March 1833, Ashley introduced the Ten Hours Act 1833 into the Commons, which provided that children working in the cotton and woollen industries must be aged nine or above; no person under the age of eighteen was to work more than ten hours a day or eight hours on a Saturday; and no one under twenty-five was to work nights, insisted they should go to school, and appointed inspectors to enforce the law.[20] However the Whig government, by a majority of 145, amended this to substitute "thirteen" in place of "eighteen" and the Act as it passed ensured that no child under thirteen worked more than nine hours.

In June 1836, another Ten Hours act was introduced into the Commons and although Ashley considered this Bill ill-timed, he supported it. In July one member of the Lancashire committees set up to support the Bill wrote that: "If there was one man in England more devoted to the interests of the factory people than another, it was Lord Ashley. They might always rely on him as a ready, steadfast and willing friend".[21] In July 1837, he accused the government of ignoring the breaches of the 1833 Act and moved the resolution that the House regretted the regulation of the working hours of children had been found to be unsatisfactory. It was lost by fifteen votes.[21]

The text of A Narrative of the Experience and Sufferings of William Dodd a Factory Cripple was sent to Lord Ashley and with his support was published in 1840.[22] Ashley employed William Dodd at 45 shillings a week, and he wrote The Factory System: Illustrated to describe the conditions of working children in textile manufacture. This was published in 1842.[23] These books were attacked by John Bright in parliament who said that he had evidence that the books described Dodd's mistreatment but were in fact driven by Dodd's ingratitude as a disgruntled employee. Ashley sacked Dodd who emigrated to America.[24]

In 1842, Ashley wrote twice to the Prime Minister, Robert Peel, to urge the government to support a new Factory Act. Peel wrote in reply that he would not support one, and Ashley wrote to the Short Time Committees of Cheshire, Lancashire and Yorkshire who desired a Ten Hours Act:

Though painfully disappointed, I am not disheartened, nor am I at a loss either what course to take, or what advice to give. I shall persevere unto my last hour, and so must you; we must exhaust every legitimate means that the Constitution afford, in petitions to Parliament, in public meetings, and in friendly conferences with your employers; but you must infringe no law, and offend no proprieties; we must all work together as sensible men, who will one day give an account of their motives and actions; if this course is approved, no consideration shall detach me from your cause; if not, you must elect another advocate.

I know that, in resolving on this step, I exclude myself altogether from the tenure of office; I rejoice in the sacrifice, happy to devote the remainder of my days, be they many or be they few, as God in His wisdom shall determine, to an effort, however laborious, to ameliorate your moral and social condition.

In March 1844, Ashley moved an amendment to a Factory Bill limiting the working hours of adolescents to ten hours after Sir James Graham had introduced a Bill aiming to limit their working hours to twelve hours. Ashley's amendment was passed by eight votes, the first time the Commons had approved of the Ten Hour principle. However, in a later vote, his amendment was defeated by seven votes and the Bill was withdrawn.[25] Later that month, Graham introduced another Bill which again would limit the employment of adolescents to twelve hours. Ashley supported this Bill except that he wanted ten hours not twelve as the limit. In May he moved an amendment to limit the hours worked to ten hours but this was lost by 138 votes.[26]

In 1846, whilst he was out of Parliament, Ashley strongly supported John Fielden's Ten Hours Bill, which was lost by ten votes.[27] In January 1847, Fielden reintroduced his Bill and it finally passed through Parliament to become the Ten Hours Act.[28]

Miners

Ashley introduced the Mines and Collieries Act 1842 in Parliament to outlaw the employment of women and children underground in coal mines. He made a speech in support of the Act and the Prince Consort wrote to him afterwards, sending him the "best wishes for your total success". At the end of his speech, his opponent on the Ten Hours issue, Cobden, walked over to Ashley and said: "You know how opposed I have been to your views, but I don't think I have ever been put into such a frame of mind in the whole course of my life as I have been by your speech."[29]

