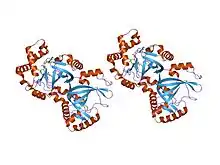

| ADPrib_exo_Tox | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

crystal structure of the enzymatic component of iota-toxin from clostridium perfringens with nadh | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | ADPrib_exo_Tox | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF03496 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0084 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR003540 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1giq / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

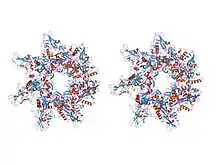

| Binary_toxB | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

crystal structure of the anthrax toxin protective antigen heptameric prepore | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Binary_toxB | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF03495 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR003896 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1acc / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| TCDB | 1.C.42 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The AB toxins are two-component protein complexes secreted by a number of pathogenic bacteria, though there is a pore-forming AB toxin found in the eggs of a snail.[1] They can be classified as Type III toxins because they interfere with internal cell function.[2] They are named AB toxins due to their components: the "A" component is usually the "active" portion, and the "B" component is usually the "binding" portion.[2][3] The "A" subunit possesses enzyme activity, and is transferred to the host cell following a conformational change in the membrane-bound transport "B" subunit.[4] These proteins consist of two independent polypeptides, which correspond to the A/B subunit moieties. The enzyme component (A) enters the cell through endosomes produced by the oligomeric binding/translocation protein (B), and prevents actin polymerisation through ADP-ribosylation of monomeric G-actin.[4][5][6]

Examples of the "A" component of an AB toxin include C. perfringens iota toxin Ia,[4] C. botulinum C2 toxin CI,[5] and Clostridium difficile ADP-ribosyltransferase.[6] Other homologous proteins have been found in Clostridium spiroforme.[5][6]

An example of the B component of an AB toxin is Bacillus anthracis protective antigen (PA) protein,[4] B. anthracis secretes three toxin factors: the protective antigen (PA); the oedema factor (EF); and the lethal factor (LF). Each is a thermolabile protein of ~80kDa. PA forms the "B" part of the exotoxin and allows passage of the "A" moiety (consisting of EF or LF) into target cells. PA protein forms the central part of the complete anthrax toxin, and translocates the A moiety into host cells after assembling as a heptamer in the membrane.[7][8]

The Diphtheria toxin also is an AB toxin. It inhibits protein synthesis in the host cell through phosphorylation of the eukaryotic elongation factor 2, which is an essential component for protein synthesis. The exotoxin A of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is another example of an AB toxin that targets the eukaryotic elongation factor 2.

The AB5 toxins are usually considered a type of AB toxin, characterized by B pentamers. Less commonly, the term "AB toxin" is used to emphasize the monomeric character of the B component.

The two-phase mechanism of action of AB toxins is of particular interest in cancer therapy research. The general idea is to modify the B component of existing toxins to selectively bind to malignant cells. This approach combines results from cancer immunotherapy with the high toxicity of AB toxins, giving raise to a new class of chimeric protein drugs, called immunotoxins.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ Giglio, M.L.; Ituarte, S.; Milesi, V.; Dreon, M.S.; Brola, T.R.; Caramelo, J.; Ip, J.C.H.; Maté, S.; Qiu, J.W.; Otero, L.H.; Heras, H. (August 2020). "Exaptation of two ancient immune proteins into a new dimeric pore-forming toxin in snails". Journal of Structural Biology. 211 (2): 107531. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107531. hdl:11336/143650. PMID 32446810.

- 1 2 "Bacterial Pathogenesis: Bacterial Factors that Damage the Host - Producing Exotoxins - A-B Toxins". Archived from the original on 2010-07-27. Retrieved 2008-12-13.

- ↑ De Haan L, Hirst TR (2004). "Cholera toxin: a paradigm for multi-functional engagement of cellular mechanisms (Review)". Mol. Membr. Biol. 21 (2): 77–92. doi:10.1080/09687680410001663267. PMID 15204437. S2CID 22270979.

- 1 2 3 4 Perelle S, Gibert M, Boquet P, Popoff MR (December 1993). "Characterization of Clostridium perfringens iota-toxin genes and expression in Escherichia coli". Infect. Immun. 61 (12): 5147–56. doi:10.1128/IAI.61.12.5147-5156.1993. PMC 281295. PMID 8225592.

- 1 2 3 Fujii N, Kubota T, Shirakawa S, Kimura K, Ohishi I, Moriishi K, Isogai E, Isogai H (March 1996). "Characterization of component-I gene of botulinum C2 toxin and PCR detection of its gene in clostridial species". Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 220 (2): 353–9. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1996.0409. PMID 8645309.

- 1 2 3 Stubbs S, Rupnik M, Gibert M, Brazier J, Duerden B, Popoff M (May 2000). "Production of actin-specific ADP-ribosyltransferase (binary toxin) by strains of Clostridium difficile". FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 186 (2): 307–12. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09122.x. PMID 10802189.

- ↑ Pezard C, Berche P, Mock M (October 1991). "Contribution of individual toxin components to virulence of Bacillus anthracis". Infect. Immun. 59 (10): 3472–7. doi:10.1128/IAI.59.10.3472-3477.1991. PMC 258908. PMID 1910002.

- ↑ Welkos SL, Lowe JR, Eden-McCutchan F, Vodkin M, Leppla SH, Schmidt JJ (September 1988). "Sequence and analysis of the DNA encoding protective antigen of Bacillus anthracis". Gene. 69 (2): 287–300. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(88)90439-8. PMID 3148491. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017.

- ↑ Zahaf N, Schmidt G (2017-07-18). "Bacterial Toxins for Cancer Therapy". Toxins (Basel). 9 (8): 236. doi:10.3390/toxins9080236. PMC 5577570. PMID 28788054.