| American lion Temporal range: Pleistocene, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton from the La Brea tar pits at the George C. Page Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | †P. atrox |

| Binomial name | |

| †Panthera atrox | |

| |

| The maximal range of cave lions - red indicates Panthera spelaea, blue Panthera atrox, and green Panthera leo. | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Panthera atrox, better known as the American lion, also called the North American lion, or American cave lion, is an extinct pantherine cat. Panthera atrox lived in North America during the Pleistocene epoch, from around 340,000 to 12,800 years ago.[2][3][4][5] The species was initially described by American paleontologist Joseph Leidy in 1853 based on a fragmentary mandible (jawbone) from Mississippi; the species name ('atrox') means "savage" or "cruel". The status of the species is debated, with some mammalogists and paleontologists considering it a distinct species or a subspecies of Panthera leo, which contains living lions. However, novel genetic evidence has shown that it is instead a distinct species derived from the Eurasian cave or steppe lion (Panthera spelaea), evolving after its geographic isolation in North America. Its fossils have been excavated from Alaska to Mexico.[6][7] It was about 25% larger than the modern lion, making it one of the largest known felids.[8]

History and taxonomy

Initial discovery and North American fossils

The first specimen now assigned to Panthera atrox was collected in the 1830s by William Henry Huntington, Esq., who announced his discovery to the American Philosophical Society on April 1, 1836 and placed it with other fossils from Huntington's collection in the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia.[1] The specimen had been collected in ravines in Natchez, Mississippi that were dated to the Pleistocene; the specimen consisted only of a partial left mandible with 3 molars and a partial canine.[1] The fossils didn't get a proper description until 1853 when Joseph Leidy named the fragmentary specimen (ANSP 12546) Felis atrox ("savage cat").[1] Leidy named another species in 1873, Felis imperialis, based on a mandible fragment from Pleistocene gravels in Livermore Valley, California. F. imperialis however is considered a junior synonym of Panthera atrox.[7] A replica of the jaw of the first American lion specimen to be discovered can be seen in the hand of a statue of famous paleontologist Joseph Leidy, currently standing outside the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia.

Few additional discoveries came until 1907, when the American Museum of Natural History and College, Alaska collected several Panthera atrox skulls in a locality originally found in 1803 by gold miners in Kotzebue, Alaska.[9] The skulls were referred to a new subspecies of Felis (Panthera) atrox in 1930, Felis atrox "alaskensis". Despite this, the species didn’t get a proper description and is now seen as a nomen nudum synonymous with Panthera atrox.[7] Further south in Rancho La Brea, California, a large felid skull was excavated and later described in 1909 by John C. Merriam, who referred it to a new subspecies of Felis atrox, Felis atrox bebbi.[10][9] The subspecies is synonymous with Panthera atrox.[7]

Throughout the early to mid 1900s, dozens of fossils of Panthera atrox were excavated at La Brea, including many postcranial elements and associated skeletons.[10] The fossils were described by Merriam & Stock in detail in 1932, who synonymized many previously named taxa with Felis atrox.[9] At least 80 individuals are known from La Brea Tar Pits and the fossils define the subspecies, giving a comprehensive view of the taxon.[10] It wasn’t until 1941 that George Simpson moved Felis atrox to Panthera, believing that it was a subspecies of jaguar.[9] Simpson also referred several fossils from central Mexico,[11] even as far south as Chiapas, as well as Nebraska and other regions of the western US, to P. atrox.[9] 1971 witnessed the description of fragmentary remains from Alberta, Canada that extended P. atrox’s range north.[12][11] In 2009, an entrapment site at Natural Trap Cave, Wyoming was briefly described and is the second most productive Panthera atrox-bearing fossil site. It most importantly contains well-preserved mitochondrial DNA of many partial skeletons.