Climbing boys

Ashley was a strong supporter of prohibiting the employment of boys as chimney sweeps. Many climbing boys were illegitimate who had been sold by their parents. They had scorched and lacerated skin, their eyes and throats filled with soot, with the danger of suffocation and their occupational disease—cancer of the scrotum.[30] In 1840, a Bill was introduced into the Commons outlawing the employment of boys as chimney sweeps, and strongly supported by Ashley. Despite being enforced in London, elsewhere the Act did not stop the employment of child chimney sweeps and this led to the foundation of the Climbing-Boys' Society with Ashley as its chairman. In 1851, 1853 and 1855, Shaftesbury introduced Bills into Parliament to deal with the ongoing use of boy chimney sweeps but these were all defeated. He succeeded in passing the Chimney Sweepers Regulation Act 1864 but, like its predecessors, it remained ineffectual. Shaftesbury finally persuaded Parliament to pass the Chimney Sweepers Act 1875 which ensured the annual licensing of chimney sweeps and the enforcement of the law by the police. This finally eradicated the employment of boys as chimney sweeps.[31]

After Shaftesbury discovered that a boy chimney sweep was living behind his house in Brock Street, London, he rescued the child and sent him to "the Union School at Norwood Hill, where, under God's blessing and special merciful grace, he will be trained in the knowledge and love and faith of our common Saviour".[32]

Education reform

In 1844, Ashley became president of the Ragged School Union that promoted ragged schools. These schools were for poor children and sprang up from volunteers. Ashley wrote that "If the Ragged School system were to fail I should not die in the course of nature, I should die of a broken heart".[33]

Housing reform

In 1851 two acts were passed at Shaftesbury's insistence concerning lodging houses. This marked, according to one study, "the first attempt of the legislature to grapple with the question of unhealthy dwellings." The Common Lodging Houses Act 1851, which Charles Dickens described as 'the best measure ever passed in Parliament,' provided for all such lodging houses to be registered and "that no lodgers were to be kept until the houses had been inspected and opened by an officer of the local authority." In addition, local authorities were given the power to make regulations for common-lodging houses and exact penalties for regulation breaches. Regular cleansing and whitewashing were enforced while it was rendered compulsory "for the keeper of a lodging-house to give immediate notice of any case of fever or infectious disease in the house to the local authority, to the Poor Law medical officer and the relieving officer."[34] The Labouring Classes Lodging Houses Act 1851 "empowered borough councils and local boards to erect lodging-houses or to purchase existing lodging-houses, and to manage them, making by-laws for charges, management, etc. Such lodging-houses were under the inspection of the local boards of health."[35]

Religious restoration

Zionist movement

Shaftesbury was a pre-millennial evangelical Anglican who believed in the imminent second coming of Christ. His belief underscored the urgency of immediate action. He strongly opposed Roman Catholic Church ritualism among High Church Anglicans. He also disapproved of the Catholic features of the Oxford Movement in the Church of England. He denounced the Maynooth College Act 1845, which funded the Catholic seminary in Ireland that would train many priests.[3] However, disagreeing with his father, he favored Catholic Emancipation.[36]

Shaftesbury was a leading figure within 19th-century evangelical Anglicanism.[37] Shaftesbury was President of the British and Foreign Bible Society (BFBS) from 1851 until his death in 1885. He wrote, of the Bible Society, "Of all Societies, this is nearest to my heart... Bible Society has always been a watchword in our house." He was also president of the Evangelical Alliance for some time.[2]

Shaftesbury was also a student of Edward Bickersteth and the two men became prominent advocates of Christian Zionism in Britain.[38][39] Shaftesbury was an early proponent of the Restoration of the Jews to the Holy Land, providing the first proposal by a major politician to resettle Jews in Palestine. The conquest of Greater Syria in 1831 by Muhammad Ali of Egypt changed the conditions under which European power politics operated in the Near East. As a consequence of that shift, Shaftesbury was able to help persuade Foreign Minister Palmerston to send a British consul, James Finn, to Jerusalem in 1838. A committed Christian and a loyal Englishman, Shaftesbury argued for a Jewish return because of what he saw as the political and economic advantages Britain would gain from this and because he believed that it was God's will. In January 1839, Shaftesbury published an article in the Quarterly Review, which although initially commenting on the 1838 Letters on Egypt, Edom and the Holy Land (1838) by Lord Lindsay, provided the first proposal by a major politician to resettle Jews in Palestine:[40][41] In 1848, Shaftesbury became president of the London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews,[42] of which Finn was a prominent member.

