_msu2017-9541.jpg.webp)

The Amphitheatre of Catania is a Roman amphitheatre in Catania, Sicily, Southern Italy, built in the Roman Imperial period, probably in the 2nd century AD, on the northern edge of the ancient city at the base of the Montevergine hill. Only a small section of the structure is now visible, below ground level, to the north of Piazza Stesicoro. This area is now the historic centre of the city, but was then on the outskirts of the ancient town and also occupied by the necropolis of Catania. The structure is part of the Parco archeologico greco-romano di Catania.

Description

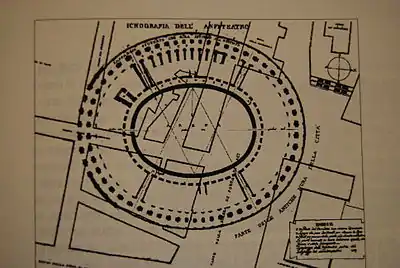

The amphitheatre of Catania is the most complicated and largest of all the amphitheatres in Sicily. It is one of a group of large arenas, which also includes the Colosseum, the Amphitheatre of Capua, and the Verona Arena. The structure centred on an elliptical arena, surrounded by radial walls and vaults supporting the seating of the cavea, which had 14 steps and 32 aisles. A gallery ran around the outside of the structure, on which the external facade is mounted. The arena had a maximum diameter of 70 metres and a minor diameter of around 50 metres, with a circumference of 192 metres. The external diameter was 125 x 105 metres, while the external circumference was 309 metres. Opus vittatum was used for the construction of the interior and opus quadratum for the exterior. The remains of the pilasters are in opus quadratum with small blocks of igneous rock. The cavea was made of basalt from Mount Etna, faced with marble. The external walls indicate a degree of carelessness in construction. The blocks are cut irregularly and seem to mostly have been recycled. The external arches are made with large rectangular bricks of regular shape and good quality mortar, while the internal ones are made of concrete, with large radial plates.

Despite the overall sobriety of the building, the contrast between the colour of the very dark igneous rock of the walls and the red bricks of the arches must have been very striking. A note of class was added by the employment of marble, not only for the cladding of the podium, but also for some decorations, such as the herms on the sides of the main entrance. The main stairs were probably made of limestone, creating a strong interplay with the white of the seating and the black of the other stairways. A cover with large awnings to protect people from strong sun and rain probably existed.

From the theatre's dimensions it can be calculated to have held 15,000 spectators and almost double that number with the addition of wooden bleachers for standing spectators.[1] According to an uncertain and unconfirmed tradition, it was intended that naumachiae (staged sea battles) take place in the amphitheatre, using the ancient Roman aqueduct of Catania to fill the arena with water.[2]

Entrance

The excavated part of the amphitheatre is now accessed by an ironwork gate. In 1906 the gate was decorated with some fragments of marble columns which were originally part of the upper loggia, two fragmentary Ionic columns, and part of an architrave inscribed with AMPHITHEATRVM INSIGNE ("Eminent Amphitheatre"). The iron gate is at the centre, between the columns which have capitals, which support the architrave. The other two columns are located on either side, with stone walls in between with symbolic epitaphs of two illustrious ancient Greeks linked to this area (Charondas on the left and Stesichorus on the right), which were composed by the poet Mario Rapisardi. Tradition has it that their tombs are actually in the area of the amphitheatre.

History

The monument was probably built in the 2nd century AD. The exact date is uncertain, but the architectural style suggests some time between the Emperors Hadrian and Antoninus Pius. It seems clear that it was expanded in the 3rd century AD, tripling the structure's size.[3]

A baseless popular legend claims that lava flows from the eruption of Etna in 252 reached the theatre but did not destroy it. This tradition derives from the life of Saint Agatha as reported in the Acta Sanctorum of Jean Bolland, where it is reported that in the specific year of the saint's death (251) lava flowed towards the gates of the city and the farmers, worried for their fields, went to the tomb of the saint, removed her funerary shroud and used it to stop the lava. Although this source is obviously hagiographical, it led vulcanologists like Carlo Gemmellaro to erroneously interpret the amphitheatre (which is near the city gates) as the point where the lava stopped. Recent stratigraphic studies have clearly shown that the rock identified as the 'lava flow of Saint Agatha' of 252 actually came from Monpeloso and flowed through the area of Nicolosi before cooling and solidifying in Mascalucia, about 450 metres above sea level. Thus, it moved toward Catania but never actually reached it.[4] The sole traces of lava near the amphitheatre are a lava ledge which abuts one of the vaulted walls of the building. However, when a core was drilled into the walls of the internal walkway in the twentieth century in order to determine what was behind them, "wagonloads" of liquid flowed out,[3] clearly indicating that the space behind is empty. The fragment of volcanic rock is very likely fill placed there in order to support the foundations of the facade of the Chiesa di San Biagio above it.

