Cyclic dimer and trimer examples | |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC names

3,3-Dimethyl-1,2-dioxacyclopropane (monomer) 3,3,6,6-Tetramethyl-1,2,4,5-tetraoxane (dimer) 3,3,6,6,9,9-Hexamethyl- 3,3,6,6,9,9,12,12-Octamethyl- | |||

| Other names

Triacetone triperoxide Peroxyacetone Mother of Satan | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

| ||

| ChemSpider | |||

| E number | E929 (glazing agents, ...) | ||

PubChem CID |

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C6H12O4 (dimer) C9H18O6 (trimer) C12H24O8 (tetramer) | |||

| Molar mass | 148.157 g/mol (dimer) 222.24 g/mol (trimer) | ||

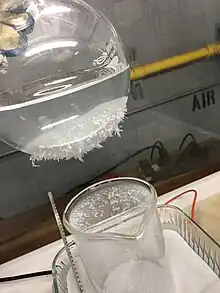

| Appearance | White crystalline solid | ||

| Melting point | 131.5 to 133 °C (dimer)[1] 91 °C (trimer) | ||

| Boiling point | 97 to 160 °C (207 to 320 °F; 370 to 433 K) | ||

| Insoluble | |||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling: | |||

| |||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Explosive data | |||

| Shock sensitivity | High/High when wet | ||

| Friction sensitivity | High/moderate when wet | ||

| Detonation velocity | 5300 m/s at maximum density (1.18 g/cm3), about 2500–3000 m/s near 0.5 g/cm3 17,384 ft/s 3.29 miles per second | ||

| RE factor | 0.80 | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |||

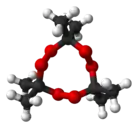

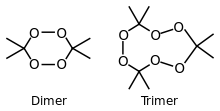

Acetone peroxide (/æsəˈtəʊn pɛrˈɒksaɪd/ ⓘ also called APEX and mother of Satan[2][3]) is an organic peroxide and a primary explosive. It is produced by the reaction of acetone and hydrogen peroxide to yield a mixture of linear monomer and cyclic dimer, trimer, and tetramer forms. The dimer is known as diacetone diperoxide (DADP). The trimer is known as triacetone triperoxide (TATP) or tri-cyclic acetone peroxide (TCAP). Acetone peroxide takes the form of a white crystalline powder with a distinctive bleach-like odor (when impure) or a fruit-like smell when pure, and can explode powerfully if subjected to heat, friction, static electricity, concentrated sulfuric acid, strong UV radiation or shock. Until about 2015, explosives detectors were not set to detect non-nitrogenous explosives, as most explosives used preceding 2015 were nitrogen-based. TATP, being nitrogen-free, has been used as the explosive of choice in several terrorist bomb attacks since 2001.

History

Acetone peroxide (specifically, triacetone triperoxide) was discovered in 1895 by the German chemist Richard Wolffenstein.[4][5][6] Wolffenstein combined acetone and hydrogen peroxide, and then he allowed the mixture to stand for a week at room temperature, during which time a small quantity of crystals precipitated, which had a melting point of 97 °C (207 °F).[7]

In 1899, Adolf von Baeyer and Victor Villiger described the first synthesis of the dimer and described use of acids for the synthesis of both peroxides.[8][9][10][11][12] Baeyer and Villiger prepared the dimer by combining potassium persulfate in diethyl ether with acetone, under cooling. After separating the ether layer, the product was purified and found to melt at 132–133 °C (270–271 °F).[13] They found that the trimer could be prepared by adding hydrochloric acid to a chilled mixture of acetone and hydrogen peroxide.[14] By using the depression of freezing points to determine the molecular weights of the compounds, they also determined that the form of acetone peroxide that they had prepared via potassium persulfate was a dimer, whereas the acetone peroxide that had been prepared via hydrochloric acid was a trimer, like Wolffenstein's compound.[15]

Work on this methodology and on the various products obtained, was further investigated in the mid-20th century by Milas and Golubović.[16]

Chemistry

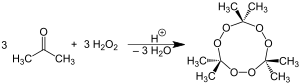

The chemical name acetone peroxide is most commonly used to refer to the cyclic trimer, the product of a reaction between two precursors, hydrogen peroxide and acetone, in an acid-catalyzed nucleophilic addition, although various further monomeric and dimeric forms are possible.

