| Red spruce | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Gymnospermae |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Pinaceae |

| Genus: | Picea |

| Species: | P. rubens |

| Binomial name | |

| Picea rubens | |

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

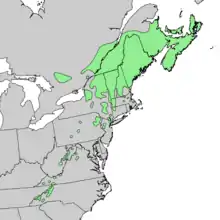

Picea rubens, commonly known as red spruce, is a species of spruce native to eastern North America, ranging from eastern Quebec and Nova Scotia, west to the Adirondack Mountains and south through New England along the Appalachians to western North Carolina.[3][4][5] This species is also known as yellow spruce, West Virginia spruce, eastern spruce, and he-balsam.[6][7] Red spruce is the provincial tree of Nova Scotia.[4]

Description

Red spruce is a perennial,[8] shade-tolerant, late successional[9] coniferous tree that under optimal conditions grows to 18–40 m (59–131 ft) tall with a trunk diameter of about 60 cm (24 in), though exceptional specimens can reach 46 m (151 ft) tall and 100 cm (39 inches) in diameter. It has a narrow conical crown. The leaves are needle-like, yellow-green, 12–15 mm (15⁄32–19⁄32 in) long, four-sided, curved, with a sharp point, and extend from all sides of the twig. The bark is gray-brown on the surface and red-brown on the inside, thin, and scaly. The wood is light, soft, has narrow rings, and has a slight red tinge.[10] The cones are cylindrical, 3–5 cm (1+1⁄4–2 in) long, with a glossy red-brown color and stiff scales. The cones hang down from branches.[3][4][5][11]

Habitat

Red spruce grows at a slow to moderate rate, lives for 250 to 450+ years, and is very shade-tolerant when young.[12] It is often found in pure stands or forests mixed with eastern white pine, balsam fir, or black spruce. Along with Fraser fir, red spruce is one of two primary tree types in the southern Appalachian spruce-fir forest, a distinct ecosystem found only in the highest elevations of the Southern Appalachian Mountains.[13] Its habitat is moist but well-drained sandy loam, often at high altitudes. Red spruce can be easily damaged by windthrow and acid rain.

Notable red spruce forests can be seen at Gaudineer Scenic Area, a virgin red spruce forest located in West Virginia, the Canaan Valley, Roaring Plains West Wilderness, Dolly Sods Wilderness, Spruce Mountain and Spruce Knob all also in West Virginia and all sites of former extensive red spruce forest. Some areas of this forest, particularly in Roaring Plains West Wilderness, Dolly Sods Wilderness as well as areas of Spruce Mountain are making a rather substantial recovery.

Related species

It is closely related to black spruce, and hybrids between the two are frequent where their ranges meet.[3][4][5] Genetic data suggests that the red spruce peripatrically speciated from the black spruce during the Pleistocene due to glaciation.[14][15]

Uses

Red spruce is used for Christmas trees and is an important wood used in making paper pulp. It is also an excellent tonewood, and is used in many higher-end acoustic guitars and violins, as well as musical soundboard. The sap can be used to make spruce gum.[11] Leafy red spruce twigs are boiled with sugar and flavoring to make spruce beer.[16] Also it can be made into spruce pudding. It can also be used as construction lumber and is good for millwork and for crates.[17]

Damaging factors

Like most trees, red spruce is subject to insect parasitism. Their insect enemy is the spruce budworm, although it is a bigger problem for white spruce and balsam fir.[18] Other issues that have been damaging red spruce has been the increase in acid rain and current climate change.[19]

One of the consequences of acid rain deposition is the decrease of soil exchangeable calcium and increase of aluminum. This is because acid precipitation disrupts cation and nutrition cycling in forest ecosystems. Components of acid rain such as H+, NO3−, and SO42- limit the uptake of calcium by trees and can increase aluminum availability.[20]

Calcium concentration is important for red spruce for physiological processes such as dark respiration and cold tolerance, as well as disease resistance, signal transduction, membrane and cell wall synthesis and function, and regulation of stomata. Conversely, dissolved aluminum can be toxic or can interfere with root uptake of calcium and other nutrients. At the ecosystem and community levels, Calcium availability is associated with community composition, mature tree growth, and ecosystem productivity. One study testing the effects of added aluminum to soil, found that P. rubens mortality rate increased under these conditions.[21]

