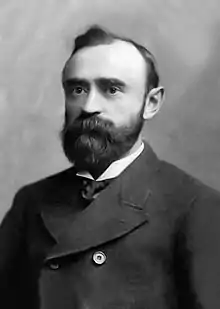

Alexander De Soto | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 28, 1840[1] |

| Died | November 11, 1936 (aged 96) |

| Burial place | Mount Olivet Cemetery, Seattle, Washington, U.S.[14] |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1890–1936 |

| Organizations | |

| Known for | Established the first Seattle's public hospital; co-founded and managed the De Soto Placer Mining Company, the biggest mining company of its time; first businessman to introduce dredge mining to Alaska. |

| Political party | Republican[23] |

| Relatives | Hernando De Soto[5] |

Alexander De Soto (July 28, 1840 – November 11, 1936) was a Spanish-American physician, philanthropist, and businessman. He is best known for establishing Seattle's first hospital, the Wayside Mission Hospital, which he directed from 1898 to 1904. A born again Protestant, De Soto wanted to help more poor, homeless, sick, and people with addiction, and wanted to create a business that would finance his numerous philanthropic plans. At the zenith of his business career, De Soto was involved in mining businesses in Chile, Peru, Spain, North and South America, South Africa, and Mexico. He co-founded the De Soto Placer Mining company which conducted more mining activity than any other company of the time in Snohomish County, Washington, and was the first businessman to introduce dredge mining to Alaska. The company-owned Alaskan lands were considered the richest and best-equipped in the world, featuring the largest dredges and steam shovels available in 1903.

De Soto was born in the western Pacific Ocean's Caroline Islands, and educated in Spain. He arrived to America in 1862, and served as a navy surgeon in Federal Navy during the American Civil War. In 1867, he worked as surgeon in Alaska. He was one of the leaders of the Carlist movement. From 1870 to 1872, De Soto lived in Sweden, where he served as physician for King Charles XV. Later, he moved his practice to Chile and Peru. In 1879 and 1880, he served as an army surgeon for Chile in the War of the Pacific. De Soto's life took a turn when he developed an interest in gambling, which led to a morphine addiction. He was saved and converted to Protestantism, becoming a member of the New York Crittenton and the Bleecker Street Missions, and later of the Bowery Mission. In 1879, De Soto led a gospel expedition to Alaska, which failed to reach Klondike ending instead in Seattle, Washington, where De Soto established the city's first hospital and continued his missionary and philanthropic work.

De Soto started other business ventures to finance his missionary projects. He was involved in planning a railroad to Alaska as well as his mining business. Only his mining business was initially successful, as the Granite Falls mine in Snohomish County turned a profit. De Soto's decision to reinvest the proceedings into a gargantuan project in Alaska, although initially very promising, proved mistaken. De Soto successfully secured a significant investment fund and delivered state-of-the-art dredging equipment to Alaska, but the business idea failed, as his mining company's land didn't yield enough gold. De Soto was accused of mismanagement, and after several more unsuccessful attempts, he abandoned the mining business and returned to medicine. In 1910, he unsuccessfully ran for King County Coroner, and then went to Sweden, where he served as physician and dietician for the King of Norway from 1910 to 1915. Later, he returned to New York. In 1936, at the age of 95, as he was working as a dietician on the private yacht Centaur, he died soon after falling into the Gowanus Bay in Brooklyn.

In the 1920s, an historical plaque and an anchor marker were installed on the Washington Street Public Boat Landing in Seattle to commemorate De Soto and the Wayside Mission and Hospital.

Early life and family

De Soto was born on July 28, 1840,[1][8][9] in the Caroline Islands, a Spanish colony at the time.[note 1] His parents were Fernando De Soto, born in 1791 on the De Soto estate near Barcelona, and Hedwig Leonora De Soto from Austria (she died in 1862).[1] Alexander's father was a general in Spain military forces,[6][7] and at one point, the Spanish minister of war.[11] He served as governor of the Caroline Islands, then the lieutenant governor of Puerto Rico, and later as a diplomat until his retirement at 80.[1] Fernando De Soto died at 111 years old.[24]

According to the family's oral history, Alexander De Soto was a great-great-grandson of Hernando de Soto, the famous Spanish explorer who discovered the Mississippi River.[22][21][25][26][11][24][13][5] As of 1906, De Soto was one of five living descendants of Hernando, including his brother who was a Catholic bishop in Rome; a sister, who lived in Spain; and two cousins.[5]

Education

De Soto spent his early years of education in Sant Quintí de Mediona near Barcelona at a Jesuit college.[4][2][11]

He went on to become a surgeon and physician.[6][7] He received a Doctor of Medicine degree from the University of Spain in Madrid, and proceeded to study in Heidelberg, Germany, where he received a Legum Doctor degree. In 1870, he studied in Uppsala, Sweden.[1]

Career

Early military, civic, and medical career (1862–1880)

In 1862, 22-year old De Soto came to America to study American naval tactics as a Spanish legation (diplomat). He served as a navy surgeon in the U.S. Navy during the American Civil War.[1][22][11][5] In 1867, De Soto worked as a surgeon in Alaska.[27] In 1868, he went back to Spain and became one of the activists of the Carlist movement. He stayed in Spain until the early 1870s, when he left to study and work in Sweden.[1][22][21][25]

From 1870 to 1872, De Soto worked as a surgeon and professor in Uppsala, Sweden, and served as physician for King Charles XV (who reigned from 1859 to 1872). Between 1872 and 1875, De Soto moved his medical practice to Chili and Peru. In 1879 and 1880, he served as a Chilean army surgeon in the War of the Pacific, a dispute between Chile and a Bolivian-Peruvian alliance.[1][13][11][22][21][25]

In the late 1870s, De Soto developed an interest in card games and gambling, and briefly worked as croupier in Berlin, Germany.[28] In 1880, De Soto went to London; from there he returned to America, settling in New York.[1]

Gambling and addiction (1880–1890)

De Soto continued to gamble while settling in New York in 1880.[3][1][29] He also developed a morphine addiction.[4][30] Later, he moved further west and gambled in Colorado mining camps.[22][21][25]

Missionary and medical career (1890–1936)

In 1890, De Soto experienced religious salvation and converted to Protestantism. He quit gambling and overcame his morphine addiction. The experience prompted him to start active missionary work. He returned to New York State and briefly worked in leather goods manufacturing in Freeport, Long Island.[4][2][25][3][4][22][21]

In New York, he attended the Crittenton and the Bleecker Street Missions. In 1897, he joined the New York Bowery Mission.[4][22][21][25][3]

After engaging in missionary work for several years, he decided to create and lead a gospel expedition to Alaska.[4]

Gospel mission to Alaska (1897–1898)

In November 1897, seven members of the New York Bowery Mission, led by De Soto, started a trip to the Klondike region to bring worship and gospel sessions to Alaskan gold miners and natives. Their main goal was to establish a mission similar to those in New York in Dawson City. They were determined to hold worship meetings at every point on their route from New Jersey to California and Washington, and after going through the Chilkoot Pass to Juneau and Dawson.[22][21][25][31][3][32][33]

The travelers also planned to reach Klondike and search for gold, calculating that the gold, if found, would sponsor their missionary work in Klondike as well as in New York. De Soto also wanted to establish a non-profit hospital in the region.[22][21][25][31][26]

However, the group never reached Klondike. In November 1898, a year after their departure from New York, they reached Seattle. They were thwarted by unfavorable weather conditions and De Soto's injury—he broke his leg and needed time to recover. De Soto learned that there was no public hospital in Seattle, and decided to build one.[26][4][10][33]

Wayside Mission and Hospital (1898–1909)

In 1898, having started a small medical practice in Seattle, De Soto invested much of his own money to establish the Seattle Wayside Mission, of which he became president.[33][34][33][35][26][4][36][37][38] The first Mission meeting took place on November 8, 1898, in a building on the Railroad avenue.[33]

The daily indoor and outdoors mission meetings consisted of songs, prayers, preaching, and testimonies. Every meeting provided free mental and medical support for the needy people of the city, with a focus on drug, alcohol, and gambling addicts. Homeless people were also provided with temporary housing.[33][4]

