| Afrikaans | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | [afriˈkɑːns] |

| Native to | |

| Ethnicity | |

Native speakers | 7.2 million (2016)[1] 10.3 million L2 speakers in South Africa (2002)[2] |

Early forms | |

| Signed Afrikaans[3] | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Die Taalkommissie |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | af |

| ISO 639-2 | afr |

| ISO 639-3 | afr |

| Glottolog | afri1274 |

| Linguasphere | 52-ACB-ba |

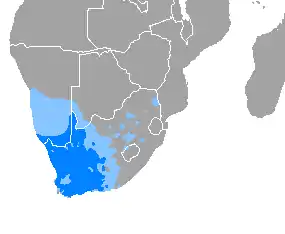

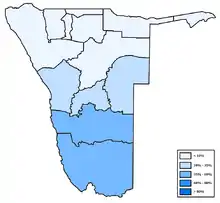

Dark Blue: Spoken by a majority; Light Blue: Spoken by a minority | |

Afrikaans (/ˌæfrɪˈkɑːns/ AF-rih-KAHNSS, /ˌɑːf-, -ˈkɑːnz/ AHF-, -KAHNZ)[4][5] is a West Germanic language that evolved in the Dutch Cape Colony from the Dutch vernacular[6][7] of Holland proper (i.e. the Hollandic dialect)[8][9] used by Dutch, French, and German settlers and people enslaved by them. Afrikaans gradually began to develop distinguishing characteristics during the course of the 18th century.[10] Now spoken in South Africa, Namibia and (to a lesser extent) Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe, estimates c. 2010 of the total number of Afrikaans speakers range between 15 and 23 million.[note 1] Most linguists consider Afrikaans to be a partly creole language.[11][12][13]

An estimated 90% to 95% of the vocabulary is of Dutch origin, with adopted words from other languages, including German and the Khoisan languages of Southern Africa.[note 2] Differences with Dutch include a more analytic-type morphology and grammar, and some pronunciations.[14] There is a large degree of mutual intelligibility between the two languages, especially in written form.[15]

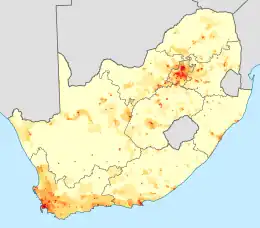

About 13.5% of the South African population (7 million people) speak Afrikaans as a first language, making it the third most common natively-spoken language in the country,[16] after Zulu and Xhosa. It has the widest geographic and racial distribution of the 12 official languages and is widely spoken and understood as a second or third language, although Zulu and English are estimated to be understood as a second language by a much larger proportion of the population.[note 3] It is the majority language of the western half of South Africa—the provinces of the Northern Cape and Western Cape—and the first language of 75.8% of Coloured South Africans (4.8 million people), 60.8% of Whites (2.7 million people), 1.5% of Blacks (600,000 people), and 4.6% of Indians (58,000 people).[17]

Etymology

The name of the language comes directly from the Dutch word Afrikaansch (now spelled Afrikaans)[18] meaning "African".[19] It was previously referred to as "Cape Dutch" (Kaap-Hollands/Kaap-Nederlands), a term also used to refer to the early Cape settlers collectively, or the derogatory "kitchen Dutch" (kombuistaal) from its use by slaves of colonial settlers "in the kitchen".

History

Origin

The Afrikaans language arose in the Dutch Cape Colony, through a gradual divergence from European Dutch dialects, during the course of the 18th century.[20][21] As early as the mid-18th century and as recently as the mid-20th century, Afrikaans was known in standard Dutch as a "kitchen language" (Afrikaans: kombuistaal), lacking the prestige accorded, for example, even by the educational system in Africa, to languages spoken outside Africa. Other early epithets setting apart Kaaps Hollands ("Cape Dutch", i.e. Afrikaans) as putatively beneath official Dutch standards included geradbraakt, gebroken and onbeschaafd Hollands ("mutilated/broken/uncivilised Dutch"), as well as verkeerd Nederlands ("incorrect Dutch").[22][23]

| 'Hottentot Dutch' | |

|---|---|

Dutch-based pidgin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

| Glottolog | hott1234 |

Den Besten theorises that modern Standard Afrikaans derives from two sources:[24]

- Cape Dutch, a direct transplantation of European Dutch to Southern Africa, and

- 'Hottentot Dutch',[25] a pidgin that descended from 'Foreigner Talk' and ultimately from the Dutch pidgin spoken by slaves, via a hypothetical Dutch creole.

Thus in his view Afrikaans is neither a creole nor a direct descendant of Dutch, but a fusion of two transmission pathways.

Development

Most of the first settlers whose descendants today are the Afrikaners were from the United Provinces (now Netherlands),[26] with up to one-sixth of the community of French Huguenot origin, and a seventh from Germany.[27]

African and Asian workers, Cape Coloured children of European settlers and Khoikhoi women,[28] and slaves contributed to the development of Afrikaans. The slave population was made up of people from East Africa, West Africa, India, Madagascar, and the Dutch East Indies (modern Indonesia).[29] A number were also indigenous Khoisan people, who were valued as interpreters, domestic servants, and labourers. Many free and enslaved women married or cohabited with the male Dutch settlers. M. F. Valkhoff argued that 75% of children born to female slaves in the Dutch Cape Colony between 1652 and 1672 had a Dutch father.[30] Sarah Grey Thomason and Terrence Kaufman argue that Afrikaans' development as a separate language was "heavily conditioned by nonwhites who learned Dutch imperfectly as a second language."[31]

Beginning in about 1815, Afrikaans started to replace Malay as the language of instruction in Muslim schools in South Africa, written with the Arabic alphabet: see Arabic Afrikaans. Later, Afrikaans, now written with the Latin script, started to appear in newspapers and political and religious works in around 1850 (alongside the already established Dutch).[20]

In 1875, a group of Afrikaans-speakers from the Cape formed the Genootskap vir Regte Afrikaaners ("Society for Real Afrikaners"),[20] and published a number of books in Afrikaans including grammars, dictionaries, religious materials and histories.

Until the early 20th century, Afrikaans was considered a Dutch dialect, alongside Standard Dutch, which it eventually replaced as an official language.[32] Before the Boer wars, "and indeed for some time afterwards, Afrikaans was regarded as inappropriate for educated discourse. Rather, Afrikaans was described derogatorily as 'a kitchen language' or 'a bastard jargon', suitable for communication mainly between the Boers and their servants."[33]

Recognition

In 1925, Afrikaans was recognised by the South African government as a distinct language, rather than simply a vernacular of Dutch.[20] On 8 May 1925, twenty-three years after the Second Boer War ended,[33] the Official Languages of the Union Act of 1925 was passed—mostly due to the efforts of the Afrikaans-language movement—at a joint sitting of the House of Assembly and the Senate, in which the Afrikaans language was declared a variety of Dutch.[34] The Constitution of 1961 reversed the position of Afrikaans and Dutch, so that English and Afrikaans were the official languages, and Afrikaans was deemed to include Dutch. The Constitution of 1983 removed any mention of Dutch altogether.

The Afrikaans Language Monument is located on a hill overlooking Paarl in the Western Cape Province. Officially opened on 10 October 1975,[35] it was erected on the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Society of Real Afrikaners,[36] and the 50th anniversary of Afrikaans being declared an official language of South Africa in distinction to Dutch.

Standardisation

The earliest Afrikaans texts were some doggerel verse from 1795 and a dialogue transcribed by a Dutch traveller in 1825. Afrikaans used the Latin alphabet around this time, although the Cape Muslim community used the Arabic script. In 1861, L.H. Meurant published his Zamenspraak tusschen Klaas Waarzegger en Jan Twyfelaar ("Conversation between Nicholas Truthsayer and John Doubter"), which is considered to be the first book published in Afrikaans.[37]

The first grammar book was published in 1876; a bilingual dictionary was later published in 1902. The main modern Afrikaans dictionary in use is the Verklarende Handwoordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (HAT). A new authoritative dictionary, called Woordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (WAT), was under development as of 2018. The official orthography of Afrikaans is the Afrikaanse Woordelys en Spelreëls, compiled by Die Taalkommissie.[37]

The Afrikaans Bible

The Afrikaners primarily were Protestants, of the Dutch Reformed Church of the 17th century. Their religious practices would later be influenced in South Africa by British ministries during the 1800s.[38] A landmark in the development of the language was the translation of the whole Bible into Afrikaans. While significant advances had been made in the textual criticism of the Bible, especially the Greek New Testament, the 1933 translation followed the Textus Receptus and was closely akin to the Statenbijbel. Before this, most Cape Dutch-Afrikaans speakers had to rely on the Dutch Statenbijbel. This Statenvertaling had its origins with the Synod of Dordrecht of 1618 and was thus in an archaic form of Dutch. This was hard for Dutch speakers to understand, and increasingly unintelligible for Afrikaans speakers.

C. P. Hoogehout, Arnoldus Pannevis, and Stephanus Jacobus du Toit were the first Afrikaans Bible translators. Important landmarks in the translation of the Scriptures were in 1878 with C. P. Hoogehout's translation of the Evangelie volgens Markus (Gospel of Mark, lit. Gospel according to Mark); however, this translation was never published. The manuscript is to be found in the South African National Library, Cape Town.

The first official translation of the entire Bible into Afrikaans was in 1933 by J. D. du Toit, E. E. van Rooyen, J. D. Kestell, H. C. M. Fourie, and BB Keet.[39][40] This monumental work established Afrikaans as 'n suiwer en ordentlike taal, that is "a pure and proper language" for religious purposes, especially amongst the deeply Calvinist Afrikaans religious community that previously had been sceptical of a Bible translation that varied from the Dutch version that they were used to.

