| Mantled howler[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mantled howler calls, recorded in Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Atelidae |

| Genus: | Alouatta |

| Species: | A. palliata |

| Binomial name | |

| Alouatta palliata (Gray, 1849) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

Alouatta palliata aequatorialis | |

| |

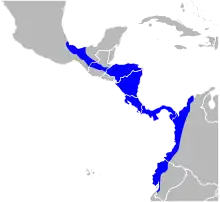

| Distribution of Alouatta palliata[4] | |

| Synonyms | |

The mantled howler (Alouatta palliata) is a species of howler monkey, a type of New World monkey, from Central and South America. It is one of the monkey species most often seen and heard in the wild in Central America. It takes its "mantled" name from the long guard hairs on its sides.

The mantled howler is one of the largest Central American monkeys, and males can weigh up to 9.8 kg (22 lb). It is the only Central American monkey that eats large quantities of leaves; it has several adaptations to this folivorous diet. Since leaves are difficult to digest and provide less energy than most foods, the mantled howler spends the majority of each day resting and sleeping. The male mantled howler has an enlarged hyoid bone, a hollow bone near the vocal cords, which amplifies the calls made by the male, and is the reason for the name "howler". Howling allows the monkeys to locate each other without expending energy on moving or risking physical confrontation.

The mantled howler lives in groups that can have over 40 members, although groups are usually smaller. Most mantled howlers of both sexes are evicted from the group they were born in upon reaching sexual maturity, resulting in most adult group members being unrelated. The most dominant male, the alpha male, gets preference for food and resting places, and mates with most of the receptive females. The mantled howler is important to the rainforest ecology as a seed disperser and germinator. Although it is affected by deforestation, it is able to adapt better than other species, due to its ability to feed on abundant leaves and its ability to live in a limited amount of space.

Taxonomy

The mantled howler belongs to the New World monkey family Atelidae, the family that contains the howler monkeys, spider monkeys, woolly monkeys and muriquis. It is a member of the subfamily Alouattinae and genus Alouatta, the subfamily and genus containing all the howler monkeys.[1][4] The species name is A. palliata; a pallium was a cloak or mantle worn by ancient Greeks and Romans.[5] This refers to the long guard hairs, known as a "mantle", on its sides.[6]

Three subspecies are recognized:[4]

- Ecuadorian mantled howler, Alouatta palliata aequatorialis, in Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Panama and Peru;

- Golden-mantled howler, Alouatta palliata palliata, in Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua;

- Mexican howler, Alouatta palliata mexicana, in Mexico and Guatemala.

Two additional subspecies of the mantled howler are sometimes recognised, but these are more generally recognised as subspecies of the Coiba Island howler, Allouatta coibensis. However, mitochondrial DNA testing of their status has been inconclusive:[4]

- Azuero howler, Alouatta palliata trabeata, in Panama;

- Alouatta palliata coibensis, in Panama.

Physical description

The mantled howler's appearance is similar to other howler monkeys of the genus Alouatta except for coloration. The mantled howler is primarily black except for a fringe of yellow or golden brown guard hairs on the flanks of the body earning the common name "mantled" howler monkey.[7] When the males reach maturity, the scrotum turns white.[8] Females are between 481 and 632 mm (18+7⁄8 and 24+7⁄8 in) in body length, excluding tail, and males are between 508 and 675 mm (20.0 and 26.6 in). The prehensile tail is between 545 and 655 mm (21.5 and 25.8 in) long. Adult females generally weigh between 3.1 and 7.6 kg (6+7⁄8 and 16+3⁄4 lb), while males typically weigh between 4.5 and 9.8 kg (9 lb 15 oz and 21 lb 10 oz).[8] Average body weights can vary significantly between monkey populations in different locations.[9] The brain of an adult mantled howler is about 55.1 g (1+15⁄16 oz), which is smaller than that of several smaller monkey species, such as the white-headed capuchin.[8][10]

The mantled howler shares several adaptations with other species of howler monkey that allow it to pursue a folivorous diet, that is, a diet with a large component of leaves. Its molars have high shearing crests, to help it eat the leaves,[11] and males have an enlarged hyoid bone near the vocal cords.[12] This hyoid bone amplifies the male mantled howler's calls, allowing it to locate other males without expending much energy.[12]

