| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /əˈkæmproʊseɪt/ |

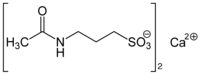

| Trade names | Campral EC |

| Other names | N-Acetyl homotaurine, Acamprosate calcium (JAN JP), Acamprosate calcium (USAN US) |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral[1] |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 11%[1] |

| Protein binding | Negligible[1] |

| Metabolism | Nil[1] |

| Elimination half-life | 20 h to 33 h[1] |

| Excretion | Kidney[1] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.071.495 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

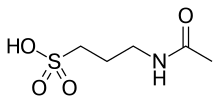

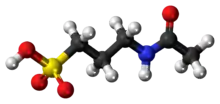

| Formula | C5H11NO4S |

| Molar mass | 181.21 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Acamprosate, sold under the brand name Campral, is a medication used along with counseling to treat alcohol use disorder.[1][2]

Acamprosate is thought to stabilize chemical signaling in the brain that would otherwise be disrupted by alcohol withdrawal.[3] When used alone, acamprosate is not an effective therapy for alcohol use disorder in most individuals;[4] studies have found that acamprosate works best when used in combination with psychosocial support since the drug facilitates a reduction in alcohol consumption as well as full abstinence.[2][5][6]

Serious side effects include allergic reactions, abnormal heart rhythms, and low or high blood pressure, while less serious side effects include headaches, insomnia, and impotence.[7] Diarrhea is the most common side-effect.[8] It is unclear if use is safe during pregnancy.[9][10]

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[11]

Medical uses

Acamprosate is useful when used along with counseling in the treatment of alcohol use disorder.[2] Over three to twelve months it increases the number of people who do not drink at all and the number of days without alcohol.[2] It appears to work as well as naltrexone for maintenance of abstinence from alcohol,[12] however naltrexone works slightly better for reducing alcohol cravings and heavy drinking,[13] and acamprosate tends to work more poorly outside of Europe where treatment services are less robust.[14]

Contraindications

Acamprosate is primarily removed by the kidneys. A dose reduction is suggested in those with moderately impaired kidneys (creatinine clearance between 30 mL/min and 50 mL/min).[1][15] It is also contraindicated in those who have a strong allergic reaction to acamprosate calcium or any of its components.[15]

Adverse effects

The US label carries warnings about increases of suicidal behavior, major depressive disorder, and kidney failure.[1]

Adverse effects that caused people to stop taking the drug in clinical trials included diarrhea, nausea, depression, and anxiety.[1]

Potential adverse effects include headache, stomach pain, back pain, muscle pain, joint pain, chest pain, infections, flu-like symptoms, chills, heart palpitations, high blood pressure, fainting, vomiting, upset stomach, constipation, increased appetite, weight gain, edema, sleepiness, decreased sex drive, impotence, forgetfulness, abnormal thinking, abnormal vision, distorted sense of taste, tremors, runny nose, coughing, difficulty breathing, sore throat, bronchitis, and rashes.[1]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

The pharmacodynamics of acamprosate are complex and not fully understood;[16][17][18] however, it is believed to act as an NMDA receptor antagonist and positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors.[17][18]

Its activity on those receptors is indirect, unlike that of most other agents used in this context.[19] An inhibition of the GABA-B system is believed to cause indirect enhancement of GABAA receptors.[19] The effects on the NMDA complex are dose-dependent; the product appears to enhance receptor activation at low concentrations, while inhibiting it when consumed in higher amounts, which counters the excessive activation of NMDA receptors in the context of alcohol withdrawal.[20]

The product also increases the endogenous production of taurine.[20]

Ethanol and benzodiazepines act on the central nervous system by binding to the GABAA receptor, increasing the effects of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA (i.e., they act as positive allosteric modulators at these receptors).[17][4] In alcohol use disorder, one of the main mechanisms of tolerance is attributed to GABAA receptors becoming downregulated (i.e. these receptors become less sensitive to GABA).[4] When alcohol is no longer consumed, these down-regulated GABAA receptor complexes are so insensitive to GABA that the typical amount of GABA produced has little effect, leading to physical withdrawal symptoms;[4] since GABA normally inhibits neural firing, GABAA receptor desensitization results in unopposed excitatory neurotransmission (i.e., fewer inhibitory postsynaptic potentials occur through GABAA receptors), leading to neuronal over-excitation (i.e., more action potentials in the postsynaptic neuron). One of acamprosate's mechanisms of action is the enhancement of GABA signaling at GABAA receptors via positive allosteric receptor modulation.[17][18] It has been purported to open the chloride ion channel in a novel way as it does not require GABA as a cofactor, making it less liable for dependence than benzodiazepines. Acamprosate has been successfully used to control tinnitus, hyperacusis, ear pain, and inner ear pressure during alcohol use due to spasms of the tensor tympani muscle.