In 1983, a fresh translation marked the 50th anniversary of the 1933 version and provided a much-needed revision. The final editing of this edition was done by E. P. Groenewald, A. H. van Zyl, P. A. Verhoef, J. L. Helberg and W. Kempen. This translation was influenced by Eugene Nida's theory of dynamic equivalence which focused on finding the nearest equivalent in the receptor language to the idea that the Greek, Hebrew or Aramaic wanted to convey.

A new translation, Die Bybel: 'n Direkte Vertaling was released in November 2020. It is the first truly ecumenical translation of the Bible in Afrikaans as translators from various churches, including the Roman Catholic and Anglican Churches, were involved.[41]

Various commercial translations of the Bible in Afrikaans have also appeared since the 1990s, such as Die Boodskap and the Nuwe Lewende Vertaling. Most of these translations were published by Christelike Uitgewersmaatskappy (CUM).

Classification

Afrikaans descended from Dutch dialects in the 17th century. It belongs to a West Germanic sub-group, the Low Franconian languages.[42] Other West Germanic languages related to Afrikaans are German, English, the Frisian languages, and the unstandardised languages Low German and Yiddish.

Geographic distribution

Statistics

| Country | Speakers | Percentage of speakers | Year | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 650 | 0.001% | 2019 | [43] | |

| 49,375 | 0.68% | 2021 | [44] | |

| 8,082 | 0.11% | 2011 | [44] | |

| 23,410 | 0.32% | 2016 | [45] | |

| 11,247 | 0.16% | 2011 | [46] | |

| 122 | 0.002% | 2021 | [47] | |

| 2,228 | 0.03% | 2016 | [48] | |

| 36 | 0.000005% | 2011 | [44] | |

| 219,760 | 3.05% | 2011 | [44] | |

| 36,966 | 0.51% | 2018 | [49] | |

| 6,855,082 | 94.66% | 2011 | [44] | |

| 28,406 | 0.39% | 2016 | [50] | |

| Total | 7,211,537 |

Sociolinguistics

Some state that instead of Afrikaners, which refers to an ethnic group, the terms Afrikaanses or Afrikaanssprekendes (lit. Afrikaans speakers) should be used for people of any ethnic origin who speak Afrikaans. Linguistic identity has not yet established which terms shall prevail, and all three are used in common parlance.[51]

Afrikaans is also widely spoken in Namibia. Before independence, Afrikaans had equal status with German as an official language. Since independence in 1990, Afrikaans has had constitutional recognition as a national, but not official, language.[52][53] There is a much smaller number of Afrikaans speakers among Zimbabwe's white minority, as most have left the country since 1980. Afrikaans was also a medium of instruction for schools in Bophuthatswana, an Apartheid-era Bantustan.[54] Eldoret in Kenya was founded by Afrikaners.[55]

Many South Africans living and working in Belgium, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States, Israel, the UAE and Kuwait are also Afrikaans speakers. They have access to Afrikaans websites, news sites such as Netwerk24.com and Sake24, and radio broadcasts over the web, such as those from Radio Sonder Grense, Bokradio and Radio Pretoria. There are also many artists that tour to bring Afrikaans to the emigrants.

Afrikaans has been influential in the development of South African English. Many Afrikaans loanwords have found their way into South African English, such as bakkie ("pickup truck"), braai ("barbecue"), naartjie ("tangerine"), tekkies (American "sneakers", British "trainers", Canadian "runners"). A few words in standard English are derived from Afrikaans, such as aardvark (lit. "earth pig"), trek ("pioneering journey", in Afrikaans lit. "pull" but used also for "migrate"), spoor ("animal track"), veld ("Southern African grassland" in Afrikaans, lit. "field"), commando from Afrikaans kommando meaning small fighting unit, boomslang ("tree snake") and apartheid ("segregation"; more accurately "apartness" or "the state or condition of being apart").

In 1976, secondary-school pupils in Soweto began a rebellion in response to the government's decision that Afrikaans be used as the language of instruction for half the subjects taught in non-White schools (with English continuing for the other half). Although English is the mother tongue of only 8.2% of the population, it is the language most widely understood, and the second language of a majority of South Africans.[56] Afrikaans is more widely spoken than English in the Northern and Western Cape provinces, several hundred kilometres from Soweto.[57] The Black community's opposition to Afrikaans and preference for continuing English instruction was underlined when the government rescinded the policy one month after the uprising: 96% of Black schools chose English (over Afrikaans or native languages) as the language of instruction.[57] Afrikaans-medium schools were also accused of using language policy to deter black African parents.[58] Some of these parents, in part supported by provincial departments of education, initiated litigation which enabled enrolment with English as language of instruction. By 2006 there were 300 single-medium Afrikaans schools, compared to 2,500 in 1994, after most converted to dual-medium education.[58] Due to Afrikaans being viewed as the "language of the white oppressor" by some, pressure has been increased to remove Afrikaans as a teaching language in South African universities, resulting in bloody student protests in 2015.[59][60][61]

Under South Africa's Constitution of 1996, Afrikaans remains an official language, and has equal status to English and nine other languages. The new policy means that the use of Afrikaans is now often reduced in favour of English, or to accommodate the other official languages. In 1996, for example, the South African Broadcasting Corporation reduced the amount of television airtime in Afrikaans, while South African Airways dropped its Afrikaans name Suid-Afrikaanse Lugdiens from its livery. Similarly, South Africa's diplomatic missions overseas now display the name of the country only in English and their host country's language, and not in Afrikaans. Meanwhile, the constitution of the Western Cape, which went into effect in 1998, declares Afrikaans to be an official language of the province alongside English and Xhosa.[62]

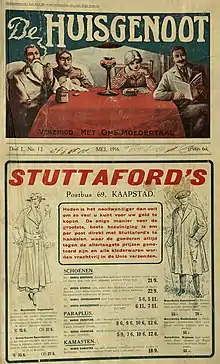

In spite of these moves, the language has remained strong, and Afrikaans newspapers and magazines continue to have large circulation figures. Indeed, the Afrikaans-language general-interest family magazine Huisgenoot has the largest readership of any magazine in the country.[63] In addition, a pay-TV channel in Afrikaans called KykNet was launched in 1999, and an Afrikaans music channel, MK (Musiek kanaal) (lit. 'Music Channel'), in 2005. A large number of Afrikaans books are still published every year, mainly by the publishers Human & Rousseau, Tafelberg Uitgewers, Struik, and Protea Boekhuis. The Afrikaans film trilogy Bakgat (first released in 2008) caused a reawakening of the Afrikaans film industry (which had been moribund since the mid to late 1990s ) and Belgian-born singer Karen Zoid's debut single "Afrikaners is Plesierig" (released 2001) caused a resurgence in the Afrikaans music industry, as well as giving rise to the Afrikaans Rock genre.

Afrikaans has two monuments erected in its honour. The first was erected in Burgersdorp, South Africa, in 1893, and the second, nowadays better-known Afrikaans Language Monument (Afrikaanse Taalmonument), was built in Paarl, South Africa, in 1975.

When the British design magazine Wallpaper described Afrikaans as "one of the world's ugliest languages" in its September 2005 article about the monument,[64] South African billionaire Johann Rupert (chairman of the Richemont Group), responded by withdrawing advertising for brands such as Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, Montblanc and Alfred Dunhill from the magazine.[65] The author of the article, Bronwyn Davies, was an English-speaking South African.

Mutual intelligibility with Dutch

An estimated 90 to 95% of the Afrikaans lexicon is ultimately of Dutch origin,[66][67][68] and there are few lexical differences between the two languages.[69] Afrikaans has a considerably more regular morphology,[70] grammar, and spelling.[71] There is a high degree of mutual intelligibility between the two languages,[70][72][73] particularly in written form.[71][74][75]

Afrikaans acquired some lexical and syntactical borrowings from other languages such as Malay, Khoisan languages, Portuguese,[76] and Bantu languages,[77] and Afrikaans has also been significantly influenced by South African English.[78] Dutch speakers are confronted with fewer non-cognates when listening to Afrikaans than the other way round.[75] Mutual intelligibility thus tends to be asymmetrical, as it is easier for Dutch speakers to understand Afrikaans than for Afrikaans speakers to understand Dutch.[75]

In general, mutual intelligibility between Dutch and Afrikaans is far better than between Dutch and Frisian[79] or between Danish and Swedish.[75] The South African poet writer Breyten Breytenbach, attempting to visualise the language distance for Anglophones once remarked that the differences between (Standard) Dutch and Afrikaans are comparable to those between the Received Pronunciation and Southern American English.[80]

Current status

| Province | 1996[81] | 2001[81] | 2011[81] | 2016[81] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Western Cape | 58.5% | 55.3% | 49.7% | 45.7% |

| Eastern Cape | 9.8% | 9.6% | 10.6% | 10.1% |

| Northern Cape | 57.2% | 56.6% | 53.8% | 55.7% |

| Free State | 14.4% | 11.9% | 12.7% | 10.7% |

| KwaZulu-Natal | 1.6% | 1.5% | 1.6% | 1.0% |

| North West | 8.8% | 8.8% | 9.0% | 7.0% |

| Gauteng | 15.6% | 13.6% | 12.4% | 9.9% |

| Mpumalanga | 7.1% | 5.5% | 7.2% | 4.8% |

| Limpopo | 2.6% | 2.6% | 2.6% | 2.2% |

| 14.4%[82] | 13.3%[83] | 13.5%[16] | 12.1% |

Post-apartheid South Africa has seen a loss of preferential treatment by the government for Afrikaans, in terms of education, social events, media (TV and radio), and general status throughout the country, given that it now shares its place as official language with ten other languages. Nevertheless, Afrikaans remains more prevalent in the media – radio, newspapers and television[84] – than any of the other official languages, except English. More than 300 book titles in Afrikaans are published annually.[85] South African census figures suggest a growing number of speakers in all nine provinces, a total of 6.85 million in 2011 compared to 5.98 million a decade earlier.[86] The South African Institute of Race Relations (SAIRR) projects that a growing majority will be Coloured Afrikaans speakers.[87] Afrikaans speakers experience higher employment rates than other South African language groups, though as of 2012 half a million were unemployed.[86]

Despite the challenges of demotion and emigration that it faces in South Africa, the Afrikaans vernacular remains competitive, being popular in DSTV pay channels and several internet sites, while generating high newspaper and music CD sales. A resurgence in Afrikaans popular music since the late 1990s has invigorated the language, especially among a younger generation of South Africans. A recent trend is the increased availability of pre-school educational CDs and DVDs. Such media also prove popular with the extensive Afrikaans-speaking emigrant communities who seek to retain language proficiency in a household context.

Afrikaans-language cinema showed signs of new vigour in the early 21st century. The 2007 film Ouma se slim kind, the first full-length Afrikaans movie since Paljas in 1998, is seen as the dawn of a new era in Afrikaans cinema. Several short films have been created and more feature-length movies, such as Poena is Koning and Bakgat (both in 2008) have been produced, besides the 2011 Afrikaans-language film Skoonheid, which was the first Afrikaans film to screen at the Cannes Film Festival. The film Platteland was also released in 2011.[88] The Afrikaans film industry started gaining international recognition via the likes of big Afrikaans Hollywood film stars, like Charlize Theron (Monster) and Sharlto Copley (District 9) promoting their mother tongue.

SABC3 announced early in 2009 that it would increase Afrikaans programming due to the "growing Afrikaans-language market and [their] need for working capital as Afrikaans advertising is the only advertising that sells in the current South African television market". In April 2009, SABC3 started screening several Afrikaans-language programmes.[89] Further latent support for the language derives from its de-politicised image in the eyes of younger-generation South Africans, who less and less often view it as "the language of the oppressor". Indeed, there is a groundswell movement within Afrikaans to be inclusive, and to promote itself along with the other indigenous official languages. In Namibia, the percentage of Afrikaans speakers declined from 11.4% (2001 Census) to 10.4% (2011 Census). The major concentrations are in Hardap (41.0%), ǁKaras (36.1%), Erongo (20.5%), Khomas (18.5%), Omaheke (10.0%), Otjozondjupa (9.4%), Kunene (4.2%), and Oshikoto (2.3%).[90]

Many native speakers of Bantu languages and English also speak Afrikaans as a second language. It is widely taught in South African schools, with about 10.3 million second-language students.[1] Even in KwaZulu-Natal (where there are relatively few Afrikaans home-speakers), the majority of pupils opt for Afrikaans as their first additional language because it is regarded as easier than Zulu.[91]

Afrikaans is offered at many universities outside South Africa, including in the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany, Poland, Russia and the United States.[92]

Grammar

In Afrikaans grammar, there is no distinction between the infinitive and present forms of verbs, with the exception of the verbs 'to be' and 'to have':

| infinitive form | present indicative form | Dutch | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| wees | is | zijn or wezen | be |

| hê | het | hebben | have |

In addition, verbs do not conjugate differently depending on the subject. For example,

| Afrikaans | Dutch | English |

|---|---|---|

| ek is | ik ben | I am |

| jy/u is | jij/u bent | you are (sing.) |

| hy/sy/dit is | hij/zij/het is | he/she/it is |

| ons is | wij zijn | we are |

| julle is | jullie zijn | you are (plur.) |

| hulle is | zij zijn | they are |

Only a handful of Afrikaans verbs have a preterite, namely the auxiliary wees ("to be"), the modal verbs, and the verb dink ("to think"). The preterite of mag ("may") is rare in contemporary Afrikaans.

| Afrikaans | Dutch | English | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| present | past | present | past | present | past |

| ek is | ek was | ik ben | ik was | I am | I was |

| ek kan | ek kon | ik kan | ik kon | I can | I could |

| ek moet | ek moes | ik moet | ik moest | I must | (I had to) |

| ek wil | ek wou | ik wil | ik wilde/wou | I want to | I wanted to |

| ek sal | ek sou | ik zal | ik zou | I shall | I should |

| ek mag | (ek mog) | ik mag | ik mocht | I may | I might |

| ek dink | ek dog | ik denk | ik dacht | I think | I thought |

All other verbs use the perfect tense, het + past participle (ge-), for the past. Therefore, there is no distinction in Afrikaans between I drank and I have drunk. (In colloquial German, the past tense is also often replaced with the perfect.)

| Afrikaans | Dutch | English |

|---|---|---|

| ek het gedrink | ik dronk | I drank |

| ik heb gedronken | I have drunk |

When telling a longer story, Afrikaans speakers usually avoid the perfect and simply use the present tense, or historical present tense instead (as is possible, but less common, in English as well).

A particular feature of Afrikaans is its use of the double negative; it is classified in Afrikaans as ontkennende vorm and is something that is absent from the other West Germanic standard languages. For example,

- Afrikaans: Hy kan nie Afrikaans praat nie, lit. 'He can not Afrikaans speak not'

- Dutch: Hij spreekt geen Afrikaans.

- English: He can not speak Afrikaans. / He can't speak Afrikaans.

Both French and San origins have been suggested for double negation in Afrikaans. While double negation is still found in Low Franconian dialects in West Flanders and in some "isolated" villages in the centre of the Netherlands (such as Garderen), it takes a different form, which is not found in Afrikaans. The following is an example:

- Afrikaans: Ek wil nie dit doen nie.* (lit. I want not this do not.)

- Dutch: Ik wil dit niet doen.

- English: I do not want to do this.

* Compare with Ek wil dit nie doen nie, which changes the meaning to "I want not to do this." Whereas Ek wil nie dit doen nie emphasizes a lack of desire to act, Ek wil dit nie doen nie emphasizes the act itself.

The -ne was the Middle Dutch way to negate but it has been suggested that since -ne became highly non-voiced, nie or niet was needed to complement the -ne. With time the -ne disappeared in most Dutch dialects.

The double negative construction has been fully grammaticalised in standard Afrikaans and its proper use follows a set of fairly complex rules as the examples below show:

| Afrikaans | Dutch (literally translated) | More correct Dutch | Literal English | Idiomatic English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ek het (nie) geweet dat hy (nie) sou kom (nie). | Ik heb (niet) geweten dat hij (niet) zou komen. | Ik wist (niet) dat hij (niet) zou komen. | I did (not) know that he would (not) come. | I did (not) know that he was (not) going to come. |

| Hy sal nie kom nie, want hy is siek.[note 4] | Hij zal niet komen, want hij is ziek. | Hij komt niet, want hij is ziek. | He will not come, as he is sick. | He is sick and is not going to come. |

| Dis (Dit is) nie so moeilik om Afrikaans te leer nie. | Het is niet zo moeilijk (om) Afrikaans te leren. | It is not so difficult to learn Afrikaans. | ||

A notable exception to this is the use of the negating grammar form that coincides with negating the English present participle. In this case there is only a single negation.

- Afrikaans: Hy is in die hospitaal, maar hy eet nie.

- Dutch: Hij is in het ziekenhuis, maar hij eet niet.

- English: He is in [the] hospital, though he eats not.

Certain words in Afrikaans would be contracted. For example, moet nie, which literally means "must not", usually becomes moenie; although one does not have to write or say it like this, virtually all Afrikaans speakers will change the two words to moenie in the same way as do not is contracted to don't in English.

The Dutch word het ("it" in English) does not correspond to het in Afrikaans. The Dutch words corresponding to Afrikaans het are heb, hebt, heeft and hebben.

| Afrikaans | Dutch | English |

|---|---|---|

| het | heb, hebt, heeft, hebben | have, has |

| die | de, het | the |

| dit | het | it |

Phonology

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| unrounded | rounded | unrounded | rounded | |||||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| Close | i | (iː) | y | yː | u | (uː) | ||||

| Mid | e | eː | ə | (əː) | œ | (œː) | o | (oː) | ||

| Near-open | (æ) | (æː) | ||||||||

| Open | a | ɑː | ||||||||

- As phonemes, /iː/ and /uː/ occur only in the words spieël /spiːl/ 'mirror' and koeël /kuːl/ 'bullet', which used to be pronounced with sequences /i.ə/ and /u.ə/, respectively. In other cases, [iː] and [uː] occur as allophones of, respectively, /i/ and /u/ before /r/.[95]

- /y/ is phonetically long [yː] before /r/.[96]

- /əː/ is always stressed and occurs only in the word wîe 'wedges'.[97]

- The closest unrounded counterparts of /œ, œː/ are central /ə, əː/, rather than front /e, eː/.[98]

- /œː, oː/ occur only in a few words.[99]

- [æ] occurs as an allophone of /e/ before /k, χ, l, r/, though this occurs primarily dialectally, most commonly in the former Transvaal and Free State provinces.[100]

Diphthongs

| Starting point | Ending point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Central | Back | ||

| Mid | unrounded | ɪø, əi | ɪə | |

| rounded | œi, ɔi | ʊə | œu | |

| Open | unrounded | ai, ɑːi | ||

- /ɔi, ai/ occur mainly in loanwords.[103]

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Dorsal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | t͡ʃ | k | |

| voiced | b | d | (d͡ʒ) | (ɡ) | ||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ (ɹ̠̊˔) | χ | |

| voiced | v | (z) | ʒ | ɦ | ||

| Approximant | l | j | ||||

| Rhotic | r ~ ɾ ~ ʀ ~ ʁ | |||||

- All obstruents at the ends of words are devoiced, so that e.g. a final /d/ is realized as [t].[104]

- /ɡ, dʒ, z/ occur only in loanwords. [ɡ] is also an allophone of /χ/ in some environments.[105]

- /χ/ is most often uvular [χ ~ ʀ̥].[106][107][108] Velar [x] occurs only in some speakers.[107]

- The rhotic is usually an alveolar trill [r] or tap [ɾ].[109] In some parts of the former Cape Province, it is realized uvularly, either as a trill [ʀ] or a fricative [ʁ].[110]

Dialects

Following early dialectal studies of Afrikaans, it was theorised that three main historical dialects probably existed after the Great Trek in the 1830s. These dialects are the Northern Cape, Western Cape, and Eastern Cape dialects.[111] Northern Cape dialect may have resulted from contact between Dutch settlers and the Khoekhoe people between the Great Karoo and the Kunene, and Eastern Cape dialect between the Dutch and the Xhosa. Remnants of these dialects still remain in present-day Afrikaans, although the standardising effect of Standard Afrikaans has contributed to a great levelling of differences in modern times.[112]

There is also a prison cant, known as Sabela, which is based on Afrikaans, yet heavily influenced by Zulu. This language is used as a secret language in prison and is taught to initiates.[112]

Kaapse Afrikaans

The term Kaapse Afrikaans (transl. Cape Afrikaans) is sometimes erroneously used to refer to the entire Western Cape dialect; it is more commonly used for a particular sociolect spoken in the Cape Peninsula of South Africa. Kaapse Afrikaans was once spoken by all population groups. However, it became increasingly restricted to the Cape Coloured ethnic group in Cape Town and surrounds. Kaapse Afrikaans is still understood by the large majority of native Afrikaans speakers in South Africa.

Kaapse Afrikaans preserves some features more similar to Dutch than to Afrikaans.[113]

- The first-person singular pronoun ik as in Dutch as opposed to Afrikaans ek.

- The diminutive endings -tje, pronounced as in Dutch and not as /ki/ as in Afrikaans.

- The use of the form seg (compare Dutch zegt) as opposed to Afrikaans sê.

Kaapse Afrikaans has some other features not typically found in Afrikaans.

- The pronunciation of j, normally /j/ as in Dutch is often a /dz/. This is the strongest feature of Kaapse Afrikaans.

- The insertion of /j/ after /s/, /t/ and /k/ when followed by /e/, e.g. kjen as opposed to Standard Afrikaans ken.

Kaapse Afrikaans is also characterised by much code-switching between South African English and Afrikaans, especially in the inner-city and areas in Cape Town with lower socio-economic status.

An example of characteristic Kaapse Afrikaans:

- Dutch: En ik zeg (tegen) jullie: wat zoeken jullie hier bij mij? Ik zoek jullie niet! Nee, ga nu weg!

- Kaapse Afrikaans: En ik seg ve' djille, wat soek djille hie' by my? Ik soek'ie ve' djille nie! Nei, gaat nou weg!

- Afrikaans: En ek sê vir julle, wat soek julle hier by my? Ek soek julle nie! Nee, gaan nou weg!

- English (literal): And I say to you, what seek you here by me? I seek you not! No, go now away!

- English: And I'm telling you, what are you looking for here? I don't want you! No, go away now!

Oranjerivierafrikaans

The term Oranjerivierafrikaans ("Afrikaans of the Orange River") is sometimes erroneously used to refer to the Northern Cape dialect; it is more commonly used for the regional peculiarities of standard Afrikaans spoken in the Upington/Orange River wine district of South Africa.

Some of the characteristics of Oranjerivierafrikaans are the plural form -goed (Ma-goed, meneergoed), variant pronunciation such as in kjerk ("Church") and gjeld ("money") and the ending -se, which indicates possession.

Patagonian Afrikaans dialect

A distinct dialect of Afrikaans is spoken by the 650-strong South African community of Argentina, in the region of Patagonia.[114]

Influences on Afrikaans from other languages

Malay

Due to the early settlement of a Cape Malay community in Cape Town, who are now known as Coloureds, numerous Classical Malay words were brought into Afrikaans. Some of these words entered Dutch via people arriving from what is now known as Indonesia as part of their colonial heritage. Malay words in Afrikaans include:[115]

- baie, which means 'very'/'much'/'many' (from banyak) is a very commonly used Afrikaans word, different from its Dutch equivalent veel or erg.

- baadjie, Afrikaans for jacket (from baju, ultimately from Persian), used where Dutch would use jas or vest. The word baadje in Dutch is now considered archaic and only used in written, literary texts.

- bobotie, a traditional Cape-Malay dish, made from spiced minced meat baked with an egg-based topping.

- piesang, which means banana. This is different from the common Dutch word banaan. The Indonesian word pisang is also used in Dutch, though usage is more common.

- piering, which means saucer (from piring, also from Persian).

Portuguese

Some words originally came from Portuguese such as sambreel ("umbrella") from the Portuguese sombreiro, kraal ("pen/cattle enclosure") from the Portuguese curral and mielie ("corn", from milho). Some of these words also exist in Dutch, like sambreel "parasol",[116] though usage is less common and meanings can slightly differ.

Khoisan languages

- dagga, meaning cannabis[115]

- geitjie, meaning lizard, diminutive adapted from a Khoekhoe word[117]

- gogga, meaning insect, from the Khoisan xo-xo

- karos, blanket of animal hides

- kierie, walking stick from Khoekhoe[117]

Some of these words also exist in Dutch, though with a more specific meaning: assegaai for example means "South-African tribal javelin"[118] and karos means "South-African tribal blanket of animal hides".[119]

Bantu languages

Loanwords from Bantu languages in Afrikaans include the names of indigenous birds, such as mahem and sakaboela, and indigenous plants, such as maroela and tamboekie(gras).[120]

- fundi, from the Zulu word umfundi meaning "scholar" or "student",[121] but used to mean someone who is a student of/expert on a certain subject, i.e. He is a language fundi.

- lobola, meaning bride price, from (and referring to) lobolo of the Nguni languages[122]

- mahem, the grey crowned crane, known in Latin as Balearica regulorum

- maroela, medium-sized dioecious tree known in Latin as Sclerocarya birrea[123]

- tamboekiegras, species of thatching grass known as Hyparrhenia[124]

- tambotie, deciduous tree also known by its Latin name, Spirostachys africana[125]

- tjaila / tjailatyd, an adaption of the word chaile, meaning "to go home" or "to knock off (from work)".[126]

French

The revoking of the Edict of Nantes on 22 October 1685 was a milestone in the history of South Africa, for it marked the beginning of the great Huguenot exodus from France. It is estimated that between 250,000 and 300,000 Protestants left France between 1685 and 1700; out of these, according to Louvois, 100,000 had received military training. A measure of the calibre of these immigrants and of their acceptance by host countries (in particular South Africa) is given by H. V. Morton in his book: In Search of South Africa (London, 1948). The Huguenots were responsible for a great linguistic contribution to Afrikaans, particularly in terms of military terminology as many of them fought on the battlefields during the wars of the Great Trek.

Most of the words in this list are descendants from Dutch borrowings from French, Old French or Latin, and are not direct influences from French on Afrikaans.

| Afrikaans | Dutch | French | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| advies | advies | avis | advice |

| alarm | alarm | alarme | alarm |

| ammunisie | ammunitie, munitie | munition | ammunition |

| amusant | amusant | amusant | funny |

| artillerie | artillerie | artillerie | artillery |

| ateljee | atelier | atelier | studio |

| bagasie | bagage | bagage | luggage |

| bastion | bastion | bastion | bastion |

| bataljon | bataljon | bataillon | battalion |

| battery | batterij | batterie | battery |

| biblioteek | bibliotheek | bibliothèque | library |

| faktuur | factuur | facture | invoice |

| fort | fort | fort | fort |

| frikkadel | frikadel | fricadelle | meatball |

| garnisoen | garnizoen | garnison | garrison |

| generaal | generaal | général | general |

| granaat | granaat | grenade | grenade |

| infanterie | infanterie | infanterie | infantry |

| interessant | interessant | intéressant | interesting |

| kaliber | kaliber | calibre | calibre |

| kanon | kanon | canon | canon |

| kanonnier | kanonnier | canonier | gunner |

| kardoes | kardoes, cartouche | cartouche | cartridge |

| kaptein | kapitein | capitaine | captain |

| kolonel | kolonel | colonel | colonel |

| kommandeur | commandeur | commandeur | commander |

| kwartier | kwartier | quartier | quarter |

| lieutenant | lieutenant | lieutenant | lieutenant |

| magasyn | magazijn | magasin | magazine |

| manier | manier | manière | way |

| marsjeer | marcheer, marcheren | marcher | (to) march |

| meubels | meubels | meubles | furniture |

| militêr | militair | militaire | militarily |

| morsel | morzel | morceau | piece |

| mortier | mortier | mortier | mortar |

| muit | muit, muiten | mutiner | (to) mutiny |

| musket | musket | mousquet | musket |

| muur | muur | mur | wall |

| myn | mijn | mine | mine |

| offisier | officier | officier | officer |

| orde | orde | ordre | order |

| papier | papier | papier | paper |

| pionier | pionier | pionnier | pioneer |

| plafon | plafond | plafond | ceiling |

| plat | plat | plat | flat |

| pont | pont | pont | ferry |

| provoos | provoost | prévôt | chief |

| rondte | rondte, ronde | ronde | round |

| salvo | salvo | salve | salvo |

| soldaat | soldaat | soldat | soldier |

| tante | tante | tante | aunt |

| tapyt | tapijt | tapis | carpet |

| tros | tros | trousse | bunch |

Orthography

The Afrikaans writing system is based on Dutch, using the 26 letters of the ISO basic Latin alphabet, plus 16 additional vowels with diacritics. The hyphen (e.g. in a compound like see-eend 'sea duck'), apostrophe (e.g. ma's 'mothers'), and a whitespace character (e.g. in multi-word units like Dooie See 'Dead Sea') is part of the orthography of words, while the indefinite article ʼn is a ligature. All the alphabet letters, including those with diacritics, have capital letters as allographs; the ʼn does not have a capital letter allograph. This means that Afrikaans has 88 graphemes with allographs in total.

| Majuscule forms (also called uppercase or capital letters) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Á | Ä | B | C | D | E | É | È | Ê | Ë | F | G | H | I | Í | Î | Ï | J | K | L | M | N | O | Ó | Ô | Ö | P | Q | R | S | T | U | Ú | Û | Ü | V | W | X | Y | Ý | Z | |

| Minuscule forms (also called lowercase or small letters) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| a | á | ä | b | c | d | e | é | è | ê | ë | f | g | h | i | í | î | ï | j | k | l | m | n | ʼn | o | ó | ô | ö | p | q | r | s | t | u | ú | û | ü | v | w | x | y | ý | z |

In Afrikaans, many consonants are dropped from the earlier Dutch spelling. For example, slechts ('only') in Dutch becomes slegs in Afrikaans. Also, Afrikaans and some Dutch dialects make no distinction between /s/ and /z/, having merged the latter into the former; while the word for "south" is written zuid in Dutch, it is spelled suid in Afrikaans (as well as dialectal Dutch writings) to represent this merger. Similarly, the Dutch digraph ij, normally pronounced as /ɛi/, corresponds to Afrikaans y, except where it replaces the Dutch suffix –lijk which is pronounced as /lək/, as in waarschijnlijk > waarskynlik.

Another difference is the indefinite article, 'n in Afrikaans and een in Dutch. "A book" is 'n boek in Afrikaans, whereas it is either een boek or 'n boek in Dutch. This 'n is usually pronounced as just a weak vowel, [ə], just like English "a".

The diminutive suffix in Afrikaans is -tjie, -djie or -ie, whereas in Dutch it is -tje or dje, hence a "bit" is ʼn bietjie in Afrikaans and beetje in Dutch.

The letters c, q, x, and z occur almost exclusively in borrowings from French, English, Greek and Latin. This is usually because words that had c and ch in the original Dutch are spelled with k and g, respectively, in Afrikaans. Similarly original qu and x are most often spelt kw and ks, respectively. For example, ekwatoriaal instead of equatoriaal, and ekskuus instead of excuus.

The vowels with diacritics in non-loanword Afrikaans are: á, ä, é, è, ê, ë, í, î, ï, ó, ô, ö, ú, û, ü, ý. Diacritics are ignored when alphabetising, though they are still important, even when typing the diacritic forms may be difficult. For example, geëet ("ate") instead of the 3 e's alongside each other: *geeet, which can never occur in Afrikaans, or sê, which translates to "say", whereas se is a possessive form. The acute's (á, é, í, ó, ú, ý) primary function is to place emphasis on a word (i.e. for emphatic reasons), by adding it to the emphasised syllable of the word. For example, sál ("will" (verb)), néé ('no'), móét ("must"), hý ("he"), gewéét ("knew"). The acute is only placed on the i if it is the only vowel in the emphasised word: wil ('want' (verb)) becomes wíl, but lui ('lazy') becomes lúi. Only a few non-loan words are spelled with acutes, e.g. dié ('this'), ná ('after'), óf ... óf ('either ... or'), nóg ... nóg ('neither ... nor'), etc. Only four non-loan words are spelled with the grave: nè ('yes?', 'right?', 'eh?'), dè ('here, take this!' or '[this is] yours!'), hè ('huh?', 'what?', 'eh?'), and appèl ('(formal) appeal' (noun)).

Initial apostrophes

A few short words in Afrikaans take initial apostrophes. In modern Afrikaans, these words are always written in lower case (except if the entire line is uppercase), and if they occur at the beginning of a sentence, the next word is capitalised. Three examples of such apostrophed words are 'k, 't, 'n. The last (the indefinite article) is the only apostrophed word that is common in modern written Afrikaans, since the other examples are shortened versions of other words (ek and het, respectively) and are rarely found outside of a poetic context.[127]

Here are a few examples:

| Apostrophed version | Usual version | Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 'k 't Dit gesê | Ek het dit gesê | I said it | Uncommon, more common: Ek't dit gesê |

| 't Jy dit geëet? | Het jy dit geëet? | Did you eat it? | Extremely uncommon |

| 'n Man loop daar | A man walks there | Standard Afrikaans pronounces 'n as a schwa vowel. |

The apostrophe and the following letter are regarded as two separate characters, and are never written using a single glyph, although a single character variant of the indefinite article appears in Unicode, ʼn.

Table of characters

For more on the pronunciation of the letters below, see Help:IPA/Afrikaans.

| Grapheme | IPA | Examples and Notes |

|---|---|---|

| a | /a/, /ɑː/ | appel ('apple'; /a/), tale ('languages'; /ɑː/). Represents /a/ in closed syllables and /ɑː/ in stressed open syllables |

| á | /a/, /ɑ:/ | ná (after) |

| ä | /a/, /ɑ:/ | sebraägtig ('zebra-like'). The diaeresis indicates the start of new syllable. |

| aa | /ɑː/ | aap ('monkey', 'ape'). Only occurs in closed syllables. |

| aai | /ɑːi/ | draai ('turn') |

| ae | /ɑːə/ | vrae ('questions'); the vowels belong to two separate syllables |

| ai | /ai/ | baie ('many', 'much' or 'very'), ai (expression of frustration or resignation) |

| b | /b/, /p/ | boom ('tree') |

| c | /s/, /k/ | Found only in borrowed words or proper nouns; the former pronunciation occurs before 'e', 'i', or 'y'; featured in the Latinate plural ending -ici (singular form -ikus) |

| ch | /ʃ/, /x/, /k/ | chirurg ('surgeon'; /ʃ/; typically sj is used instead), chemie ('chemistry'; /x/), chitien ('chitin'; /k/). Found only in recent loanwords and in proper nouns |

| d | /d/, /t/ | dag ('day'), deel ('part', 'divide', 'share') |

| dj | /d͡ʒ/, /k/ | djati ('teak'), broodjie ('sandwich'). Used to transcribe foreign words for the former pronunciation, and in the diminutive suffix -djie for the latter in words ending with d |

| e | /e(ː)/, /æ(ː)/, /ɪə/, /ɪ/, /ə/ | bed (/e/), mens ('person', /eː/) (lengthened before /n/) ete ('meal', /ɪə/ and /ə/ respectively), ek ('I', /æ/), berg ('mountain', /æː/) (lengthened before /r/). /ɪ/ is the unstressed allophone of /ɪə/ |

| é | /e(ː)/, /æ(ː)/, /ɪə/ | dié ('this'), mét ('with', emphasised), ék ('I; me', emphasised), wéét ('know', emphasised) |

| è | /e/ | Found in loanwords (like crèche) and proper nouns (like Eugène) where the spelling was maintained, and in four non-loanwords: nè ('yes?', 'right?', 'eh?'), dè ('here, take this!' or '[this is] yours!'), hè ('huh?', 'what?', 'eh?'), and appèl ('(formal) appeal' (noun)). |

| ê | /eː/, /æː/ | sê ('to say'), wêreld ('world'), lêer ('file') (Allophonically /æː/ before /(ə)r/) |

| ë | - | Diaeresis indicates the start of new syllable, thus ë, ëe and ëi are pronounced like 'e', 'ee' and 'ei', respectively |

| ee | /ɪə/ | weet ('to know'), een ('one') |

| eeu | /ɪu/ | leeu ('lion'), eeu ('century', 'age') |

| ei | /ei/ | lei ('to lead') |

| eu | /ɪɵ/ | seun ('son' or 'lad') |

| f | /f/ | fiets ('bicycle') |

| g | /x/, /ɡ/ | /ɡ/ exists as the allophone of /x/ if at the end of a root word preceded by a stressed single vowel + /r/ and suffixed with a schwa, e.g. berg ('mountain') is pronounced as /bæːrx/, and berge is pronounced as /bæːrɡə/ |

| gh | /ɡ/ | gholf ('golf'). Used for /ɡ/ when it is not an allophone of /x/; found only in borrowed words. If the h instead begins the next syllable, the two letters are pronounced separately. |

| h | /ɦ/ | hael ('hail'), hond ('dog') |

| i | /i/, /ə/ | kind ('child'; /ə/), ink ('ink'; /ə/), krisis ('crisis'; /i/ and /ə/ respectively), elektrisiteit ('electricity'; /i/ for all three; third 'i' is part of diphthong 'ei') |

| í | /i/, /ə/ | krísis ('crisis', emphasised), dít ('that', emphasised) |

| î | /əː/ | wîe (plural of wig; 'wedges' or 'quoins') |

| ï | /i/, /ə/ | Found in words such as beïnvloed ('to influence'). The diaeresis indicates the start of new syllable. |

| ie | /i(ː)/ | iets ('something'), vier ('four') |

| j | /j/ | julle (plural 'you') |

| k | /k/ | kat ('cat'), kan ('can' (verb) or 'jug') |

| l | /l/ | lag ('laugh') |

| m | /m/ | man ('man') |

| n | /n/ | nael ('nail') |

| ʼn | /ə/ | indefinite article ʼn ('a'), styled as a ligature (Unicode character U+0149) |

| ng | /ŋ/ | sing ('to sing') |

| o | /o/, /ʊə/, /ʊ/ | op ('up(on)'; /o/), grote ('size'; /ʊə/), polisie ('police'; /ʊ/) |

| ó | /o/, /ʊə/ | óp ('done, finished', emphasised), gróót ('huge', emphasised) |

| ô | /oː/ | môre ('tomorrow') |

| ö | /o/, /ʊə/ | Found in words such as koöperasie ('co-operation'). The diaeresis indicates the start of new syllable, thus ö is pronounced the same as 'o' based on the following remainder of the word. |

| oe | /u(ː)/ | boek ('book'), koers ('course', 'direction') |

| oei | /ui/ | koei ('cow') |

| oo | /ʊə/ | oom ('uncle' or 'sir') |

| ooi | /oːi/ | mooi ('pretty', 'beautiful'), nooi ('invite') |

| ou | /ɵu/ | By itself means ('guy'). Sometimes spelled ouw in loanwords and surnames, for example Louw. |

| p | /p/ | pot ('pot'), pers ('purple' — or 'press' indicating the news media; the latter is often spelled with an <ê>) |

| q | /k/ | Found only in foreign words with original spelling maintained; typically k is used instead |

| r | /r/ | rooi ('red') |

| s | /s/, /z/, /ʃ/, /ʒ/ | ses ('six'), stem ('voice' or 'vote'), posisie ('position', /z/ for first 's', /s/ for second 's'), rasioneel ('rational', /ʃ/ (nonstandard; formally /s/ is used instead) visuëel ('visual', /ʒ/ (nonstandard; /z/ is more formal) |

| sj | /ʃ/ | sjaal ('shawl'), sjokolade ('chocolate') |

| t | /t/ | tafel ('table') |

| tj | /tʃ/, /k/ | tjank ('whine like a dog' or 'to cry incessantly'). The latter pronunciation occurs in the common diminutive suffix "-(e)tjie" |

| u | /ɵ/, /y(ː)/ | stuk ('piece'), unie ('union'), muur ('wall') |

| ú | /œ/, /y(:)/ | búk ('bend over', emphasised), ú ('you', formal, emphasised) |

| û | /ɵː/ | brûe ('bridges') |

| ü | - | Found in words such as reünie ('reunion'). The diaeresis indicates the start of a new syllable, thus ü is pronounced the same as u, except when found in proper nouns and surnames from German, like Müller. |

| ui | /ɵi/ | uit ('out') |

| uu | /y(ː)/ | uur ('hour') |

| v | /f/, /v/ | vis ('fish'), visuëel ('visual') |

| w | /v/, /w/ | water ('water'; /v/); allophonically /w/ after obstruents within a root; an example: kwas ('brush'; /w/) |

| x | /z/, /ks/ | xifoïed ('xiphoid'; /z/), x-straal ('x-ray'; /ks/). |

| y | /əi/ | byt ('bite') |

| ý | /əi/ | hý ('he', emphasised) |

| z | /z/ | Zoeloe ('Zulu'). Found only in onomatopoeia and loanwords |

Afrikaans phrases

Although there are many different dialects and accents, the transcription would be fairly standard.

| Afrikaans | IPA | Dutch | IPA | English | German |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hallo! Hoe gaan dit? | [ɦaləu ɦu χɑːn dət] | Hallo! Hoe gaat het (met jou/je/u)? Also used: Hallo! Hoe is het? |

[ɦɑloː ɦu ɣaːt ɦət] | Hello! How goes it? (Hello! How are you?) | Hallo! Wie geht's? (Hallo! Wie geht's dir/Ihnen?) |

| Baie goed, dankie. | [baiə χut daŋki] | Heel goed, dank je. | [ɦeːl ɣut dɑŋk jə] | Very well, thank you. | Sehr gut, danke. |

| Praat jy Afrikaans? | [prɑːt jəi afrikɑːns] | Spreek/Praat jij/je Afrikaans? | [spreːk/praːt jɛi̯/jə ɑfrikaːns] | Do you speak Afrikaans? | Sprichst du Afrikaans? |

| Praat jy Engels? | [prɑːt jəi ɛŋəls] | Spreek/Praat jij/je Engels? | [spreːk/praːt jɛi̯/jə ɛŋəls] | Do you speak English? | Sprichst du Englisch? |

| Ja. | [jɑː] | Ja. | [jaː] | Yes. | Ja. |

| Nee. | [nɪə] | Nee. | [neː] | No. | Nein. Also: Nee. (Colloquial) |

| 'n Bietjie. | [ə biki] | Een beetje. | [ə beːtjə] | A bit. | Ein bisschen. Sometimes shortened in text: "'n bisschen" |

| Wat is jou naam? | [vat əs jœu nɑːm] | Hoe heet jij/je? / Wat is jouw naam? | [ʋɑt ɪs jɑu̯ naːm] | What is your name? | Wie heißt du? / Wie ist dein Name? |

| Die kinders praat Afrikaans. | [di kən(d̚)ərs prɑːt ˌafriˈkɑːns] | De kinderen spreken Afrikaans. | [də kɪndərən spreːkən ɑfrikaːns] | The children speak Afrikaans. | Die Kinder sprechen Afrikaans. |

| Ek is lief vir jou. Less common: Ek het jou lief. |

[æk əs lif fər jɵu] | Ik hou van jou/je. Common in Southern Dutch: Ik heb je/jou/u lief. |

[ɪk ɦɑu̯ vɑn jɑu̯/jə], [ɪk ɦɛb jə/jɑu̯/y lif] | I love you. | Ich liebe dich. Also: Ich habe dich lieb. (Colloquial; virtually no romantic connotation) |

In the Dutch language the word Afrikaans means African, in the general sense. Consequently, Afrikaans is commonly denoted as Zuid-Afrikaans. This ambiguity also exists in Afrikaans itself and is resolved either in the context of its usage, or by using Afrika- in the adjective sense (e.g. Afrika-olifant for African elephant).

A handful of Afrikaans words are exactly the same as in English. The following Afrikaans sentences, for example, are exactly the same in the two languages, in terms of both their meaning and spelling; only their pronunciation differs.

- My pen was in my hand. ([məi pɛn vas ən məi ɦant])[128]

- My hand is in warm water. ([məi ɦant əs ən varm vɑːtər])

Sample text

Psalm 23 1983 translation:[129]

Die Here is my Herder, ek kom niks kort nie.

Hy laat my rus in groen weivelde. Hy bring my by waters waar daar vrede is.

Hy gee my nuwe krag. Hy lei my op die regte paaie tot eer van Sy naam.

Selfs al gaan ek deur donker dieptes, sal ek nie bang wees nie, want U is by my. In U hande is ek veilig.

Psalm 23 1953 translation:[130]

Die Here is my Herder, niks sal my ontbreek nie.

Hy laat my neerlê in groen weivelde; na waters waar rus is, lei Hy my heen.

Hy verkwik my siel; Hy lei my in die spore van geregtigheid, om sy Naam ontwil.

Al gaan ek ook in 'n dal van doodskaduwee, ek sal geen onheil vrees nie; want U is met my: u stok en u staf die vertroos my.

Lord's Prayer (Afrikaans New Living translation)

Ons Vader in die hemel, laat U Naam geheilig word.

Laat U koningsheerskappy spoedig kom.

Laat U wil hier op aarde uitgevoer word soos in die hemel.

Gee ons die porsie brood wat ons vir vandag nodig het.

En vergeef ons ons sondeskuld soos ons ook óns skuldenaars vergewe het.

Bewaar ons sodat ons nie aan verleiding sal toegee nie; en bevry ons van die greep van die bose.

Want van U is die koninkryk,

en die krag,

en die heerlikheid,

tot in ewigheid.

Amen

Lord's Prayer (Original translation):

Onse Vader wat in die hemel is,

laat U Naam geheilig word;

laat U koninkryk kom;

laat U wil geskied op die aarde,

net soos in die hemel.

Gee ons vandag ons daaglikse brood;

en vergeef ons ons skulde

soos ons ons skuldenaars vergewe

en laat ons nie in die versoeking nie

maar verlos ons van die bose

Want aan U behoort die koninkryk

en die krag

en die heerlikheid

tot in ewigheid.

Amen

See also

- Aardklop Arts Festival

- Afrikaans literature

- Afrikaans speaking population in South Africa

- Arabic Afrikaans

- Handwoordeboek van die Afrikaanse Taal (Afrikaans Dictionary)

- Differences between Afrikaans and Dutch

- IPA/Afrikaans

- Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees (Arts Festival)

- Languages of South Africa

- Languages of Zimbabwe § Afrikaans

- List of Afrikaans language poets

- List of Afrikaans singers

- List of English words of Afrikaans origin

- South African Translators' Institute

- Tsotsitaal

Notes

- ↑ What follows are estimations. Afrikaans has 16.3 million speakers; see de Swaan 2001, p. 216. Afrikaans has a total of 16 million speakers; see Machan 2009, p. 174. About 9 million people speak Afrikaans as a second or third language; see Alant 2004, p. 45, Proost 2006, p. 402. Afrikaans has over 5 million native speakers and 15 million second-language speakers; see Réguer 2004, p. 20. Afrikaans has about 6 million native and 16 million second-language speakers; see Domínguez & López 1995, p. 340. In South Africa, over 23 million people speak Afrikaans, of which a third are first-language speakers; see Page & Sonnenburg 2003, p. 7. L2 "Black Afrikaans" is spoken, with different degrees of fluency, by an estimated 15 million; see Stell 2008–2011, p. 1.

- ↑ Afrikaans borrowed from other languages such as Portuguese, German, Malay, Bantu and Khoisan languages; see Sebba 1997, p. 160, Niesler, Louw & Roux 2005, p. 459.

90 to 95% of Afrikaans vocabulary is ultimately of Dutch origin; see Mesthrie 1995, p. 214, Mesthrie 2002, p. 205, Kamwangamalu 2004, p. 203, Berdichevsky 2004, p. 131, Brachin & Vincent 1985, p. 132. - ↑ It has the widest geographical and racial distribution of all the official languages of South Africa; see Webb 2003, pp. 7, 8, Berdichevsky 2004, p. 131. It has by far the largest geographical distribution; see Alant 2004, p. 45.

It is widely spoken and understood as a second or third language; see Deumert & Vandenbussche 2003, p. 16, Kamwangamalu 2004, p. 207, Myers-Scotton 2006, p. 389, Simpson 2008, p. 324, Palmer 2001, p. 141, Webb 2002, p. 74, Herriman & Burnaby 1996, p. 18, Page & Sonnenburg 2003, p. 7, Brook Napier 2007, pp. 69, 71.

An estimated 40% have at least a basic level of communication; see Webb 2003, p. 7 McLean & McCormick 1996, p. 333. - ↑ kan would be best used in this case because kan nie means cannot and since he is sick he is unable to come, whereas sal is "will" in English and is thus not the best word choice.

References

Citations

- 1 2 Afrikaans at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- ↑ Webb (2002), 14:78.

- ↑ Aarons & Reynolds, "South African Sign Language" in Monaghan (ed.), Many Ways to be Deaf: International Variation in Deaf Communities (2003).

- ↑ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ↑ Roach, Peter (2011). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15253-2.

- ↑ Pithouse, K.; Mitchell, C; Moletsane, R. Making Connections: Self-Study & Social Action. p. 91.

- ↑ Heese, J. A. (1971). Die herkoms van die Afrikaner, 1657–1867 [The origin of the Afrikaner] (in Afrikaans). Cape Town: A. A. Balkema. OCLC 1821706. OL 5361614M.

- ↑ Kloeke, G. G. (1950). Herkomst en groei van het Afrikaans [Origin and growth of Afrikaans] (PDF) (in Dutch). Leiden: Universitaire Pers Leiden. Archived from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ↑ Heeringa, Wilbert; de Wet, Febe; van Huyssteen, Gerhard B. (2015). "The origin of Afrikaans pronunciation: a comparison to west Germanic languages and Dutch dialects". Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics Plus. 47. doi:10.5842/47-0-649. ISSN 2224-3380.

- ↑ Coetzee, Abel (1948). Standaard-Afrikaans [Standard Afrikaans] (PDF). Johannesburg: Pers van die Universiteit van die Witwatersrand. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ↑ Deumert, Ana (12 July 2017). "Creole as necessity? Creole as choice?". Language Contact in Africa and the African Diaspora in the Americas. Creole Language Library. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. 53: 101–122. doi:10.1075/cll.53.05due. ISBN 978-90-272-5277-7. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ↑ Smith, J.J (1952). "Theories About the Origin of Afrikaans" (PDF). Hofmeyer Foundation Lectures, University of the Witwatersrand. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ↑ Afrikaans was historically called Cape Dutch; see Deumert & Vandenbussche 2003, p. 16, Conradie 2005, p. 208, Sebba 1997, p. 160, Langer & Davies 2005, p. 144, Deumert 2002, p. 3, Berdichevsky 2004, p. 130.

Afrikaans is rooted in seventeenth century dialects of Dutch; see Holm 1989, p. 338, Geerts & Clyne 1992, p. 71, Mesthrie 1995, p. 214, Niesler, Louw & Roux 2005, p. 459.

Afrikaans is variously described as a creole, a partially creolised language, or a deviant variety of Dutch; see Sebba 2007, p. 116. - ↑ For morphology; see Holm 1989, p. 338, Geerts & Clyne 1992, p. 72. For grammar and spelling; see Sebba 1997, p. 161.

- ↑ Dutch and Afrikaans share mutual intelligibility; see Gooskens 2007, p. 453, Holm 1989, p. 338, Baker & Prys Jones 1997, p. 302, Egil Breivik & Håkon Jahr 1987, p. 232.

For written mutual intelligibility; see Sebba 2007, Sebba 1997, p. 161. - 1 2 Census 2011: Census in brief (PDF). Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. 2012. p. 27. ISBN 9780621413885. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2015.

- ↑ "Community profiles > Census 2011". Statistics South Africa Superweb. Archived from the original on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ The changed spelling rule was introduced in article 1, rule 3, of the Dutch "orthography law" of 14 February 1947. In 1954 the Word list of the Dutch language which regulates the spelling of individual words including the word Afrikaans was first published.Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties (21 February 1997). "Wet voorschriften schrijfwijze Nederlandsche taal". wetten.overheid.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ↑ "Afrikaans". Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 "Afrikaans". Omniglot. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ↑ "Afrikaans language". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 31 August 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ↑ Alatis; Hamilton; Tan, Ai-Hui (2002). Georgetown University Round Table on Languages and Linguistics 2000: Linguistics, Language and the Professions: Education, Journalism, Law, Medicine, and Technology. Washington, DC: University Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-87840-373-8.

- ↑ Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah, eds. (2008). Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Oxford: Elsevier. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7.

- ↑ den Besten, Hans (1989). "From Khoekhoe foreignertalk via Hottentot Dutch to Afrikaans: the creation of a novel grammar". In Pütz; Dirven (eds.). Wheels within wheels: papers of the Duisburg symposium on pidgin and creole languages. Frankfurt-am-Main: Peter Lang. pp. 207–250.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forke, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2020). "Hottentot Dutch". Glottolog 4.3.

- ↑ Kaplan, Irving (1971). Area Handbook for the Republic of South Africa (PDF). pp. 46–771.

- ↑ James Louis Garvin, ed. (1933). "Cape Colony". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Clark, Nancy L.; William H. Worger (2016). South Africa: The Rise and Fall of Apartheid (3rd ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-12444-8. OCLC 883649263.

- ↑ Worden, Nigel (2010). Slavery in Dutch South Africa. Cambridge University Press. pp. 40–43. ISBN 978-0521152662.

- ↑ Thomason & Kaufman (1988), pp. 252–254.

- ↑ Thomason & Kaufman (1988), p. 256.

- ↑ "Afrikaans Language Courses in London". Keylanguages.com. Archived from the original on 12 August 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- 1 2 Kaplan, R. B.; Baldauf, R. B. "Language Planning & Policy: Language Planning and Policy in Africa: Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique and South Africa". Retrieved 17 March 2017. (registration required)

- ↑ "Afrikaans becomes the official language of the Union of South Africa". South African History Online. 16 March 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ↑ "Speech by the Minister of Art and Culture, N Botha, at the 30th anniversary festival of the Afrikaans Language Monument" (in Afrikaans). South African Department of Arts and Culture. 10 October 2005. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ↑ Galasko, C. (November 2008). "The Afrikaans Language Monument". Spine. 33 (23). doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000339413.49211.e6.

- 1 2 Tomasz, Kamusella; Finex, Ndhlovu (2018). The Social and Political History of Southern Africa's Languages. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-1-137-01592-1.

- ↑ "Afrikaner". South African History Online. South African History Online (SAHO). Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ↑ Bogaards, Attie H. "Bybelstudies" (in Afrikaans). Archived from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- ↑ "Afrikaanse Bybel vier 75 jaar" (in Afrikaans). Bybelgenootskap van Suid-Afrika. 25 August 2008. Archived from the original on 9 June 2008. Retrieved 23 September 2008.

- ↑ "Bible Society of South Africa - Afrikaans Bible translation". www.bybelgenootskap.co.za. Archived from the original on 25 July 2020. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ↑ Harbert, Wayne (2007). The Germanic Languages. Cambridge University Press. pp. 17. ISBN 978-0-521-80825-5.

- ↑ "Afrikaans is making a comeback in Argentina - along with koeksisters and milktart". Business Insider South Africa. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "ABS: Language used at Home by State and Territory". ABS. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ↑ "Census Profile, 2016 Census of Canada". 8 February 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ↑ "2011 Census: Detailed analysis - English language proficiency in parts of the United Kingdom, Main language and general health characteristics". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ↑ "Language according to age and sex by region, 1990-2021". Statistics Finland. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ↑ "Press Statement Census 2016 Results Profile 7 - Migration and Diversity - CSO - Central Statistics Office". www.cso.ie.

- ↑ "Top 25 Languages in New Zealand | Ministry for Ethnic Communities". www.ethniccommunities.govt.nz.

- ↑ "2016 American Community Survey, 5-year estimates". Ipums USA. University of Minnesota. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ↑ Wessel Visser (3 February 2005). "Die dilemma van 'n gedeelde Afrikaanse identiteit: Kan wit en bruin mekaar vind?" [The dilemma of a shared African identity: Can white and brown find each other?] (in Afrikaans). Archived from the original on 22 December 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ↑ Frydman, Jenna (2011). "A Critical Analysis of Namibia's English-only language policy". In Bokamba, Eyamba G. (ed.). Selected proceedings of the 40th Annual Conference on African Linguistics – African languages and linguistics today (PDF). Somerville, Massachusetts: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. pp. 178–189. ISBN 978-1-57473-446-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ↑ Willemyns, Roland (2013). Dutch: Biography of a Language. Oxford University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-19-985871-2.

- ↑ "Armoria patriæ – Republic of Bophuthatswana". Archived from the original on 26 October 2009.

- ↑ Kamau, John (25 December 2020). "Eldoret, the town that South African Boers started". Business Daily.

- ↑ Govt info available online in all official languages – South Africa – The Good News Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Black Linguistics: Language, Society and Politics in Africa and the Americas, by Sinfree Makoni, p. 120S.

- 1 2 Lafon, Michel (2008). "Asikhulume! African Languages for all: a powerful strategy for spearheading transformation and improvement of the South African education system". In Lafon, Michel; Webb, Vic; Wa Kabwe Segatti, Aurelia (eds.). The Standardisation of African Languages: Language political realities. Institut Français d'Afrique du Sud Johannesburg. p. 47. Retrieved 30 January 2021 – via HAL-SHS.

- ↑ Lynsey Chutel (25 February 2016). "South Africa: Protesting students torch university buildings". Stamford Advocate. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ↑ "Studentenunruhen: Konflikte zwischen Schwarz und Weiß" [Student unrest: conflicts between black and white]. Die Presse. 25 February 2016.

- ↑ "Südafrika: "Unerklärliche" Gewaltserie an Universitäten" [South Africa: "Unexplained" violence at universities]. Euronews. 25 February 2016. Archived from the original on 27 February 2016. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ↑ Constitution of the Western Cape, 1997, Chapter 1, section 5(1)(a)

- ↑ "Superbrands.com, visited on 21 March 2012" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015.

- ↑ Pressly, Donwald (5 December 2005). "Rupert snubs mag over Afrikaans slur". Business Africa. Archived from the original on 16 February 2006. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ↑ Afrikaans stars join row over 'ugly language' Archived 27 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine Cape Argus, 10 December 2005.

- ↑ Mesthrie 1995, p. 214.

- ↑ Brachin & Vincent 1985, p. 132.

- ↑ Mesthrie 2002, p. 205.

- ↑ Sebba 1997, p. 161

- 1 2 Holm 1989, p. 338

- 1 2 Sebba 1997

- ↑ Baker & Prys Jones 1997, p. 302

- ↑ Egil Breivik & Håkon Jahr 1987, p. 232

- ↑ Sebba 2007

- 1 2 3 4 Gooskens 2007, pp. 445–467

- ↑ Language Standardization and Language Change: The Dynamics of Cape Dutch. John Benjamins Publishing Company. 2004. p. 22. ISBN 9027218579. Retrieved 10 November 2008.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Niesler, Louw & Roux 2005, pp. 459–474

- ↑ "Afrikaans: Standard Afrikaans". Lycos Retriever. Archived from the original on 20 November 2011.

- ↑ ten Thije, Jan D.; Zeevaert, Ludger (2007). Receptive Multilingualism: Linguistic analyses, language policies and didactic concepts. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 17. ISBN 978-9027219268. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ↑ S. Linfield, interview in Salmagundi; 2000.

- 1 2 3 4 "Languages — Afrikaans". World Data Atlas. Archived from the original on 4 October 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2014.

- ↑ "2.8 Home language by province (percentages)". Statistics South Africa. Archived from the original on 24 August 2007. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ↑ "Table 2.6: Home language within provinces (percentages)" (PDF). Census 2001 - Census in brief. Statistics South Africa. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2005. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

- ↑ Oranje FM, Radio Sonder Grense, Jacaranda FM, Radio Pretoria, Rapport, Beeld, Die Burger, Die Son, Afrikaans news is run everyday; the PRAAG website is a web-based news service. On pay channels, it is provided as second language on all sports, Kyknet

- ↑ "Hannes van Zyl". Oulitnet.co.za. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- 1 2 Pienaar, Antoinette; Otto, Hanti (30 October 2012). "Afrikaans groei, sê sensus (Afrikaans growing according to census)". Beeld. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ↑ Prince, Llewellyn (23 March 2013). "Afrikaans se môre is bruin (Afrikaans' tomorrow is coloured)". Rapport. Archived from the original on 31 March 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2013.

- ↑ "Platteland Film". www.plattelanddiemovie.com.

- ↑ SABC3 "tests" Afrikaans programming Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Screen Africa, 15 April 2009

- ↑ "Namibia 2011 Population & Housing Census Main Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 October 2013.

- ↑ "Afrikaans vs Zulu row brewing at schools | IOL News". www.iol.co.za.

- ↑

- ↑ Donaldson (1993), pp. 2–7.

- ↑ Wissing (2016).

- ↑ Donaldson (1993:4–6)

- ↑ Donaldson (1993), pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Donaldson (1993:4, 6–7)

- ↑ Swanepoel (1927:38)

- ↑ Donaldson (1993:7)

- ↑ Donaldson (1993:3, 7)

- ↑ Donaldson (1993:2, 8–10)

- ↑ Lass (1987:117–119)

- ↑ Donaldson (1993:10)

- ↑ Donaldson (1993), pp. 13–15.

- ↑ Donaldson (1993), pp. 13–14, 20–22.

- ↑ Den Besten (2012)

- 1 2 "John Wells's phonetic blog: velar or uvular?". 5 December 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2015. Only this source mentions the trilled realization.

- ↑ Bowerman (2004:939)

- ↑ Lass (1987), p. 117.

- ↑ Donaldson (1993), p. 15.

- ↑ They were named before the establishment of the current Western Cape, Eastern Cape, and Northern Cape provinces, and are not dialects of those provinces per se.

- 1 2 "Afrikaans 101". Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ↑ "Lekker Stories". Kaapse Son - Die eerste Afrikaanse Poniekoerant (in Afrikaans). Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ↑ Szpiech, Ryan; W. Coetzee, Andries; García-Amaya, Lorenzo; Henriksen, Nicholas; L. Alberto, Paulina; Langland, Victoria (14 January 2019). "An almost-extinct Afrikaans dialect is making an unlikely comeback in Argentina". Quartz.

- 1 2 "Afrikaans history and development. The Unique Language of South Africa". Safariafrica.co.za. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ↑ "Sambreel - (Zonnescherm)". Etymologiebank.nl. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- 1 2 Austin, Peter, ed. (2008). One Thousand Languages: Living, Endangered, and Lost. University of California Press. p. 97. ISBN 9780520255609.

- ↑ "ASSAGAAI". gtb.inl.nl. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ↑ "Karos II : Kros". Gtb.inl.nl. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ↑ Potgieter, D. J., ed. (1970). "Afrikaans". Standard Encyclopaedia of Southern Africa. Vol. 1. NASOU. p. 111. ISBN 9780625003280.

- ↑ Döhne, J. L. (1857). A Zulu-Kafir Dictionary, Etymologically Explained... Preceded by an Introduction on the Zulu-Kafir Language. Cape Town: Printed at G.J. Pike's Machine Printing Office. p. 87.

- ↑ Samuel Doggie Ngcongwane (1985). The Languages We Speak. University of Zululand. p. 51. ISBN 9780907995494.

- ↑ David Johnson; Sally Johnson (2002). Gardening with Indigenous Trees. Struik. p. 92. ISBN 9781868727759.

- ↑ Strohbach, Ben J.; Walters, H.J.A. (Wally) (November 2015). "An overview of grass species used for thatching in the Zambezi, Kavango East and Kavango West Regions, Namibia". Dinteria. Windhoek, Namibia (35): 13–42.

- ↑ South African Journal of Ethnology. Vol. 22–24. Bureau for Scientific Publications of the Foundation for Education, Science and Technology. 1999. p. 157.

- ↑ Toward Freedom. Vol. 45–46. 1996. p. 47.

- ↑ "Retrieved 12 April 2010". 101languages.net. 26 August 2007. Archived from the original on 15 October 2010. Retrieved 22 September 2010.

- ↑ de Bruin, George; Cornelius, Eleanor (1 June 2019), "'My Pen Is in My Hand": 'n Ondersoek na die leksikale aktivering in Engels-Afrikaanse algemene tweetaliges, beroepsvertalers en beroepstolke ('My Pen Is in My Hand": An Investigation of Lexical Activation in English-Afrikaans General Bilinguals, Professional Translators and Professional Interpreters)", Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe (in English and Afrikaans), 59 (2): 216–234, doi:10.17159/2224-7912/2019/v59n2a4, S2CID 202286032

- ↑ "Soek / Vergelyk". Bybelgenootskap van Suid Afrika. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ↑ "Soek / Vergelyk". Bybelgenootskap van Suid Afrika. Archived from the original on 11 May 2020. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

Sources

- Adegbija, Efurosibina E. (1994), "Language Attitudes in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Sociolinguistic Overview", Multilingual Matters, ISBN 9781853592393, retrieved 10 November 2008

- Alant, Jaco (2004), Parlons Afrikaans (in French), Éditions L'Harmattan, ISBN 9782747576369, retrieved 3 June 2010

- Baker, Colin; Prys Jones, Sylvia (1997), Encyclopedia of bilingualism and bilingual education, Multilingual Matters Ltd., ISBN 9781853593628, retrieved 19 May 2010

- Berdichevsky, Norman (2004), Nations, language, and citizenship, Norman Berdichevsky, ISBN 9780786427000, retrieved 31 May 2010

- Batibo, Herman (2005), "Language decline and death in Africa: causes, consequences, and challenges", Oxford Linguistics, Multilingual Matters Ltd, ISBN 9781853598081, retrieved 24 May 2010

- Booij, Geert (1999), "The Phonology of Dutch.", Oxford Linguistics, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-823869-X, retrieved 24 May 2010

- Booij, Geert (2003), "Constructional idioms and periphrasis: the progressive construction in Dutch." (PDF), Paradigms and Periphrasis, University of Kentucky, archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2011, retrieved 19 May 2010

- Bowerman, Sean (2004), "White South African English: phonology", in Schneider, Edgar W.; Burridge, Kate; Kortmann, Bernd; Mesthrie, Rajend; Upton, Clive (eds.), A handbook of varieties of English, vol. 1: Phonology, Mouton de Gruyter, pp. 931–942, ISBN 3-11-017532-0

- Brachin, Pierre; Vincent, Paul (1985), The Dutch Language: A Survey, Brill Archive, ISBN 9004075933, retrieved 3 November 2008