Abu Rayhan al-Biruni | |

|---|---|

ابوریحان محمد بن احمد البیرونی | |

An imaginary rendition of Al Biruni on a 1973 Soviet postage stamp | |

| Personal | |

| Born | 973 |

| Died | c. 1050 (aged 77) |

| Religion | Islam |

| Era | Islamic Golden Age |

| Region | Khwarezm, Central Asia Ziyarid dynasty (Rey)[1] Ghaznavid dynasty (Ghazni)[2] |

| Denomination | Sunni[3] |

| Creed | Ashari[3][4] |

| Main interest(s) | Geology, physics, anthropology, comparative sociology, astronomy, chemistry, history, geography, mathematics, medicine, psychology, philosophy, theology |

| Notable work(s) | The Remaining Signs of Past Centuries, Gems, Indica, The Mas'udi Canon, Understanding Astrology |

| Muslim leader | |

Influenced by | |

Influenced | |

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni /ælbɪˈruːni/ (Persian: ابوریحان بیرونی; Arabic: أبو الريحان البيروني) (973 – after 1050),[5] known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Comparative Religion", "Father of modern geodesy", and the first anthropologist.[6]

Al-Biruni was well versed in physics, mathematics, astronomy, and natural sciences, and also distinguished himself as a historian, chronologist, and linguist. He studied almost all the sciences of his day and was rewarded abundantly for his tireless research in many fields of knowledge.[7] Royalty and other powerful elements in society funded al-Biruni's research and sought him out with specific projects in mind. Influential in his own right, Al-Biruni was himself influenced by the scholars of other nations, such as the Greeks, from whom he took inspiration when he turned to the study of philosophy. A gifted linguist, he was conversant in Khwarezmian, Persian, Arabic, Sanskrit, and also knew Greek, Hebrew, and Syriac. He spent much of his life in Ghazni, then capital of the Ghaznavids, in modern-day central-eastern Afghanistan. In 1017, he travelled to the Indian subcontinent and wrote a treatise on Indian culture entitled Tārīkh al-Hind ("The History of India"), after exploring the Hindu faith practiced in India.[lower-alpha 1] He was, for his time, an admirably impartial writer on the customs and creeds of various nations, his scholarly objectivity earning him the title al-Ustadh ("The Master") in recognition of his remarkable description of early 11th-century India.

Name

Al-Biruni's name is derived from the Persian word bērūn or bīrūn ("outskirts"), as he was born in an outlying district of Kath, the capital of the Afrighid kingdom of Khwarazm.[5] The city, now called Beruniy, is part of the autonomous republic of Karakalpakstan in northwest Uzbekistan.[9]

Life

Al-Biruni spent the first twenty-five years of his life in Khwarezm where he studied Islamic jurisprudence, theology, grammar, mathematics, astronomy, medicine and philosophy and dabbled not only in the field of physics, but also in those of most of the other sciences. The Iranian Khwarezmian language, which was Biruni's mother tongue,[10][11] survived for several centuries after Islam until the Turkification of the region – at least some of the culture of ancient Khwarezm endured – for it is hard to imagine that the commanding figure of Biruni, a repository of so much knowledge, should have appeared in a cultural vacuum. He was sympathetic to the Afrighids, who were overthrown by the rival dynasty of Ma'munids in 995. He left his homeland for Bukhara, then under the Samanid ruler Mansur II the son of Nuh II. There he corresponded with Avicenna,[12] and there are extant exchanges of views between these two scholars.

In 998, he went to the court of the Ziyarid amir of Tabaristan, Qabus (r. 977–981, 997–1012). There he wrote his first important work, al-Athar al-Baqqiya 'an al-Qorun al-Khaliyya ("The remaining traces of past centuries", translated as "Chronology of ancient nations" or "Vestiges of the Past") on historical and scientific chronology, probably around 1000, though he later made some amendments to the book. He also visited the court of the Bavandid ruler Al-Marzuban. Accepting the definite demise of the Afrighids at the hands of the Ma'munids, he made peace with the latter who then ruled Khwarezm. Their court at Gorganj (also in Khwarezm) was gaining fame for its gathering of brilliant scientists.