Seeing how many people returned to Seattle poor, sick, and injured from gold fields after the Klondike Gold Rush, De Soto decided to build the Wayside Mission Hospital. There was no other establishment in Seattle where people could get free medical treatment[1][5][39] until 1909, when the city opened its own public hospital.[40]

De Soto met Captain Amos C. Benjamin and Judge Roger S. Greene as fellow members of the Tabernacle Baptist Church in Seattle. In the spring of 1899, they co-founded the Seattle Benevolent Society in order to lobby for and recruit investors in the establishment of the Wayside Hospital.[6][41][2][42][33] Thanks to De Soto's experience in treating the sick and addicted, he was highly esteemed by the Seattle police department and other influential friends, who convinced the city to assist him in opening the hospital.[43] The Wayside Mission Hospital was established on April 1, 1899, as the first free hospital in the city.[44][45][46] De Soto invested his own money into the establishment as well as recruiting contributions from businesses and citizens.[47] De Soto's good friend, business colleague, and philanthropist John J. Habecker[48][29] became one of the biggest investors of the Wayside Mission Hospital, and helped manage it.[49][50][10][51][52]

In their formative years, the Wayside Mission and Hospital were supported by the Free Methodist, Baptist, and Congregational churches of Seattle. For over a year, the North Baptist Church of Seattle provided the bread for the mission. The Seattle Seminary helped the mission organize meetings.[33][26][35] A number of business companies and well-known people of Seattle helped provide necessary medicines and food.[4] In 1903, English actress Rose Coghlan donated her earnings from three performances of The Second Mrs. Tanqueray in Seattle to the hospital.[53] That same year, it was announced that all profits from De Soto's mining properties in Granite Falls, Washington would be dedicated to charities across Puget Sound including the Wayside Hospital.[48][29] The mission and hospital's primary goal was the treatment of poverty-related illnesses and industrial accidents, treating lumberjacks, sailors, miners, and others.[54][2] De Soto became determined to provide medical assistance of all kinds of starving, sick, and lonely people neglected by the government, many of whom were in hopeless conditions due to difficult illnesses, but mostly due to severe opium and morphine addictions.[33][37][34][26][55][48][36] Soon, treating drug addicts became De Soto's specialty, and it was stated that addicts left the hospital almost cured.[56]

It was widely known that De Soto himself visited the streets, bars, saloons, and other public places to find those who needed rescuing and medical assistance.[26][43] On a number of occasions De Soto dealt with suicidal patients retrieving them from the Seattle harbor.[57][58] The hospital became well known across the Pacific Coast,[2][59] and sheltered poor and sick people from across the Puget Sound region.[60][47]

Floating hospital establishment (1900)

In 1900, it was decided to expand the Wayside Mission Hospital to new territory. The members of the Seattle Benevolent Society bought the steamer Idaho from the Cahn & Cohn company, and renovated it to be a hospital ship. The city provided a spot to dock the vessel at the Jackson Street slip.[61][33][37][34][4][6][41][2][42] De Soto resigned from the Seattle Benevolent Society to be able to lease the boat from them and build his hospital there.[50][59][52]

The Seattle Benevolent Society started fundraising.[61] Immediately after purchase, all the steamer's machinery was ripped out to provide space for wards.[8][9] At first, only a small part of the ship was made into hospital bunks, and several patients housed there for treatment supervised by the mission's volunteers. The plan was to develop two decks for hospital wings divided into men's and women's wards.[37][34][35]

At first, De Soto worked alongside eight staff, but the number of people on the hospital's official staff developed rapidly throughout 1900. By September, there were several doctors, male and female nurses, a matron, night guard, cook, and porter. None of the staff earned an official salary.[62][4][34][26]

By the end of 1900, the hospital boat was full of patients. It provided free meals and could treat up to 50 patients at a time. Doctors treated everything from mild injuries to drug addictions for free. If patients were able to pay for their treatment, De Soto occasionally charged them.[4][56] Sticking to the Wayside Mission principles, worship services and prayer sessions were held at the floating hospital.[52]

In 1901, the Wayside Mission Hospital served 7,400 patients. More than 40,000 free meals were given out; in 1901; that number reached 50,000.[38] De Soto stated that in the first three years, he donated $23,480 ($630,000 in 2021 dollars[note 2]) out of his own pocket.[64]

By November 1901, the steamer Idaho was in a critical condition and in need of overhaul. The City Council gave the Wayside Mission permission to build a gridiron at the foot of Jackson street and put the ship on it.[64] But during a severe storm in January 1902, the Idaho broke from its mooring with patients and staff on board. As it was tossed by the waves, its stern was severely damaged by logs that were anchored nearby. People were evacuated from the ship by the city's fire department, and crews of nearby anchored vessels helped to save the boat from sinking, securing it near the wharf.[65] The ship survived the storm and proceeded to be re-moored at its original position.[60][55][66]

Eventually, a strong beam-structured gridiron was built. The ship was dismantled and then installed on its new stern foundation.[67][39][2][6][68]

Cooperation with authorities

In 1900, Do Soto addressed the Health and Sanitation Committee of Seattle, asking for official authority to treat and assist the city's drug addicts. After the discussion, an ordinance was prepared that gave De Soto police authority to prevent the selling of any medicine, that could be used as a drug without prescriptions, and full responsibility for the welfare of the city addicts.[69]

Thanks to De Soto, that same year other ordinances were passed by the City Council. One ordinance made the selling of the opiates without a prescription a criminal offense; the other allowed the municipal court and city jail to remove convicted addicts to the De Soto's floating hospital, using it as a rehabilitation center. The Council paid 50 cents per day per patient for the addicts' containment. However, a year later, the city finance committee introduced a new ordinance: due to budget shortages, the city could no longer pay De Soto to treat addicts, and they were to be kept in the city jail again.[70][71][38][56] Another article stated that drug addicts were not allowed at the hospital anymore because their treatment had proved impractical; there were multiple easy ways of getting drugs in the city.[60] Nevertheless, through 1901 De Soto kept up his "relentless war" against the Seattle druggists who sold morphine and other opiates to addicts.[72]

As there was no municipal hospital in Seattle until 1909, all the city's sick and injured were sent either to the city jail (which De Soto maintained delayed medical assistance), or to the county hospital, making it overflow with patients.[73][40][52][60] In 1902, to support the city (which at the time didn't have the funding to build its own hospital), minimize the damage done to patients at the city jail, and provide people with timely quality medical help, De Soto proposed to dedicate a ward or several wards in the floating hospital specifically for people found sick or injured on the city streets and in public places. He also suggested making his hospital headquarters for and in charge of the city ambulance.[60][56][74]

The City Council and Committee on Health and Sanitation supported De Soto's initiative and agreed to his suggestions. On July 21, 1902, an ordinance was passed sealing the City Council's agreements with De Soto. The ordinance stated that the city's Board of Health and city Health Officers were to send injured and sick people, as well as emergency cases, to the Wayside Mission Hospital instead of other city or county institutions. The city would pay 75 cents per day for their treatment and accommodations for up to three days. Afterwards, the patients were to be removed to the county hospital if needed. De Soto took all expenses on himself, provided the assistance of experienced doctors of his hospital, and appointed a salaried physician in charge of the new ward.[75][73][47][60][74][76][77]

One part of the initial plan failed to work: as the majority of patients had complex injuries and illnesses, it was impossible to let them go after three days. Since the county hospital was overtaxed, many people were left in the Wayside Mission Hospital for a longer period of time. In December 1902, the ordinance and official agreement between De Soto and the City Council expired, but city authorities continued to send cases to the Wayside Mission Hospital.[73][47]

In early 1903, the Wayside Mission Hospital's bill for treating city patients was reduced by 80% by the auditing committee of the City Council. The Council declined to pay for indigent sick people's treatment, stating the issue fell under the County Commissioner's jurisdiction. The County Commissioner's office also rejected their responsibility for the needy patients.[73][47] In 1903, there were hundreds of impoverished sick people in Seattle, and in discussions between the hospital and the officials, it became clear that neither city nor county entities were willing to take responsibility for them. The hospital's officials resented the whole situation. They suggested the City Council spend a part of the "floating fund" to pay for poor people's treatment, and came up with an ordinance regarding the maintenance of Seattle's indigent sick, hoping the council would pass it.[73]

