| Norrie disease | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Norrie disease is a rare disease and genetic disorder that primarily affects the eyes and almost always leads to blindness. It is caused by mutations in the Norrin cystine knot growth factor (NDP) gene, which is located on the X chromosome.[1][2] In addition to the congenital ocular symptoms, the majority of patients experience a progressive hearing loss starting mostly in their 2nd decade of life, and some may have learning difficulties among other additional characteristics.

Patients with Norrie disease may develop cataracts, leukocoria (where the pupils appear white when light is shone on them), along with other developmental issues in the eye, such as shrinking of the globe and the wasting away of the iris.[2] Around 30 to 50% of them will also have developmental delay or learning difficulties, psychotic-like features, incoordination of movements or behavioral abnormalities.[2] Most patients are born with normal hearing; however, the onset of hearing loss is very common in early adolescence.[3] About 15% of patients are estimated to develop all the features of the disease.[4]

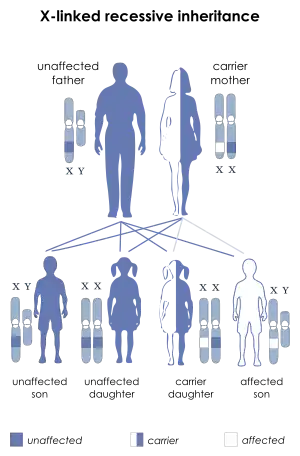

Due to the X-linked recessive pattern of inheritance, Norrie disease affects almost entirely males. Only in very rare cases, females have been diagnosed with Norrie disease; cases of symptomatic female carriers have been reported.[5][6] It is a very rare disorder that is not associated with any specific ethnic or racial groups, with cases reported worldwide (including cases in North America, South America, Europe, Asia and Australasia).[7][8][9][10] While more than 400 cases have been described, the prevalence and incidence of the disease still remains unknown.[11][12]

Presentation

The most prominent symptoms initially observed in Norrie disease are ocular. Initial characteristics are usually identified at birth or in early infancy, with parents often noticing abnormal eye features or that their child fails to show a response to light.[13][14][15] The first visible finding is leukocoria, a grayish-yellow pupillary reflection that originates from a mass of disorganized tissue behind the lens. This material, which possibly includes an already detached retina, may be confused with a tumor and thus is termed pseudoglioma.[2][11] However, an affected baby may have a normally sized eye globe and unremarkable iris, anterior chamber, cornea and intraocular pressure. Over the first few months of life, complete or partial retinal detachment evolves. From infancy through childhood, the patient may undergo progressive changes in the disease.[2] Disease progression often includes vitreoretinal hemorrhages, the formation of cataracts, deterioration of the iris with adhesions forming between the iris and the lens or the cornea, and shallowing of the anterior chamber which may increase intraocular pressure, causing eye pain.[2] As the situation worsens, there is corneal opacification, where the cornea becomes opaque, and band keratopathy. Intraocular pressure is lost and the globe shrinks. In the last stage of Norrie disease, the globes appear small and sunken in (phthisis bulbi) and the cornea appears to be milky.[2]

Auditory symptoms are common with Norrie disease. Progressive hearing loss has been reported to occur in 85–90% of patients and onset is generally in childhood and before the patient reaches their mid-20s.[7][16] Early hearing loss is sensorineural, mild and asymmetric.[2] By adolescence, high-frequency hearing loss begins to appear. Hearing loss is severe, symmetric, and broad-spectrum by the age of 35 years. However, studies show that while hearing deteriorates, the ability to speak well is highly preserved.[3] The slowly progressing hearing loss is more problematic to adjust to than the congenital blindness for most people with Norrie disease.[2]

Additional characteristics

Individuals with Norrie disease can also have cognitive and behavioral symptoms. Developmental delay or learning difficulties are present in about 30 to 50% of males who have Norrie disease.[2] Psycho-social disturbances and poorly characterized behavior abnormalities may also be present. In a study reporting extraocular manifestations in 56 patients with Norrie disease, conditions reported included cognitive impairment (28% of patients), behavioral issues, for example autism spectrum disorder (27% of patients presented with autism or autism-like disorders), neurological features, including seizure disorders and epilepsy (16% of patients reported seizures or seizure history), and peripheral vascular disease (38% of patients).[7]