Specifically, two dimers, one cyclic (C6H12O4) and one open chain (C6H14O4), as well as an open dihydroperoxide monomer (C3H8O4),[17] can also be formed; under a particular set of conditions of reagent and acid catalyst concentration, the cyclic trimer is the primary product.[16] A tetrameric form has also been described, under different catalytic conditions, however.[18] the synthesis of tetrameric acetone peroxide has been disputed.[19][20] Under neutral conditions, the reaction is reported to produce the monomeric organic peroxide.[16]

The most common route for nearly pure TATP is H2O2/acetone/HCl in 1:1:0.25 molar ratios, using 30% hydrogen peroxide. This product contains very little or none of DADP with some very small traces of chlorinated compounds. Product that contains large fraction of DADP can be obtained from 50% H2O2 using large amounts of concentrated sulfuric acid as catalyst or alternatively with 30% H2O2 and massive amounts of HCl as a catalyst.[20]

The product made by using hydrochloric acid is regarded as more stable than the one made using sulfuric acid. It is known that traces of sulfuric acid trapped inside the formed acetone peroxide crystals lead to instability. In fact, the trapped sulfuric acid can induce detonation at temperatures as low as 50 °C (122 °F). This is the most likely mechanism behind accidental explosions of acetone peroxide that occur during drying on heated surfaces.[21]

Triacetone triperoxide forms in 2-propanol upon standing for long periods of time in the presence of air.[22]

Organic peroxides in general are sensitive, dangerous explosives, and all forms of acetone peroxide are sensitive to initiation. TATP decomposes explosively; examination of the explosive decomposition of TATP at the very edge of detonation front predicts "formation of acetone and ozone as the main decomposition products and not the intuitively expected oxidation products."[23] Very little heat is created by the explosive decomposition of TATP at the very edge of the detonation front; the foregoing computational analysis suggests that TATP decomposition is an entropic explosion.[23] However, this hypothesis has been challenged as not conforming to actual measurements.[24] The claim of entropic explosion has been tied to the events just behind the detonation front. The authors of the 2004 Dubnikova et al. study confirm that a final redox reaction (combustion) of ozone, oxygen and reactive species into water, various oxides and hydrocarbons takes place within about 180 ps after the initial reaction - within about a micron of the detonation wave. Detonating crystals of TATP ultimately reach temperature of 2,300 K (2,030 °C; 3,680 °F) and pressure of 80 kbar.[25] The final energy of detonation is about 2800 kJ/kg (measured in helium) - enough to briefly raise the temperature of gaseous products to 2,000 °C (3,630 °F). Volume of gases at STP is 855 L/kg for TATP and 713 L/kg for DADP (measured in helium).[24]

The tetrameric form of acetone peroxide, prepared under neutral conditions using a tin catalyst in the presence of a chelator or general inhibitor of radical chemistry, is reported to be more chemically stable, although still a very dangerous primary explosive.[18] Its synthesis has been disputed.[20]

Both TATP and DADP are prone to loss of mass via sublimation. DADP has lower molecular weight and higher vapor pressure. This means that DADP is more prone to sublimation than TATP. This can lead to dangerous crystal growth when the vapors deposit if the crystals have been stored in a container with a threaded lid. This process of repeated sublimation and deposition also results in a change in crystal size via Ostwald ripening.

Several methods can be used for trace analysis of TATP,[26] including gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS),[27][28][29][30][31] high performance liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (HPLC/MS),[32][33][34][35][36] and HPLC with post-column derivitization.[37]

Acetone peroxide is soluble in toluene, chloroform, acetone, dichloromethane and methanol.[38] Recrystalization of primary explosives may yield large crystals that detonate spontaneously due to internal strain.[39]

Industrial uses

Ketone peroxides, including acetone peroxide and methyl ethyl ketone peroxide, find application as initiators for polymerization reactions, e.g., silicone or polyester resins, in the making of fiberglass-reinforced composites. For these uses, the peroxides are typically in the form of a dilute solution in an organic solvent; methyl ethyl ketone peroxide is more common for this purpose, as it is stable in storage.