As the City Council didn't fulfill their agreements with De Soto, the relationship became strained. At the Seattle Chamber of Commerce meeting on March 25, 1903, De Soto and Agnes Heath, his hospital manager, addressed the issue again and accused authorities of neglect towards the city's destitute. Eventually, the Chamber of Commerce referred the question of needy people's treatment and its funding to city and county committees.[47]

In April, a joint meeting of county and city committees was held. De Soto took part in it and stated that his private funds and contributions from other people were not enough to treat the rising flow of patients. De Soto suggested that the city establish proper funding for the hospital and increase payment as 75 cents per a day could not cover treatment, further assistance, and food. A new committee was established to solve the problem of hospital funding, and later a new ordinance was passed as to the partnership between the hospital and the City Council.[78][79][47][68] In 1904, the hospital on board the Idaho steamer was incorporated under the name of Wayside Emergency Hospital.[80]

Push to expand the hospital (1903)

.jpg.webp)

As Seattle didn't have a public hospital for emergency cases,[81][52] the Wayside Mission Hospital on board the Idaho steamship served as the receiving city hospital for several years. By 1903, De Soto came to conclusion that the hospital at Idaho was "inadequate" for the number of people needing free medical assistance.[82][35][52]

To make more room for patients, doctors, and other medical assistance, in May 1903 De Soto announced plans for a new modernized Wayside Mission Hospital: a new brick and stone four-story building to replace the Idaho. The rough drafts included wards for 100 patients, ambulance bay, dining rooms, kitchen, linen rooms, dispensary, X-ray rooms, medical and surgical laboratories, nurses dormitories, lecture rooms for the medical and nurses training schools, an elevator. The cost of the new building with all the equipment was appraised from $80,000 to $100,000 (from $2,000,000 to $3,000,000 in 2021 dollars[note 2]). De Soto invested some of his own money (made from his mining dealings) and persuaded several philanthropists to contribute to the construction.[82][83][81][35][84][85]

In May 1903, an ordinance was introduced by the City Council to allow the Seattle Board of Public Works to lease De Soto a 100-by-120-foot (30 by 37 m) piece of land on Jackson Street (the site of the steamer Idaho Site) for 35 years for the purpose of building the new hospital. The rental price was called "merely nominal" at $1 per year. The hospital would run on the same agreements as the floating hospital had, and upon the end of the lease, the city was free to take over the building and equipment or to give another 35-year lease to De Soto, his heirs, or his assignees.[86][87][81][84][85]

A few days later, it was announced that the piece of land where the floating hospital was situated and which De Soto wanted for the new hospital had already been leased by the city to the Columbia & Puget Sound Railroad Company (also known as the Seattle and Walla Walla Railroad, or the Pacific Coast Railroad Company) without De Soto's knowledge. Another obstacle for De Soto was the question of whether the city could legally lease public streets for private purposes.[88][84][84][87]

Despite the fact that prior to these events the city had constantly leased certain parts of public streets,[88] the City Council eventually declined De Soto's proposal without further discussion, and the ordinance for a property lease on Jackson Street failed.[85][89][90] Although there were other site offers for the new hospital,[84][90] De Soto stood his ground, demanding the site by the ocean because the healing medical properties of salt water provided better conditions for patients.[84][66]

The City Council's activity in regard to the new hospital met with strong public response. As the new hospital was widely supported by citizens, the council's decision was criticized by the community and newspapers.[84][90][91] De Soto himself believed the whole situation was created by the Board of Public Works and City Engineers specifically to get him and his hospital out of its spot on Jackson Street.[88][84]

Nevertheless, the existence of the floating hospital was still in question. On June 6, 1903, at a meeting of the Board of Public Works, the Columbia & Puget Sound Railroad Company demanded that the Board give them the present Idaho site in order to build a railroad line. De Soto was present at the meeting, and offered to move the hospital further out in the bay to provide the necessary space for the railroad and save the hospital at the same time. After heated discussions, the Board gave the representatives of the Wayside Mission Hospital and the Columbia & Puget Sound Railroad Company a week to reach some kind of agreement.[67][66] The boat was left at its original site until 1907, when the Oregon Improvement Company started lobbying to build a railroad there.[59][41][45][92]

King County Medical Society opposition

The King County Medical Society had resisted De Soto and his free treatment for the poor ever since he had arrived in Seattle in 1898.[43] In April 1903, De Soto and several other Seattle doctors engaged in open conflict with the Society. Some doctors even moved their practices elsewhere due to the confrontation. The Society was strongly opposed to the establishment of "general medical charity" and De Soto's methods and ideas regarding medical assistance and mental health support to the indigent and addicted. According to a Seattle Daily Times article in 1903, they expelled a member of the society, Dr. Wyllis Sillman, to counter his wishes to open a free dispensary in Seattle. Supporting his colleague, De Soto called out the Society's actions as "incompetence and malpractice," labeling the organization "no longer useful in a community,"[93][43] and invited Dr. Wyllis Sillman to work with him in the Wayside Mission Hospital.[83][94]

Hospital management overhaul and later activity (1904–1913)

.jpg.webp)

In 1904, while De Soto was attending his mining properties in Alaska and second-in-charge J. J. Habecker left for Philadelphia, the hospital was left in the charge of E. G. Johnson. The King County Medical Society saw an opportunity to finally remove De Soto from his position and either close or take control of the hospital. They influenced the Seattle Benevolent Society—the owners of the hospital—to make Johnson resign and appoint another physician in charge. The Society also persuaded the City Council to cut their payments to the hospital for city emergency cases.[95][79][51][51][50] De Soto's management was deemed unsatisfactory, and his lease of the boat and the hospital was revoked. The lease was later given to Fanny W. Connor, manager of the hospital, and Marion Baxter, one of the Seattle Benevolent Society directors.[59][41][51][52]

In order to support the Wayside Mission Hospital, new management held an entertainment and fundraising event in a Seattle theatre. The event was attended by many doctors, nurses, and musicians: among the guests was Anita Newcomb McGee, a well-known American military doctor.[49] In 1905, Marion Baxter was given charge of the hospital. She helped raise money to pay the hospital debts and find further funding.[96] In 1906, the Wayside Mission Hospital operated under Seattle and King County authorities.[5]

In 1907, the Idaho steamer's roof became leaky. At the same time, the Oregon Improvement Company started lobbying to build a railroad line through the hospital site. Eventually, the hospital was removed to the Sarah B. Yesler building, where the Seattle General Hospital had previously operated. It functioned under the name of Wayside Emergency Hospital until 1909, when Seattle opened its first public hospital. From 1910 to 1913, Wayside Emergency Hospital operated under the management of Katherine Major.[97][2][45][40][92][59][20][98][99][30][96][100] The abandoned hull of the Idaho steamer eventually sank into Elliott Bay.[8]

Other Wayside Mission establishments

In August 1901, De Soto expanded the Wayside Mission, opening a new facility on Washington Street in Seattle. It offered much more space for mental health care than the Idaho and the first mission building had.[62][4][52] From August 1900 to November 1901, around 8,000 people (excluding those who stayed on the hospital ship) were given free shelter in the Mission Hall on Washington Street.[38]

In 1901, the Wayside Mission sanitary farm operated in Granite Falls, Washington, under the management of De Soto and J.J. Habecker. The farm was built as a shelter and recovery center for drug addicts who had previously been treated in the Wayside Mission Hospital in Seattle.[38][101][48]

By 1903, De Soto had developed his mining camps in Council City, Alaska, and outlined plans for a 20-bed hospital there, with a physician, surgeon, and trained nurses to assist miners in the area for free.[102][103][104][105] On June 1, equipment and materials for the new hospital in Alaska was shipped from Seattle.[106][107][16] By August 28, 1903, the Council City hospital was successfully built. It was a 30-by-80-foot (9.1 by 24.4 m) building furnished with modern equipment. De Soto was in charge of the hospital and managed a staff of experienced doctors. De Soto also organized a mission in Council City, which operated successfully for a few years.[105][108][109]