In 1017, Mahmud of Ghazni took Rey. Most scholars, including al-Biruni, were taken to Ghazni, the capital of the Ghaznavid dynasty.[1] Biruni was made court astrologer[13] and accompanied Mahmud on his invasions into India, living there for a few years. He was 44 when he went on the journeys with Mahmud of Ghazni.[14] Biruni became acquainted with all things related to India. During this time he wrote his study of India, finishing it around 1030.[15] Along with his writing, Al-Biruni also made sure to extend his study to science while on the expeditions. He sought to find a method to measure the height of the sun, and created a makeshift quadrant for that purpose.[14] Al-Biruni was able to make much progress in his study over the frequent travels that he went on throughout the lands of India.[16]

Belonging to the Sunni Ash'ari school,[3][4] al-Biruni nevertheless also associated with Maturidi theologians. He was however, very critical of the Mu'tazila, particularly criticising al-Jahiz and Zurqan.[17] He also repudiated Avicenna for his views on the eternality of the universe.[18]

Astronomy

Of the 146 books written by al-Bīrūnī, 95 are devoted to astronomy, mathematics, and related subjects like mathematical geography.[19] He lived during the Islamic Golden Age, when the Abbasid Caliphs promoted astronomical research,[14] because such research possessed not only a scientific but also a religious dimension: in Islam worship and prayer require a knowledge of the precise directions of sacred locations, which can be determined accurately only through the use of astronomical data.[14]

In carrying out his research, al-Biruni used a variety of different techniques dependent upon the particular field of study involved.

His major work on astrology is primarily an astronomical and mathematical text; he states: "I have begun with Geometry and proceeded to Arithmetic and the Science of Numbers, then to the structure of the Universe and finally to Judicial Astrology [sic], for no one who is worthy of the style and title of Astrologer [sic] who is not thoroughly conversant with these for sciences." In these earlier chapters he lays the foundations for the final chapter, on astrological prognostication, which he criticises. He was the first to make the semantic distinction between astronomy and astrology,[20] and, in a later work, wrote a refutation of astrology, in contradistinction to the legitimate science of astronomy, for which he expresses wholehearted support. Some suggest that his reasons for refuting astrology relate to the methods used by astrologers being based upon pseudoscience rather than empiricism and also to a conflict between the views of the astrologers and those of the orthodox theologians of Sunni Islam.[21][22]

He wrote an extensive commentary on Indian astronomy in the Taḥqīq mā li-l-Hind mostly translation of Aryabhatta's work, in which he claims to have resolved the matter of Earth's rotation in a work on astronomy that is no longer extant, his Miftah-ilm-alhai'a ("Key to Astronomy"):[23]

[T]he rotation of the earth does in no way impair the value of astronomy, as all appearances of an astronomic character can quite as well be explained according to this theory as to the other. There are, however, other reasons which make it impossible. This question is most difficult to solve. The most prominent of both modern and ancient astronomers have deeply studied the question of the moving of the earth, and tried to refute it. We, too, have composed a book on the subject called Miftah-ilm-alhai'a (Key to Astronomy), in which we think we have surpassed our predecessors, if not in the words, at all events in the matter.

In his description of Sijzi's astrolabe he hints at contemporary debates about the movement of the Earth. He carried on a lengthy correspondence and sometimes heated debate with Ibn Sina, in which Biruni repeatedly attacks Aristotle's celestial physics: he argues by simple experiment that the vacuum state must exist;[18] he is "amazed" by the weakness of Aristotle's argument against elliptical orbits on the basis that they would create a vacuum;[18] he attacks the immutability of the celestial spheres.[18]

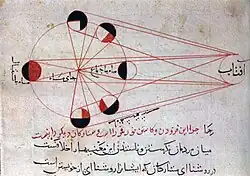

In his major astronomical work, the Mas'ud Canon, Biruni observed that, contrary to Ptolemy, the Sun's apogee (highest point in the heavens) was mobile, not fixed.[24] He wrote a treatise on the astrolabe, describing how to use it to tell the time and as a quadrant for surveying. One particular diagram of an eight-geared device could be considered an ancestor of later Muslim astrolabes and clocks.[14] More recently, Biruni's eclipse data was used by Dunthorne in 1749 to help determine the acceleration of the moon, and his data on equinox times and eclipses was used as part of a study of Earth's past rotation.[25]

Refutation of Eternal Universe

Like later adherents of the Ash'ari school, such as al-Ghazali, al-Biruni is famous for vehemently defending[26] the majority Sunni position that the universe had a beginning, being a strong supporter of creatio ex nihilo, specifically refuting the philosopher Avicenna in a multiple letter correspondence.[18][27] Al-Biruni stated:[28]

"Other people, besides, hold this foolish persuasion, that time has no terminus quo at all."