Additionally, children with visual impairment have been shown to struggle establishing regular sleep/wake cycles due to reduced light perception impacting on their understanding of night and day; this can impact on the individual's behavior, mood and cognitive ability.[17] Consistent with this, some case reports of Norrie disease patients have reported the presence of sleep disorders.[18]

Peripheral vascular disease (PVD) has also been associated with Norrie disease. In a study of 56 patients with Norrie disease, 21 patients (38%) reported PVD (including varicose veins, peripheral venous stasis ulcers and erectile dysfunction).[7] Due to the known role of the protein norrin in the vascular development of the eye and inner ear, as well as the association with PVD, norrin is thought to have an important angiogenic role in the body.[19]

Genetics

Norrie disease is a rare genetic disorder caused by mutations in the NDP gene, located on Xp11.4 (GeneID: 4693).[20] It is inherited in an X-linked recessive manner. This means that almost only males are affected. Sons of affected men will not have the mutation, while all of their daughters will be genetic carriers of the mutation. Female carriers usually show no clinical symptoms, but will pass the mutation to 50% of their offspring. Daughters with the mutated gene will also be, like their mother, asymptomatic carriers, but 50% of their sons will express clinical symptoms.

Females are very unlikely to express clinical signs. However, there have been a few rare cases where females have shown symptoms associated with Norrie disease such as retinal abnormalities and mild hearing loss.[11] Additionally, cases of symptomatic female carriers have been reported.[5][6] One possible scenario that could lead to a female case of Norrie disease is if both of their copies of the NDP gene bear mutations, which could be the case in consanguineous families or due to a spontaneous somatic mutation. Another explanation for affected females could be skewed X-chromosome inactivation. In this latter case, carrier females with one mutated NDP allele could have a higher proportion of defective norrin being expressed, leading to the presentation of symptoms of Norrie disease.[5][6]

The NDP gene

Norrie disease is caused by a mutation in the Norrin cystine knot growth factor gene, also known as the Norrie disease (pseudoglioma) gene or NDP gene. Mutations could include splicing or mis-sense mutations, as well as partial or full gene deletion.[2] The normal function of the NDP gene is to produce the instructions for creating a protein called norrin. For the normal development of the eye and other body systems, norrin is believed to be crucial.[21] Norrin also appears to be crucial in the specialization of the cells of the retina and the establishment of a blood supply to the inner ear and the tissues of the retina. The role of norrin in the specialization of retinal cells for their unique sensory function is impeded by the mutation of NDP.[21] This results in an accumulation of immature retinal cells in the back of the eye. When norrin's role in the establishment of blood vessels supplying the eye is disrupted, the tissues cannot develop properly.[21]

Norrin is not only important in the development of the eye. The mutation of the NDP gene can affect other systems of the body as well. The most severe problems are caused by chromosomal deletions in the region of the NDP gene, causing the prevention of the gene product, or even that of the neighboring MAO genes. When the mutations simply change a single amino acid in norrin, the effects are less widespread and severe. However, the location and type of the NDP mutation does not necessarily determine the degree of severity of the disease, since highly varying clinical signs have been diagnosed in patients carrying exactly the same mutation. Therefore, the involvement of other modifying genes is very likely. On the other hand, if certain structurally important amino acids are changed (e.g. the cysteines forming the putative cystine knot), the clinical outcome has been shown to be more serious.[22]

Diagnosis

Norrie disease and other NDP related diseases are diagnosed with the combination of clinical findings and molecular genetic testing. Molecular genetic testing identifies the mutations that cause the disease in about 95% of affected males.[2] Clinical diagnoses rely on ocular findings. Norrie disease is diagnosed when grayish-yellow fibrovascular masses are found behind the eye from birth through three months. Doctors also look for progression of the disease from three months through 8–10 years of age. Some of these progressions include cataracts, iris atrophy, shallowing of anterior chamber, and shrinking of the globe.[2] Children with the condition either have only light perception or no vision at all.

In addition to its use for initial diagnosis, molecular genetic testing is used to confirm diagnostic testing (such as diagnosis by ocular examination), for carrier testing females, prenatal diagnosis, and preimplantation genetic diagnosis. There are three types of clinical molecular genetic testing. In approximately 95% of males, mis-sense and splice mutations of the NDP gene and partial or whole gene deletions are detected using sequence analysis.[2] Deletion/duplication analysis can be used to detect the 15% of mutations that are submicroscopic deletions. This is also used when testing for carrier females. The last testing used is linkage analysis, which is used when the first two types are unavailable. Linkage analysis is also recommended for those families who have more than one member affected by the disease.[2]

MRI is often used to diagnose the retinal dysplasia that occurs with the Norrie disease. However, the retinal dysplasia can be indistinguishable on MRI from persistent fetal vasculature, or the dysplasia of trisomy 13 and Walker–Warburg syndrome.[23]

For families with an existing history of Norrie disease, genetic counselling and in utero diagnosis of Norrie disease may be considered.[24] In utero diagnosis has been reported to include genetic testing by amniocentesis and ultrasonography to examine fetal eyes. Confirmation of diagnosis on the first day of life by ophthalmological examination under anesthesia has also been reported in some cases.[24][25]

Management

Ocular, auditory and behavioral management are the most common areas of intervention and treatment for patients with Norrie disease. For ocular (eye) management, often patients already have complete retinal detachment at birth, or by the time of diagnosis, so surgical intervention is often not offered. However, there is some evidence for the benefit of early surgery or laser therapy for cases where retinal detachment is incomplete.[2][25][26] Surgery may also be used to treat increased intraocular pressure and in rare cases enucleation (removal) of the eye is considered to control pain.[2]

A high proportion (85–90%) of individuals with Norrie disease experience progressive hearing loss in their second decade of life. In most cases, use of hearing aids has been shown to be effective into middle or late adulthood. For more significantly impaired hearing, cochlear implants may also be considered.[2][7][16]

30-50% of individuals with Norrie disease have been reported to present with developmental delay or cognitive impairment. Additionally, behavioral issues have also been reported. Supportive intervention and therapy, for example working with speech and language therapists and occupational therapists, can be used to maximize educational opportunities for these individuals.[2] Furthermore, training of teachers and school counselors on how to best support children with vision and hearing impairment can be extremely beneficial.

Routine monitoring of individuals with Norrie disease is recommended to best manage the disease. This includes regular follow-up with an ophthalmologist, even when vision is severely compromised. Additionally, due to the high proportion of individuals with Norrie disease who develop hearing loss, regular monitoring of hearing loss is beneficial to allow any hearing loss to be detected early and then correctly managed.[2] More recently, the use of dual sensory clinics has been proposed to provide improved care to patients living with conditions such as Norrie disease. For example, Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH), London are building a new Sight and Sound center, with the aim of improving the patient experience for individuals with conditions such as Norrie disease.[27] The benefits of dual sensory clinics include improved communication between the different health care professionals (HCPs) involved in management of Norrie disease (e.g. ophthalmologists and audiologists) as well as allowing more consistent training of staff on best practices for managing and interacting with individuals with sensory impairment.

Individuals with Norrie disease can often feel isolated from society due to difficulties in communication. In cases where hearing loss is also experienced, this psychological burden has been shown to increase. For example, a number of Norrie disease patients have been reported to experience transient depression correlating with the onset of hearing loss.[7] Because of this, the provision of emotional support to individuals with Norrie disease can be as important as clinical treatment strategies in terms of improving their quality of life and reducing disease burden.

Research

Research into understanding Norrie disease and how to improve the lives of those with Norrie disease is ongoing. For example, research is taking place at Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, University College London (UCL GOSICH) to study the developmental changes in the ear and eye in Norrie disease, with the hope to understand how to improve current treatment strategies.[28] The group at UCL GOSICH is focusing particularly on the hearing loss aspect of the disease, and whether it might be possible to treat by gene therapy.

History

In 1961, a Danish ophthalmologist named Mette Warburg reported on a Danish family that showed seven cases of a hereditary degenerative disease throughout seven generations. The first member of the family to be thoroughly studied was a 12-month-old boy. At the child's examination at three months, it was noticed that he was normal except that his lens appeared to be opaque and his irises were deteriorating.[29] The area behind his lens was filled with a growing yellowish mass. Five months later, his left eye was removed due to suspicion of retinoblastoma, a cancerous tumor on the retina. A histologic examination showed a hemorrhagic necrotic mass in the posterior chamber, surrounded by undifferentiated (immature, undeveloped) glial tissue. The diagnosis included a pseudotumor of the retina, hyperplasia of retinal, ciliary, and iris pigment epithelium, hypoplasia and necrosis of the inner layer of the retina, cataract, and phthisis bulbi. The physician had suspected a tumor, although it emerged that it was a developmental defect that led to the malformation of inner parts of the eye. Because the eye was not functional, cells had already begun to die (necrosis) and the eye globe began to shrink due to its dysfunction (phthisi bulbi). In this Danish family, five of the seven people in these cases developed deafness later in life. Also, in four of the seven, mental capacity was determined to be low. After Warburg researched literature under various medical categories, she discovered 48 similar cases which she believed were caused by this disease as well.[29] She then suggested this disease be named after another famous Danish ophthalmologist, Gordon Norrie (1855–1941). Norrie was greatly recognized for his work with the blind and for being a surgeon at the Danish Institute for the Blind for 35 years.[30] The NDP gene was previously named the “Norrie disease (pseudoglioma)” gene, which is still used widely when referring to NDP. However, the current approved name for NDP is “Norrin cystine knot growth factor”.[1]

Culture

There are two patient organizations for people affected by Norrie disease. The Norrie Disease Association (NDA) was founded in 1994 and is a US-based non-profit organization aiming to provide information and support to people living with Norrie disease and their families. The NDA holds a conference on Norrie disease every three years in Boston, US. The Norrie Disease Foundation (NDF) is a UK-based charity established in 2016. The main aims of NDF are to provide support for families and promote pioneering research into Norrie disease. They organize two family days a year where families with Norrie disease can come together to share experiences, meet each other and build relationships and supportive networks. The websites for both patient organizations contain useful information for patients and their families about the disease.

References

- 1 2 "Symbol Report for NDP". Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Sims K (1993). "NDP-Related Retinopathies – RETIRED CHAPTER, FOR HISTORICAL REFERENCE ONLY". NDP-Related Retinopathies. University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301506. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - 1 2 Halpin C, Owen G, Gutiérrez-Espeleta GA, Sims K, Rehm HL (July 2005). "Audiologic features of Norrie disease". The Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. 114 (7): 533–8. doi:10.1177/000348940511400707. hdl:10669/15119. PMID 16134349. S2CID 29284047.

- ↑ Dickinson JL, Sale MM, Passmore A, FitzGerald LM, Wheatley CM, Burdon KP, et al. (2006). "Mutations in the NDP gene: contribution to Norrie disease, familial exudative vitreoretinopathy and retinopathy of prematurity". Clinical & Experimental Ophthalmology. 34 (7): 682–8. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9071.2006.01314.x. PMID 16970763. S2CID 43683713.

- 1 2 3 Seller MJ, Pal K, Horsley S, Davies AF, Berry AC, Meredith R, McCartney AC (July 1995). "A fetus with an X;1 balanced reciprocal translocation and eye disease". Journal of Medical Genetics. 32 (7): 557–60. doi:10.1136/jmg.32.7.557. PMC 1050552. PMID 7562972.

- 1 2 3 Shastry BS, Hiraoka M, Trese DC, Trese MT (1999). "Norrie disease and exudative vitreoretinopathy in families with affected female carriers". European Journal of Ophthalmology. 9 (3): 238–42. doi:10.1177/112067219900900312. PMID 10544980. S2CID 37371789.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Smith SE, Mullen TE, Graham D, Sims KB, Rehm HL (August 2012). "Norrie disease: extraocular clinical manifestations in 56 patients". American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A. 158A (8): 1909–17. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.35469. PMID 22786811. S2CID 9397893.

- ↑ Chini V, Stambouli D, Nedelea FM, Filipescu GA, Mina D, Kambouris M, El-Shantil H (June 2014). "Utilization of gene mapping and candidate gene mutation screening for diagnosing clinically equivocal conditions: a Norrie disease case study". Eye Science. 29 (2): 104–7. PMID 26011961.

- ↑ Donnai D, Mountford RC, Read AP (February 1988). "Norrie disease resulting from a gene deletion: clinical features and DNA studies". Journal of Medical Genetics. 25 (2): 73–8. doi:10.1136/jmg.25.2.73. PMC 1015446. PMID 3162283.