Behavior

Social structure

The mantled howler lives in groups. Group size usually ranges from 10 to 20 members, generally 1 to 3 adult males and 5 to 10 adult females, but some groups have over 40 members.[11][13] Males outrank females, and younger animals of each gender generally have a higher rank than older animals.[12] Higher-ranking animals get preference for food and resting sites, and the alpha male gets primary mating rights.[12] Animals in the group are generally not related to each other because most members of both sexes leave the group before sexual maturity.[11]

Grooming activity in the mantled howler is infrequent and has been shown to reflect social hierarchy, with dominant individuals grooming subordinates.[14][15] Most grooming activities are short and are typically females grooming infants or adult males.[16] Aggressive interactions between group members are not often observed either.[14] However, studies have shown that aggressive interactions among group members do occur, and are probably not often observed because these interactions tend to be quick and silent.[14]

Mantled howler groups that have been studied have occupied home ranges of between 10 and 60 hectares (25 and 148 acres).[11] Groups do not defend exclusive territories, but rather several groups have overlapping home ranges.[12] However, if two groups meet each group will aggressively attempt to evict the other.[12] On average, groups travel up to about 750 metres (2,460 ft) each day.[11]

The mantled howler has little interaction with other sympatric monkey species but interactions with the white-headed capuchin sometimes occur. These are most often aggressive, and the smaller capuchins are more often the aggressors.[17] However, affiliative associations between the capuchins and howlers do sometimes occur, mostly involving juveniles playing together, and at times the capuchins and howlers may feed in the same tree, apparently ignoring each other.[17]

Diet

The mantled howler is the most folivorous species of Central American monkey. Leaves make up between almost 50% and 75% of the mantled howler's diet.[11][13] The mantled howler is selective about the trees it eats from, and it prefers young leaves to mature leaves.[18] This selectivity is likely to reduce the levels of toxins ingested, since certain leaves of various species contain toxins.[18] Young leaves generally have fewer toxins, as well as more nutrients, than more mature leaves, and are also usually easier to digest.[11][18] Mantled howler monkeys possess large salivary glands that help break down the leaf tannins by binding the polymers before the food bolus reaches the gut.[16] Although leaves are abundant, they are a low energy food source.[12] The fact that the mantled howler relies so heavily on a low energy food source drives much of its behaviour – for example, howling to locate other groups and spending a large portion of the day resting.[12]

Although leaves tend to make up the majority of the mantled howler's diet, fruit can also make up a large portion of the diet. When available, the proportion of fruit in the diet can be as much as 50%, and can sometimes exceed the proportion of leaves.[11] The leaves and fruit from Ficus trees tend to be the preferred source of the mantled howler.[12] Flowers can also make up a significant portion of the diet and are eaten in particularly significant quantities during the dry season.[11][12] The mantled howler tends to get the water it needs from its food, drinking from tree holes during the wet season,[12] and by drinking water trapped in bromeliads.[19]

Like other species of howler monkeys, almost all mantled howlers have full three color vision.[20][21] This is different from other types of New World monkeys, in which most individuals have two color vision. The three color vision exhibited by the mantled howler is believed to be related to its dietary preferences, allowing it to distinguish young leaves, which tend to be more reddish, from more mature leaves.[20]

Locomotion

The mantled howler is diurnal and arboreal.[8] Movement within the rainforest canopy and floor includes quadrupedalism (walking and running on supports), bridging (crossing gaps by stretching), and climbing.[22] It will also sometimes leap to get to another limb.[23]

However, the mantled howler is a relatively inactive monkey. It sleeps or rests the entire night and about three quarters of the day. Most of the active period is spent feeding, with only about 4% of the day spent on social interaction.[23] This lethargy is an adaptation to its low energy diet.[12] It uses its prehensile tail to grasp a branch when sleeping, resting or when feeding.[24] It can support its entire body weight with the tail, but more often holds on by the tail and both feet.[24] A study has shown that the mantled howler reuses travel routes to known feeding and resting sites, and appears to remember and use particular landmarks to help pick direct routes to its destination.[25]