He further stated that Aristotle, whose arguments Avicenna uses, contradicted himself when he stated that the universe and matter has a start whilst holding on to the idea that matter is pre-eternal. In his letters to Avicenna, he stated the argument of Aristotle, that there is a change in the creator. He further argued that stating there is a change in the creator would mean there is a change in the effect (meaning the universe has change) and that the universe coming into being after not being is such a change (and so arguing there is no change – no beginning – means Aristotle believes the creator is negated).[18] Al-Biruni was proud of the fact that he followed the textual evidence of the religion without being influenced by Greek philosophers such as Aristotle.[18]

Physics

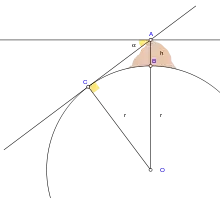

Al-Biruni contributed to the introduction of the scientific method to medieval mechanics.[29][30] He developed experimental methods to determine density, using a particular type of hydrostatic balance.[14] Al-Biruni's method of using the hydrostatic balance was precise, and he was able to measure the density of many different substances, including precious metals, gems, and even air. He also used this method to determine the radius of the earth, which he did by measuring the angle of elevation of the horizon from the top of a mountain and comparing it to the angle of elevation of the horizon from a nearby plain.

In addition to developing the hydrostatic balance, Al-Biruni also wrote extensively on the topic of density, including the different types of densities and how they are measured. His work on the subject was very influential and was later used by scientists like Galileo and Newton in their own research.[31]

Geography and geodesy

Bīrūnī devised a novel method of determining the Earth's radius by means of the observation of the height of a mountain. He carried it out at Nandana in Pind Dadan Khan (present-day Pakistan).[32] He used trigonometry to calculate the radius of the Earth using measurements of the height of a hill and measurement of the dip in the horizon from the top of that hill. His calculated radius for the Earth of 3928.77 miles was 2% higher than the actual mean radius of 3847.80 miles.[14] His estimate was given as 12,803,337 cubits, so the accuracy of his estimate compared to the modern value depends on what conversion is used for cubits. The exact length of a cubit is not clear; with an 18-inch cubit his estimate would be 3,600 miles, whereas with a 22-inch cubit his estimate would be 4,200 miles.[33] One significant problem with this approach is that Al-Biruni was not aware of atmospheric refraction and made no allowance for it. He used a dip angle of 34 arc minutes in his calculations, but refraction can typically alter the measured dip angle by about 1/6, making his calculation only accurate to within about 20% of the true value.[34]

In his Codex Masudicus (1037), Al-Biruni theorized the existence of a landmass along the vast ocean between Asia and Europe, or what is today known as the Americas. He argued for its existence on the basis of his accurate estimations of the Earth's circumference and Afro-Eurasia's size, which he found spanned only two-fifths of the Earth's circumference, reasoning that the geological processes that gave rise to Eurasia must surely have given rise to lands in the vast ocean between Asia and Europe. He also theorized that at least some of the unknown landmass would lie within the known latitudes which humans could inhabit, and therefore would be inhabited.[35]

Pharmacology and mineralogy

Biruni wrote a pharmacopoeia, the Kitab al-saydala fi al-tibb ("Book on the Pharmacopoeia of Medicine"). It lists synonyms for drug names in Syriac, Persian, Greek, Baluchi, Afghan, Kurdi, and some Indian languages.[36][37]

He used a hydrostatic balance to determine the density and purity of metals and precious stones. He classified gems by what he considered their primary physical properties, such as specific gravity and hardness, rather than the common practice of the time of classifying them by colour.[38]

History and chronology

Biruni's main essay on political history, Kitāb al-musāmara fī aḵbār Ḵᵛārazm ("Book of nightly conversation concerning the affairs of Ḵᵛārazm") is now known only from quotations in Bayhaqī's Tārīkh-e Masʿūdī. In addition to this various discussions of historical events and methodology are found in connection with the lists of kings in his al-Āthār al-bāqiya and in the Qānūn as well as elsewhere in the Āthār, in India, and scattered throughout his other works.[39] Al-Biruni's Chronology of Ancient Nations attempted to accurately establish the length of various historical eras.[14]

History of religions

Biruni is widely considered to be one of the most important Muslim authorities on the history of religion.[40] He is known as a pioneer in the field of comparative religion in his study of, among other creeds, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Hinduism, Christianity, Buddhism and Islam. He assumed the superiority of Islam: "We have here given an account of these things in order that the reader may learn by the comparative treatment of the subject how much superior the institutions of Islam are, and how more plainly this contrast brings out all customs and usages, differing from those of Islam, in their essential foulness." However he was happy on occasion to express admiration for other cultures, and quoted directly from the sacred texts of other religions when reaching his conclusions. [41] He strove to understand them on their own terms rather than trying to prove them wrong. His underlying concept was that all cultures are at least distant relatives of all other cultures because they are all human constructs. "Rather, what Al-Biruni seems to be arguing is that there is a common human element in every culture that makes all cultures distant relatives, however foreign they might seem to one another."[42]