The soil and climate of Palestine are singularly adapted to the growth of produce required for the exigencies of Great Britain; the finest cotton may be obtained in almost unlimited abundance; silk and madder are the staple of the country, and olive oil is now, as it ever was, the very fatness of the land. Capital and skill are alone required: the presence of a British officer, and the increased security of property which his presence will confer, may invite them from these islands to the cultivation of Palestine; and the Jews, who will betake themselves to agriculture in no other land, having found, in the English consul, a mediator between their people and the Pacha, will probably return in yet greater numbers, and become once more the husbandmen of Judaea and Galilee.

The lead-up to the Crimean War (1854), like the military expansionism of Muhammad Ali two decades earlier, signalled an opening for realignments in the Near East. In July 1853, Shaftesbury wrote to the Prime Minister, Lord Aberdeen, that Greater Syria was "a country without a nation" in need of "a nation without a country... Is there such a thing? To be sure there is, the ancient and rightful lords of the soil, the Jews!" In his diary that year he wrote "these vast and fertile regions will soon be without a ruler, without a known and acknowledged power to claim dominion. The territory must be assigned to some one or other... There is a country without a nation; and God now in his wisdom and mercy, directs us to a nation without a country."[lower-alpha 1][43] This is commonly cited as an early use of the phrase "A land without a people for a people without a land" by which Shaftesbury was echoing another British proponent of the restoration of the Jews to Palestine, Dr Alexander Keith.

Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade

Shaftesbury served as the first president of the Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade: a lobbying group dedicated to the abolition of the opium trade. The Society was formed by Quaker businessmen in 1874, and Shaftesbury was president from 1880 until his death.[44] The Society's efforts eventually led to the creation of the investigative Royal Commission on Opium.[45]

Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain

The Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain in Piccadilly Circus, London, erected in 1893, was designed to commemorate his philanthropic works. The fountain is crowned by Alfred Gilbert's aluminium statue of Anteros as a nude, butterfly-winged archer. This is officially titled The Angel of Christian Charity, but has become popularly if mistakenly known as Eros. It appears on the masthead of the Evening Standard.

Veneration

Lord Shaftesbury was a member of the Canterbury Association, as were two of Wilberforce's sons, Samuel and Robert. Lord Ashley joined on 27 March 1848.[46]

Anthony Ashley Cooper is remembered in the Church of England with a commemoration on 1 October.[47]

Family

Lord Shaftesbury, then Lord Ashley, married Lady Emily Caroline Catherine Frances Cowper (died 15 October 1872), daughter of Peter Cowper, 5th Earl Cowper and Emily Lamb, Countess Cowper; Emily is likely in fact to have been the natural daughter of Lord Palmerston (later her official stepfather), on 10 June 1830. This marriage, which proved a happy and fruitful one, produced ten children.[48] It also provided invaluable political connections for Ashley; his wife's maternal uncle was Lord Melbourne and her stepfather (and supposed biological father) Lord Palmerston, both prime ministers.

The children, who mostly had various degrees of ill-health, were:[49]

- Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 8th Earl of Shaftesbury (27 June 1831 – 13 April 1886), ancestor of all subsequent earls.[lower-alpha 2] He proved to be a disappointing heir apparent, constantly running up debts with his extravagant wife Harriet, born Lady Harriet Chichester.[lower-alpha 3]

- (Anthony) Francis Henry Ashley-Cooper, second son (b. 13 March 1833[50] – 13 May 1849)[51][49]

- (Anthony) Maurice William Ashley-Cooper, third son (22 July 1835 – 19 August 1855), died aged 20, after several years of illness.[49][52]

- (Anthony) Evelyn Melbourne Ashley (24 July 1836 – 15 November 1907), married firstly 28 July 1866 Sybella Charlotte Farquhar (c. 1846 – 31 August 1886), daughter of Sir Walter Rockcliffe Farquhar, 3rd Bt. by his wife Lady Mary Octavia Somerset, a daughter of the Duke of Beaufort and had one son Wilfred William Ashley, and one daughter. His granddaughter was Edwina Ashley, later Lady Mountbatten (1901–1960), who had two daughters Patricia, Countess Mountbatten of Burma (1924-2017) and Lady Pamela Hicks (b. 1929). Evelyn Ashley left several other descendants via his daughter and Edwina's younger sister. Evelyn Ashley married 2ndly 30 June 1891 Lady Alice Elizabeth Cole (4 February 1853 – 25 August 1931), daughter of William Willoughby Cole, 3rd Earl of Enniskillen by his first wife Jane Casamajor, no issue. Evelyn Melbourne Ashley died on 15 November 1907.