Later medical career

After being ousted from his management of the Wayside Mission Hospital in 1904, De Soto's most notable activity in the medical field was in 1910, when he ran for King County Coroner on the Republican ticket. He lost the race and went to Sweden, where he served as physician and dietician for the King of Norway from 1910 to 1915.[13][23] In 1936, De Soto worked as dietician on the private cruise yacht Centaur during a summer cruise of the Great Lakes.[13]

Historical commemorations

In the 1920s, a plaque commemorating the SS Idaho was installed at the newly built Washington Street Boat Landing pergola, on South Washington Street.[110] During the 1960 National Maritime Week, a historical plaque and an anchor marker were installed on Washington Street Public Boat Landing to honor the Wayside Mission and Hospital, De Soto, and the Idaho. In 2014, the boat landing and plaque were temporarily removed to another pier due to the Elliott Bay seawall restoration work.[92][9][30][8]

In 1974, the SS Idaho was featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not! magazine.[8]

In 1982, a children picture book about a mouse dentist Doctor De Soto was published.[111]

Wayside Mission Hospital was the first public hospital in Seattle history.[44][54] It demonstrated the need for public health institutions and spurred the development of medical care for the indigent of the city and county.[54][6][41]

Mining business (1872–1906)

Between 1872 and 1875, De Soto worked in mining business in Chili and Peru.[1] Over the years, he engaged in mining business in Spain, North and South America, South Africa, and Mexico,[102][103][11] and was well known for his activity in the field.[112]

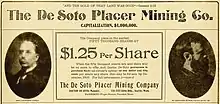

The De Soto Placer Mining Company was established in winter 1902–1903.[113] De Soto became its vice-president and general manager, and J. J. Habecker, a philanthropist from Philadelphia and De Soto's good friend, became the company's president.[102][107][114][48][16][17][15]

After securing grounds with rich deposits in Alaska, De Soto found investors from the East Coast for the De Soto Placer Mining Company. He also placed a large piece of the company's stock for sale, advertised it in newspapers, and raised up to $200,000 from it.[113][104][115][116] Home offices, and a large number of the majority stockholders of the company, were situated in Philadelphia.[107] Almost at once, the company became known as one of the best and largest mining companies in the world.[102][117][102]

Washington state mining

Sultan

De Soto had heard several stories about gold deposits in the Sultan River area.[39][10][36] In August 1899, he went up the river with a group of people, and after several days, they stumbled upon large and seemingly expensive, though abandoned, mining camps, known to the locals as Horseshoe Bend. The Sultan River area was actively prospected in the later 1880s and early 1890s, but was abandoned at the time of the Alaskan gold rush start in 1896.[118][36][119][120]

After several days of research, the team discovered placer gold in the soil.[118][121] The following year, De Soto researched areas up and down the river, securing a large number of mining claims. He also succeeded in involving investors from the East Coast for the venture.[118][101][119][122]

In 1901, De Soto secured 1,200 acres (490 ha) of land along the Sultan River with J. J. Habecker.[118][48] De Soto's company secured about 176 acres (71 ha) of placer land at Horseshoe Bend, and thanks to De Soto's activities, a hydraulic plant was installed there for about $15,000 ($403,000 in 2021 dollars[note 2]). De Soto's activity at Horseshoe Bend dissolved in 1902.[120][118]

De Soto's activity at the placer mining property near the Sultan River was considered the largest mining enterprise at the time.[123] By 1902, De Soto was well known in the mining circles of Washington state.[124]

In 1902 and 1903, De Soto and Habecker's partnership was referred to as a "large syndicate:" they owned and gold-mined more than 5,000 acres of Snohomish County. Several mining sites were developed in the Cascades, and around 50 men worked there. De Soto and Habecker also owned water rights for over 18 miles (29 km) of the 25-mile-long (40 km) Sultan River, which included nine waterfalls standing from 100 feet (30 m) 200 feet (61 m) high.[125][117]

In September 1903, De Soto and his companions turned the Sultan River from its course and sent its waters through a tunnel hewn though a solid rock. Then they worked to dry the remaining riverbed, aiming to find gold deposits and valuable gold nuggets. They found a considerable quantity of gold. However, snow melt later destroyed all the machinery and clogged the tunnel with boulders and timber.[126][123] On the other hand, one article stated that they themselves destroyed the dam, slowly suspended operations in the area, and dissolved partnerships with the company's small stock holders.[10]

De Soto continued working on the Sultan River property. In 1909,[112] he still took active part in prospecting new lands, and once was badly injured and almost killed in a rock slide.[112]

Granite Falls

In 1902, De Soto bought the Wayside mine in Granite Falls, Washington,[127] which was rich in quartz,[48] copper, silver, and gold.[128][29][107] He soon divided the shares with J. J. Habecker and other Philadelphian businessmen. They developed the mine and made a profit of $40,000 ($1,000,000 in 2021 dollars[note 2]) within the first few months.[127][124]In 1903, profit from the Granite Fall mines was dedicated exclusively for charity and to fund the Wayside Mission Hospital in Seattle.[48][29][107] By 1906, the Wayside mine in Granite Falls was owned by a stock company managed by Habecker.[127]

In 1903, De Soto widened his activities in the Granite Falls area. He platted a new town, planning to call it Wayside, and spent $17,000 ($500,000[note 2]) on other mines in Granite Falls, which he stated to be "the cheapest proposition he had ever developed." The new mine was 2,000 feet (610 m) lower than other Pacific Coast mines, which in De Soto's opinion increased the odds of finding rich deposits. A large number of miners were hired to work in Granite Falls, and professional machinery brought for the purpose.[129]

Alaska

Starting in 1900, De Soto prospected Alaskan grounds, including the area opposite Council City. In 1902, De Soto travelled to Council City and bought 2,120 acres (860 ha) of land opposite the town for the De Soto Placer and Mining Company. The lands were widely known for their rich deposits of pay gravel (gravel with a high concentration of gold and other precious metals), and were in fact considered the best in the world in terms of mining at the time. Many businessmen passed on the opportunity to invest there, as it was a very large operation and demanded large investments. Several mining magnates eventually lost the opportunity to develop the area due to their procrastination in regard to purchase, but De Soto was confident in the success of the mining activity in the area from the start.[113][102][130][131][104]

After securing ground opposite Council City and increasing the company's stock, the De Soto Placer and Mining Company kept buying more mining property (by 1903 the company owned about 4,000 acres (1,600 ha) of land) and invested over $100,000 ($3,000,000 in 2021 dollars [note 2]) in mining machinery and equipment, including electric dredgers, steam shovels, and ten river barges. One of the best-known machines ordered by the company was a dredger from Hammond Company in Portland, Oregon (for $83,000)[109] ($2,200,000[note 2]) and a large steam shovel.[113][104][102][103][106][16] At the time, the dredger and steam placer shovel were considered the largest in the world.[117][16] The company also owned and operated the steamships Aurum[102][103] and Nugget.[16][16]

In April 1903, De Soto chartered the steamer Jeanie to transport all of the company's machinery, equipment, and workers from Seattle to Golovnin Bay, and from there to Council City. The steamship's cargo, which weighed 1,300 tons, also included everything needed to outfit a 20-bed hospital, which De Soto later built in Council City. It was considered the largest cargo to have ever been shipped to Alaska, and the placer mining outfit was praised as the most complete of its time.[106][132][107][105][16][17] Led by De Soto, the party on board Jeannie consisted of about 80 men, all workers of different capacity for the De Soto Placer and Mining Company.[113][16] Additionally, 500 tons of general freight was shipped on two schooners, the Seven Sisters and the Martha W. Tuft.[16] Jeanie left Seattle on June 1, and by July 28 the cargo was successfully transported up the rivers from Golovnin Bay to the premises at Council City.[17][15][133]