Al-Biruni divides Hindus into an educated and an uneducated class. He describes the educated as monotheistic, believing that God is one, eternal, and omnipotent and eschewing all forms of idol worship. He recognizes that uneducated Hindus worshiped a multiplicity of idols yet points out that even some Muslims (such as the Jabriyah) have adopted anthropomorphic concepts of God.[43]

Anthropology

Al-Biruni wrote about the peoples, customs and religions of the Indian subcontinent. According to Akbar S. Ahmed, like modern anthropologists, he engaged in extensive participant observation with a given group of people, learnt their language and studied their primary texts, presenting his findings with objectivity and neutrality using cross-cultural comparisons. Akhbar S. Ahmed concluded that Al-Biruni can be considered as the first Anthropologist,[44] others, however, have argued that he can hardly be considered an anthropologist in the conventional sense.[45]

Indology

Al-Biruni's fame as an Indologist rests primarily on two texts.[46] Al-Biruni wrote an encyclopedic work on India called Taḥqīq mā li-l-Hind min maqūlah maqbūlah fī al-ʿaql aw mardhūlah (variously translated as Verifying All That the Indians Recount, the Reasonable and the Unreasonable,[47] or The book confirming what pertains to India, whether rational or despicable,[46] in which he explored nearly every aspect of Indian life. During his journey through India, military and political history were not Al-Biruni's main focus: he decided rather to document the civilian and scholarly aspects of Hindu life, examining culture, science, and religion. He explored religion within a rich cultural context.[16] He expressed his objectives with simple eloquence: He also translated the Yoga sutras of Indian sage Patanjali with the title Tarjamat ketāb Bātanjalī fi’l-ḵalāṣ men al-ertebāk:[48]

I shall not produce the arguments of our antagonists in order to refute such of them, as I believe to be in the wrong. My book is nothing but a simple historic record of facts. I shall place before the reader the theories of the Hindus exactly as they are, and I shall mention in connection with them similar theories of the Greeks in order to show the relationship existing between them.

An example of Al-Biruni's analysis is his summary of why many Hindus hate Muslims. Biruni notes in the beginning of his book how the Muslims had a hard time learning about Hindu knowledge and culture.[16] He explains that Hinduism and Islam are totally different from each other. Moreover, Hindus in 11th century India had suffered waves of destructive attacks on many of its cities, and Islamic armies had taken numerous Hindu slaves to Persia, which – claimed Al-Biruni – contributed to Hindus becoming suspicious of all foreigners, not just Muslims. Hindus considered Muslims violent and impure, and did not want to share anything with them. Over time, Al-Biruni won the welcome of Hindu scholars. Al-Biruni collected books and studied with these Hindu scholars to become fluent in Sanskrit, discover and translate into Arabic the mathematics, science, medicine, astronomy and other fields of arts as practiced in 11th-century India. He was inspired by the arguments offered by Indian scholars who believed earth must be globular in shape, which they felt was the only way to fully explain the difference in daylight hours by latitude, seasons and Earth's relative positions with Moon and stars. At the same time, Al-Biruni was also critical of Indian scribes, who he believed carelessly corrupted Indian documents while making copies of older documents.[49] He also criticized the Hindus on what he saw them do and not do, for example finding them deficient in curiosity about history and religion.[16]

One of the specific aspects of Hindu life that Al-Biruni studied was the Hindu calendar. His scholarship on the topic exhibited great determination and focus, not to mention the excellence in his approach of the in-depth research he performed. He developed a method for converting the dates of the Hindu calendar to the dates of the three different calendars that were common in the Islamic countries of his time period, the Greek, the Arab/Muslim, and the Persian. Biruni also employed astronomy in the determination of his theories, which were complex mathematical equations and scientific calculation that allows one to convert dates and years between the different calendars.[50]

The book does not limit itself to tedious records of battle because Al-Biruni found the social culture to be more important. The work includes research on a vast array of topics of Indian culture, including descriptions of their traditions and customs. Although he tried to stay away from political and military history, Biruni did indeed record important dates and noted actual sites of where significant battles occurred. Additionally, he chronicled stories of Indian rulers and told of how they ruled over their people with their beneficial actions and acted in the interests of the nation. His details are brief and mostly just list rulers without referring to their real names, and he did not go on about deeds that each one carried out during their reign, which keeps in line with Al-Biruni's mission to try to stay away from political histories. Al-Biruni also described the geography of India in his work. He documented different bodies of water and other natural phenomena. These descriptions are useful to today's modern historians because they are able to use Biruni's scholarship to locate certain destinations in modern-day India. Historians are able to make some matches while also concluding that certain areas seem to have disappeared and been replaced with different cities. Different forts and landmarks were able to be located, legitimizing Al-Biruni's contributions with their usefulness to even modern history and archeology.[16]