Communication

The mantled howler gets the name "howler" from the calls made by the males, particularly at dawn and dusk, but also in response to disturbances.[12] These calls are very loud and can be heard from several kilometers.[12] The calls consist of grunts and repeated roars that can last for four to five seconds each.[12] The volume is produced by the hyoid bone — a hollow bone near the vocal cords — amplifying the sound made by the vocal cords. Male mantled howlers have hyoid bones that are 25 times larger than similarly sized spider monkeys, and this allows the bone to act like the body of a drum in amplifying the calls. Females also call but their calls are higher in pitch and not as loud as the males'.[12] The ability to produce these loud roars is likely an energy saving device, consistent with the mantled howler's low energy diet. The roars allow the monkey to locate each other without moving around or risking physical confrontations.[12] The mantled howler uses a wide range of other sounds, including barks, grunts, woofs, cackles and screeches.[19] It uses clucking sounds to maintain auditory contact with other members of its group.[26]

The mantled howler also uses non-vocal communication, such as "urine rubbing" when in a distressful social situation.[19] This consists of rubbing the hands, feet, tail and/or chest with urine.[19] It marks its scent by rubbing its throat on branches.[8] Lip smacking and tongue movements are signals used by females to indicate an invitation to mate.[19] Genital displays are used to indicate emotional states, and group members shake branches, which is apparently a playful activity.[19]

The mantled howler is usually indifferent to the presence of humans. However, when it is disturbed by people, it often express its irritation by urinating or defecating on them. It can accurately hit its observers despite being high in the trees.[12]

Tool use

The mantled howler has not been observed using tools, and prior to 1997 no howler monkey was known to use tools. However, in 1997 a Venezuelan red howler (Alouatta seniculus) was reported to use a stick as a club to hit a Linnaeus's two-toed sloth, (Choloepus didactylus), that was resting in its tree.[27] This suggests that other howlers, such as the mantled howler, may also use tools in ways that have not yet been observed.

Reproduction

The mantled howler uses a polygamous mating system in which one male mates with multiple females.[19] Usually, the alpha male monopolises the breeding opportunities, but if the alpha male is distracted, a lower-ranking male can get an opportunity to mate.[12] And in some groups, lower-ranking males do get regular mating opportunities and do sire offspring.[11][28] Alpha males generally maintain their status for about 2+1⁄2 to 3 years, during which time they may father 18 or so infants.[8] Females become sexually mature at 36 months, males at 42 months.[19] Females reaching sexual maturity are typically 42 months old by their first birth. They undergo a regular estrus cycle, with an average duration of 16.3 days, and display sexual skin changes, particularly swelling and color change (from white to light pink) of the labia minora.[29] The copulatory sequence begins when a receptive female approaches a male and engages in rhythmic tongue flicking. The male responds with the same tongue movements before the female turns while elevating her rump, which allows for mating to begin.[12][19][30] Females apparently also use chemical signals, since males smell the females' genitals and taste their urine.[19] The gestational period is 186 days; births can occur at any time of year.[19] The infant's fur is silver at birth, but turns pale or gold after a few days. After that, the fur starts to darken, and the infant takes on the adult coloration at about 3 months old.[12]

The infant is carried under its mother, clinging to its mother's chest, for the first 2 or 3 weeks of its life.[19] After that, it is carried on its mother's back.[19] At about 3 months the mother will usually start to push the infant off, but will still carry the infant some of the time until it is 4 or 5 months old.[12] After the young can move on its own, the mother will carry it across difficult gaps in the trees.[19] Juveniles play among themselves much of the time.[19] Infants are weaned at 1+1⁄2 years old at which point maternal care ends.[19] Adult females typically give birth every 19 to 23 months, assuming the prior infant survived to weaning.[11]

The mantled howler differs from other howler monkey species in that the males' testes do not descend until they reach sexual maturity.[16] Upon reaching sexual maturity, the young monkeys are usually evicted from their natal group, although the offspring of a high-ranking female may get to stay in its natal group.[12] However, many infants do not reach sexual maturity; high-ranking adults sometimes harass or kill the offspring of lower-ranking monkeys to eliminate competition to their own offspring for an opportunity to remain with the group upon reaching maturity.[12] Natal emigration is performed by both sexes, with 79% of all males and 96% of the females leaving their original social group.[31] When a male from outside the group ousts the previous alpha male, he normally kills any infants so that the mothers come into estrus quickly and are able to mate with him.[11] Predators, such as cats, weasels, snakes and eagles, also kill infants.[12] As a result, only about 30% of mantled howler infants live more than one year.[6] The highest reproductive success occurs in the middle-ranking females, with the alpha position lower possibly because of competitive pressures, and infant mortality appears to be lower when the timing of births in a group of females is clustered.[29] If it survives infancy, the mantled howler's lifespan is typically 25 years.[6]

Distribution and habitat

The mantled howler is native to Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama and Peru.[4] Within Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama, the mantled howler is found in locations throughout the countries.[4] In Colombia and Ecuador, it is found in a narrow corridor bordered by the Pacific Ocean to the west and the Andes Mountains to the east and also in Colombia in a small area near the Caribbean Sea close to the Panama border.[4] In Guatemala, the mantled howler is found through the central part of the country, and into southeastern Mexico south of the Yucatán Peninsula.[4] The mantled howler is among the most commonly seen and heard primates in many Central American national parks, including Manuel Antonio, Corcovado, Monteverde and Soberania.[13][32] The mantled howler lives in several different types of forest, including secondary forest and semi-deciduous forest but is found in higher densities in older areas of forest and in areas containing evergreen forest.[33][34] The mantled howler is sympatric with another howler monkey species, the Guatemalan black howler, A. pigra, over a small part of its range, in Guatemala and Mexico near the Yucatan Peninsula.[4]

Conservation status

The mantled howler is regarded as vulnerable from a conservation standpoint by the IUCN.[2] Its numbers are adversely affected by rainforest fragmentation which has caused forced relocation of groups to less habitable regions, as well as deforestation and capture for the pet trade.[2]

In 2011, the primatologist Joaquim Veà Baró studied in Los Tuxtlas Biosphere Reserve in Veracruz, Mexico, the impact due to the fragmentation of populations and identified an increase in stress, especially among females, when a male from outside the group approached the area, because they felt that their offspring are being threatened.[35] In addition, food limitation in areas of reduced surface area was forcing individuals to adapt their diet to increased food deprivation. Veà highlighted that “although this situation revealed up to what point individuals have the capacity for adaption, in some cases, undernourishment can lead to health problems that would make the population inviable”. Results can be compared to humans who “do not always eat everything which they should, for example in underdeveloped countries that have problems with malnutrition, rickets, a range of illnesses, but this does not put an end to the population, but rather provokes them to change their characteristics”.[36]

However, the mantled howler can adapt to forest fragmentation better than other species due to its low energy lifestyle, small home ranges and ability to exploit widely available food sources.[37] The mantled howler is important to its ecosystems for a number of reasons, but especially in its capacity as a seed disperser and germinator, since passing through the monkey's digestive tract appears to aid the germination of certain seeds.[12] Dung beetles, which are also seed dispersers as well as nutrient recyclers, also appear to be dependent on the presence of the mantled howler.[12] The mantled howler is protected from international trade under Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).[38]

References

- 1 2 Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Primates". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 3 Cortes-Ortíz, L.; Rosales-Meda, M.; Williams-Guillén, K.; Solano-Rojas, D.; Méndez-Carvajal, P.G.; de la Torre, S.; Moscoso, P.; Rodríguez, V.; Palacios, E.; Canales-Espinosa, D.; Link, A.; Guzman-Caro, D.; Cornejo, F.M. (2021). "Alouatta palliata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T39960A190425583. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T39960A190425583.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Rylands, A.; Groves, C.; Mittermeier, R.; Cortes-Ortiz, L. & Hines, J. (2006). "Taxonomy and Distributions of Mesoamerican Primates". In Estrada, A.; Garber P.; Pavelka M. & Luecke, L. (eds.). New Perspectives in the Study of Mesoamerican Primates. New York: Springer. pp. 47–55. ISBN 978-0-387-25854-6.

- ↑ "Pallium". American Heritage Dictionary. Retrieved 2009-02-21.

- 1 2 3 Henderson, C. (2000). Field Guide to the Wildlife of Costa Rica. Austin, Tex.: Univ. of Texas Press. pp. 450–452. ISBN 0-292-73459-X.

- ↑ Glander, Ken (1983). Costa Rican Natural History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 448–449.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rowe, N. (1996). The Pictorial Guide to the Living Primates. East Hampton, N.Y.: Pogonias Press. p. 109. ISBN 0-9648825-0-7.

- ↑ Glander, K. (2006). "Average Body Weight for Mantled Howling Monkeys (Alouatta palliata)". In Estrada, A.; Garber, P.; Pavelka, M.; Luecke, L. (eds.). New Perspectives in the Study of Mesoamerican Primates. New York: Springer. pp. 247–259. ISBN 978-0-387-25854-6.

- ↑ Rowe, N. (1996). The Pictorial Guide to the Living Primates. Pogonias Press. p. 95. ISBN 0-9648825-0-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Di Fiore, A. & Campbell, C. (2007). "The Atelines". In Campbell, C.; Fuentes, A.; MacKinnon, K.; Panger, M. & Bearder, S. (eds.). Primates in Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 155–177. ISBN 978-0-19-517133-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Wainwright, M. (2002). The Natural History of Costa Rican Mammals. Miami, FL: Zona Tropical. pp. 139–145. ISBN 0-9705678-1-2.

- 1 2 3 Reid, F. (1998). A Field Guide to the Mammals of Central America and Southeast Mexico. Oxford University Press, Inc. pp. 178–183. ISBN 0-19-506401-1.

- 1 2 3 Sussman, R. (2003). Primate Ecology and Social Structure Volume 2: New World Monkeys (Revised First ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Custom Publ. pp. 142–146. ISBN 0-536-74364-9.

- ↑ Jones, C. (1979). "Grooming in the Mantled Howler Monkey, Alouatta palliata (Gray)". Primates. 20 (2): 289–292. doi:10.1007/BF02373380. S2CID 29645045.

- 1 2 3 Kinzey, W. (1997). "Alouatta". In Kinzey, W (ed.). New World Primates Ecology, Evolution and Behavior. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. p. 184. ISBN 0-202-01186-0.

- 1 2 Rose, L.; Perry, S.; Panger, M.; Jack, K.; Manson, J.; Gros-Louis, J. & Mackinnin, K. (2003). "Interspecific Interactions between Cebus capucinus and other Species: Data from Three Costa Rican Sites" (PDF). International Journal of Primatology. 24 (4): 780–785. doi:10.1023/A:1024624721363. S2CID 430769. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-25. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- 1 2 3 Glander, K. (1977). "Poison in a Monkey's Garden of Eden". The Primate Anthology. Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall. pp. 146–152. ISBN 0-13-613845-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Defler, T. (2004). Primates of Colombia. Bogotá, D.C., Colombia: Conservation International. pp. 370–384. ISBN 1-881173-83-6.

- 1 2 Stoner, K.; Riba-Hernandez, P. & Lucas, P. (2005). "Comparative Use of Color Vision for Frugivory by Sympatric Species of Platyrrhines" (PDF). American Journal of Primatology. 67 (4): 399–409. doi:10.1002/ajp.20195. PMID 16342076. S2CID 41097897. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-25. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ↑ Dawkins, R. (2004). The ancestor's tale: a pilgrimage to the dawn of evolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 145–155. ISBN 978-0-618-00583-3.

- ↑ Gebo, D. (1992). "Locomotor and Postural Behavior in Alouatta palliata and Cebus capucinus". American Journal of Primatology. 26 (4): 277–290. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350260405. PMID 31948152. S2CID 86208363.

- 1 2 Nowak, R. (1999). Walker's Primates of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 103–105. ISBN 0-8018-6251-5.

- 1 2 Kavanagh, M. (1983). A Complete Guide to Monkeys, Apes and Other Primates. London: Cape. pp. 95–98. ISBN 0-224-02168-0.

- ↑ Garber, P. & Jelink, P. (2006). "Travel Patterns and Spatial Mapping". In Estrada, A.; Garber, P.; Pavelka, M. & Luecke, L. (eds.). New Perspectives in the Study of Mesoamerican Primates. New York: Springer. pp. 287–306. ISBN 978-0-387-25854-6.

- ↑ da Cunha, R.G.T. & Byrne, R. (2009). "The Use of Vocal Communication in Keeping the Spatial Cohesion of Groups: Intentionality and Specific Functions". In Garber, P.; Estrada, A.; Bicca-Marques, J.C.; Heymann, E. & Strier, K. (eds.). South American Primates: Comparative Perspectives in the Study of Behavior, Ecology and Conservation. Springer. pp. 344–345. ISBN 978-0-387-78704-6.

- ↑ Richard-Hansen, C.; Bello, N. & Vie, J. (1998). "Tool use by a red howler monkey (Alouatta seniculus) towards a two-toed sloth (Choloepus didactylus)". Primates. 39 (4): 545–548. doi:10.1007/BF02557575. S2CID 30385216.

- ↑ Di Fiore, A. (2009). "Genetic Approaches to the Study of Dispersal and Kinship in New World Primates". In Garber, P.; Estrada, A.; Bicca-Marques, J.C.; Heymann, E.; Strier, K. (eds.). South American Primates: Comparative Perspectives in the Study of Behavior, Ecology and Conservation. Springer. pp. 223–225. ISBN 978-0-387-78704-6.

- 1 2 Glander, Ken (1980). "Reproduction and Population Growth in Free-Ranging Mantled Howler Monkeys" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 53 (53): 25–36. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330530106. hdl:10161/6289. PMID 7416246.

- ↑ Young, O (1982). "Tree-rubbing Behavior of a Solitary Male Howler Monkey". Primates. 2 (23): 303–306. doi:10.1007/BF02381169. S2CID 23969557.

- ↑ Glander, Ken (1992). "Dispersal Patterns in Costa Rican Mantled Howling Monkeys". International Journal of Primatology. 4 (13): 415–436. doi:10.1007/BF02547826. hdl:10161/6402. S2CID 3030339.

- ↑ Hunter, L. & Andrew, D. (2002). Watching Wildlife Central America. Footscray, Vic.: Lonely Planet Publications. pp. 97, 100, 102, 130. ISBN 1-86450-034-4.

- ↑ Emmons, L. (1997). Neotropical Rainforest Mammals A Field Guide (Second ed.). Chicago, Ill.; London: Univ. of Chicago Pr. pp. 130–131. ISBN 0-226-20721-8.

- ↑ DeGama, H. & Fedigan, L. (2006). "The Effects of Forest Fragment Age, Isolation, Size, Habitat Type, and Water Availability on Monkey Density in a Tropical Dry Forest". In Estrada, A.; Garber, P.; Pavelka, M. & Luecke, L. (eds.). New Perspectives in the Study of Mesoamerican Primates. New York: Springer. pp. 165–186. ISBN 978-0-387-25854-6.

- ↑ Escalón, Edith (2006). "Reducción del hábitat 'estresa' a monos aulladores en Los Tuxtlas". Boletines Universitat Veracrucana (in Spanish) (núm. 1081). Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- ↑ Castillo Lagos, Susana (August 22, 2011). "Deforestación amenaza hábitat de monos aulladores en Los Tuxtlas". El periódico de los universitarios (in Spanish). Universitat Veracruzana (núm.450). Archived from the original on December 23, 2015. Retrieved December 21, 2015.

- ↑ Garber, P.; Estrada, A. & Pavelka, M. (2006). "Concluding Comments and Conservation Priorities". In Estrada, A.; Garber, P.; Pavelka, M. & Luecke, L. (eds.). New Perspectives in the Study of Mesoamerican Primates. New York: Springer. pp. 570–571. ISBN 0-387-25854-X.

- ↑ "Alphabetical Primate CITES Appendix I". AESOP-Project. Archived from the original on 2009-02-01. Retrieved 2009-02-10.