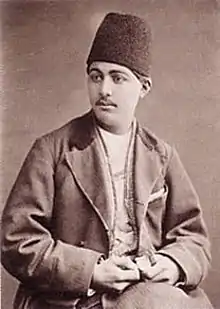

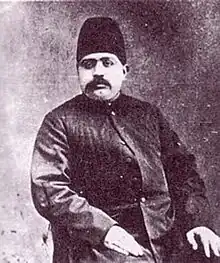

Amanollah Khan Zia' os-Soltan (also Amanollah Khan Donboli "Nazer ol-Ayaleh" "Zia' os-Soltan") was an Iranian aristocrat and politician at Qajar court during the time of Mozaffar ad-Din Shah, Mohammad Ali Shah and Ahmad Shah Qajar and hero of the Persian Constitutional Revolution.

Family Background

Amanollah Khan was born 1863 at Tabriz, died on 11 February 1931 by cancer in Hamburg when on a visit to see medical specialists, and was buried there at the Iranian-Muslim department of Ohlsdorf Cemetery. He was the son of Safar Khan from the Donboli family, who ruled as hereditary Khans the cities of Tabriz and Khoy. A wealthy big landowner Amanollah Khan held possession of half the city of Tabriz and large landed properties at Alamdar in the Iranian province of Azerbaijan (Iran).

This was also the reason he was sometimes called Tabrizi (meaning "from Tabriz"), because family names were unknown in Iran of that time. Later Mozaffar ad-Din Shah gave him the noble title "Zia' os-Soltan" (lit. "Splendour of the Sovereign") for his merits in affairs of state, by which he became popular. Firstly he married in 1897 Princess Shazdeh Khanom Malekeh-Afagh Bahman-Qajar, granddaughter of Prince Bahman Mirza Qajar, by whom he got his two children, the Shahzadehs Nosrat ol-Molouk Khanom Bahman and Abol Qassem Bahman. After her death in 1917 he married secondly in 1923 a rich landlady from Damghan, Turkan Aqa Khanom but without any issue.[1]

Career

In the time when Crown Prince Mozaffar ad-Din Mirza was heir apparent of Persia and had his seat of power in Tabriz, Amanollah Khan held the administrative post of Nazer ol-Ayaleh (lit. "Warden of the Province"). When in 1896 the new shah proclaimed Mozaffar ad-Din Shah (r. 1896–1906) took up residence at Tehran, Amanollah Khan came with the so-called Turki-fraction from Tabriz to Tehran, arose at court to the imperial entourage and was awarded with the title of "Zia' os-Soltan" by the shah. With his marriage to a Qajar princess - a cousin to the shah - Zia' os-Soltan was close related to the Imperial house. The family lived in the 1903 newly electric illuminated Tehran district of Cheragh-Bargh (lit. "electric light"), at the Khiyaban-e Cheragh Bargh ("Avenue Electric Light"). Thus, some sources also gave Zia' os-Soltan the sobriquet Cheragh-Barghi (lit. "Coming from Tcheragh-Bargh").

As a liberal Qajar aristocratic, a man who stood up for the politics and democracy, he was delegate of Tabriz at the first Persian National Council to Tehran, when on 15 August 1906 Mozaffar ad-Din Shah proclaimed after the Constitutional Revolution (mashruteh) reforms and a parliament (majles). Zia' os-Soltan became a leader of the constitutional wing (ejtema'iyun) ready for democratic reforms. He was also one of those Qajars notables, who supported the constitution against efforts of Mohammad Ali Shah (r. 1906–1909) for returning to absolutism in 1908.[2]

When Mohammad Ali Shah came to power in 1906, he feared that the European powers, especially Britain, could strengthen their influence via the parliament. However, the shah rejected his father's democratic measures and, dissolving the First Majles, reclaimed absolute power. Finally, riots broke out in Tehran and Tabriz against the government and constitutional forces rose up in both cities. On 4 June 1909 Mohammad Ali Shah, fearing for his personal safety, left Golestan Palace for Bagh-e Shah (lit. "Royal Garden"), a residence just outside the city and later a village for the aristocracy, where he would be safe under the protection of the Cossack Brigade. When the people protested against his politics, the shah demanded the Cossacks for bombarding the parliament building Baharestan (lit. "Place of Springtime").