Panthera onca mesembrina and possible South American material

In the 1890s in the “Cueva del Milodon” in southern Chile, fossil collector Rodolfo Hauthal collected a fragmentary postcranial skeleton of a large felid that he sent to Santiago Roth who described them as a new genus and species of felid, "Iemish listai", in 1899,[13] though the name is considered a nomen nudum.[13] 5 years later in 1904, Roth reassessed the phylogenetic affinities of “Iemish” and named it Felis listai and referred several cranial and fragmentary postcranial elements to the taxon. Notably, several mandibles, a partial skull, and pieces of skin were some of the specimens referred.[13] 30 years later in 1934, Felis onca mesembrina was named by Angel Cabrera based on that partial skull from “Cueva del Milodon” and the other material from the site was referred to it.[13] Unfortunately, the skull (MLP 10-90) was lost, and was only illustrated by Cabrera.[13] Further material, including feces and mandibles, was referred to as F. onca mesembrina from Tierra del Fuego, Argentina and other southern sites in Chile.[14]

In 2016, the subspecies was referred to Panthera onca in a genetic study, which supported its identity as a subspecies of jaguar.[15] Later in 2017, the subspecies was synonymized with Panthera atrox based on morphological similarities of all material, although these similarities are unreliable.[13]

Evolution

The American lion was initially considered a distinct species of Pantherinae, and designated as Panthera atrox /ˈpænθərə ˈætrɒks/, which means "cruel" or "fearsome panther" in Latin. Some paleontologists accepted this view, but others considered it to be a type of lion closely related to the modern lion (Panthera leo) and its extinct relative, the Eurasian cave lion (Panthera leo spelaea or P. spelaea). It was later assigned as a subspecies of P. leo (P. leo atrox) rather than as a separate species.[3] Most recently, both spelaea and atrox have been treated as full species.[4]

Cladistic studies using morphological characteristics have been unable to resolve the phylogenetic position of the American lion. One study considered the American lion, along with the cave lion, to be most closely related to the tiger (Panthera tigris), citing a comparison of the skull; the braincase, in particular, appears to be especially similar to the braincase of a tiger.[16] Another study suggested that the American lion and the Eurasian cave lion were successive offshoots of a lineage leading to a clade which includes modern leopards and lions.[17] A more recent study comparing the skull and jaw of the American lion with other pantherines concluded that it was not a lion but a distinct species. It was proposed that it arose from pantherines that migrated to North America during the mid-Pleistocene and gave rise to American lions and jaguars (Panthera onca).[3] Another study grouped the American lion with P. leo and P. tigris, and ascribed morphological similarities to P. onca to convergent evolution, rather than phylogenetic affinity.[18]

Mitochondrial DNA sequence data from fossil remains suggests that the American lion (P. atrox) represents a sister lineage to the Eurasian cave lion (P. spelaea), and likely arose when an early cave lion population became isolated south of the North American continental ice sheet about 340,000 years ago.[19] The most recent common ancestor of the P. atrox lineage is estimated to have lived about 200,000 (118,000 to 346,000) years ago. This implies that it became genetically isolated from P. spelaea before the start of the Illinoian glaciation; a spelaea population is known to have been present in eastern Beringia by that time, where it persisted until at least ~13,290 cal. BP (11,925 ± 70 radiocarbon BP).[19] This separation was maintained during the interstadials of the Illinoian and following Wisconsin glaciations as well as during the Sangamonian interglacial between them. Boreal forests may have contributed to the separation during warmer intervals; alternatively, a reproductive barrier may have existed.[19]

The study also indicates that the modern lion is the closest living relative of P. atrox and P. spelaea.[19] The lineages leading to extant lions and atrox/spelaea were thought to have diverged about 1.9 million years ago,[4] before a whole genome-wide sequence of lions from Africa and Asia by Marc de Manuel et al. showed that the lineage of the cave lion diverged from that of the modern lion around 392,000 – 529,000 years ago.[20]

Description

The American lion is estimated to have measured 1.6 to 2.5 m (5 ft 3 in to 8 ft 2 in) from the tip of the nose to the base of the tail and stood 1.2 m (3.9 ft) at the shoulder.[21] Panthera atrox was at least as sexually dimorphic as African lions, with an approximate range of between 235kg to 523 kg (518lbs-1153lbs) in males and 175kg to 365 kg (385lbs-805lbs) for females.[22] In 2008, the American lion was estimated to weigh up to 420 kg (930 lb).[23][24] A study in 2009 showed an average weight of 256 kg (564 lb) for males and 351 kg (774 lb) for the largest specimen analyzed.[3]