- Lady Victoria Elizabeth Ashley, later Lady Templemore (23 September 1837[49][52] – 15 February 1927), married 8 January 1873 (aged 35) St George's, Hanover Square, London Harry Chichester, 2nd Baron Templemore (4 June 1821 – 10 June 1906), son of Arthur Chichester, 1st Baron Templemore and Lady Augusta Paget, and had issue.[lower-alpha 4]

- (Anthony) Lionel George Ashley-Cooper (b. 7 September 1838 – 1914).[49] He married 12 December 1868 Frances Elizabeth Leigh "Fanny (d. 12 August 1875), daughter of Capel Hanbury Leigh;[51] apparently had no issue.

- Lady Mary Charlotte Ashley-Cooper, second daughter (25 July 1842[49][lower-alpha 5] – 3 September 1861[49][lower-alpha 6]).

- Lady Constance Emily Ashley-Cooper, third daughter, or "Conty" (29 November 1845 – 16 December 1872[49] or 1871[53] of lung disease[54]).

- Lady Edith Florence Ashley-Cooper, fourth daughter (1 February 1847 – 25 November 1913)[49][53]

- (Anthony) Cecil Ashley-Cooper, sixth son and tenth and youngest child (8 August 1849 – 23 September 1932);[49] apparently died unmarried.

Legacy

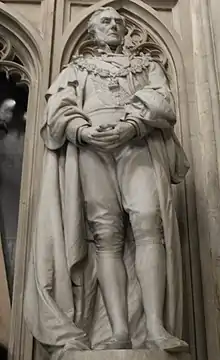

Although he was offered a burial at Westminster Abbey, Shaftesbury wished to be buried at St. Giles. George Williams (YMCA) chaired the organising committee of his funeral, and was a pall-bearer at it.[55] A funeral service was held in Westminster Abbey during the early morning of 8 October and the streets along the route from Grosvenor Square and Westminster Abbey were thronged with poor people, costermongers, flower-girls, boot-blacks, crossing-sweepers, factory-hands and similar workers who waited for hours to see Shaftesbury's coffin as it passed by. Due to his constant advocacy for the better treatment of the working classes, Shaftesbury became known as the "Poor Man's Earl".[3] A white marble statue commemorates Shaftesbury near the west door of Westminster Abbey.[56]

One of his biographers, Georgina Battiscombe, has claimed that "No man has in fact ever done more to lessen the extent of human misery or to add to the sum total of human happiness".[57]

Three days after his death, Charles Spurgeon eulogised him, saying:

During the past week the church of God, and the world at large, have sustained a very serious loss. In the taking home to Himself by our gracious Lord of the Earl of Shaftesbury, we have, in my judgment, lost the best man of the age. I do not know whom I should place second, but I certainly should put him first—far beyond all other servants of God within my knowledge—for usefulness and influence. He was a man most true in his personal piety, as I know from having enjoyed his private friendship; a man most firm in his faith in the gospel of our Lord Jesus Christ; a man intensely active in the cause of God and truth. Take him whichever way you please, he was admirable: he was faithful to God in all his house, fulfilling both the first and second commands of the law in fervent love to God, and hearty love to man. He occupied his high position with singleness of purpose and immovable steadfastness: where shall we find his equal? If it is not possible that he was absolutely perfect, it is equally impossible for me to mention a single fault; for I saw none. He exhibited scriptural perfection, inasmuch as he was sincere, true, and consecrated. Those things which have been regarded as faults by the loose thinkers of this age are prime virtues in my esteem. They called him narrow; and in this they bear unconscious testimony to his loyalty to truth. I rejoiced greatly in his integrity, his fearlessness, his adherence to principle, in a day when revelation is questioned, the gospel explained away, and human thought set up as the idol of the hour. He felt that there was a vital and eternal difference between truth and error; consequently, he did not act or talk as if there was much to be said on either side, and, therefore, no one could be quite sure. We shall not know for many a year how much we miss in missing him; how great an anchor he was to this drifting generation, and how great a stimulus he was to every movement for the benefit of the poor. Both man and beast may unite in mourning him: he was the friend of every living thing. He lived for the oppressed; he lived for London; he lived for the nation; he lived still more for God. He has finished his course; and though we do not lay him to sleep in the grave with the sorrow of those that have no hope, yet we cannot but mourn that a great man and a prince has fallen this day in Israel. Surely, the righteous are taken away from the evil to come, and we are left to struggle on under increasing difficulties.[58]

See also

- London Society for Promoting Christianity Among the Jews – Shaftesbury was president of the society.