In addition, alcohol also inhibits the activity of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs).[21][22] Chronic alcohol consumption leads to the overproduction (upregulation) of these receptors. Thereafter, sudden alcohol abstinence causes the excessive numbers of NMDARs to be more active than normal and to contribute to the symptoms of delirium tremens and excitotoxic neuronal death.[23] Withdrawal from alcohol induces a surge in release of excitatory neurotransmitters like glutamate, which activates NMDARs.[24] Acamprosate reduces this glutamate surge.[25] The drug also protects cultured cells from excitotoxicity induced by ethanol withdrawal[26] and from glutamate exposure combined with ethanol withdrawal.[27]

The substance also helps re-establish a standard sleep architecture by normalizing stage 3 and REM sleep phases, which is believed to be an important aspect of its pharmacological activity.[20]

Pharmacokinetics

Acamprosate is not metabolized by the human body.[18] Acamprosate's absolute bioavailability from oral administration is approximately 11%,[18] and its bioavailability is decreased when taken with food.[28] Following administration and absorption of acamprosate, it is excreted unchanged (i.e., as acamprosate) via the kidneys.[18]

Its absorption and elimination are very slow, with a Tmax of 6 hours and an elimination half life of over 30 hours.[19]

History

Acamprosate was developed by Lipha, a subsidiary of Merck KGaA.[29] and was approved for marketing in Europe in 1989.

In October 2001 Forest Laboratories acquired the rights to market the drug in the US.[29][30]

It was approved by the FDA in July 2004.[31]

The first generic versions of acamprosate were launched in the US in 2013.[32]

As of 2015 acamprosate was in development by Confluence Pharmaceuticals as a potential treatment for fragile X syndrome. The drug was granted orphan status for this use by the FDA in 2013 and by the EMA in 2014.[33]

Society and culture

"Acamprosate" is the INN and BAN for this substance. "Acamprosate calcium" is the USAN and JAN. It is also technically known as N-acetylhomotaurine or as calcium acetylhomotaurinate.

It is sold under the brand name Campral.[1]

Research

In addition to its apparent ability to help patients refrain from drinking, some evidence suggests that acamprosate is neuroprotective (that is, it protects neurons from damage and death caused by the effects of alcohol withdrawal, and possibly other causes of neurotoxicity).[25][34]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Campral label" (PDF). FDA. January 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2017. For label updates see FDA index page for NDA 021431

- 1 2 3 4 Plosker GL (July 2015). "Acamprosate: A Review of Its Use in Alcohol Dependence". Drugs. 75 (11): 1255–1268. doi:10.1007/s40265-015-0423-9. PMID 26084940. S2CID 19119078.

- ↑ Williams SH (November 2005). "Medications for treating alcohol dependence". American Family Physician. 72 (9): 1775–1780. PMID 16300039. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

- 1 2 3 4 Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE, Holtzman DM (2015). "Chapter 16: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 9780071827706.

It has been hypothesized that long-term ethanol exposure alters the expression or activity of specific GABAA receptor subunits in discrete brain regions. Regardless of the underlying mechanism, ethanol-induced decreases in GABAA receptor sensitivity are believed to contribute to ethanol tolerance, and also may mediate some aspects of physical dependence on ethanol. ... Detoxification from ethanol typically involves the administration of benzodiazepines such as chlordiazepoxide, which exhibit cross-dependence with ethanol at GABAA receptors (Chapters 5 and 15). A dose that will prevent the physical symptoms associated with withdrawal from ethanol, including tachycardia, hypertension, tremor, agitation, and seizures, is given and is slowly tapered. Benzodiazepines are used because they are less reinforcing than ethanol among alcoholics. Moreover, the tapered use of a benzodiazepine with a long half-life makes the emergence of withdrawal symptoms less likely than direct withdrawal from ethanol. ... Unfortunately, acamprosate is not adequately effective for most alcoholics.

- ↑ Mason BJ (2001). "Treatment of alcohol-dependent outpatients with acamprosate: a clinical review". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 62 (Suppl 20): 42–48. PMID 11584875.

- ↑ Nutt DJ, Rehm J (January 2014). "Doing it by numbers: a simple approach to reducing the harms of alcohol". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 28 (1): 3–7. doi:10.1177/0269881113512038. PMID 24399337. S2CID 36860967.

- ↑ "Acamprosate". drugs.com. 2005-03-25. Archived from the original on 22 December 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- ↑ Wilde MI, Wagstaff AJ (June 1997). "Acamprosate. A review of its pharmacology and clinical potential in the management of alcohol dependence after detoxification". Drugs. 53 (6): 1038–1053. doi:10.2165/00003495-199753060-00008. PMID 9179530. S2CID 195691152.

- ↑ "Acamprosate (Campral) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com.

- ↑ Haber P, Lintzeris N, Proude E, Lopatko O. "Guidelines for the Treatment of Alcohol Problems" (PDF). Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ↑ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ↑ Kranzler HR, Soyka M (August 2018). "Diagnosis and Pharmacotherapy of Alcohol Use Disorder: A Review". JAMA. 320 (8): 815–824. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.11406. PMC 7391072. PMID 30167705.

- ↑ Maisel NC, Blodgett JC, Wilbourne PL, Humphreys K, Finney JW (February 2013). "Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful?". Addiction. 108 (2): 275–293. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04054.x. PMC 3970823. PMID 23075288.