Panthera atrox had limb bones more robust than those of an African lion, and comparable in robustness to the bones of a brown bear.[25]About 80 American lion individuals have been recovered from the La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles, so their morphology is well known.[26] Their features strongly resemble those of modern lions, but they were considerably larger, similar to P. spelaea and the Pleistocene Natodomeri lion of eastern Africa.[27]

Preserved skin remains found with skeletal material thought by its describers to be from the American lion in caves in the Argentine Patagonia indicate that the animal was reddish in color. Cave paintings from El Ceibo in the Santa Cruz Province of Argentina seem to confirm this, and reduce the possibility of confusion with fossil jaguars, as similar cave paintings accurately depict the jaguar as yellow in color.[28][14]

Distribution

The earliest lions known in the Americas south of Alaska are from the Sangamonian Stage – the last interglacial period – following which, the American lion spread from Alberta to Maryland, reaching as far south as Chiapas, Mexico.[11][29] It was generally not found in the same areas as the jaguar, which favored forests over open habitats.[21] It was absent from eastern Canada and the northeastern United States, perhaps due to the presence of dense boreal forests in the region.[30][31] The American lion was formerly believed to have colonized northwestern South America as part of the Great American Interchange.[32] However, the fossil remains found in the tar pits of Talara, Peru actually belong to an unusually large jaguar.[33][34][35] On the other hand, fossils of a large felid from late Pleistocene localities in southern Chile and Argentina traditionally identified as an extinct subspecies of jaguar, Panthera onca mesembrina, have been reported to be remains of the American lion.[13]

Habitat

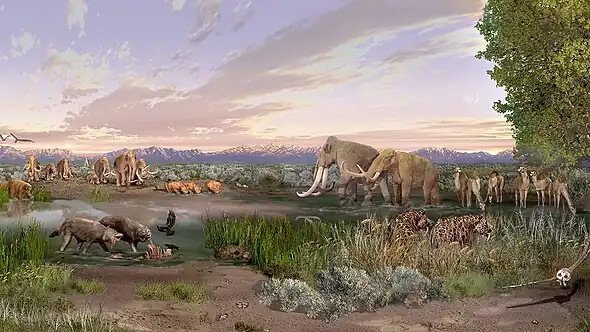

The American lion inhabited savannas and grasslands like the modern lion.[8] In some areas of their range, American lions lived under cold climatic conditions. They probably used caves for shelter from the cold weather in those areas,[31][note 1] and might have lined their dens with grass or leaves, as the modern Siberian tiger does.[31]

Paleoecology

American lions likely preyed on deer, horses, camels, tapirs, American bison, mammoths, and other large ungulates (hoofed mammals).[3][31] Evidence for predation of bison by American lions is particularly strong as a mummified carcass nicknamed "Blue Babe" was discovered in Alaska with clear bite and claw marks from lions. Based on the largely intact nature of the carcass, it probably froze before the lions could devour it.[36]

La Brea Tar Pits

The remains of American lions are not as abundant as those of other predators like Smilodon fatalis or dire wolves (Aenocyon dirus) at the La Brea Tar Pits, which suggests that they were better at evading entrapment, possibly due to greater intelligence.[8] While the ratio of recovered juveniles to adults suggests that Panthera atrox was social, its rarity suggests that it was at least more solitary than Smilodon and Aenocyon, or was social but lived in low densities.[37] Analyses of dental microwear suggest that the American lion actively avoided bone just like the modern cheetah (more so than Smilodon). Panthera atrox has the highest proportion of canine breakage in La Brea, suggesting a consistent preference for larger prey than contemporary carnivores. Dental microwear additionally suggests that carcass utilization slightly declined over time (~30,000 BP to 11,000 radiocarbon BP) in Panthera atrox.[22]