- ↑ Halpin C, Sims K (November 2008). "Twenty years of audiology in a patient with Norrie disease". International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 72 (11): 1705–10. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2008.08.007. PMID 18817988.

- 1 2 3 "Norrie Disease". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- ↑ Sims K. "Norrie Disease". Retrieved 6 December 2019.

- ↑ Saini JS, Sharma A, Pillai P, Mohan K (1992). "Norries disease". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 40 (1): 24–6. PMID 1464451.

- ↑ Sukumaran K (March 1991). "Bilateral Norrie's disease in identical twins". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 75 (3): 179–80. doi:10.1136/bjo.75.3.179. PMC 1042303. PMID 2012789.

- ↑ Zhang XY, Jiang WY, Chen LM, Chen SQ (2013). "A novel Norrie disease pseudoglioma gene mutation, c.-1_2delAAT, responsible for Norrie disease in a Chinese family". International Journal of Ophthalmology. 6 (6): 739–43. doi:10.3980/j.issn.2222-3959.2013.06.01. PMC 3874509. PMID 24392318.

- 1 2 "Al-Yassin A, Norrie Disease Foundation, Unique. Unique and NDF Norrie Disease Information Leaflet" (PDF). 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-01-27. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- ↑ Stores G, Ramchandani P (May 1999). "Sleep disorders in visually impaired children". Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 41 (5): 348–52. doi:10.1017/S0012162299000766. PMID 10378763.

- ↑ Vossler DG, Wyler AR, Wilkus RJ, Gardner-Walker G, Vlcek BW (May 1996). "Cataplexy and monoamine oxidase deficiency in Norrie disease". Neurology. 46 (5): 1258–61. doi:10.1212/WNL.46.5.1258. PMID 8628463. S2CID 45839803.

- ↑ Michaelides M, Luthert PJ, Cooling R, Firth H, Moore AT (November 2004). "Norrie disease and peripheral venous insufficiency". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 88 (11): 1475. doi:10.1136/bjo.2004.042556. PMC 1772398. PMID 15489496.

- ↑ "NDP Norrie disease (pseudoglioma) [ Homo sapiens (human) ]". Gene. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Norrie disease (pseudoglioma)". Genetics Home Reference. U.S. National Library of Medicine. March 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- ↑ Meitinger T, Meindl A, Bork P, Rost B, Sander C, Haasemann M, Murken J (December 1993). "Molecular modelling of the Norrie disease protein predicts a cystine knot growth factor tertiary structure". Nature Genetics. 5 (4): 376–80. doi:10.1038/ng1293-376. PMID 8298646. S2CID 29858707.

- ↑ Castillo M (2011). Neuroradiology companion : methods, guidelines, and imaging fundamentals (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9781451111750.

- 1 2 Liu J, Zhu J, Yang J, Zhang X, Zhang Q, Zhao P (January 2019). "Prenatal diagnosis of familial exudative vitreoretinopathy and Norrie disease". Molecular Genetics & Genomic Medicine. 7 (1): e00503. doi:10.1002/mgg3.503. PMC 6382493. PMID 30474316.

- 1 2 Chow CC, Kiernan DF, Chau FY, Blair MP, Ticho BH, Galasso JM, Shapiro MJ (December 2010). "Laser photocoagulation at birth prevents blindness in Norrie's disease diagnosed using amniocentesis". Ophthalmology. 117 (12): 2402–6. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.03.057. PMID 20619898.

- ↑ Walsh MK, Drenser KA, Capone A, Trese MT (April 2010). "Early vitrectomy effective for Norrie disease". Archives of Ophthalmology. 128 (4): 456–60. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.403. PMID 20385941.

- ↑ "National Sensory Impairment Partnership. Calling UK Norrie families - Dual Sensory Clinics for children and young people up to 18 yrs". 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ↑ "Norrie Disease Foundation. Research". 2017-10-31. Archived from the original on 2020-01-27. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- 1 2 Warburg M (1961). "Norrie's disease: a new hereditary bilateral pseudotumour of the retina". Acta Ophthalmol. 39 (5): 757–772. doi:10.1111/j.1755-3768.1961.tb07740.x. S2CID 2525905.

- ↑ Gordon Norrie at Who Named It?. Retrieved 13 February 2007.