| Japanese eel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Anguilliformes |

| Family: | Anguillidae |

| Genus: | Anguilla |

| Species: | A. japonica |

| Binomial name | |

| Anguilla japonica | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The Japanese eel (Anguilla japonica; nihon unagi (日本鰻)[2]) is a species of anguillid eel found in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, China, and Vietnam,[3] as well as the northern Philippines. There are three main species under the Anguilla genus, and all three share very similar characteristics. These species are so similar that it is believed that they spawned from the same species and then experienced a separation due to different environments in the ocean. Like all the eels of the genus Anguilla and the family Anguillidae, it is catadromous, meaning it spawns in the sea but lives parts of its life in freshwater. Raised in aquaculture ponds in most countries, the Japanese eel makes up 95% of the commercially sold eel in Japan, the other 5% is shipped over by air to the country from Europe. This food in Japan is called unagi; they are an essential part of the food culture, with many restaurants serving grilled eel called kabayaki. However, presumably due to a combination of overfishing and habitat loss or changing water conditions in the ocean interfering with spawning and the transport of their leptocephali this species is endangered.[4]

Breeding

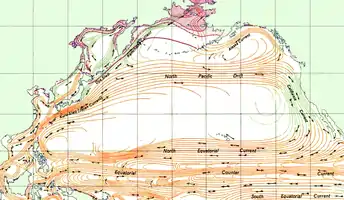

Between April and November, the Japanese eels leave their freshwater river habitats in East Asia to breed larvae in the ocean near the North Equatorial Current in the western North Pacific. Adult Japanese eels migrate thousands of kilometers from freshwater rivers in East Asia to their spawning area without feeding.[5] The eels are able to travel this long distance without nutrients because of the oils they collect in their bodies before the migration out to sea. The spawning area for this species is approximately 15°N, 140°E, a location corresponding with the location of a salinity front separating the north equatorial current from the tropical waters. This front is an indicator to tell the eels that they are in their preferred spawning location. The North Equatorial Current assists the eels in migrating from the center of the Pacific Ocean to the coast of Asia; without this indicator, the larvae would end up in the Mindanao Current.

The discovery of the Japanese eel breeding location was a new finding in 1991 when R.V. Hakuho Maru performed a research cruise. Before this research cruise, little was known about how eels breed, and there is still so much to learn as these eels remain a mystery to many scientists. Until the late 20th century, scientists hypothesized that the different stages of the eel's life cycle were entirely different species.Then in 2005, the same team of Japanese scientists at the University of Tokyo found a more precise location of spawning based on genetically identified specimens of newly hatched pre-larva only 2 to 5 days old in a small area near the Suruga Seamount to the west of the Mariana Islands (14–17° N, 142–143° E).[6]

The larvae, also known as leptocephalius, hatch from the egg approximately 36 hours after fertilization. These leptocephalius grow from 7.9 to 34.2 mm, growing by 0.56 mm daily. After riding the north equatorial current, the leptocephali take and head northward by the Kuroshio Current to east Asia. These eels live in rivers, lakes, and estuaries until they return to the ocean as adults to breed and die off.[7]

Life cycle

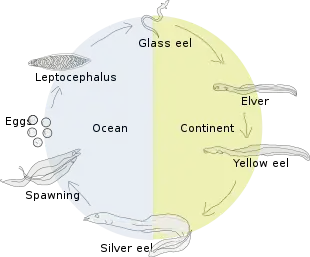

The Japanese eel metamorphoses into five stages throughout its life cycle, all with their distinct names. In the open ocean, leptocephalus, the first stage after the egg, feed on marine snow. Approximately 18 months after hatching, they metamorphose into "glass eels", a name derived from their clear appearance.

As these glass eels reach their freshwater habitats from December to April they become known as Elvers. The migration time of this species corresponds with the moon as it affects the tide. This time is during a tide that occurs at night and simulates a flood making it easier for the eels to survive their migration. An eel at this stage in its life cycle is 6 cm long with an intense instinct to swim upstream. This instinct allows them to scale any scenario and attempt to make it to their permanent habitat. During this migration, the eels are not presented with many predators as they are not commonly preyed on during the eel's life cycle stage. This low number of predators could also affect the nocturnal nature of the eels during this time. They chose to swim upstream during the night hours and hide under banks and rockets of the river during the day. Two weeks into this migration, the eels develop a black coloring and metamorphosis from elvers to brown-stage eels to continue their journey.

The brown-stage, also known as the yellow stage, stage of the eel's life lasts for 5–10 years, and during this time, the eel feeds on worms and insects. The characteristics of this stage include a dull pigment with a grey, brown, and greenish top and white underbelly. This pigment is related to the environment as it relies significantly on the color of the water. The eels grow to around their adult size in this stage as well during this time, which is up to 57 – 60 cm for females and 35 cm for males. At 30 cm, the eels grow sexual organs for the first time and prepare to make their great migration.

Once these eels reach adulthood, they develop a silvery color under their skin. This change in appearance signaling that they are entering their last stage of life, the silver stage. During this time, the eels prepare to migrate to the spawning area by naturally producing more oil in their body. This oil is stored in the muscles of the eels and is approximately 20% of their body mass. Once the appropriate content of the oil is reached, the eels stop feeding. During the autumn and generally on the last quarter of the moon, the eels migrate downstream to the center of the pacific.[4]

Life history and habitat

The Japanese eel and other anguillid eels live in freshwater and estuaries, an area where a freshwater river meets the ocean.

Since then, more pre-leptocephali were collected at sea, and even Japanese eel eggs have been collected and genetically identified on the research vessel. The collections of eggs and recently hatched larvae have been made along the western side of the seamount chain of the West Mariana Ridge. Mature adults of the Japanese eel and giant mottled eel were captured using large midwater trawls in 2008 by Japanese scientists at the Fisheries Research Agency.[8] The adults of the Japanese eel appear to spawn in the upper few hundred meters of the ocean, based on the recent catches of their spawning adults, eggs, and newly hatched larvae. The timing of catches of eggs and larvae and the ages of larger larvae have shown that Japanese eels only spawn during the few days just before the new moon period of each month during their spawning season.

After hatching in the ocean, the leptocephali are carried westward by the North Equatorial Current and then northward by the Kuroshio Current to East Asia. before they metamorphose into the glass eel stage. The glass eels then enter the estuaries and headwaters of rivers and many travel upstream. In fresh water and estuaries, the diet of yellow eels consists mainly of shrimp, other crustaceans, aquatic insects, and small fishes.[9]

Conservation

Threats

In the case of the Japanese eel's spawning is likely affected by the north–south shifts of a salinity front created by an area of low-salinity waters resulting from tropical rainfall. The front is thought to be detected by the adult spawning eels and to affect the latitudes at which they spawn. A northward shift in the front that occurred over the past 30 years appears to have occurred, which could cause more larvae to be retained in eddies offshore in the region east of Taiwan, and southward shifts in the salinity front have been observed in recent years that could increase southward transport into the Mindanao Current that flows into the Celebes Sea. These types of unfavorable larval transport are thought to reduce the recruitment success of the Japanese eels that reach river mouths as glass eels.[10]

The decline of the population of the Japanese eel is also directly related to the strong connection that the eel's life cycle has with the temperature of the water. This species relies on this environmental signal to know when to migrate in and out of their fresh water habitat; thus, the change in water temperature is directly proportional to the decline in population size. These rising water temperatures to ocean acidification and the thinning of the ozone layer. These eels are having a more challenging time knowing when to migrate. When migrating into their freshwater habitats, they prefer 8 to 10 degrees Celsius, a temperature usually reached in the autumn months but is getting later and later.[4]

Another factor that is effecting the Japanese eels is habitats loss. The coast is becoming a more preferred location for humans to live as the climate and pollution continues to worsen taking away from the habitat of these eels. On average from 1970s–2010s, 76.8% of the Japanese eels habitat is lost to human development.[11]

Status

The Japanese Eel is considered an endangered species by IUCN. The last time that this species was assessed in November 2018 and according to that assessment the population size is still decreasing.[12]

Efforts

There are multiple preservation effectors that the Japanese government is undertaking to slow or stop the extinction of this highly important species for their consumption. In 2015 the Inland Water Fishery Promotion Act was put in place preventing the fishing and culturing of eels without the proper permit. The goal of this act was to slow down the over fishing of the Japanese eel and control the number of eels being taken into captivity. In the future there is a law being placed that in December 2023 that makes fishing glass eels without a permit punishable with up to 3 years in prison or a 30 million Japanese yen fine. There have also been efforts made to stop the habitat loss of this species through the Nature-oriented river works. The high price and demand of this species means that there is also need for the Act on "Ensuring the Proper Domestic Distribution and Importation of Specified Aquatic Animals and Plants" that prohibits harvesting and culturing these eels without a permit that was put in place in 2020.[13]

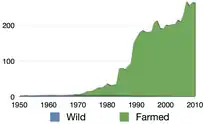

Aquaculture

The culturing of eels was started in Japan in 1894 and has become the most significant eel culture industry in the world since. Japan is the biggest consumer and producer of eels generating approximately 70 - 90% of the eel population as of 1991. The farming of the Japanese eel is challenging due to the breeding habits. Scientists and farmers have never been able to breed an eel, so this species' agriculture relies heavily on their catch in their elver stage.[15] A net is strewn across the rivers that these eels migrate up in the early autumn, and then they are transported to cultured ponds to grow to commercial size. The female eel grows to a much bigger size and has a longer life span than the male eel therefor; the cultured population is made up of 90% female eel. The heavy farming of this species has negatively impacted the conservation of the species; however, the production and consumption have not slowed.[4]

Scientific and medical use

| Bilirubin-inducible green fluorescent protein UnaG | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||

| Organism | |||||||

| Symbol | UnaG | ||||||

| UniProt | P0DM59 | ||||||

| |||||||

The Japanese eel has the ability to produce the protein UnaG which makes it unique among vertebrates. This protein is only found in the muscles of this species of eels making it a rare commodity. UnaG has demonstrated utility in life sciences and can be used to fluorescently label cells and tag proteins when exogenously expressed.[16] This protein has been used in an experimental diagnostic test to assess liver function.[17]

Consumption

As a food product, the Japanese eel is commonly referred to as unagi or kabayaki, with the latter being the method which the eels are often prepared. Kabayaki eels are prepared by being cut into fillets, deboned, skewered, marinated in sweet soy sauce (usually tare sauce) and then grilled. Japanese eels that have been grilled without tare sauce and seasoned only with salt are referred as Shirayaki.[18] Eels are eaten all year round in Japan.

Dishes made with Japanese eel include unajū, a dish consisting of the better cuts of eel served in a lacquered box over steamed rice, and unadon, a donburi type dish where fillets of eels are served over rice in a large bowl.[19] Japanese eel is also served as sushi, commonly called unagi sushi. Some notable types include unakyu, a type of sushi containing eel and cucumber, and rock and roll, a western-style sushi made with eel and avocado.

The Japanese eel contains a protein toxin in its blood that can cause harm to any mammals that ingest it, including humans.[20] However, there is no need for any special procedures as temperatures of 58-70 °C (136-158 °F) destroy the toxin.[21] Thus, Japanese eels are always cooked before consuption, even unagi sushi. Eels intended to be used in sushi are usually sold in pre-cooked fillets by many sushi suppliers.[22]

Due to the decline of the population of the Japanese eels, they are often being substituted with European or American eels, even within Japan, where Japanese eels were commonly used.[22]

Japanese eels are a good source of a wide range of vitamins and minerals. A serving of 100 grams contains roughly 120% of vitamin B12, 53% of vitamin D and 126% of the recommended daily value of vitamin A.[23][24] They are also a source of vitamins such as B1, B2, E, D and niacin.[23] Minerals such as phosphorus, selenium, zinc and potassium are also present, along with traces of magnesium, copper, and iron.[23] Additionally, they are rich in dietary protein and contain a good amount of omega-3 fatty acids,[23] albeit not as much as other seafood, like sardines.[25] They contain relatively low quantities of mercury.[26][27]

References

- ↑ Pike, C.; Kaifu, K.; Crook, V.; Jacoby, D.; Gollock, M. (2020). "Anguilla japonica". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T166184A176493270. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T166184A176493270.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ "日本鰻". Local Sensei. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ↑ Vietnam Faunas, in creatures.net

- 1 2 3 4 Atsushi, Usui (1991). Eel culture. Fishing News Books. ISBN 0-85238-182-4. OCLC 1221090595.

- ↑ Chow, S.; Kurogi, H; Katayama, S; Ambe, D; Okazaki, M; Watanabe, T; Ichikawa, T; Kodama, M; Aoyama, J; Shinoda, A; Watanabe, S; Tsukamoto, K; Miyazaki, S; Kimiura, S; Yamada, Y; Nomura, K; Tanaka, H; Kazeto, Y; Hata, K; Handa, T; Tawa, A; Mochioka, N (2010). "Japanese eel Anguilla japonica do not assimilate nutrition during the oceanic spawning migration: Evidence from stable isotope analysis". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 402: 233–238. Bibcode:2010MEPS..402..233C. doi:10.3354/meps08448.

- ↑ Tsukamoto, Katsumi (23 February 2006). "Spawning of eels near a seamount". Nature. 439 (7079): 929. doi:10.1038/439929a. PMID 16495988. S2CID 4346565.

- ↑ Tsukamoto, Katsumi (April 1992). "Discovery of the spawning area for Japanese eel". Nature. 356 (6372): 789–791. Bibcode:1992Natur.356..789T. doi:10.1038/356789a0. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 4345902.

- ↑ Chow, S.; Kurogi, Hiroaki; Mochioka, Noritaka; Kaji, Shunji; Okazaki, Makoto; Tsukamoto, Katsumi (2009). "Discovery of mature freshwater eels in the open ocean". Fisheries Science. 75 (1): 257–259. Bibcode:2009FisSc..75..257C. doi:10.1007/s12562-008-0017-5. S2CID 39090269.

- ↑ Man, S.H.; Hodgkiss, I.J. (1981). Hong Kong freshwater fishes. Hong Kong: Wishing Printing Company. Urban Council. p. 75.

- ↑ Kimura, S.; Inoue, Takashi; Sugimoto, Takashige (2001). "Fluctuation in the distribution of low-salinity water in the North Equatorial Current and its effect on the larval transport of the Japanese eel". Fisheries Oceanography. 10 (1): 51–60. Bibcode:2001FisOc..10...51K. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2419.2001.00159.x.

- ↑ Chen, Jian-Ze; Huang, Shiang-Lin; Han, Yu-San (2014-12-05). "Impact of long-term habitat loss on the Japanese eel Anguilla japonica". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 151: 361–369. Bibcode:2014ECSS..151..361C. doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2014.06.004. ISSN 0272-7714.

- ↑ IUCN (2018-11-06). "Anguilla japonica: Pike, C., Kaifu, K., Crook, V., Jacoby, D. & Gollock, M.: The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T166184A176493270". doi:10.2305/iucn.uk.2020-3.rlts.t166184a176493270.en. S2CID 239784647.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Joint Press Release" (PDF). mofa. July 14, 2022. pp. 1–5.

- ↑ Based on data sourced from the FishStat database, FAO.

- ↑ Heinsbroek, L. T. N. (1991). "A review of eel culture in Japan and Europe". Aquaculture Research. 22 (1): 57–72. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2109.1991.tb00495.x. ISSN 1355-557X.

- ↑ Kumagai, Akiko; Ando, Ryoko; Miyatake, Hideyuki; Greimel, Peter; Kobayashi, Toshihide; Hirabayashi, Yoshio; Shimogori, Tomomi; Miyawaki, Atsushi (June 2013). "A Bilirubin-Inducible Fluorescent Protein from Eel Muscle". Cell. 153 (7): 1602–1611. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.038. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 23768684.

- ↑ Baker, Monya (2013). "First Fluorescent Protein Identified in a Vertebrate Animal". Scientific American. Archived from the original on November 20, 2019. Retrieved 2020-05-23.

- ↑ Media, USEN. "Unagi and Anago: 8 Wonderful Ways to Eat Japanese Eel". SAVOR JAPAN. Retrieved 2022-12-11.

- ↑ Richie, Donald (1985). A taste of Japan : food fact and fable : what the people eat : customs and etiquette. Kodansha International. pp. 62–69. ISBN 978-4770017079.

- ↑ Yoshida, Mireiyu; Sone, Seiji; Shiomi, Kazuo (December 2008). "Purification and characterization of a proteinaceous toxin from the Serum of Japanese eel Anguilla japonica". The Protein Journal. 27 (7–8): 450–454. doi:10.1007/s10930-008-9155-y. ISSN 1572-3887. PMID 19015964. S2CID 207199774.

- ↑ Tesch, Friedrich-Wilhelm (2003). The eel. J. E. Thorpe (3rd ed.). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4051-7343-8. OCLC 184983522.

- 1 2 (PDF). 2010-07-06 https://web.archive.org/web/20100706014923/http://www.montereybayaquarium.org/cr/cr_seafoodwatch/content/media/MBA_SeafoodWatch_UnagiReport.pdf. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-06. Retrieved 2022-11-30.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - 1 2 3 4 "FoodData Central". fdc.nal.usda.gov. Retrieved 2022-12-11.

- ↑ Nutrition, Center for Food Safety and Applied (2022-02-25). "Daily Value on the New Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA.

- ↑ "FoodData Central". fdc.nal.usda.gov. Retrieved 2022-12-11.

- ↑ Sato, Naoyuki; Ishii, Keiko; Satoh, Akio; Tanaka, Yasuo; Hidaka, Toshio; Nagaoka, Noboru (December 2005). "[Residues of total mercury and methyl mercury in eel products]". Shokuhin Eiseigaku Zasshi. Journal of the Food Hygienic Society of Japan. 46 (6): 298–304. doi:10.3358/shokueishi.46.298. ISSN 0015-6426. PMID 16440794.

- ↑ Nutrition, Center for Food Safety and Applied (2022-02-25). "Mercury Levels in Commercial Fish and Shellfish (1990-2012)". FDA.