- ↑ Donoghue K, Elzerbi C, Saunders R, Whittington C, Pilling S, Drummond C (June 2015). "The efficacy of acamprosate and naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence, Europe versus the rest of the world: a meta-analysis". Addiction. 110 (6): 920–930. doi:10.1111/add.12875. PMID 25664494.

- 1 2 Saivin S, Hulot T, Chabac S, Potgieter A, Durbin P, Houin G (November 1998). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of acamprosate". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 35 (5): 331–345. doi:10.2165/00003088-199835050-00001. PMID 9839087. S2CID 34047050.

- ↑ "Acamprosate: Biological activity". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

Due to the complex nature of this drug's MMOA, and a paucity of well defined target affinity data, we do not map to a primary drug target in this instance.

- 1 2 3 4 "Acamprosate: Summary". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to Pharmacology. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

Acamprosate is a NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist and a positive allosteric modulator of GABAA receptors.

Marketed formulations contain acamprosate calcium - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Acamprosate. University of Alberta. 19 November 2017. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

Acamprosate is thought to stabilize the chemical balance in the brain that would otherwise be disrupted by alcoholism, possibly by blocking glutaminergic N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, while gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors are activated. ... The mechanism of action of acamprosate in the maintenance of alcohol abstinence is not completely understood. Chronic alcohol exposure is hypothesized to alter the normal balance between neuronal excitation and inhibition. in vitro and in vivo studies in animals have provided evidence to suggest acamprosate may interact with glutamate and GABA neurotransmitter systems centrally, and has led to the hypothesis that acamprosate restores this balance. It seems to inhibit NMDA receptors while activating GABA receptors.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 3 Kalk NJ, Lingford-Hughes AR (February 2014). "The clinical pharmacology of acamprosate". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 77 (2): 315–323. doi:10.1111/bcp.12070. PMC 4014018. PMID 23278595.

- 1 2 3 Mason BJ, Heyser CJ (March 2010). "Acamprosate: a prototypic neuromodulator in the treatment of alcohol dependence". CNS & Neurological Disorders Drug Targets. 9 (1): 23–32. doi:10.2174/187152710790966641. PMC 2853976. PMID 20201812.

- ↑ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE (2009). "Chapter 15: Reinforcement and Addictive Disorders". In Sydor A, Brown RY (eds.). Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 372. ISBN 9780071481274.

- ↑ Möykkynen T, Korpi ER (July 2012). "Acute effects of ethanol on glutamate receptors". Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 111 (1): 4–13. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7843.2012.00879.x. PMID 22429661.

- ↑ Tsai G, Coyle JT (1998). "The role of glutamatergic neurotransmission in the pathophysiology of alcoholism". Annual Review of Medicine. 49: 173–184. doi:10.1146/annurev.med.49.1.173. PMID 9509257.

- ↑ Tsai GE, Ragan P, Chang R, Chen S, Linnoila VM, Coyle JT (June 1998). "Increased glutamatergic neurotransmission and oxidative stress after alcohol withdrawal". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 155 (6): 726–732. PMID 9619143.

- 1 2 De Witte P, Littleton J, Parot P, Koob G (2005). "Neuroprotective and abstinence-promoting effects of acamprosate: elucidating the mechanism of action". CNS Drugs. 19 (6): 517–537. doi:10.2165/00023210-200519060-00004. PMID 15963001. S2CID 11563216.

- ↑ Mayer S, Harris BR, Gibson DA, Blanchard JA, Prendergast MA, Holley RC, Littleton J (October 2002). "Acamprosate, MK-801, and ifenprodil inhibit neurotoxicity and calcium entry induced by ethanol withdrawal in organotypic slice cultures from neonatal rat hippocampus". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 26 (10): 1468–1478. doi:10.1097/00000374-200210000-00003. PMID 12394279.

- ↑ al Qatari M, Khan S, Harris B, Littleton J (September 2001). "Acamprosate is neuroprotective against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity when enhanced by ethanol withdrawal in neocortical cultures of fetal rat brain". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 25 (9): 1276–1283. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02348.x. PMID 11584146.

- ↑ Trevor AJ (2017). "The Alcohols". In Katzung BG (ed.). Basic & Clinical Pharmacology (14th ed.). New York. ISBN 9781259641152. OCLC 1015240036.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 Berfield S (27 May 2002). "A CEO and His Son". Bloomberg Businessweek.

- ↑ "Press release: Forest Laboratories Announces Agreement For Alcohol Addiction Treatment". Forest Labs via Evaluate Group. October 23, 2001.

- ↑ "FDA Approves New Drug for Treatment of Alcoholism". FDA Talk Paper. Food and Drug Administration. 2004-07-29. Archived from the original on 2008-01-17. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- ↑ "Acamprosate generics". DrugPatentWatch. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ↑ "Acamprosate - Confluence Pharmaceuticals". AdisInsight. Springer Nature Switzerland AG. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- ↑ Mann K, Kiefer F, Spanagel R, Littleton J (July 2008). "Acamprosate: recent findings and future research directions". Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 32 (7): 1105–1110. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00690.x. PMID 18540918.