Upon his arrival to Council, De Soto acquired more grounds to work on, including area suitable for hydraulicking (the use of water under pressure to dislodge minerals and other material).[105][114] By the end of August, the company's equipment and machinery, including the famous dredger and steam shovel, were installed and the majority of it functioning.[133][113][109][105][133] The remaining machinery started to operate during the winter of 1903–1904.[109][114] In 1904, De Soto's famous dredger was in operation for eighteen hours a day generating $1,500 ($40,000[note 2]) in gold daily.[109]

De Soto was considered the first to introduce dredge mining in the Council City area.[134]

De Soto Mining Company downfall

In 1904, despite the fact that all previous surveys and prospecting showed the richness of the De Soto Company's grounds, and despite the management's complete confidence in success,[17][15][105][133][114] later on only spots of rich deposits were found, and the company started experiencing problems.[113] The company received a lawsuit regarding bankruptcy from one of their smaller investors, but it was soon dismissed in court.[114]

Still, Alaskan management led by De Soto needed more funding to operate in 1904 and they asked Habecker, president of the De Soto Placer Mining Company, for additional investments. Habecker, who expected Alaskan property to earn the company thousands of dollars in the 1904 mining season, did not provide the money, but instead headed to Alaska to manage the business himself. Meanwhile, Alaskan managers borrowed $21,000 ($600,000 in 2021 dollars[note 2]) from the Bank of Nome leaving a bill of sale for the dredger and steam shovel as a pledge.[113][114] A series of unsuccessful moves were made to receive additional funding and find money to pay the company's debts. The Bank of Nome eventually took the company's dredger, later selling it to the Northern Light Mining Company for about $31,000 ($800,000[note 2]).[113]

Habecker noted mismanagement on De Soto and other Alaskan managers' parts and upon his arrival to Alaska applied to the court to appoint a receiver for the company. The receiver was appointed, but at this point the company's debt was appraised at about $125,000 (3,000,000[note 2]), the majority in debt to laborers.[113]

Later mining activity

Despite the fact that his company's downfall was later referred to as a disaster,[135] De Soto was still largely engaged in the mining business in Alaska and California in 1906.[5] With the help of Eskimos, De Soto found Itak Mountain, known as a rich deposit of cinnabar, for which he had been searching a long time. He became the first man to find cinnabar deposits in the Council City district. Together with a companion, Axel Young, De Soto secured 22 claims. Later, De Soto also discovered hot springs with medicinal properties.[136]

In 1906, De Soto was still highly appraised in mining circles and was said to be immensely wealthy.[5]

Other mining activity

De Soto was the biggest shareholder of the Philadelphia Crude Ore Company, located on Unalaska Island; it was considered the biggest sulphur deposit of the time. He was the majority share-holder and president of the Alaska Iron Company, which owned properties near Haynes Mission and sold 50 million tons of iron to great profit.[18]

Transportation business (1902–1903)

Snohomish County railway system

Along with mining, De Soto was successful in the railroad business.[18] In 1902, De Soto was granted a "blanket" franchise from the Board of Snohomish County Commissioners to build, maintain, and operate water power plants and an electric railway system (railroads, trolley and other lines), extending it to any part of Snohomish County. De Soto and his companions, including J. J. Habecker (his partner in other establishments in Washington and Alaska[48][29]) also acquired a franchise for an electric road between Everett and Snohomish. They were ready to invest $5,000,000 ($130,000,000 in 2021 dollars[note 2]) in the enterprise, and first required to provide a bond of $10,000 ($300,000[note 2]) as evidence of good faith. Work on the 20-mile (32 km) electric road was to begin in the six months following franchise acquisition.[137][124][138]

For this project, De Soto founded the Everett & Snohomish Rapid Transit Company. In 1902, De Soto and Habecker owned water rights for over 18 miles (29 km) of the 25-mile-long (40 km) Sultan River, including nine waterfalls standing from 100 feet (30 m) 200 feet (61 m) feet high. The partners decided to use that water power for the future railroad.[18][125] By the time they acquired all the necessary franchises, the construction for five wooden rockfilled dams and one steel dam on the Sultan River had already started.[124]

The plans of the new railroad system were ambitious: an eight-mile line between Everett and Snohomish, 76 miles (122 km) dragged to Seattle, and later stretched east to Sultan.[18][138][139] On June 17, 1902, the survey for the new railway line began in Sultan, and was to end in Everett. Construction work was to begin in Lowell (outskirts of Everett), connecting to Everett via the already-existing Everett Street Railway and Electric Company's line. The company had granted De Soto line-transit privileges.[138][140][139]

In April 1903, it was stated that the construction works for the Everett-Snohomish line seriously interfered with traffic in the area and that the franchise had never been secured by the promised bond of $10,000 ($300,000[note 2]). County commissioners prepared a lawsuit to stop the construction.[141]

Transportation in Alaska

In 1902, the Bering Sea & Council City Mining Company was incorporated, and De Soto became one of its officers. That same year, the company outlined the construction of the Bering Sea & Council City Railway, of which De Soto was president. He personally managed the topographical surveys.[142][18]

The company received a grant from the government to build 80 miles (130 km) of railroad, starting in Nome and ending at the Niukluk River near Council City. The road tan through land considered to be the richest mining property in Alaska. Later, the road's route was changed to extend to Chinick (later Golovin, Alaska). De Soto believed the railroad would spur the commercial growth of Northwestern Alaska. Although there were small railway lines in the area, the new road was considered the first railroad in Northwestern Alaska. When planning was complete, the railroad was appraised at $7,000,000 ($200,000,000 in 2021 dollars[note 2]).[142][143]

In 1903, De Soto owned the De Soto Transportation Company, which owned and operated the river steamer Aurum and a number of barges working the 60-mile (97 km) route between Golovnin Bay and Council City.[18]

Other businesses

In 1907, the Bering Sea Commercial Company was established to engage in the Bering Sea whaling business with capital of $5,000,000 ($130,000,000[note 2]) from investors from Chicago. De Soto sold some valuable land to the company and became its promoter and general manager.[19][20]

Personal life

In early life, De Soto travelled the world extensively, visiting Germany, Sweden, France, Chile, Peru, and England, until he finally settled in New York and then in Seattle. Prior to settling in Seattle, De Soto had briefly visited the city in 1867. De Soto also owned a house in Boston.[1]

As De Soto was a surgeon in Alaska in 1867, for a period of time it was believed that he was the oldest Alaskan pioneer in Seattle, but in 1904, another Alaskan pioneer, Fred M. Smith, claimed this title (he worked as superintendent for the Western Union Company's telegraph line in Alaska in 1865).[27]

According to an article printed during De Soto's life, he married a daughter of former Senator Jesse Crane and had two children, a daughter and son, both of whom died young from black diphtheria. De Soto's wife lost her mind and was put in a private asylum.[10] On the other hand, later articles reported that De Soto married a woman named Irene De Soto,[14] and had a daughter, Ruth De Soto Herold, who lived longer than her father and resided in Honolulu in 1960.[30]

In his early years, De Soto was acquainted with Giuseppe Garibaldi.[22][21][25]

In 1898, De Soto joined the Tabernacle Baptist Church in Seattle.[2][6][41] In 1900, he co-founded the Seattle Benevolent Society.[61]

In 1906, De Soto set the record for the largest polar bear skin ever brought from Alaska. Its length was 11.7 feet (3.6 m). Several bidders tried to buy it from De Soto for sums up to $1,000 ($30,000 in 2021 dollars[note 2]), but he kept it.[144]

De Soto was attacked by robbers several times during his life. In 1911, he was shot in the leg on the street by a stranger who attempted to rob him. De Soto testified that he had seen the man before, but the criminal wasn't caught and supposedly left town after the attack.[145] In 1902, De Soto was robbed again; afterwards, he got a gun permit and bought a gun. In 1925, De Soto was again attacked by four men in San Francisco, and shot one of them dead. Later, he was attacked by robbers in South Brooklyn; De Soto was unarmed, and the criminals took $185 from him. Two men were eventually charged with the crime and confessed.[24][13]