During the 1980s, increased acid deposition contributed to a loss of high-elevation red spruce trees, due to leached calcium and decreased freezing tolerance.[22] Additionally, the structure of the spruce needle enhances the capture of water and particles, which has been shown to add to soil acidification, nutrient leaching, and forest decline.[23]

However, more recently, reductions in acid deposition have contributed to red spruce resurgence in some mountain areas in the northeastern United States. This increase in red spruce growth has been associated with an increase in rainfall pH, which reduces bulk acidic deposition. This suggests that policies aiming to reduce atmospheric pollution in this area have been effective, although other species sensitive to soil acidification, such as sugar maple, are still continuing to decline.[22]

Conservation

The red spruce has low genetic diversity as well as a narrow ecological niche, meaning the tree is easily susceptible to changes within its environment.[24] The Central Appalachian Spruce Restoration Initiative (CASRI)[25] seeks to unite diverse partners with the goal of restoring historic red spruce ecosystems across the high-elevation landscapes of central Appalachians. The partners that make up this diverse group are Appalachian Mountain Joint Venture, Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative, Canaan Valley National Wildlife Refuge, Natural Resources Conservation Service, The Mountain Institute, The Nature Conservancy, Trout Unlimited, U.S. Forest Service Northern Research Station, U.S. Forest Service Monongahela National Forest, West Virginia Division of Natural Resources, West Virginia Division of Forestry, West Virginia Highlands Conservancy, West Virginia State Parks, and West Virginia University.[26]

Prior to the late 1800s, 600,000 hectares (1,500,000 acres) of red spruce were in West Virginia. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, a vast amount of logging began in the state and the number of red spruce dwindled to 12,000 hectares (30,000 acres). Silviculture is being used to help restore the population of the lost red spruce.[27]

Significant efforts have been made to increase the growth of red spruce trees in western North Carolina. Most notably by Molly Tartt on behalf of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Tartt, a resident of Brevard North Carolina, embarked on a mission to find the lost red spruce Pisgah Forest that had been planted by the DAR as a memorial to the lives lost during the American Revolution. The forest, consisting of 50,000 trees was dedicated in 1940 and had until recently been forgotten until Tartt located and identified the forest.[28]

References

- ↑ Farjon, A. (2013). "Picea rubens". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013: e.T42335A2973542. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T42335A2973542.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ "Picea rubens Sarg.". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew – via The Plant List. Note that this website has been superseded by World Flora Online

- 1 2 3 Farjon, A. (1990). Pinaceae. Drawings and Descriptions of the Genera. Koeltz Scientific Books ISBN 3-87429-298-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Taylor, Ronald J. (1993). "Picea rubens". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 2. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- 1 2 3 Earle, Christopher J., ed. (2018). "Picea rubens". The Gymnosperm Database.

- ↑ Blum, Barton M. (1990). "Picea rubens". In Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H. (eds.). Conifers. Silvics of North America. Washington, D.C.: United States Forest Service (USFS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Vol. 1 – via Southern Research Station.

- ↑ Peattie, Donald Culross (1948-01-01). A Natural History of Trees of Eastern and Central North America. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 51. ISBN 0-395-58174-5.

- ↑ "Red Spruce (Rubens)". Garden Guides. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ↑ Dumais, D; Prevost, M (June 2007). "Management for red spruce conservation in Quebec: The importance of some physiological and ecological characteristics – A review". Forestry Chronicle. 83 (3): 378–392. doi:10.5558/tfc83378-3. ProQuest 294760995.

- ↑ "Red Spruce" (PDF). USDA NRCS. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- 1 2 "Red Spruce". A handbook of Maritime trees. Atlantic Forestry Centre. Archived from the original on 2008-08-18.

- ↑ "Eastern OLDLIST: A database of maximum tree ages for Eastern North America".