- A land without a people for a people without a land

- Christian Zionism

- YMCA - Shaftesbury served as YMCA's first president from 1851 until his death in 1885.[59]

Notes

- ↑ Shaftsbury as cited in Hyamson 1918, p. 140

- ↑ He was father of the 9th Earl (1869–1961), whose elder son Lord Ashley was father of the ill-fated 10th Earl (1938–2004, murdered by an estranged third wife), father of the 11th Earl (1977–2005) and the 12th Earl (b. 1979). Ironically, despite the 7th Earl's six sons, only the eldest son's heirs male survive to the present, in the person of the 12th Earl, last of his line. Other lines, including that of the reformer Lord Shaftesbury's four brothers, had all died out by 1986 (the death, without sons, of the John Ashley-Cooper, younger son of the 9th Earl).

- ↑ Finlayson 2004, pp. 500–504 p. 501 in particular refers to the future 8th Earl's debts, but there are other references. Page 500 refers to the birth of the future 9th Earl in 1869

- ↑ Lord Templemore's heir male and descendant is the present Marquess of Donegall; his father inheriting that title in 1975.

- ↑ According to Finlayson 2004, p. 196, Countess Emily nearly suffered a miscarriage, and did indeed have a miscarriage in 1843.

- ↑ also see Finlayson 2004, p. 427, however, Finlayson 2004, p. 504 gives a different date 1860.

References

Citations

- ↑ "Hall of fame: Anthony Ashley Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury". The Gazette.

- 1 2 Smith 1906, p. 277.

- 1 2 3 4 Wolffe 2008.

- ↑ Crook, Joe Mordaunt; Daniel, James W. (2019). Oxford Freemasons: A Social History of the Apollo University Lodge (First ed.). Oxford: Bodleian Library. ISBN 9781851244676.

- ↑ Best 1964, p. 14.

- 1 2 3 Best 1964, p. 15.

- ↑ Best 1964, p. 16.

- ↑ Hewitt 1950.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, p. 28.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, p. 31.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, p. 37.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, p. 182.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, pp. 182–183.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, p. 259.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, pp. 319–320.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, pp. 330–331.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, p. 318.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, pp. 88, 91.

- 1 2 Battiscombe 1974, p. 109.

- ↑ Simkin 1997a.

- ↑ "Timeline: Anthony Ashley Cooper (1801-1885)". historymole.com. 18 September 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ↑ Simkin 1997b.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, p. 171.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, p. 175.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, p. 199.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, p. 202.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, p. 127.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, p. 196.

- ↑ Conservative social and industrial reform: A record of Conservative legislation between 1800 and 1974 by Charles E, Bellairs, P.13-14

- ↑ Conservative social and industrial reform: A record of Conservative legislation between 1800 and 1974 by Charles E, Bellairs, P.14

- ↑ "Ashley Cooper, Anthony, Lord Ashley (1801-1885)". The History of Parliament. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ↑ Chapman 2006, p. 61.

- ↑ Larsen 1998, p. 463.

- ↑ Lewis 2014, p. 380.

- ↑ Lindsay 1839, p. 93.

- ↑ Sokolow 1919.

- ↑ Wigram 1866, p. 2.

- ↑ Garfinkle 1991.

- ↑ Coats 1995, p. 47.

- ↑ Coats 1995, p. 48.

- ↑ Blain 2007, pp. 12–13, 89–92.

- ↑ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 8 April 2021.

- ↑ Irwin 1976.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Descendants of John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough 1650-1722 (gen 6 (31-60) of 6 generations". brigittegastelancestry.com. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ↑ Finlayson 2004, p. 94.

- 1 2 Finlayson 2004, p. 622.