The dispassionate account of Hinduism given by Al-Biruni was remarkable for its time. He stated that he was fully objective in his writings, remaining unbiased like a proper historian should. Biruni documented everything about India just as it happened. But, he did note how some of the accounts of information that he was given by natives of the land may not have been reliable in terms of complete accuracy, however, he did try to be as honest as possible in his writing.[16] Edward C. Sachau compares it to "a magic island of quiet, impartial research in the midst of a world of clashing swords, burning towns, and plundered temples."[51] Biruni's writing was very poetic, which may diminish some of the historical value of the work for modern times. The lack of description of battle and politics makes those parts of the picture completely lost. However, Many have used Al-Biruni's work to check facts of history in other works that may have been ambiguous or had their validity questioned.[16]

Works

Most of the works of Al-Biruni are in Arabic although he seemingly wrote the Kitab al-Tafhim in both Persian and Arabic, showing his mastery over both languages.[52] Bīrūnī's catalogue of his own literary production up to his 65th lunar/63rd solar year (the end of 427/1036) lists 103 titles divided into 12 categories: astronomy, mathematical geography, mathematics, astrological aspects and transits, astronomical instruments, chronology, comets, an untitled category, astrology, anecdotes, religion, and books he no longer possesses.[53]

Selection of extant works

- Taḥqīq mā li-l-Hind (A Critical Study of What India Says, Whether Accepted by Reason or Refused; تحقيق ما للهند من مقولة معقولة في العقل أو مرذولة), popularly called Kitāb al-Hind (The Book on India);[54] English translations called Indica or Alberuni's India. The work is a compendium of India's religion and philosophy.[28]

- Kitab al-tafhim li-awa’il sina‘at al-tanjim (Book of Instruction in the Elements of the Art of Astrology); in Persian.

- The Remaining Signs of Past Centuries (الآثار الباقية عن القرون الخالية), a comparative study of calendars of cultures and civilizations, (including several chapters on Christian cults), which contains mathematical, astronomical, and historical information.

- The Mas'udi Law (قانون مسعودي), an encyclopaedia of astronomy, geography, and engineering, dedicated to Mas'ud, son of the Ghaznavid sultan Mahmud of Ghazni.

- Understanding Astrology (التفهيم لصناعة التنجيم), a question and answer style book about mathematics and astronomy, in Arabic and Persian.

- Pharmacy, a work on drugs and medicines.

- Gems (الجماهر في معرفة الجواهر), a geology manual about minerals and gems. Dedicated to Mawdud, son of Mas'ud.

- A history of Mahmud of Ghazni and his father

- A history of Khawarezm

- Kitab al-Āthār al-Bāqīyah ‘an al-Qurūn al-Khālīyah.[28]

- Risālah li-al-Bīrūnī (Epître de Berūnī)[55]

Persian work

Biruni wrote most of his works in Arabic, the scientific language of his age, but al-Tafhim is one of the most important of the early works of science in Persian, and is a rich source for Persian prose and lexicography. The book covers the Quadrivium in a detailed and skilled fashion.[52]

Legacy

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Following Al-Biruni's death, his work was neither built upon or referenced by scholars. Centuries later, his writings about India, which had become of interest to the British Raj, were revisited.[56]

The lunar crater Al-Biruni and the asteroid 9936 Al-Biruni are named in his honour. Biruni Island in Antarctica is named after al-Biruni. In Iran, surveying engineers are celebrated on al-Biruni's birthday.

In June 2009, Iran donated a pavilion to the United Nations Office in Vienna—placed in the central Memorial Plaza of the Vienna International Center.[57] Named the Scholars Pavilion, it features the statues of four prominent Iranian scholars: Avicenna, Abu Rayhan Biruni, Zakariya Razi (Rhazes) and Omar Khayyam.[58]

In popular culture

A film about the life of Al-Biruni, Abu Raykhan Beruni, was released in the Soviet Union in 1974.[59]

Irrfan Khan portrayed Al-Biruni in the 1988 Doordarshan historical drama Bharat Ek Khoj. He has been portrayed by Cüneyt Uzunlar in the Turkish television series Alparslan: Büyük Selçuklu on TRT 1.

Notes

References

- 1 2 Kennedy 1975, p. 394.

- ↑ Ataman 2008, p. 58.

- 1 2 3 Akhtar 2011.

- 1 2 Kaminski 2017.

- 1 2 Bosworth 2000.

- ↑ Ahmed 1984, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Yano 2013.

- ↑ Verdon 2015, p. 52.