At the age of 93 in 1934, De Soto received a suspended jail sentence for five days for disorderly conduct after interfering with police activity while they were trying to arrest De Soto's employee.[146]

Death

De Soto died on November 11, 1936, after falling overboard into Brooklyn's Gowanus Bay in New York. At the time, he worked as dietician on the private yacht Centaur. He left the yacht for a shore visit and fell into the water while coming back. He died in an ambulance on the way to Norwegian Hospital. He was buried in Seattle.[13][12][14]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 De Soto's birth in Spanish Territories is confirmed by multiple sources.[2][3][4][5][6][7] According to Prosser, co-founder of the Washington State Historical Society, DeSoto was born in the Caroline Islands.[1] However, there are sources which give different locations of DeSoto's birth as the Canary Islands[8][9] and Barcelona, Spain.[10] These sources are likely erroneous, confusing the Canary and Caroline Islands in the former case, and confusing DeSoto's place of birth with his place of education (Barcelona) in the latter, as at the time of De Soto's birth, his father was the governor of Caroline Islands,[1] and De Soto was later brought to Spain and educated near Barcelona.[11]

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 The approximate value converted to 2021 dollars, based on a standard adjustment of the 1913 dollar value using the Consumer Price Index as calculated by United States Department of Labor.[63]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Prosser 1903, v.II, p. 47.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Warren 1980, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Philadelphia Times; Nov 7, 1897.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Oct 28, 1900.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Morning Oregonian; Oct 20, 1906.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bagley 1916, v.I, p.331.

- 1 2 3 4 Hunt & Kaylor 1917, v.I, p. 268.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tewkesbury 1974.

- 1 2 3 4 Herbert 1960.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Salem Times Register; Oct 23, 1903.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Devine 1905, p. 287.

- 1 2 The Courier-Journal; Nov 13, 1936.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Brooklyn Times Union; Nov 12, 1936.

- 1 2 3 Brooklyn Daily Eagle; Nov 14, 1936.

- 1 2 3 4 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Jul 28, 1903.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Jun 1, 1903.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Jun 2, 1903.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Prosser 1903, v.II, p. 48.

- 1 2 New York Times; Jun 16, 1907.

- 1 2 3 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Dec 16, 1907.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Philadelphia Times; Oct 24, 1897.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Boston Daily Globe; Oct 18, 1897.

- 1 2 Seattle Republican; Aug 19, 1910.

- 1 2 3 The Standard Union; Dec 3, 1928.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Newark Daily Advocate; Oct 27, 1897.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Seattle Daily Times; Aug 3, 1900.

- 1 2 Seattle Daily Times; Nov 7, 1904.

- ↑ Savannah morning news; Dec 17, 1892.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 New York Times; Apr 20, 1903.

- 1 2 3 4 Page 1960.

- 1 2 Brooklyn Daily Eagle; Nov 7, 1897.

- ↑ New York Times; Nov 7, 1897.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 The Christian Herald; Jan 17, 1900.

- 1 2 3 4 5 The Christian Herald; Apr 18, 1900.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Christian Herald; May 20, 1903.

- 1 2 3 4 Baxter 1903a.

- 1 2 3 4 Seattle Daily Times; Mar 13, 1900.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Seattle Daily Times; Nov 16, 1901.

- 1 2 3 Haskin 1903, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Dorpat 2001.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hunt & Kaylor 1917, v.I, p. 269.

- 1 2 Seattle Daily Times; May 23, 1937.

- 1 2 3 4 Seattle Daily Times; Apr 12, 1904, p. 1.

- 1 2 Seattle Daily Times; Mar 27, 1922.

- 1 2 3 DeCoster 2010.

- ↑ Silvers 2019, p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Mar 26, 1903.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Seattle Daily Times; Apr 19, 1903.

- 1 2 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Mar 21, 1904.

- 1 2 3 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Apr 12, 1904.

- 1 2 3 4 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Apr 16, 1904.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Seattle Daily Times; Apr 12, 1904, p. 2.

- ↑ Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Apr 16, 1903.

- 1 2 3 Silvers 2019, p. 21.

- 1 2 Baxter 1902.

- 1 2 3 4 Seattle Daily Times; Jun 15, 1902.

- ↑ Seattle Daily Times; Apr 21, 1900.

- ↑ Seattle Daily Times; Jul 9, 1900.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bagley 1916, v.I, p.332.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Jun 29, 1902.

- 1 2 3 Seattle Daily Times; Feb 10, 1900.

- 1 2 The Christian Herald; Sep 19, 1900.

- ↑ Bureau of Labor 2020.

- 1 2 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Nov 19, 1901.

- ↑ Seattle Daily Times; Jan 24, 1902.

- 1 2 3 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Jun 7, 1903.

- 1 2 Seattle Daily Times; Jun 6, 1903.

- 1 2 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Jun 5, 1904.

- ↑ Seattle Daily Times; Jul 12, 1900.

- ↑ Seattle Daily Times; Aug 13, 1900.

- ↑ Seattle Star; Oct 29, 1901.

- ↑ Seattle Post-Intelligencer; May 15, 1901.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Feb 1, 1903.

- 1 2 Seattle Daily Times; Jun 20, 1902b.

- ↑ Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Jul 22, 1902.

- ↑ Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Jun 20, 1902.

- ↑ Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Sep 7, 1902.

- ↑ Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Apr 1, 1903.

- 1 2 Oregon Daily Journal; Apr 14, 1904.

- ↑ Northwest Medicine; Nov 1, 1904, p. 497.

- 1 2 3 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; May 17, 1903a.

- 1 2 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Apr 26, 1903.

- 1 2 Seattle Daily Times; May 3, 1903.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; May 17, 1903b.

- 1 2 3 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; May 19, 1903.

- ↑ Seattle Daily Times; May 6, 1903.

- 1 2 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; May 8, 1903.

- 1 2 3 Seattle Daily Times; May 8, 1903.

- ↑ Seattle Post-Intelligencer; May 21, 1903.

- 1 2 3 Seattle Republican; May 22, 1903.

- ↑ Seattle Post-Intelligencer; May 22, 1903.

- 1 2 3 Halvorsen 2018.

- ↑ Seattle Daily Times; Apr 9, 1903, pp. 1, 3.

- ↑ Medical Sentinel; Apr 1, 1903, pp. 247–248.

- ↑ Seattle Daily Times; Apr 12, 1904, pp. 1–2.

- 1 2 Hardin 1913.

- ↑ Seattle Daily Times; Nov 9, 1906, p. 99.

- ↑ Newell 1960, pp. 97–99.

- ↑ Carey 1965, pp. 76–80.

- ↑ Northwest Medicine; Jan 1, 1907, p. 99.

- 1 2 Seattle Star; Dec 12, 1901.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Seattle Daily Times; Mar 22, 1903.

- 1 2 3 4 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Mar 22, 1903b.

- 1 2 3 4 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Apr 5, 1903c.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Aug 28, 1903.

- 1 2 3 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Apr 5, 1903a.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; May 13, 1903.

- ↑ The Christian Herald; Dec 14, 1904.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Oct 24, 1903.

- ↑ Existing Conditions Report; Oct 1, 2008, 2.11, pp.8-9.

- ↑ Steig 2018.

- 1 2 3 Seattle Daily Times; Sep 19, 1909.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Aug 1, 1904.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; May 30, 1904.

- ↑ Seattle Daily Times; Mar 29, 1903.

- ↑ Baxter 1903b.

- 1 2 3 The Pacific Monthly; Feb 1, 1903.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Apr 20, 1901.

- 1 2 Hunt 1916, v.I, p. 246.

- 1 2 Shiach & Averill 1906, p. 412.

- ↑ Haskin 1903, pp. 5–7.

- ↑ Haskin 1903, p. 7.

- 1 2 Hunt & Kaylor 1917, v.I, p. 399.

- 1 2 3 4 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; May 25, 1902.

- 1 2 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Mar 12, 1902.

- ↑ Seattle Daily Times; Sep 2, 1903.

- 1 2 3 Shiach & Averill 1906, p. 408.

- ↑ Shiach & Averill 1906, p. 407.