- 1 2 Finlayson 2004, p. 130.

- 1 2 Finlayson 2004, p. 621.

- ↑ Finlayson 2004, p. 504.

- ↑ Binfield 1994, p. 20.

- ↑ "Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury". Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ↑ Battiscombe 1974, p. 334.

- ↑ "Departed Saints Yet Living", The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit Sermons, vol. 31. London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1885. pp. 541–542.

- ↑ Cannon & Crowcroft 2015.

Sources

- Battiscombe, Georgina (1974). Shaftesbury: A Biography of the Seventh Earl, 1801-1885. Constable. ISBN 9780094578401.

- Best, Geoffrey (1964). Shaftesbury. New York: Arco.

- Blain, Rev. Michael (2007). The Canterbury Association (1848–1852): A Study of Its Members' Connections (PDF). Christchurch: Project Canterbury. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- Cannon, John; Crowcroft, Robert (2015). A Dictionary of British History. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-104480-9.

- Binfield, Clyde (1994). George Williams in Context: a Portrait of the Founder of the YMCA. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

- Chapman, Mark (2006). Anglicanism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280693-2.

- Coats, A.W. Bob (1995). The Economic Review. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-13135-3.

- Smith, Benjamin E., ed. (1906). "Cooper, Anthony Ashley". The Century Cyclopedia of Names. New York: The Century Company.

- Finlayson, Geoffrey (2004). The Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, 1801-1885. Regent College. ISBN 978-1-57383-314-1.

- Garfinkle, Adam M. (October 1991), "On the Origin, Meaning, Use and Abuse of a Phrase", Middle Eastern Studies, London, 27 (4): 539–550, doi:10.1080/00263209108700876, JSTOR 4283461

- Hewitt, Gordon (1950). "Ch. II Grand Seigneur —Good Samaritan". Lord Shaftesbury, 1801-1885. Great Churchmen No. 18. Church Book Room Press. ASIN B0000CHTD9. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016.

- Hyamson, Albert (1918). "British Projects for the Restoration of Jews to Palestine". Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society (26): 127–164. JSTOR 43059305.

- Irwin, Grace (1976). The Seventh Earl: A Dramatized Biography. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6059-0.

- Larsen, David L. (1998). Company of the Preachers. Vol. 2. Kregel. ISBN 978-0-8254-3086-2.

- Lewis, Donald M. (2 January 2014). The Origins of Christian Zionism: Lord Shaftesbury and Evangelical Support for a Jewish Homeland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-63196-0.

- Lindsay, Alexander (1839). "Letters on Egypt, Edom and the Holy Land". The London Quarterly Review. Theodore Foster. 63 (CXXV).

- Masalha, Nur (2014). The Zionist Bible: Biblical Precedent, Colonialism and the Erasure of Memory. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-54465-4.

- Simkin, John (September 1997). "Lord Ashley, Earl of Shaftesbury". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Simkin, John (September 1997). "William Dodd". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Sokolow, Nahum (1919). History of Zionism, 1600-1918. Longmans, Green and Company.

- Wigram, Joseph Cotton (1866). Report of the Conference upon the Rosenthal case, held with the representatives of the Committee of the London Society for promoting Christianity amongst the Jews. London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer.

- Wolffe, John (3 January 2008). "Cooper, Anthony Ashley-, seventh Earl of Shaftesbury (1801–1885)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6210. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Further reading

- Bready, John Wesley (1926). Lord Shaftesbury and Social-industrial Progress. G. Allen & Unwin.

- Debrett, John (1999). The Peerage of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland: England. Adegi. ISBN 978-1-4021-5954-1.

- Finlayson, Geoffrey (March 1983). "The Victorian Shaftesbury". History Today. Vol. 33, no. 3. pp. 31–35.

- Furse-Roberts, David Andrew Barton (2015). The Making of an Evangelical Tory: The Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury (1801-1885) and the Evolving Character of Victorian Evangelicalism (PhD). University of New South Wales. hdl:1959.4/55240.

- Hammond, J. L.; Hammond, B. (1923). Lord Shaftesbury. London: Constable.

- Hodder, Edwin (1886). The Life and Work of the Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury, K.G. Vol. 1. Cassell. ISBN 9780790552767. Volume2; Volume 3