- ↑ Gulyamova 2022, p. 42.

- ↑ Strohmaier 2006, p. 112.

- ↑ MacKenzie 2000.

- ↑ Papan-Matin 2010, p. 111.

- ↑ Hodgson 1974, p. 68.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sparavigna 2013.

- ↑ Waardenburg 1999, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Khan 1976.

- ↑ Watt & Said 1979, pp. 414–419.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Berjak & Muzaffar 2003.

- ↑ Saliba 2000.

- ↑ Pines 1964.

- ↑ Saliba 1982, pp. 248–251.

- ↑ Noonan 2005, p. 32.

- ↑ al-Biruni & Sachau 1910, p. 277.

- ↑ Covington 2007.

- ↑ Stephenson 2008, pp. 45, 457, 491–493.

- ↑ Nasr 1993.

- ↑ Vibert 1973.

- 1 2 3 al-Biruni & Sachau 1910.

- ↑ Alikuzai 2013, p. 154.

- ↑ Rozhanskaya & Levinova 1996.

- ↑ Hannam 2009.

- ↑ Pingree 2000b.

- ↑ Vibert 1973, p. 211.

- ↑ Huth 2013, pp. 216–217.

- ↑ Scheppler 2006.

- ↑ Kujundzić & Masić 1999.

- ↑ Levey 1973, p. 145.

- ↑ Anawati 2000.

- ↑ Pingree 2000c.

- ↑ de Blois 2000.

- ↑ Kamaruzzaman 2003.

- ↑ Ataman 2008, p. 60.

- ↑ Ataman 2005.

- ↑ Ahmed 1984.

- ↑ Tapper 1995.

- 1 2 Lawrence 2000.

- ↑ George Saliba. "Al-Bīrūnī". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ↑ al-Biruni & Sachau 1910, p. 5.

- ↑ al-Biruni & Sachau 1910, p. 17.

- ↑ Kennedy, Engle & Wamstad 1965.

- ↑ al-Biruni & Sachau 1910, p. 26.

- 1 2 Nasr 1993, p. 111.

- ↑ Pingree 2000a.

- ↑ Verdon 2015, p. 37.

- ↑ Kraus 1936.

- ↑ "Al-Biruni" (Radio broadcast). In Our Time. BBC. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ↑ "Monument to Be Inaugurated at the Vienna International Centre, 'Scholars Pavilion' donated to International Organizations in Vienna by Iran". United Nations Information Service Vienna. 5 June 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ↑ "Permanent mission of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the United Nations office – Vienna". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ↑ Abbasov, Shukhrat; Saidkasymov, Pulat; Shukurov, Bakhtiyer; Khamrayev, Razak (14 April 1975). "Abu Raykhan Beruni". IMDb. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

Sources

- Ahmed, Akbar S. (1984). "Al-Beruni: The First Anthropologist". RAIN. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland (60): 9–10. doi:10.2307/3033407. JSTOR 3033407.

- Akhtar, Zia (2011). "Constitutional legitimacy: Sharia law, secularism and the social compact". Indonesia Law Review. 2 (1): 107–127. doi:10.15742/ilrev.v1n2.84. S2CID 153637958.

- Alikuzai, Hamid Wahed (2013). A Concise History of Afghanistan in 25 Volumes. Vol. 1. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4907-1446-2.

- Anawati, Georges C. (2000). "Bīrūnī, Abū Rayḥān v. Pharmacology and Mineralogy". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Ataman, Kemal (2005). "Re-Reading al-Biruni's India: a Case for Intercultural Understanding". Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations. Routledge. 16 (2): 141–154. doi:10.1080/09596410500059623. S2CID 143545645.

- Ataman, Kemal (2008). Understanding Other Religions: Al-Biruni's and Gadamer's "Fusion of Horizons". Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change. Washington, D.C.: The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy. ISBN 978-1-56518-252-3.

- Berjak, Rafik; Muzaffar, Iqbal (2003). "Ibn Sina--Al-Biruni correspondence". Islam & Science. 1 (1): 91 – via Gale Academic OneFile.

- al-Biruni; Sachau, Eduard (1910). Sachau, Eduard (ed.). Alberuni's India: An Account of the Religion, Philosophy, Literature, Geography, Chronology, Astronomy, Customs, Laws and Astrology of India about A.D. 1030. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. OCLC 1039522051.(volume 1; volume 2)

- de Blois, François (2000). "Bīrūnī, Abū Rayḥān: vii. History of Religion". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Bosworth, C. Edmund (2000). "Bīrūnī, Abū Rayḥān". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Covington, Richard (2007). "Rediscovering Arabic Science". Aramco World. Vol. 58, no. 3. Retrieved 6 March 2023.>

- Gulyamova, Lola (2022). The Geography of Uzbekistan: At the Crossroads of the Silk Road. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-30310-7-873-6.