A gray wolf from the La Brea Tar Pits suffered a violent bite which amputated one of its lower right legs, although it apparently survived- researchers believe that Panthera atrox is a prime candidate for the injury, due to its bite force and bone shearing ability.[38]

Extinction

The American lion went extinct along with most of the Pleistocene megafauna during the Quaternary extinction event. The most recent fossil, from Edmonton, dates to ~12,877 cal. BP (11,355 ± 55 radiocarbon BP),[39][5] and is 400 years younger than the youngest cave lion in Alaska.[5] American lion bones have been found in the trash heaps of Paleolithic Americans, suggesting that human predation contributed to its extinction.[21][31]

See also

Notes

- ↑ This source confuses spelaea, which is the form found in Alaska and the Yukon, with atrox, the form known from Alberta southwards.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Leidy, Joseph (1853). "Description of an Extinct Species of American Lion: Felis atrox". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 10: 319–322. doi:10.2307/1005282. JSTOR 1005282.

- ↑ Harington, C. R. (1969). "Pleistocene remains of the lion-like cat (Panthera atrox) from the Yukon Territory and northern Alaska". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 6 (5): 1277–1288. Bibcode:1969CaJES...6.1277H. doi:10.1139/e69-127.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Christiansen, P.; Harris, J. M. (2009). "Craniomandibular morphology and phylogenetic affinities of Panthera atrox: implications for the evolution and paleobiology of the lion lineage". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 29 (3): 934–945. Bibcode:2009JVPal..29..934C. doi:10.1671/039.029.0314. S2CID 85975640.

- 1 2 3 Barnett, R.; Mendoza, M. L. Z.; Soares, A. E. R.; Ho, S. Y. W.; Zazula, G.; Yamaguchi, N.; Shapiro, B.; Kirillova, I. V.; Larson, G.; Gilbert, M. T. P. (2016). "Mitogenomics of the Extinct Cave Lion, Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810), Resolve its Position within the Panthera Cats". Open Quaternary. 2: 4. doi:10.5334/oq.24. hdl:10576/22920.

- 1 2 3 Stuart, Anthony J.; Lister, Adrian M. (April 2010). "Extinction chronology of the cave lion Panthera spelaea". Quaternary Science Reviews. 30 (17–18): 2329–2340. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2010.04.023.

- ↑ Whitmore Jr, F.C.; Foster, H. L. (1967). "Panthera atrox (Mammalia: Felidae) from central Alaska". Journal of Paleontology. 61 (1): 247–251. JSTOR 1301922.

- 1 2 3 4 Montellano-Ballesteros, M.; Carbot-Chanona, G. (2009). "Panthera leo atrox (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae) in Chiapas, Mexico". The Southwestern Naturalist. 54 (2): 217–223. doi:10.1894/CLG-20.1. S2CID 85346247.

- 1 2 3 Deméré, Tom. "SDNHM Fossil Field Guide: Panthera atrox". Archived from the original on 2009-06-25. Retrieved 2010-05-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Simpson, G. G. (1941). Large Pleistocene felines of North America. American Museum novitates; no. 1136.

- 1 2 3 Merriam, J. C., & Stock, C. (1932). The Felidae of Rancho La Brea (No. 422, p. 92). Carnegie Institution of Washington.

- 1 2 3 Marisol Montellano, Ballesteros; Carbot-Chanona, Gerardo (2009). "Panthera leo atrox (Mammalia: Carnivora: Felidae) in Chiapas, Mexico". The Southwestern Naturalist. 54 (2): 217–222. doi:10.1894/clg-20.1. S2CID 85346247.

- ↑ Harington, C. R. (1971). A Pleistocene lion-like cat (Panthera atrox) from Alberta. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 8(1), 170-174.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Chimento, Nicolás R.; Agnolin, Federico L. (2017-11-01). "The fossil American lion (Panthera atrox) in South America: Palaeobiogeographical implications". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 16 (8): 850–864. Bibcode:2017CRPal..16..850C. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2017.06.009. ISSN 1631-0683.