Then, a few days later, Zia' os-Soltan was arrested with some other political leaders and Qajar princes, too. He was accused of being involved in a bomb assault against the shah. The only food for each prisoner a day was one round bread and cucumbers. They were denied fresh cold water and thus they were forced to drink the dirty water of a small pool. Each day their guard, a certain Soltan Bagher, would take them out eight by eight in chains, and brought them to the tribunal of interrogators. These men supporting the shah's autocratic style to rule were Moayyed od-Dowleh (the Governor of Tehran), Prince Moayyed os-Saltaneh, Seyyed Mohsen Sadr ol-Ashraf, Mir Panj Arshad od-Dowleh, Mirza Abdol Motalleb Yazdi (the editor of the royalist Adamiyat newspaper) and Mirza Ahmad Khan (the writer of the police station). The tribunal was investigating three matters and by means of torture and pressure wanted to get information about: 1) Who had thrown the bomb at the Shah? 2) Who was the founder of the anjoman (Freemason lodge) in the house of Ali Reza Khan Qajar Amirsoleimani Azod ol-Molk (a Qajar elder and the tribal head or Ilkhan, who became later regent to the young Ahmad Shah, who was suspected in plotting against Mohammad Ali Shah and replacing him with his uncle Mass'oud Mirza Zell-e Soltan)? 3) Who was giving rifles to the mojaheds? Other than that they were not interested in the events of the Majles and the Mashruteh.[3]

In all this they would not spare the prisoners any torture or hurt with regard to some of them in particular, especially the editor of the Rouh ol-Qodos newspaper, Soltan ol-Olama Khorasani Rouh ol-Qodos, and Zia' os-Soltan. Because these two men were suspected that they had knowledge of the background to the attempt on the shah's life, they were subjected to severe torture. Every night they would be taken out and tied to stools and beaten severely and though their cries would resonate in the entire Bagh-e Shah, none of those Generals and Ministers present would come to their rescue.[4]

Finally before his execution Zia' os-Soltan was released with others accused of being guilty of the attempt on Mohammad Ali Shah's life, among them Heydar Amoghli, Esmail Ghafghazi, Mirza Mousa Khan Zargar and Reza Azarbeidjani, who had thrown the bomb. This happened when revolutionary troops, backed by the British, moved into Tehran in July 1909, took over the city and could free them. Three days later, Mohammad Ali Shah asked for asylum in the Russian embassy, was forced to abdicate and leave the country. In his place his twelve-year-old son, Soltan Ahmad Shah (r. 1909–1925), was made ruler under the supervision of a regent. Thus, in the next decade Mirza Amanollah Khan Zia' os-Soltan was a political advisor of the young shah's government.[5]

Last years

In 1923 Zia' os-Soltan was also one of those personalities consulted by Reza Khan Sardar-Sepah, who intended to form a government in the anticipated absence of Soltan Ahmad Shah. But later in 1925 Reza Khan finally declared himself monarch as Reza Shah Pahlavi and founded a new dynasty. Even in 1926 Zia‘ os-Soltan should have been nominated minister to Reza Shah's cabinet. At first he trusted in the democratic pretensions of the new shah and his ability to reform the country.

Thus, to show the close relations between his own family and the new dynasty, he presented a bowl made out of pure gold with his own signature inscribed as a gift to the shah (now you can see it among the other treasures in Tehran's National Jewel Museum at the Central Bank of Iran Bank-e Markazi). But later in 1926 Zia' os-Soltan rejected his appointment and was betrayed when he saw Reza Shah had become dictator and all of Iran's democratic achievements were made null. As well as it happened to several other Qajar nobles, Reza Shah Pahlavi occupied most of Zia' os-Soltan's possessions and estates in Azerbaijan and made them crown domains (i.e., his own domains). Up from this point Amanollah Khan did not care about any political questions further more but only about his Tehran residence at Khiyaban-e Ferdowsi in Bagh-e Shah and his real estate and last two large villages left by the Pahlavis, Alamdar, near Tabriz, and Mehmandust, between Semnan and Damghan at the Caspian coast.

There is another story run within his family: "One day Reza Shah visited Zia' os-Soltan at his residence in Bagh-e Shah. The monarch's eyes fall on a rosary (tasbih) of Zia os-Soltan fully made of fine rubies. This jewel pleased the shah so much that he asked him about it, what in fact was an order to Zia os-Soltan to give the shah that rosary as a gift."[6]

References

- ↑ Private Interview with Keywan Zarrinkafsch, Hamburg 2000.

- ↑ Ahmad Kasravi: Tarikh-e Mashruteh-ye Iran (History of the Constitutional Revolution in Iran), vol 1, Tehran, 2537 imperial calendar, p. 661.

- ↑ Soltan Ali Mirza Kadjar: "Mohammad Ali Shah: The King and the Man", in: Qajar Studies, 2009, p. 185.

- ↑ Ahmad Kasravi: Tarikh-e Mashruteh-ye Iran (History of the Constitutional Revolution in Iran), vol 1, Tehran, 2537 imperial calendar, p. 661

- ↑ Mehdi Bamdad, Rejal-e Iran

- ↑ Interview with Keywan Zarrinkafsch, 2000.