- Hannam, James (2009). God's Philosophers: How the Medieval World Laid the Foundations of Modern Science. London: Icon. ISBN 978-1-84831-150-3.

- Hodgson, Marshall G. S. (1974). The Venture of Islam: Conscience and History in a World Civilization. Vol. 2: The Expansion of Islam in the Middle Periods. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-34677-9.

- Huth, John Edward (2013). The Lost Art of Finding Our Way. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-07282-4.

- Levey, Martin (1973). Early Arabic Pharmacology: An Introduction Based on Ancient and Medieval Sources. Brill Archive. ISBN 978-90-04-03796-0.

- Kamaruzzaman, Kamar Oniah (2003). "Al-Biruni: Father of Comparative Religion". Intellectual Discourse. 11 (2).

- Kaminski, Joseph J. (2017). The Contemporary Islamic Governed State: A Reconceptualization. Palgrave Series in Islamic Theology, Law, and History. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 31–70. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-57012-9_2. ISBN 978-33195-7-011-2.

- Kennedy, E.S.; Engle, Susan; Wamstad, Jeanne (1965). "The Hindu Calendar as Described in Al-Biruni's Masudic Canon". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 24 (3): 274–284. doi:10.1086/371821. S2CID 161208100.

- Kennedy, Edward Stewart (1975). "The Exact Sciences". In Frye, R. N.; Fisher, William Bayne (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20093-6.

- Khan, M.S. (1976). "Al-Biruni and the Political History of India". Oriens. 25/26: 86–115. doi:10.1163/18778372-02502601007. ISSN 0078-6527.

- Kraus, Paul, ed. (1936). Epître de Beruni contenant le répertoire des ouvrages de Muhammad b. Zakariya ar-Razi (in French). Paris: J.P. Maisonneuve. OCLC 1340409059.

- Kujundzić, E.; Masić, I. (1999). "Al-Biruni—a universal scientist". Medical Archives (in Croatian). 53 (2): 117–120. PMID 10386051.

- Lawrence, Bruce B. (2000). "Bīrūnī, Abū Rayḥān: viii. Indology". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- MacKenzie, D. N. (2000). "Chorasmia: iii. The Chorasmian Language". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (1993). An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines: Conceptions of Nature and Methods used for its Study by the Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ, al-Bīrūnī, and Ibn Sīnā" (2nd ed.). Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-07914-1-515-3.

- Noonan, George C. (2005). Classical Scientific Astrology. Tempe, Arizona: American Federation of Astrologers. ISBN 978-0-86690-049-2.

- Papan-Matin, Firoozeh (2010). Beyond Death: The Mystical Teachings of ʻAyn Al-Quḍāt Al-Hamadhānī. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-17413-9.

- Pines, S. (1964). "The Semantic Distinction between the Terms Astronomy and Astrology according to al-Biruni". Isis. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. 55 (3): 343–349. doi:10.1086/349868. ISSN 1545-6994. JSTOR 228577. S2CID 143941055 – via JSTOR.

- Pingree, David (2000a). "Bīrūnī, Abū Rayḥān: ii. Bibliography". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Pingree, David (2000b). "Bīrūnī, Abū Rayḥān: iv. Geography". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Pingree, David (2000c). "Bīrūnī, Abū Rayḥān: vi. History and Chronology". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Rozhanskaya, Mariam; Levinova, I. S. (1996). "Statics". In Rushdī, Rāshid (ed.). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. Psychology Press. pp. 274–298. ISBN 978-0-415-12411-9.

- Saliba, George (1982). "Al-Biruni". In Strayer, Joseph (ed.). Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-06841-9-073-0.

- Saliba, George (2000). "Bīrūnī, Abū Rayḥān:iii. Mathematics and Astronomy". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Scheppler, Bill (2006). Al-Biruni: Master Astronomer and Muslim Scholar of the Eleventh Century. Great Muslim Philosophers and Scientists of the Middle Ages. New York: Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4042-0512-3.

- Sparavigna, Amelia (2013). "The Science of Al-Biruni". International Journal of Sciences. 2 (12): 52–60. arXiv:1312.7288. doi:10.18483/ijSci.364. S2CID 119230163.

- Stephenson, F. Richard (2008) [1997]. Historical Eclipses and Earth's Rotation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-05633-5.

- Strohmaier, Gotthard (2006). "Biruni". In Meri, Josef W. (ed.). Medieval Islamic Civilization: A-K, index. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-96691-7.