- ↑ White, Peter (2006). "Boreal Forest". Encyclopedia of Appalachia. University of Tennessee Press. pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Juan P. Jaramillo-Correa & Jean Bousquet (2003), "New evidence from mitochondrial DNA of a progenitor-derivative species relationship between black and red spruce (Pinaceae)", American Journal of Botany, 90 (12): 1801–1806, doi:10.3732/ajb.90.12.1801, PMID 21653356

- ↑ Isabelle Gamache, Juan P. Jaramillo-Correa, Sergey Payette, & Jean Bousquet (2003), "Diverging patterns of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA diversity in subarctic black spruce: imprint of a founder effect associated with postglacial colonization", Molecular Ecology, 12 (4): 891–901, doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01800.x, PMID 12753210, S2CID 20234158

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Little, Elbert L. (1980). The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Trees: Eastern Region. New York: Knopf. p. 285. ISBN 0-394-50760-6.

- ↑ "Red Spruce". The Wood Database. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ↑ "Red Spruce" at the Encyclopedia of Life

- ↑ Houle, Daniel (2012). "Compositional vegetation changes and increased red spruce abundance during the Little Ice Age in a sugar maple forest of north-eastern North America". Plant Ecology. 213 (6): 1027–1035. doi:10.1007/s11258-012-0062-0. S2CID 15104515.

- ↑ Schaberg, P. G.; DeHayes, D. H.; Hawley, G. J.; Strimbeck, G. R.; Cumming, J. R.; Murakami, P. F.; Borer, C. H. (2000-01-01). "Acid mist and soil Ca and Al alter the mineral nutrition and physiology of red spruce". Tree Physiology. 20 (2): 73–85. doi:10.1093/treephys/20.2.73. ISSN 0829-318X. PMID 12651475.

- ↑ Kobe, Richard K; Likens, Gene E; Eagar, Christopher (2002-06-01). "Tree seedling growth and mortality responses to manipulations of calcium and aluminum in a northern hardwood forest". Canadian Journal of Forest Research. 32 (6): 954–966. doi:10.1139/x02-018. ISSN 0045-5067.

- 1 2 Wason, Jay W.; Beier, Colin M.; Battles, John J.; Dovciak, Martin (2019). "Acidic Deposition and Climate Warming as Drivers of Tree Growth in High-Elevation Spruce-Fir Forests of the Northeastern US". Frontiers in Forests and Global Change. 2. doi:10.3389/ffgc.2019.00063. ISSN 2624-893X.

- ↑ Pierret, Marie-Claire; Viville, Daniel; Dambrine, Etienne; Cotel, Solenn; Probst, Anne (2019-04-01). "Twenty-five year record of chemicals in open field precipitation and throughfall from a medium-altitude forest catchment (Strengbach - NE France): An obvious response to atmospheric pollution trends". Atmospheric Environment. 202: 296–314. Bibcode:2019AtmEn.202..296P. doi:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.12.026. ISSN 1352-2310.

- ↑ Parmar, Rajni; Cattonaro, Federica; Phillips, Carrie; Vassiliev, Serguei; Morgante, Michele; Rajora, Om P. (2022-12-03). "Assembly and Annotation of Red Spruce (Picea rubens) Chloroplast Genome, Identification of Simple Sequence Repeats, and Phylogenetic Analysis in Picea". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (23): 15243. doi:10.3390/ijms232315243. hdl:11390/1240084. ISSN 1422-0067.

- ↑ Burks, Evan (Dec 2010). "Return of the Red Spruce". Wonderful West Virginia. 74 (12): 6–11.

- ↑ Bove, Jennifer. "Appalachian Red Spruce Forest". Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ↑ Rentch, James; T. Schuler; M. Ford; G. Nowacki (September 2007). "Red Spruce Stand Dynamics, Simulations, and Restoration Opportunities in the Central Appalachians". Restoration Ecology. 15 (3): 440–452. doi:10.1111/j.1526-100x.2007.00240.x. S2CID 85913515. ProQuest 289371889.

- ↑ "Daughters of the American Revolution brings forgotten forest to light".