- ↑ Seattle Daily Times; Jan 24, 1903.

- ↑ Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Oct 11, 1902.

- ↑ San Francisco Call; Oct 14, 1902.

- ↑ Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Apr 5, 1903b.

- 1 2 3 4 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Aug 30, 1903.

- ↑ Devine 1905, pp. 286–287.

- ↑ Devine 1905, p. 288.

- ↑ Seattle Daily Times; Oct 14, 1906.

- ↑ Seattle Post-Intelligencer; May 28, 1902.

- 1 2 3 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Jun 10, 1902.

- 1 2 Seattle Daily Times; Jun 20, 1902a.

- ↑ Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Jun 18, 1902.

- ↑ Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Apr 30, 1903.

- 1 2 Seattle Post-Intelligencer; Mar 22, 1903a.

- ↑ Seattle Daily Times; Jul 27, 1903.

- ↑ Seattle Daily Times; Nov 9, 1906.

- ↑ Seattle Daily Times; Feb 22, 1911.

- ↑ The Miami News; Feb 15, 1934.

Literature cited

- "CPI Inflation Calculator", Bureau of Labor Statistics, Washington: United States Department of Labor, retrieved December 16, 2020

- "How to spend $3,000,000", Savannah morning news, Savannah: Theo. Blois & Co., p. 2, December 17, 1892, LCCN sn82015132, OCLC 57700813, retrieved June 1, 2020

- "Bowery mission argonauts", Boston Daily Globe, Boston: Globe Pub. Co., p. 14, October 18, 1897, ISSN 2572-1828, LCCN sn83045484, OCLC 9497068, retrieved June 1, 2020

- "Carry the gospel to the klondike", Philadelphia Times, Philadelphia: Frank McLaughlin, p. 24, October 24, 1897, LCCN sn84026094, OCLC 10288632, retrieved June 1, 2020

- "Gospel and gold", Newark Daily Advocate, Newark: John A. Caldwell, p. 3, October 27, 1897, LCCN sn84028851, OCLC 11498901, retrieved June 1, 2020

- "Klondike missionaries", Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn: I. Van Anden, p. 19, November 7, 1897, ISSN 2577-9397, LCCN sn83031151, OCLC 9817881, retrieved May 29, 2020

- "Wayside Talks", Philadelphia Times, Philadelphia: Frank McLaughlin, p. 6, November 7, 1897, LCCN sn84026094, OCLC 10288632, retrieved June 1, 2020

- "The sufferers in Alaska", New York Times, New York: H.J. Raymond & Co, p. 1, November 7, 1897, ISSN 0362-4331, LCCN sn78004456, OCLC 1645522

- De Witt Talmage, Thomas, ed. (January 17, 1900), "Seattle's Wayside Mission", The Christian Herald, New York: Christian Herald, vol. 23, p. 47, LCCN sf86007029, OCLC 1781778

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (February 10, 1900), "A hospital ship", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 3, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 3, 2021

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (March 13, 1900), "Big fleet in port", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 7, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 3, 2021

- De Witt Talmage, Thomas, ed. (April 18, 1900), "A Hospital Mission Ship", The Christian Herald, New York: Christian Herald, vol. 23, p. 337, LCCN sf86007029, OCLC 1781778

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (April 21, 1900), "Took a cold bath", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 2, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 3, 2021

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (July 9, 1900), "Jumped in the bay", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 5, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 3, 2021

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (July 12, 1900), "For care of the "fiends"", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 8, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 3, 2021

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (August 3, 1900), "On the old Idaho", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 7, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 3, 2021

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (August 13, 1900), "Sale of opiatos restricted", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 8, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 3, 2021

- De Witt Talmage, Thomas, ed. (September 19, 1900), "Seattle's "Wayside Mission"", The Christian Herald, New York: Christian Herald, vol. 23, p. 776, LCCN sf86007029, OCLC 1781778

- "Dr. De Soto and his work", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 18, October 28, 1900, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved May 29, 2020

- "Placer gold near Sultan", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 12, April 20, 1901, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 3, 2021

- "Forge doctor's name", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 10, May 15, 1901, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 3, 2021

- "De Soto may lose his job", Seattle Star, Seattle: E. W. Scripps, vol. 3, no. 212, p. 3, October 29, 1901, ISSN 2159-5577, LCCN sn87093407, OCLC 17285351, retrieved May 29, 2020

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (November 16, 1901), "Wayside mission work", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 7, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 3, 2021

- "To construct the gridiron", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 14, November 19, 1901, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 3, 2021

- "Elopement of morphine user from Dr. De Soto's ranch with a girl but half his age", Seattle Star, Seattle: E. W. Scripps, vol. 3, no. 250, p. 1, December 12, 1901, ISSN 2159-5577, LCCN sn87093407, OCLC 17285351, retrieved May 29, 2020

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (January 24, 1902), "Storm - hospital ship", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 13, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Gold mining camp in Cascade mountains on property controlled by large syndicate", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 6, March 12, 1902, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved May 29, 2020

- "Asks a franchise", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 11, May 25, 1902, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Given franchise for electrics", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 9, May 28, 1902, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Will start work", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 8, June 10, 1902, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (June 15, 1902), "To cost the city nothing", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 8, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "To begin survey of trolley line", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 9, June 18, 1902, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (June 20, 1902), "Fight with maddened deer", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 2, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (June 20, 1902), "Use of hospital ship", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 7, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "City to own hospital", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 8, June 20, 1902, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Offers to care for city sick", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 20, June 29, 1902, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Care for sick", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 6, July 22, 1902, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Wayside mission report", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 5, September 7, 1902, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Buys rich tract", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 7, October 11, 1902, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Steam shovels to scoop gold", San Francisco Call, San Francisco: John D. Spreckles, p. 10, October 14, 1902, ISSN 1941-0719, LCCN sn85066387, OCLC 13146227, retrieved June 1, 2020

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (January 24, 1903), "Strikes it rich", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 4, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Poor need care fail to get it", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 5, February 1, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Bittle Wells, William, ed. (February 1, 1903), "Progress: A rich strike", The Pacific Monthly, Portland: The Pacific Monthly Publishing Co., vol. IX, p. 276, LCCN 10003695, OCLC 228710176

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (March 22, 1903), "The DeSoto Placer Mining Co.", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 40, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved May 28, 2020

- "Nome to Council", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 11, March 22, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved May 29, 2020

- "The De Soto Placer Mining Co.", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 39, March 22, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved May 29, 2020

- "Business men to investigate", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 5, March 26, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved May 29, 2020

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (March 29, 1903), "The De Soto placer mining company", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 33, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved May 28, 2020

- "For poor sick", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 5, April 1, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Coe, Henry Waldo; Hutchinson, Woods, eds. (April 1, 1903), "The Seattle Medical World", Medical Sentinel, Portland: The State Medical Societies of Oregon, Washington Idaho, Montana and Utah, vol. XI, no. 4, pp. 247–248, OCLC 50353301

- "Charters the steamer Jeanie", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 6, April 5, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "The de Soto Placer Mining Co.", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 23, April 5, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved May 28, 2020

- "Progress in the Council city district", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 34, April 5, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved May 28, 2020

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (April 9, 1903), "Goes back to the root of all evil", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, pp. 1, 3, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Will play for benefit of the Wayside mission", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 13, April 16, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved May 28, 2020

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (April 19, 1903), "Its profits for charity", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 5, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved May 28, 2020

- "Gold mine for charity", New York Times, New York: H.J. Raymond & Co, p. 1, April 20, 1903, ISSN 0362-4331, LCCN sn78004456, OCLC 1645522, retrieved May 29, 2020

- "Large home for Wayside mission", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 16, April 26, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Traffic blocked", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 9, April 30, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (May 3, 1903), "The proposed new Wayside mission hospital", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 24, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved May 28, 2020

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (May 6, 1903), "For thirty-five years", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 14, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (May 8, 1903), "Finds the street gone", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 4, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "City may not get hospital", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 5, May 8, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved May 29, 2020

- "Mine profits go to charity", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 5, May 13, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved May 29, 2020

- "A hospital offered", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 4, May 17, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Wants to build new hospital", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 23, May 17, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved May 29, 2020

- "Refused by city", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 7, May 19, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "How a Western mission crew", Christian Herald, New York: Christian Herald, vol. 26, p. 438, May 20, 1903, LCCN sf86007029, OCLC 1781778

- "Cannot lease street", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 7, May 21, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Why this apathy?", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 4, May 22, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Revels Cayton, Susie, ed. (May 22, 1903), "Tales of the town", Seattle Republican, Seattle: Republican Pub. Co., p. 3, ISSN 2157-3271, LCCN sn84025811, OCLC 10328970, retrieved May 29, 2020

- "Movement toward Nome begins today with several sailings", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 9, June 1, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved May 29, 2020

- "First crowds off for Nome", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 6, June 2, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (June 6, 1903), "Board of public works", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 4, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "May find a way", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 6, June 7, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (July 27, 1903), "New railroad project", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 4, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Expedition is great success", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 6, July 28, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Results in sight", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 5, August 28, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Machinery to take out gold", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 6, August 30, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (September 2, 1903), "Hoboes burn the camp", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 4, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "The Seattle spirit", Salem Times Register, Salem: Charles M. Webber, vol. 38, no. 21, p. 1, October 23, 1903, LCCN sn85026933, OCLC 12761431, retrieved June 1, 2020

- "Much work done in Council city district", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 27, October 24, 1903, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved May 29, 2020

- "Big audience at hospital benefit", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 12, March 21, 1904, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved May 29, 2020

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (April 12, 1904), "Seattle doctors fight de Soto", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, pp. 1, 2, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Dismissed from Wayside mission", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 14, April 12, 1904, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Jackson, Sam, ed. (April 14, 1904), "Medical trust wrecks charity", Oregon Daily Journal, Portland: Journal Print Co., p. 2, LCCN sn85042444, OCLC 12429002, retrieved May 29, 2020

- "Dr. Walter Everly gets appointment", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 10, April 16, 1904, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Dismiss bankruptcy charge", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 12, May 30, 1904, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Seattle's hospitals where sick are cared for great charitable work conducted by these institutions and what it costs", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 47, June 5, 1904, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved May 29, 2020

- "Receiver for the De Soto company", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 11, August 1, 1904, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Smith, Clarence A.; Eagleson, James B., eds. (November 1, 1904), "Medical notes: The Wayside Emergency Hospital", Northwest Medicine, Seattle: Washington Medical Library Association, vol. 2, no. 11, p. 497, LCCN sv88082506, OCLC 741711093

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (November 7, 1904), "Not the oldest pioneer", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 10, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "The light of the world", The Christian Herald, New York: Christian Herald, vol. 27, p. 1125, December 14, 1904, LCCN sf86007029, OCLC 1781778

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (October 14, 1906), "Eskimos uncover cinnabar", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 21, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Piper, Edgar B., ed. (October 20, 1906), "DeSoto's great-great-grandson pays a visit to city of Portland", Morning Oregonian, Portland: Oregonian Media Group, p. 16, ISSN 8750-1317, LCCN sn83025138, OCLC 9278209, retrieved June 1, 2020

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (November 9, 1906), "Largest bear hide now in Queen city", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 9, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Smith, Clarence A.; Eagleson, James B., eds. (January 1, 1907), "Medical notes: The Wayside Hospital of Seattle", Northwest Medicine, Seattle: Washington Medical Library Association, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 99, LCCN sv88082506, OCLC 741711093

- "Chicago men after whales", New York Times, New York: H.J. Raymond & Co, vol. LVI, no. 18040, p. 9, June 16, 1907, ISSN 0362-4331, LCCN sn78004456, OCLC 1645522, retrieved May 29, 2020

- "Dr. De Soto has whaling project", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 14, December 16, 1907, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (September 19, 1909), "Pioneers' bravery still to be seen", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 60, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved May 28, 2020

- Revels Cayton, Susie, ed. (August 19, 1910), "State and King county candidates seeking nomination", Seattle Republican, Seattle: Republican Pub. Co., p. 5, ISSN 2157-3271, LCCN sn84025811, OCLC 10328970, retrieved May 29, 2020

- Blethen, Alden J., ed. (February 22, 1911), "Dr. Alex de Soto shot by thug who tries to rob him", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 1, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- "Heard at Main-o 300", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 6, March 27, 1922, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved May 28, 2020

- "Bandits discover tartar in 88-year-young victim", The Standard Union, Brooklyn: Bennett & Smith, p. 25, December 3, 1928, LCCN sn83030768, OCLC 9671762, retrieved May 29, 2020

- Cox, James M., ed. (February 15, 1934), "93-years-old man found disorderly", The Miami News, Miami: Metropolis Pub. Co., p. 17, LCCN sn83016280, OCLC 2733721, retrieved June 1, 2020

- "Yacht's doctor, 96, expires after falling into gowanus", Brooklyn Times Union, Brooklyn: Brooklyn Daily Times, p. 10, November 12, 1936, LCCN sn88075832, OCLC 18885943, retrieved June 1, 2020

- Watterson, Harvey Magee, ed. (November 13, 1936), "Fall overboard fatal to yacht doctor, 96", The Courier-Journal, Tysons Corner: Gannett, p. 30, ISSN 1930-2177, LCCN sn83045188, OCLC 6637888, retrieved June 1, 2020

- "Deaths", Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Brooklyn: I. Van Anden, p. 11, November 14, 1936, ISSN 2577-9397, LCCN sn83031151, OCLC 9817881, retrieved May 29, 2020

- "Early hospital was hull of wrecked ship", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 48, May 23, 1937, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved May 28, 2020

- Existing Conditions Report: Alaskan Way Seawall Replacement Project Feasibility Study Environmental Impact Statement — Existing Conditions, Washington: U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, October 1, 2008, OCLC 805222497

- Bagley, Clarence B. (1916), History of Seattle: From the Earliest Settlement to the Present Time, Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, LCCN 16011408, OCLC 7372062

- Baxter, Marion B. (February 16, 1902), Blethen, Alden J. (ed.), "The Wayside mission", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 6, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Baxter, Marion B. (April 26, 1903a), Blethen, Alden J. (ed.), "Praise for the living", Seattle Daily Times, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, p. 6, ISSN 2639-4898, LCCN sn86072007, OCLC 1765328, retrieved May 28, 2020

- Baxter, Marion B. (June 10, 1903b), "The De Soto placer mining co.", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 5, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved March 19, 2021

- Carey, Roland (1965), The Sound of Steamers, Seattle: Alderbrook Publishing Co., LCCN 65004298, OCLC 11094242

- DeCoster, Dotty (October 28, 2010), "400 Yesler Way: Seattle Municipal Building 1909-1916, Seattle Public Safety Building 1917-1951", HistoryLink, Seattle: History Ink, OCLC 124224498, retrieved June 2, 2020

- Devine, Edward James (1905), Across widest America, Newfoundland to Alaska, with the impressions of two years' sojourn on the Bering coast (PDF), Montreal: The Canadian messenger, LCCN 08029599, OCLC 1007012634, retrieved October 23, 2020

- Dorpat, Paul (September 30, 2001), "By the wayside", seattletimes.com, Seattle: The Seattle Times Company, OCLC 40409665, retrieved February 24, 2021

- Halvorsen, Douglass (January 19, 2018), Prats, J. J. (ed.), "Steamer Idaho Wreckage", hmdb.org, Powell: Historical Marker Database, retrieved February 24, 2021

- Hardin, Annette (April 20, 1913), "Captains of Seattle's army of trained nurses", Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Seattle: Leigh S. J. Hunt, p. 101, ISSN 2379-7304, LCCN sn83045604, OCLC 9563195, retrieved May 28, 2020

- Haskin, Frederic J. (August 29, 1903), "Strange Tales of Gold and Tears From Frozen Klondike Wilds", The Sunny South, Atlanta: John H. Seals, pp. 5, 7, LCCN unk83014347, retrieved June 1, 2020