- Tapper, Richard (1995). ""Islamic Anthropology" and the "Anthropology of Islam"". Anthropological Quarterly. 68 (3): 185–193. doi:10.2307/3318074. ISSN 0003-5491. JSTOR 3318074.

- Vibert, Douglas A. (1973). "Al-Biruni, Persian Scholar, 973–1048". Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 67: 209–211. Bibcode:1973JRASC..67..209D. ISSN 0035-872X.

- Verdon, Noémie (2015). "Cartography and Cultural Identity: Conceptualisation of al-Hind by Arabic and Persian writers". In Ray, Himanshu Prabha (ed.). Negotiating Cultural Identity: Landscapes in Early Medieval South Asian History. Archaeology and Religion in South Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-34130-7.

- Waardenburg, Jacques, ed. (1999). Muslim Perceptions of Other Religions: A Historical Survey. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-535576-5.

- Watt, William Montgomery; Said, Hakim M. (1979). Al-Bīrūnī and the Study of Non-Islamic Religions. OCLC 278693104.

- Yano, Michio (2013). "al-Bīrūnī". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

Further reading

- Ali, Wahshat Khan Bahadur Reza (1951). Al-Biruni Commemoration Volume. Calcutta: Iran Society. OCLC 55570787.

- Bosworth, C. E. (1968). "The Political and Dynastic History of the Iranian World (A.D. 1000–1217)". In Boyle, J.A. (ed.). The Saljuq and Mongol Periods. The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 5. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521069366. OCLC 1015426101.

- Brockelmann, C (1987) [1913–1938]. "al-Biruni". In Houtsma, M. T.; Arnold, T.W.; Basset, R.; Hartmann, R. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Vol. 2 (1st ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/2214-871X_ei1_SIM_1392. ISBN 978-90-04-08265-6.

- Elliot, Henry Miers; Dowson, John (1871). "1. Táríkhu-l Hind of Bírúní". The History of India, as told by Its own Historians. Vol. 2: The Muhammadan Period. London: Trübner & Co. OCLC 76070790.

- Ghorbani, Abolghassem (1974). Bīrūnī nāmeh [A monograph on Abu Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī]. Tehran: Iranian National Heritage Society Press. OCLC 1356523019. (Includes facsimile edition of the Arabic text of al-Biruni's Maqālīd 'ilm al-hay'a ("Keys of Astronomy"))

- Glick, Thomas F.; Livesey, Steven John; Wallis, Faith (2005). Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96930-7.

- Karamati, Younes; Melvin-Koushki, Matthew (2021). "al-Bīrūnī". In Madelung, Wilferd; Daftary, Farhad (eds.). Encyclopaedia Islamica Online. Brill Online. ISSN 1875-9831.

- Kennedy, E.S. (1970). "Al-Biruni". In Gillispie, Charles Coulston; Holmes, Frederic Lawrence (eds.). Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Vol. 2. New York: Scribner. pp. 147–157. ISBN 9780684101149. OCLC 755137603.

- Kiple, Kenneth F.; Ornelas, Kriemhild Coneè (2001). The Cambridge World History of Food. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-40216-3.

- Naba’i, Abulfadl (2019) [2002]. Calendar-Making in the History. Astan Quds Razavi Publishing Co. ISBN 978-600-02-0665-9.

- Rashed, Roshdi; Morelon, Régis (2019). Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-12410-2.

- Saliba, George (1994). A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-8023-7.

- Samian, A.L. (2011). "Reason and Spirit in Al-Biruni's Philosophy of Mathematics". In Tymieniecka, A-T. (ed.). Reason, Spirit and the Sacral in the New Enlightenment. Islamic Philosophy and Occidental Phenomenology in Dialogue. Vol. 5. Netherlands: Springer. pp. 137–146. doi:10.1007/978-90-481-9612-8_9. ISBN 978-90-481-9612-8.

- Wilczynski, Jan Z. (1959). "On the Presumed Darwinism of Alberuni Eight Hundred Years before Darwin". Isis. 50 (4): 459–466. doi:10.1086/348801. JSTOR 226430. S2CID 143086988.

- Yano, Michio (2007). "Bīrūnī: Abū al‐Rayḥān Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al‐Bīrūnī". In Hockey, Thomas; et al. (eds.). Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer Publishers. pp. 131–133. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-30400-7_1433. ISBN 978-1-4419-9918-4. (PDF version)

- Yasin, Mohammed (1975). "Al-Biruni in India". Islamic Culture. 49: 207–213 – via Internet Archive.

External links

- The works of Abu Rayhan (al-)Biruni – manuscripts, critical editions, and translations compiled by Jan Hogendijk

- Digitized facsimiles of works by al-Biruni at the British Library: