| National Pacification Army | |

|---|---|

| Anguojun / Ankuochun | |

.svg.png.webp) Flag of the Beiyang government and the National Pacification Army until December 1928 (Five Races Under One Union)  Emblem of the National Pacification Army (Beiyang star) | |

| Active | 1926–1928 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | Beiyang government Fengtian clique |

| Type | Army |

| Nickname(s) | "NPA" |

| Equipment | 7.92mm Year-13 Rifle (Shisannian-shi buqiang)[1]: 65 8cm Mortars (1100 produced 1924-1928), 150mm Heavy Mortars, 37mm Infantry Guns, 75mm Field Guns, 77mm Cannons, 105mm Cannons, 150mm Howitzers, various German (Mauser) and Japanese (Arisaka) rifles[1]: 72–3 |

| Engagements | Northern Expedition |

| Commanders | |

| Commander-in-Chief (Generalissimo after June 1927) | Zhang Zuolin |

| Chief of Staff | Yang Yuting |

| National Pacification Army | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 安國軍 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 安国军 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | National Pacification Army | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The National Pacification Army (NPA), also known as the Anguojun or Ankuochun (Chinese: 安國軍), was a warlord coalition led by Fengtian clique General Zhang Zuolin, and was the military arm of the Beiyang government of the Republic of China during its existence.

The army was formed in November 1926 after the Fengtian victory in the Anti-Fengtian War, the NPA was tasked with countering the advance of the Kuomintang (KMT)-aligned National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of Chiang Kai-shek, who had launched the Northern Expedition in June 1926.[1]: 3 In addition to its Fengtian Army core, the NPA also included Zhili clique generals, such as Sun Chuanfang.[1]: 18 The NPA suffered a series of serious military defeats inflicted by Chiang and his warlord allies, including Feng Yuxiang, Li Zongren and Yan Xishan. On the southern front, the NPA was pushed back from Jiangsu and Henan after fierce fighting against the Guominjun and the NRA. On the western front, they fought Shanxi forces under Yan Xishan. Following these setbacks, a conference of NPA leaders in June 1927 established a military government and proclaimed Zhang Zuolin as Generalissimo, whereupon all military and civilian power was placed in his hands.

Despite having achieved a few victories in mid-1927 in Jiangsu and extensive victories in Shanxi, the NPA could not defeat the Kuomintang forces and soon retreated north and east of Tianjin. Following Zhang Zuolin's assassination by the Japanese Kwantung Army in the Huanggutun Incident on 4 June 1928, he was succeeded by his son, Zhang Xueliang, who disbanded the National Pacification Army and swore allegiance to the Kuomintang government in Nanjing.

Background

China fragmented into various warlord factions as part of the tumultuous Warlord Era during the 1910s which started from the Xinhai Revolution. Many provinces became autonomous under their ruling generals. Following the National Protection War against Beiyang Army general-turned-emperor Yuan Shikai, China became balkanized into a collection of regional power networks, the feud between different factions intensified, and warlordism was born.[2]

The Fengtian clique had been formed under Zhang Zuolin, who was the local hegemon in Manchuria. Zhang's Fengtian Army was the backbone of his influence and allowed him to make mutually-beneficial alliances with local elites.[3]: 66 In response to the growing dominance of China by the Anhui clique, an opposing warlord group consisting of the Fengtian and Wu Peifu-led Zhili cliques banded together. This coalition expelled the Anhui clique from Beijing in the Zhili–Anhui War, pushing them southwards and allowing the Fengtian and Zhili cliques to jointly control the capital.[3]: 63–65 However, this order fell, with the Zhili and Fengtian cliques going to war in the First Zhili–Fengtian War.[4] Zhili won, pushing Fengtian back to Manchuria.[5]

In 1924, Zhili-aligned Jiangsu governor Qi Xieyuan declared war on Fengtian-allied Zhejiang governor Lu Yongxiang, sparking a new conflict between the Fengtian and Zhili cliques, called the Second Zhili–Fengtian War. The decisive moment of the conflict came on 30 October 1924, when warlord Feng Yuxiang broke from the Zhili clique, declared the establishment of the independent Guominjun, and aligned with the Fengtian in his Beijing Coup.[6]: 164–165 This led to an overwhelming Fengtian victory, the removal of the Zhili clique from the capital and Cao Kun from the presidency of the Republic of China, and placed Zhang Zuolin in control of the Beiyang government.[6]: 165

Fengtian thus took control of Zhili and Shandong provinces, with the Zhili clique routed southwards, where warlord Sun Chuanfang established control of the provinces of Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Anhui, Fujian, and Jiangxi.[7] The army he created he named the Allied Army of the Five Provinces (Chinese: 五省聯軍).[1]: 106 The fragile peace following the Second Zhili–Fengtian War did not last long, as Feng Yuxiang and Zhang Zuolin quickly turned against each other. Both had been seeking an alliance with the Zhili clique, but Wu Peifu, in an attempt at revenge, sided with Zhang in the Anti-Fengtian War.[3]: 66 In October 1925, Sun Chuanfang began the invasion of Jiangsu, and Feng began his invasion of Shandong, which was now under the control of Fengtian general Zhang Zongchang. In November 1925, general Guo Songling turned against Zhang Zuolin, siding with Feng. In January 1926, Zhang launched an offensive, ordering his troops in Fengtian and Shandong provinces to invade Beijing and Tianjin.[1]: 103–7

By mid-1926, Zhang and his Fengtian clique held the dominant stake in the Beiyang government.[1]: 106 At around the same time, in June 1926, the rival Kuomintang government, based in the southern city of Guangzhou, launched the Northern Expedition. This posed a serious threat to the northern cliques, and countering the Kuomintang advance would be the raison d'être of the National Pacification Army.[1]: 3 Zhang was also pressured by a destabilization of the government in Beijing as well as Japanese and Soviet influence. With Zhang having pushed Feng away from Beijing, beyond the Nankou Pass, and with the collapse of Wu Peifu's army in the wake of the NRA advance in Hunan and Hubei provinces in late 1926, the Fengtian clique cemented its position both as leader of the Beiyang government and as the main military clique in northern China.[1]: 112–13

History

Establishment (1926)

Following the period of chaos in the aftermath of the Anti-Fengtian War, and the disintegration of Guominjun and Zhili power in Beijing, Zhang Zuolin brought together his Fengtian Army commanders and other, non-affiliated warlords such as Sun Chuanfang and Yan Xishan in November 1926 to discuss the situation. Zhang declared the establishment of the National Pacification Army, a unified military of which he was to be the commander-in-chief. He was officially elected to that post at a conference in December 1926.[1]: 86 [8] Sun and Zhang Zhongchang were appointed deputy commanders of the new force, and its headquarters was established in the Pukou–Nanjing area.[9]: 96–97 According to historian Donald Jordan, the name "National Pacification Army" is rooted in "engaging in war to achieve peace", a traditional idea in China's long history of dynastic leaders fighting to reunite the country. At the time of the NPA's establishment, Zhang Zuolin vowed to save China from the "red menace", an attack on the Kuomintang's United Front with the Chinese communists, and their Soviet and Comintern backers. The NPA at this time consisted of 500,000 men.[9]: 96–97

At the establishment of the NPA in November 1926, Zhang Zuolin had two main allies. The first was Zhang Zongchang, a Fengtian commander and Governor of Shandong province, who commanded the de facto independent Zhili–Shandong Army. This force was a merger of Zhang's "Shandong Army" and the Zhili Army of his lieutenant, Chu Yupu.[10] Although Zhang Zongchang's army was powerful and separate from the Fengtian army itself, Zhang Zongchang still saw himself as subordinate to Zhang Zuolin. His second ally was Sun Chuanfang, a Zhili warlord active in central China. After joining the NPA, Sun's army coordinated its movements with Zhang, and after Sun was driven out of Jiangsu and Zhejiang in early 1927, he was supplied by the Fengtian clique. Even though Sun was totally financially dependent on the Fengtian clique, he was still able to make his own decisions when they would benefit him.[1]: 67 Zhili clique general Wu Peifu was considered a part of the NPA, but his power-base was destroyed when the KMT conquered Hubei province in late 1926.[8]

The NPA was essentially a new version of Zhang Zuolin's Eastern Three Provinces Defense Headquarters, with its main difference being that it was located in Beijing, rather than Mukden (now known as Shenyang, formerly known as Fengtian). Furthermore, the NPA made attempts to gain the allegiance of non-Fengtian-affiliated warlord armies in northern China. Decisions were made by the NPA leaders in conferences at the NPA headquarters in Beijing, with Zhang Zuolin, Zhang Xueliang, Yang Yuting, Yu Guohan, Zhang Zuoxiang, Wu Junsheng, Wang Yongjiang, Sun Chuanfang, and Zhang Zongchang frequently attending. The leadership of the NPA was, in essence, a military council under the leadership of Zhang Zuolin, who had to plan his military activities based on those of his allies and the opinions of subordinates such as Yang Yuting. Even so, when Zhang was strongly convinced about some matter, he had ability to ignore the opinions of his generals.[1]: 68–70

Setbacks in Henan and Jiangsu (1927)

In early 1927, the forces of the NPA and the National Revolutionary Army were facing off in Henan and Jiangsu. In May 1927, the Japanese, represented by Colonel Doihara Kenji, sent a message to Shanxi warlord Yan Xishan, asking him to establish peace between the NRA and the NPA and "take over northern China". With Japanese support guaranteed, Yan moved to join the KMT.[1]: 120 [11] Zhang Zuolin declared himself Generalissimo on the 18th as Fengtian–KMT negotiations deteriorated,[1]: 134 [12] forming a new military government. The Guominjun were also involved in the battle in Henan. Its leader, Feng Yuxiang, had joined the Kuomintang in November 1926, and was contesting NPA forces in Henan by December as the commander of the Central Route Army of the Northern Expedition, with 100,000 men fighting in western Henan.[13]: 317–8 The Fengtian clique declared that Zhang Zuolin would be elected president of the Beiyang government once the provinces north of the Yangtze River were secured. This brought Zhang to launch a new offensive in Henan in spring 1927, mirroring a new offensive by the anti-Chiang Kai-shek Wuhan KMT government led by Tang Shengzhi. During May, 100,000 of the Wuhan government's troops were wounded, while Feng's casualties numbered 400.[12] As Yan and Feng swore allegiance to Chiang's newly formed alternative to the Wuhan government, the Nanjing KMT government, the NPA was forced to abandon the two provinces of Henan and Jiangsu, and the broader NPA strategy was abandoned too.[1]: 121–2 Feng continued the drive northwards, pushing against NPA forces in July 1927.[13]: 319

Two other major Chinese battlegrounds in this period were Jiangsu, (specifically the city of Xuzhou) and Shanxi. With NPA forces expelling the NRA from Xuzhou in August 1927,[1]: 120 the NRA and the Guominjun cooperated to defend against NPA offensives led by Sun Chuanfang in a last-ditch attempt to retake his original territories. By August, the front line had moved to southern Jiangsu, with the NRA being pushed to Nanjing, leading Yan Xishan to revert to neutrality. However, in late August, Sun Chuanfang was being pushed back, and he lost 50,000 men throughout September.[12] Jiangsu was where Feng Yuxiang's force was mainly concentrated. Towards the north, Zhang Zuolin was fighting Yan Xishan on a different front. Previously, Yan had been straddling the fence, taking a neutral stance militarily, although favoring the KMT (Shanxi formally joined the KMT in April).[14] However, in late August 1927, Zhang attacked Yan's soldiers in Shijiazhuang, who were forced to retreat to Shanxi. This tipped the balance, and Yan began an offensive along the Beijing-Suiyuan Railroad in October, opening up a new front of fighting between the KMT and the Anguojun.[13]: 321

Decline (1927–1928)

Zhang Zuolin's military government had almost attained international recognition—British minister to China Sir Miles Lampson was sympathetic to the warlords as their military situation seemed to improve in mid-1927; the fighting on the Jiangsu front seemed to be favoring them. Gaining international recognition was crucial to the Beiyang government, as it would add another layer of legitimacy and help reverse the unequal treaties, which was one of the main goals of the Kuomintang movement against the warlords. When Yang Yuting asked for financial help from Lampson, Lampson was "friendly and sympathetic", and suggested that "many things might be possible" if the NPA managed to win the war. However, this was short-lived, as the NPA could not hold out for long enough to gain foreign recognition. Sun Chuanfang's defeat in Jiangsu and the subsequent defeat of Zhang Zongchang on the Shandong front in November turned the tides of the war, although the NPA had secured some victories in Shanxi in September.[1]: 133–4

In November 1927, the NRA launched an offensive, taking Mingguang, Fengyang, and then Bengbu, the capital of Anhui. Sun Chuanfang tried to retake Pengpu by cutting the NRA forces in the city off from its connection with the other KMT forces, but he was forced to retreat to the Huai River valley. The NRA advanced even further, taking Guzhen and pushing Sun to northern Jiangsu. Ignoring his differences and disagreements with Zhang Zongchang and his 150,000 men in Shandong, Sun joined him in attempting to push the NRA back. Xuzhou came under siege, but Zhang and Sun responded by sending 60,000 and 10,000 soldiers (respectively) onto the railroad from Xuzhou and launching an offensive on the rail line on 12 December. Although the NPA had air support from White Russian, Japanese, and European pilots, they could not succeed, and were pushed back within two days.[15]: 167 On 16 December 1927, the NPA were pushed out of Xuzhou.[13]: 319 Sun's Long-Hai railroad front subsequently disintegrated and the NPA were forced to retreat to Shandong and dig in.[15]: 168

At the beginning of 1928, the now severely weakened National Pacification Army was being pushed back. The coalition between Chiang, Feng, Yan, and Li Zongren surrounded it to the south, with troops in Shanxi, Henan, and southern Shandong. Yan's forces had flanked the west of the Beijing–Tianjin railway in early 1928.[13]: 319 The NPA still planned to retake Henan, but they were in no position to do so. In mid-April, Yan was able to expel the NPA and launch his own counteroffensive, pushing them out of Shuochou. Nearly one million soldiers participated in the battle along the railway connecting Shanxi with Beijing. In order to immobilize the railways and artillery on trains, Yan and Feng launched a joint siege of Shijiazhuang, a major railway hub, which fell on 9 May. Yan took Zhangjiakou on 25 May. Feng's forces were moving up the Beijing–Hankou railway, forcing the NPA to split their defense.[16] In April, the Shandong front collapsed as Zhang Zongchang was fully defeated. As NRA forces reached Beijing, Zhang directed 200,000 men to hold the southern front. Feng was pushed back from Baoding to Dingzhou, where Feng was unable to advance from. However, Feng defeated the NPA on the eastern front and immediately attempted to sever NPA communications through cutting them off from rail lines. Finally, on 3 June, Zhang decided to move his headquarters back to Manchuria. Having observed the dire state of affairs of the NPA in Beijing, feeling alarmed at the potential fate of Japanese interests in Manchuria should the Kuomintang be victorious, and believing that Zhang was too uncooperative, officers of the Japanese Kwantung Army threatened that they would block Zhang Zuolin from returning to Mukden if he made an agreement with the KMT.[17] As he was returning to Manchuria following the abandonment of Beijing, his train was blown up by officers of the Kwantung Army on 4 June 1928 in what was called the Huanggutun incident.[1]: 135

Dissolution under Zhang Xueliang (1928)

Following the death of Zhang Zuolin, his son, Zhang Xueliang, took power. Yang Yuting became fully responsible for the military strategy of the NPA, which had now been severely reduced, assuming the role of Commander-in-Chief of the Eastern Three Provinces Defense Headquarters in July 1928.[18] Although he seemed to support siding with Nanjing, he believed that Fengtian–KMT unity would not last. He advised Zhang Xueliang to hold the line east of Shanhaiguan and Rehe Province, as well as asking for him to take control of the remnants of Sun Chuanfang's and Zhang Zongchang's armies, each consisting of over 50,000 men, who were now situated between Tangshan and Shanhaiguan. Yang wanted to capitalize on KMT disagreements and infighting in order to prepare for a comeback of the NPA.[1]: 136

As Yang grew more and more powerful, Zhang Xueliang became more suspicious of him. He was paranoid that Yang would use Japanese support to replace his position. Additionally, Yang often did not listen to orders or recommendations from Zhang, even though he was officially his subordinate.[18] Zhang therefore ordered the executions of Yang and his associate, Heilongjiang governor Chang Yinhuai,[19] thereby ending the leadership of the internal clique of Fengtian officers that had attended the Imperial Japanese Army Academy and allowing Zhang to take full control over the affairs of the Fengtian clique and the NPA.[1]: 136–7 Zhang sent a telegram to Nanjing, justifying his execution of Yang and Chang.[20]