- 1 2 Chimento, N. R.; Agnolin, F. L. (2017). "The fossil American lion (Panthera atrox) in South America: Palaeobiogeographical implications". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 16 (8): 850–864. Bibcode:2017CRPal..16..850C. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2017.06.009.

- ↑ Metcalf, Jessica L.; Turney, Chris; Barnett, Ross; Martin, Fabiana; Bray, Sarah C.; Vilstrup, Julia T.; Orlando, Ludovic; Salas-Gismondi, Rodolfo; Loponte, Daniel; Medina, Matías; De Nigris, Mariana (2016-06-03). "Synergistic roles of climate warming and human occupation in Patagonian megafaunal extinctions during the Last Deglaciation". Science Advances. 2 (6): e1501682. Bibcode:2016SciA....2E1682M. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1501682. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 4928889. PMID 27386563.

- ↑ Groiss, J. Th. (1996). "Der Höhlentiger Panthera tigris spelaea (Goldfuss)". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie. 7: 399–414. doi:10.1127/njgpm/1996/1996/399.

- ↑ Christiansen, Per (2008-08-27). "Phylogeny of the great cats (Felidae: Pantherinae), and the influence of fossil taxa and missing characters". Cladistics. 24 (6): 977–992. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2008.00226.x. PMID 34892880. S2CID 84497516.

- ↑ King, L. M.; Wallace, S. C. (2014-01-30). "Phylogenetics of Panthera, including Panthera atrox, based on craniodental characters". Historical Biology. 26 (6): 827 833. Bibcode:2014HBio...26..827K. doi:10.1080/08912963.2013.861462. S2CID 84229141.

- 1 2 3 4 Barnett, R.; Shapiro, B.; Barnes, I. A. N.; Ho, S. Y. W.; Burger, J.; Yamaguchi, N.; Higham, T. F. G.; Wheeler, H. T.; Rosendahl, W.; Sher, A. V.; Sotnikova, M.; Kuznetsova, T.; Baryshnikov, G. F.; Martin, L. D.; Harington, C. R.; Burns, J. A.; Cooper, A. (2009). "Phylogeography of lions (Panthera leo ssp.) reveals three distinct taxa and a late Pleistocene reduction in genetic diversity". Molecular Ecology. 18 (8): 1668–1677. Bibcode:2009MolEc..18.1668B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04134.x. PMID 19302360. S2CID 46716748.

- ↑ Manuel, M. d.; Ross, B.; Sandoval-Velasco, M.; Yamaguchi, N.; Vieira, F. G.; Mendoza, M. L. Z.; Liu, S.; Martin, M. D.; Sinding, M.-H. S.; Mak, S. S. T.; Carøe, C.; Liu, S.; Guo, C.; Zheng, J.; Zazula, G.; Baryshnikov, G.; Eizirik, E.; Koepfli, K.-P.; Johnson, W. E.; Antunes, A.; Sicheritz-Ponten, T.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Larson, G.; Yang, H.; O’Brien, S. J.; Hansen, A. J.; Zhang, G.; Marques-Bonet, T.; Gilbert, M. T. P. (2020). "The evolutionary history of extinct and living lions". PNAS. 117 (20): 10927–10934. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11710927D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1919423117. PMC 7245068. PMID 32366643.

- 1 2 3 Anderson, Elaine (1984), "Who's Who in the Pleistocene: A Mammalian Bestiary", in Martin, P. S.; Klein, R. G. (eds.), Quaternary Extinctions, The University of Arizona Press, ISBN 978-0-8165-1100-6

- 1 2 DeSantis, Larisa R. G.; Schubert, Blaine W.; Scott, Jessica R.; Ungar, Peter S. (2012-12-26). "Implications of Diet for the Extinction of Saber-Toothed Cats and American Lions". PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e52453. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...752453D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052453. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3530457. PMID 23300674.

- ↑ Sorkin, B. (2008-04-10). "A biomechanical constraint on body mass in terrestrial mammalian predators". Lethaia. 41 (4): 333–347. Bibcode:2008Letha..41..333S. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.2007.00091.x.

- ↑ Merriam, J. C. & Stock, C. 1932: The Felidae of Rancho La Brea. Carnegie Institution of Washington Publications 442, 1–231.