According to Cassiodorus, in the 5th century, Theodoric, King of the Ostrogoths, allowed the inhabitants of the city to spoliate the theatre for building material for the construction of stone buildings,[5][6] on the grounds that the monument had been abandoned "for a long time."[5] According to some authors, Roger II further spoliated the structure in the 11th century for the construction of Catania Cathedral, including the grey granite columns that decorate the cathedral's facade and the apses,[7] in which perfectly cut stones can be seen,[8] which may also have been used in the construction of the Castello Ursino in the Swabian period.

In the 13th century, according to tradition, the amphitheatre's vomitoria (entranceways) were used by the Angevins to enter the city during the Sicilian Vespers. In the following century, the entrances were walled up and the ruins were incorporated into the Aragonese fortifications (1302). In 1505, the civic senate granted Giovanni Gioeni a concession to use the monument's stone for the construction of houses and to use the arena itself as a garden.[8] Measures were taken to secure the ruins in the construction of new fortifications in 1550: the first and second stories were knocked down and the galleries were filled in with the rubble. After the 1693 Sicily earthquake, it was finally buried, and the area was turned into a parade ground. Subsequently, the extrados of the galleries were used as the foundations of new houses and for the Neo-classical facade of the Church of San Biagio.

From the second half of the 18th century, the amphitheatre was the object of archaeological excavation. However the discoveries were not preserved: instead the arches were walled up and reused in the buildings of the reconstructed city. In the early years of the 20th century, renovation work was undertaken in order to open the site to visitors, as part of the construction of the Piazza Stesicoro. In 1943, during the allied bombardment which reduced parts of the city to rubble, the structure was used as a bomb shelter. Subsequently, it experienced periods of interest and abandonment. For several years, the tunnels were kept shut for 'security reasons', following tragic accidents resulting from people exploring. The amphitheatre was renovated in 1997 and opened that summer. Then it was closed due to the influx of sewerage from the neighbouring houses. This was partially fixed and it was reopened to the public in 1999, but then closed a little later as a result of its deterioration.

The remains, representing about a tenth of the amphitheatre, are visible from the entrance of the Piazza Stesicoro and from the Vico Anfiteatro, where the structure is visible up to the third floor. Until 2007, it was possible to see part of second story on the Via del Colosseo, but it is now entirely covered by the new terrace of the Villa Cerami. Inside the villa, which is now used by the University of Catania's Faculty of jurisprudence, it is still possible to see part of the vaulting system that linked the Amphitheatre to the Montevergine hill (probably the ancient acropolis of the city). The rest of the amphitheatre is below the Via Neve, Via Manzoni, and Via Penninello.

The early modern excavations seem to be the reason for the instability of the structure, which was announced in 2014 to be in danger of collapse in a parliamentary debate and which had already been brought to public attention by CTzen.[9] On 24 April 2014, an expert board was established in order to organise the recuperation of the monument and to safeguard the neighbourhood which has developed on top of the structure over the centuries.[10]

Research

The first modern scholar to discuss the amphitheatre at Catania was Tommaso Fazello, who also established its dimensions. Subsequently, fantastical reconstructions of structure were proposed by authors like Ottavio D'Arcangelo and Giovanni Battista Grossi, which did however include the first surveys of the building.

In the 18th century, Ignazio Paternò Castello expended substantial amounts of his own money on excavations, in order to establish beyond doubt that the amphitheatre had actually existed - a point that some visitors had strongly denied. Over a two-year period, he uncovered a whole corridor and four large arches of the external gallery.[11] In the 19th century, these excavations could still be accessed from an entrance on the Via del Colosseo (which was and is popular known as 'Catania Vecchia') and all kinds of legends have become associated with it, such as the tale of a school group which snuck into the structure for a visit and never came out.

In 1904, during the administration of Mayor Giuseppe De Felice Giuffrida, work began to bring the whole structure to light, under the supervision of the architect Filadelfo Fichera. This project ended two years later. At this time, a broad and mysterious landing passage was discovered,[12] probably a late extension of the building, which prevented those sat nearest to the arena from seeing the spectacles well and reduced the dimensions of the arena, but allowed a better view for an additional level, probably that added in the course of the 3rd century AD. In 1907, the opening ceremony was held, attended by king Victor Emmanuel III. Already by the Interwar period, the amphitheatre had been allowed to decay once more, to the extent that many of the buildings above were using the seating for sewerage.

In recent years, the amphitheatre has also been suddenly closed and reopened. At the end of 2007 and 2008, technical works were undertaken to determine the state of conservation of the external pilasters. On this occasion, it was possible to confirm that the structure had been renovated and expanded in a second phase. A subsequent investigation was then carried out which has been able to produce a virtual reconstruction of the structure.

See also

References

- ↑ For the measurements: R. J. Wilson, "La topografia della Catania romana. Problemi e prospettive," in Catania antica. Atti del Convegno della SISAC, Pisa-Roma 1996, pp. 165-167.

- ↑ S. Lagona, "L'acquedotto romano di Catania," in Cronache di archeologia e di storia dell'arte, 3, 1964.

- 1 2 Claudia Campese, Salvo Catalano (23 April 2014). "L'anfiteatro romano è a rischio collasso "Tra le cause c'è il giardino di villa Cerami"". MeridioNews (in Italian). Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ↑ Branca, p. 112

- 1 2 Cited in Garruccio 1854, p. 27

- ↑ R. Soraci, "Catania in età tardoantica," Quaderni catanesi di Cultura classica e medioevale 3, 1991, pp. 269-270

- ↑ Garruccio 1854, p. 29, n. b

- 1 2 Ferrara 1829, p. 294

- ↑ Bertorotta (M5S): "Salviamo l'anfiteatro romano di Catania" - YouTube

- ↑ Salvo Catalano (7 May 2014). "Anfiteatro, tavolo tecnico per correre ai ripari Un progetto per attingere ai fondi europei". MeridioNews (in Italian). Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ↑ Ignazio Paternò Castello, Viaggio per tutte le antichità della Sicilia. 2nd edition. Palermo, 1817 pp. 28-29.

- ↑ See e.g. G. Libertini in note in Adolf Holm, Catania Antica, Catania 1925, p. 39.

Sources

- Ignazio Paternò Castello, Viaggio per tutte le antichità della Sicilia, seconda edizione, postuma, Palermo 1817.

- Cesare Sposito, L'anfiteatro romano di Catania, Dario Flaccovio Editore, 2003.

- Francesco Giordano, L'Anfiteatro romano di Catania, Boemi Editore, Catania 2002.

- Maria Teresa Di Blasi, Il Cicerone. Storia, itinerari, leggende di Catania, seconda edizione, Edizioni Greco, Catania, 2007.

- Tino Giuffrida,Catania dalle origini alla dominazione normanna, Libreria Editrice Bonaccorso, Catania.

- Pinella Leocata, "Riapre l'anfiteatro romano," La Sicilia, 10 July 1999, CT31.

- AA.VV., Catania antica. Atti del Convegno della SISAC, Pisa-Roma 1996.

- Garruccio, Giovanni (1854). "Sulla origine e sulla costruzione dell'Anfiteatro di Catania, p. 27". Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- Ferrara, Francesco (1829). "Storia di Catania sino alla fine del secolo XVIII, pp 292-298". Catania. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- Branca, Tanguy. "Carta geologica del vulcano Etna. L'attività eruttiva dell'Etna negli ultimi 2700 anni, p. 112" (PDF). Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- Fabrizio Nicoletti (ed.), Catania Antica. Nuove prospettive di ricerca, Regione Siciliana, Palermo 2015.

External links

- "Il Filo di Arianna. Anfiteatro, Catania 1997". Archived from the original on 2010-09-26. Retrieved 2018-02-01.

- "Restituzione tridimensionale del monumento".