Acetone peroxide is used as a flour bleaching agent to bleach and "mature" flour.[40]

Acetone peroxides are unwanted by-products of some oxidation reactions such as those used in phenol syntheses.[41] Due to their explosive nature, their presence in chemical processes and chemical samples creates potential hazardous situations. Accidental occurrence at illicit MDMA laboratories is possible.[42] Numerous methods are used to reduce their appearance, including shifting pH to more alkaline, adjusting reaction temperature, or adding inhibitors of their production.[41] For example, triacetone peroxide is the major contaminant found in diisopropyl ether as a result of photochemical oxidation in air.[43]

Use in improvised explosive devices

TATP has been used in bomb and suicide attacks and in improvised explosive devices, including the London bombings on 7 July 2005, where four suicide bombers killed 52 people and injured more than 700.[44][45][46][47] It was one of the explosives used by the "shoe bomber" Richard Reid[48][49][47] in his 2001 failed shoe bomb attempt and was used by the suicide bombers in the November 2015 Paris attacks,[50] 2016 Brussels bombings,[51] Manchester Arena bombing, June 2017 Brussels attack,[52] Parsons Green bombing,[53] the Surabaya bombings,[54] and the 2019 Sri Lanka Easter bombings.[55][56] Hong Kong police claim to have found 2 kg (4.4 lb) of TATP among weapons and protest materials in July 2019, when mass protests were taking place against a proposed law allowing extradition to mainland China.[57]

TATP shockwave overpressure is 70% of that for TNT, the positive phase impulse is 55% of the TNT equivalent. TATP at 0.4 g/cm3 has about one-third of the brisance of TNT (1.2 g/cm3) measured by the Hess test.[58]

TATP is attractive to terrorists because it is easily prepared from readily available retail ingredients, such as hair bleach and nail polish remover.[50] It was also able to evade detection because it is one of the few high explosives that do not contain nitrogen,[59] and could therefore pass undetected through standard explosive detection scanners, which were hitherto designed to detect nitrogenous explosives.[60] By 2016, explosives detectors had been modified to be able to detect TATP, and new types were developed.[61][62]

Legislative measures to limit the sale of hydrogen peroxide concentrated to 12% or higher have been made in the European Union.[63]

A key disadvantage is the high susceptibility of TATP to accidental detonation, causing injuries and deaths among illegal bomb-makers, which has led to TATP being referred to as the "Mother of Satan".[62][59] TATP was found in the accidental explosion that preceded the 2017 terrorist attacks in Barcelona and surrounding areas.[64]

Large-scale TATP synthesis is often betrayed by excessive bleach-like or fruity smells. This smell can even penetrate into clothes and hair in amounts that are quite noticeable, this was reported in the 2016 Brussels bombings.[65]

References

- ↑ Federoff, Basil T. et al., Encyclopedia of Explosives and Related Items (Springfield, Virginia: National Technical Information Service, 1960), vol. 1, p. A41.

- ↑ Berezow, Alex (14 November 2018). "TATP: The Chemistry of 'Mother of Satan' Explosive". American Council on Science and Health.

- ↑ Swartz, Anna (24 March 2016). "What Is 'Mother of Satan'? What You Should Know About Explosive Used in Brussels Attacks". Yahoo News.

- ↑ Wolffenstein R (1895). "Über die Einwirkung von Wasserstoffsuperoxyd auf Aceton und Mesityloxyd" [On the effect of hydrogen peroxide on acetone and mesityl oxide]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 28 (2): 2265–2269. doi:10.1002/cber.189502802208. Wolffenstein determined that acetone peroxide formed a trimer, and he proposed a structural formula for it. From pp. 2266–2267: "Die physikalischen Eigenschaften des Superoxyds, der feste Aggregatzustand, die Unlöslichkeit in Wasser etc. sprachen dafür, dass das Molekulargewicht desselben ein grösseres wäre, als dem einfachen Atomverhältnisse entsprach. … Es lag also ein trimolekulares Acetonsuperoxyd vor, das aus dem monomolekularen entstehen kann, indem sich die Bindungen zwischen je zwei Sauerstoffatomen lösen und zur Verknüpfung mit den Sauerstoffatomen eines benachbarten Moleküls dienen. Man gelangt so zur folgenden Constitutionsformel: [diagram of proposed molecular structure of the trimer of acetone peroxide] . Diese eigenthümliche ringförmig constituirte Verbindung soll Tri-Cycloacetonsuperoxyd genannt werden." (The physical properties of the peroxide, its solid state of aggregation, its insolubility in water, etc., suggested that its molecular weight would be a greater [one] than corresponded to its simple empirical formula. … Thus [the result of the molecular weight determination showed that] there was present a tri-molecular acetone peroxide, which can arise from the monomer by the bonds between each pair of oxygen atoms [on one molecule of acetone peroxide] breaking and serving as links to the oxygen atoms of a neighboring molecule. One thus arrives at the following structural formula: [diagram of proposed molecular structure of the trimer of acetone peroxide] . This strange ring-shaped compound shall be named "tri-cycloacetone peroxide".)

- ↑ Wolfenstein R (1895) Deutsches Reichspatent 84,953

- ↑ Matyáš R, Pachman J (2013). Primary Explosives. Berlin: Springer. p. 262. ISBN 978-3-642-28436-6.

- ↑ Wolffenstein 1895, p. 2266.

- ↑ Baeyer, Adolf; Villiger, Victor (1899). "Einwirkung des Caro'schen Reagens auf Ketone" [Effect of Caro's reagent on ketones [part 1]]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 32 (3): 3625–3633. doi:10.1002/cber.189903203151. see p. 3632.

- ↑ Baeyer A, Villiger V (1900a). "Über die Einwirkung des Caro'schen Reagens auf Ketone" [On the effect of Caro's reagent on ketones [part 3]]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 33 (1): 858–864. doi:10.1002/cber.190003301153.

- ↑ Baeyer A, Villiger V (1900b). "Über die Nomenclatur der Superoxyde und die Superoxyde der Aldehyde" [On the nomenclature of peroxides and the peroxide of aldehydes] (PDF). Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft. 33 (2): 2479–2487. doi:10.1002/cber.190003302185.

- ↑ Federoff, Basil T. et al., Encyclopedia of Explosives and Related Items (Springfield, Virginia: National Technical Information Service, 1960), vol. 1, p. A41.

- ↑ Matyáš, Robert and Pachman, Jirí, ed.s, Primary Explosives (Berlin, Germany: Springer, 2013), p. 257.

- ↑ Baeyer & Villiger 1899, p. 3632.

- ↑ Baeyer & Villiger 1900a, p. 859.

- ↑ Baeyer & Villiger 1900a, p. 859 "Das mit dem Caro'schen Reagens dargestellte, bei 132–133° schmelzende Superoxyd gab bei der Molekulargewichtsbestimmung nach der Gefrierpunktsmethode Resultate, welche zeigen, dass es dimolekular ist. Um zu sehen, ob das mit Salzsäure dargestellte Superoxyd vom Schmp. 90–94° mit dem Wolffenstein'schen identisch ist, wurde davon ebenfalls eine Molekulargewichtsbestimmung gemacht, welche auf Zahlen führte, die für ein trimolekulares Superoxyd stimmen." [The peroxide that was prepared with Caro's reagent and that melted at 132–133 °C (270–271 °F) gave – according to a determination of molecular weight via the freezing point method – results which show that it is dimolecular. In order to see whether the peroxide that was prepared with hydrochloric acid and that has a melting point of 90–94 °C (194–201 °F) is identical to Wolffenstein's, its molecular weight was likewise determined, which led to values that are correct for a trimolecular peroxide.]

- 1 2 3 Milas NA, Golubović A (1959). "Studies in Organic Peroxides. XXVI. Organic Peroxides Derived from Acetone and Hydrogen Peroxide". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 81 (24): 6461–6462. doi:10.1021/ja01533a033.

- ↑ This is not the DMDO monomer referred to in the Chembox, but rather the open chain, dihydro monomer described by Milas & Goluboviç, op. cit.

- 1 2 Jiang H, Chu G, Gong H, Qiao Q (1999). "Tin Chloride Catalysed Oxidation of Acetone with Hydrogen Peroxide to Tetrameric Acetone Peroxide". Journal of Chemical Research. 28 (4): 288–289. doi:10.1039/a809955c. S2CID 95733839.

- ↑ Primary Explosives - Robert Matyáš, Jiří Pachman (auth.), p.275

- 1 2 3 Matyáš, R.; Pachman, J. (8 February 2010). "Study of TATP: Influence of reaction conditions on product composition". Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics. 35 (1): 31–37. doi:10.1002/prep.200800044. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ↑ Matyas R, Pachman J (1 July 2007). "Thermal stability of triacetone triperoxide". Science and Technology of Energetic Materials. 68: 111–116.

- ↑ Pye, Cory (10 June 2020). "Chemical Safety: TATP Formation in 2-Propanol". ACS Chemical Health & Safety. 27 (5): 279. doi:10.1021/acs.chas.0c00061. S2CID 225762474.

- 1 2 Dubnikova, Faina; Kosloff, Ronnie; Almog, Joseph; Zeiri, Yehuda; Boese, Roland; Itzhaky, Harel; Alt, Aaron; Keinan, Ehud (2005). "Decomposition of Triacetone Triperoxide is an Entropic Explosion". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (4): 1146–1159. doi:10.1021/ja0464903. PMID 15669854.

- 1 2 Sinditskii VP, Koltsov VI, Egorshev, VY, Patrikeev DI, Dorofeeva OV (2014). "Thermochemistry of cyclic acetone peroxides". Thermochimica Acta. 585: 10–15. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2014.03.046.

- ↑ Van Duin AC, Zeiri Y, Dubnikova F, Kosloff R, Goddard WA (2005). "Atomistic-Scale Simulations of the Initial Chemical Events in the Thermal Initiation of Triacetonetriperoxide". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 127 (31): 11053–62. doi:10.1021/ja052067y. PMID 16076213.

- ↑ Schulte-Ladbeck R, Vogel M, Karst U (October 2006). "Recent methods for the determination of peroxide-based explosives". Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 386 (3): 559–65. doi:10.1007/s00216-006-0579-y. PMID 16862379. S2CID 38737572.

- ↑ Muller D, Levy A, Shelef R, Abramovich-Bar S, Sonenfeld D, Tamiri T (September 2004). "Improved method for the detection of TATP after explosion". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 49 (5): 935–8. doi:10.1520/JFS2003003. PMID 15461093.

- ↑ Stambouli A, El Bouri A, Bouayoun T, Bellimam MA (December 2004). "Headspace-GC/MS detection of TATP traces in post-explosion debris". Forensic Science International. 146 Suppl: S191–4. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.09.060. PMID 15639574.

- ↑ Oxley JC, Smith JL, Shinde K, Moran J (2005). "Determination of the Vapor Density of Triacetone Triperoxide (TATP) Using a Gas Chromatography Headspace Technique". Propellants, Explosives, Pyrotechnics. 30 (2): 127. doi:10.1002/prep.200400094.

- ↑ Sigman ME, Clark CD, Fidler R, Geiger CL, Clausen CA (2006). "Analysis of triacetone triperoxide by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry and gas chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry by electron and chemical ionization". Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 20 (19): 2851–7. Bibcode:2006RCMS...20.2851S. doi:10.1002/rcm.2678. PMID 16941533.

- ↑ Romolo FS, Cassioli L, Grossi S, Cinelli G, Russo MV (January 2013). "Surface-sampling and analysis of TATP by swabbing and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry". Forensic Science International. 224 (1–3): 96–100. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.11.005. PMID 23219697.

- ↑ Widmer L, Watson S, Schlatter K, Crowson A (December 2002). "Development of an LC/MS method for the trace analysis of triacetone triperoxide (TATP)". The Analyst. 127 (12): 1627–32. Bibcode:2002Ana...127.1627W. doi:10.1039/B208350G. PMID 12537371.

- ↑ Xu X, van de Craats AM, Kok EM, de Bruyn PC (November 2004). "Trace analysis of peroxide explosives by high performance liquid chromatography-atmospheric pressure chemical ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-APCI-MS/MS) for forensic applications". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 49 (6): 1230–6. PMID 15568694.

- ↑ Cotte-Rodríguez I, Hernandez-Soto H, Chen H, Cooks RG (March 2008). "In situ trace detection of peroxide explosives by desorption electrospray ionization and desorption atmospheric pressure chemical ionization". Analytical Chemistry. 80 (5): 1512–9. doi:10.1021/ac7020085. PMID 18247583.

- ↑ Sigman ME, Clark CD, Caiano T, Mullen R (2008). "Analysis of triacetone triperoxide (TATP) and TATP synthetic intermediates by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry". Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 22 (2): 84–90. Bibcode:2008RCMS...22...84S. doi:10.1002/rcm.3335. PMID 18058960.

- ↑ Sigman ME, Clark CD, Painter K, Milton C, Simatos E, Frisch JL, McCormick M, Bitter JL (February 2009). "Analysis of oligomeric peroxides in synthetic triacetone triperoxide samples by tandem mass spectrometry". Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 23 (3): 349–56. Bibcode:2009RCMS...23..349S. doi:10.1002/rcm.3879. PMID 19125413.

- ↑ Schulte-Ladbeck R, Kolla P, Karst U (February 2003). "Trace analysis of peroxide-based explosives". Analytical Chemistry. 75 (4): 731–5. doi:10.1021/ac020392n. PMID 12622359.

- ↑ Kende, Anikó; Lebics, Ferenc; Eke, Zsuzsanna; Torkos, Kornél (2008). "Trace level triacetone-triperoxide identification with SPME–GC-MS in model systems". Microchimica Acta. 163 (3–4): 335–338. doi:10.1007/s00604-008-0001-x. S2CID 97978057.

- ↑ Primary Explosives - page 278, ISBN 9783642284359

- ↑ Ferrari CG, Higashiuchi K, Podliska JA (1963). "Flour Maturing and Bleaching with Acyclic Acetone Peroxides" (PDF). Cereal Chemistry. 40: 89–100. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- 1 2 US 5003109, Costantini, Michel, "Destruction of acetone peroxide", published 1991-03-26

- ↑ Burke, Robert A. (25 July 2006). Counter-Terrorism for Emergency Responders, Second Edition. CRC Press LLC. p. 213. ISBN 9781138747623.

- ↑ Acree F, Haller HL (1943). "Trimolecular Acetone Peroxide in Isopropyl Ether". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 65 (8): 1652. doi:10.1021/ja01248a501.

- ↑ "The real story of 7/7", The Observer, 7 May 2006

- ↑ London bombers used everyday materials—U.S. police, Reuters, 4 August 2005

- ↑ Naughton P (15 July 2005). "TATP is suicide bombers' weapon of choice". The Times (UK). Archived from the original on 10 February 2008.

- 1 2 Vince G (15 July 2005). "Explosives linked to London bombings identified". New Scientist.

- ↑ "Judge denies bail to accused shoe bomber". CNN. 28 December 2001.

- ↑ "Terrorist Use of TATP Explosive". officialconfusion.com. 25 July 2005.

- 1 2 Callimachi R, Rubin AJ, Fourquet L (19 March 2016). "A View of ISIS's Evolution in New Details of Paris Attacks". The New York Times.

- ↑ "'La mère de Satan' ou TATP, l'explosif préféré de l'EI" ['Mother of Satan' or TATP, the preferred explosive for IEDs]. LeVif.be Express (in French). 23 March 2016.

- ↑ Doherty B (25 May 2017). "Manchester bomb used same explosive as Paris and Brussels attacks, says US lawmaker". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ Dearden, Lizzie (16 September 2017). "London attack: Parsons Green bombers 'still out there' more than 24 hours after Tube blast, officials warn". The Independent. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ↑ "'Mother of Satan' explosives used in Surabaya church bombings: Police". The Jakarta Post. 14 May 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ↑ "Asia Times | 'Mother of Satan' explosive used in Sri Lanka bombings | Article". Asia Times. 24 April 2019. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- ↑ TATP explosive used in Easter attacks – Former DIG Nimal Lewke News First (Sri Lanka), Retrieved on 23 April 2019.

- ↑ "Hong Kong protests: Police probe link of huge explosives haul". BBC News. 20 July 2019.

- ↑ Pachman, J; Matyáš, R; Künzel, M (2014). "Study of TATP: Blast characteristics and TNT equivalency of small charges". Shock Waves. 24 (4): 439. Bibcode:2014ShWav..24..439P. doi:10.1007/s00193-014-0497-4. S2CID 122101166.

- 1 2 Glas K (6 November 2006). "TATP: Countering the Mother of Satan". The Future of Things. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

The tremendous devastative force of TATP, together with the relative ease of making it, as well as the difficulty in detecting it, made TATP one of the weapons of choice for terrorists

- ↑ "Feds are all wet on airport security". Star-Ledger. Newark, New Jersey. 24 August 2006. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

At the moment, Watts said, the screening devices are set to detect nitrogen-based explosives, a category that doesn't include TATP

- ↑ Jacoby, Mitch (29 March 2016). "Explosive used in Brussels isn't hard to detect". Chemical & Engineering News. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- 1 2 Genuth I, Fresco-Cohen L (6 November 2006). "TATP: Countering the Mother of Satan". The Future of Things. Retrieved 24 September 2009.

The tremendous devastative force of TATP, together with the relative ease of making it, as well as the difficulty in detecting it, made TATP one of the weapons of choice for terrorists

- ↑ "Regulation (EU) No 2019/1148 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on the marketing and use of explosives precursors".

- ↑ Watts J, Burgen S (21 August 2017). "Police extend hunt for Barcelona attack suspect across Europe". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ Andrew Higgins; Kimiko de Freytas-Tamura (26 March 2016). "In Brussels Bombing Plot, a Trail of Dots Not Connected". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 March 2016.