- ↑ Anyonge, William (1996). "Locomotor behaviour in Plio-Pleistocene sabre-tooth cats: a biomechanical analysis". Journal of Zoology. 238 (3): 395–413. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1996.tb05402.x. ISSN 0952-8369.

- ↑ "About Rancho La Brea Mammals". Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. 2012-08-06. Archived from the original on 2017-10-28. Retrieved 2017-10-28.

- ↑ Manthi, F.K.; Brown, F.H.; Plavcan, M.J.; Werdelin, L. (2017). "Gigantic lion, Panthera leo, from the Pleistocene of Natodomeri, eastern Africa". Journal of Paleontology. 92 (2): 305–312. doi:10.1017/jpa.2017.68.

- ↑ "Revelan que el León Americano Habitó la Patagonia" [They Reveal that the American Lion Inhabited Patagonia]. Todo Ciencia (in Spanish).

- ↑ Harington, C. R. (1971-01-01). "A Pleistocene Lion-like Cat ( Panthera atrox ) from Alberta". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 8 (1): 170–174. Bibcode:1971CaJES...8..170H. doi:10.1139/e71-014. ISSN 0008-4077.

- ↑ "Panthera leo atrox". Paleobiology Database. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Harrington, C. R. (March 1996). "American Lion" (PDF). Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-30. Retrieved 2017-10-30.

- ↑ Kurtén, B.; Anderson, E. (1980). Pleistocene Mammals of North America. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231037334. OCLC 759120597.

- ↑ Seymour, Kevin L. (1983). The Felinae (Mammalia: Felidae) from the Late Pleistocene tar seeps at Talara, Peru, with a critical examination of the fossil and recent felines of North and South America (MSc thesis). University of Toronto.

- ↑ Seymour, Kevin L. (2015). "Perusing Talara: Overview of the Late Pleistocene fossils from the tar seeps of Peru" (PDF). Science Series. 42: 97–109. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-01. Retrieved 2015-12-23.

- ↑ Yamaguchi, N.; Cooper, A.; Werdelin, L.; MacDonald, D. W. (2004). "Evolution of the mane and group-living in the lion (Panthera leo): A review". Journal of Zoology. 263 (4): 329. doi:10.1017/S0952836904005242.

- ↑ Turner, Alan; Anton, Mauricio (1997). The Big Cats and Their Fossil Relatives.

- ↑ Carbone, Chris; Maddox, Tom; Funston, Paul J.; Mills, Michael G.L.; Grether, Gregory F.; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire (2009-02-23). "Parallels between playbacks and Pleistocene tar seeps suggest sociality in an extinct sabretooth cat, Smilodon". Biology Letters. 5 (1): 81–85. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0526. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 2657756. PMID 18957359.

- ↑ Scott, Eric; Rega, Elizabeth; Scott, Kim; Bennett, Bryan; Sumida, Stuart (September 15, 2015). Harris, John M. (ed.). "A Pathological Timber Wolf (Canis lupus) Femur from Rancho La Brea Indicates Extended Survival After Traumatic Amputation Injury" (PDF). La Brea and Beyond: The Paleontology of Asphalt-Preserved Biotas. Science Series 42: 33–36. ISBN 978-1-891276-27-9 – via Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

- ↑ Barnett, Ross; Shapiro, Beth; Barnes, Ian; Ho, Simon Y. W.; Burger, Joachim; Yamaguchi, Nobuyuki; Higham, Thomas F. G.; Wheeler, H. Todd; Rosendahl, Wilfried; Sher, Andrei V.; Sotnikova, Marina; Kuznetsova, Tatiana; Baryshnikov, Gennady F.; Martin, Larry D.; Harington, C. Richard (April 2009). "Phylogeography of lions ( Panthera leo ssp.) reveals three distinct taxa and a late Pleistocene reduction in genetic diversity". Molecular Ecology. 18 (8): 1668–1677. Bibcode:2009MolEc..18.1668B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04134.x. ISSN 0962-1083. PMID 19302360. S2CID 46716748.