Zhang Xueliang decided to cut down the Fengtian Army and funding to the Mukden Arsenal to fix the financial situation of Manchuria. It was here that he completely disbanded the National Pacification Army, with only Yu Xuezhong's army turning to Fengtian, while the rest of the former NPA armies were absorbed by NRA or Shanxi forces.[1]: 137 Many of the former NPA forces east of Tianjin were cleared up in September 1928.[21]

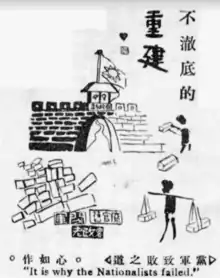

Towards the end of the Northern Expedition, the KMT government in Nanjing began to be recognized by foreign powers as the legitimate government of China. However, this led to a weakening of the Chinese military presence and position in Manchuria. Zhang Xueliang, succeeding his father, Zhang Zuolin, made a decision to negotiate with KMT leaders in Nanjing for recognition. Nanjing decided, however, that the NPA would be fully disbanded, leading to the Northeast Flag Replacement. In its place, local warlords began to dominate Manchuria; the people of the northeastern provinces suffered from increasing societal disorder, and Chinese authority collapsed in the region, paving the way for the 1931 Japanese invasion following the Mukden Incident.[1]: 93

Structure

Command

The Military Academy of the Eastern Three Provinces trained 7,971 officers from 1919 to 1930. These new officers formed the backbone of the lower levels of the NPA military command structure. At the top were graduates of Baoding Military Academy, who also served as instructors at the Military Academy of the Eastern Three Provinces.[1]: 73

The command of the Fengtian clique was dominated by people such as Yang Yuting, who held the positions of Chief of Staff and head of the Mukden Arsenal, known as the Shikan clique as they had all studied at the Imperial Japanese Army Academy. This faction had the upper hand over the Staff College Clique, who studied at the Staff College of Beijing.[1]: 66 This faction was led by Guo Songling. Guo had rebelled in 1925, severely decreasing the influence of the Staff College Clique.[22] With Guo dead, Zhang Zuolin headed the Staff College Clique.[18]

Composition

By 1927, the Fengtian Army was estimated to have 8 gun regiments. US intelligence reported that they also had seven 77mm field gun regiments with 420 guns (36 per regiment, 12 per battalion) as well as a regiment of twenty-four 150mm guns.[23] The Fengtian Army consisted of 220,000 men in 1928. Sun Chuanfang's army consisted of 200,000 men by 1927, despite two of his divisions defecting to the NRA. During his defense at the Yangtze, Sun had 70,000 troops, split up into 11 divisions and 6 mixed brigades. Access to equipment was so limited that some soldiers were armed with spears instead of guns. The battle at Longtan, near Nanjing, caused 30,000 casualties for Sun, with 35,000 rifles and 30 field guns taken by the NRA. By the end of the battle, Sun was left with only 10,000 men.[24]

The Zhili–Shandong Army (consisting of men from the provinces of Zhili and Shandong) consisted of 150,000 men and 165 pieces of artillery by 1927. There were also 4,000 White Russian mercenaries serving in the army, and 2,000 boys (ages averaging around 10) led by one of Zhang Zongchang's sons. These boys were given special short rifles.[24] The Zhili–Shandong Army was reported to have 160 pieces of field artillery, of which 40 were in disrepair.[23]

Propaganda

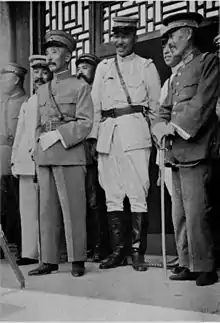

Zhang Zuolin, as he saw himself as lacking the political power, styled himself as Generalissimo, rather than President as Sun Yat-Sen had done, from the start of the military government in 1927. He thus appeared in military uniform rather than in civilian clothes. Popular pro-Ankuochun slogans included: "May the Chinese Republic live thousands of years", "Eliminate violence at home", and "Counter foreign aggression". The Ankuochun made themselves look like the bringers of peace and order to China, against the forces of the Kuomintang, and their Soviet and communist backers.[1]: 85–6

Additionally, Ankuochun propaganda portrayed Zhang Zuolin's son, Zhang Xueliang, the "Light in the North", as a young and patriotic "son of China". They tried to reconcile the ideals of Zhang Zuolin and Zhang Xueliang with those of Sun Yat-sen by saying that the Zhangs endorsed the Three Principles of the People.[1]: 86 Zhang Xueliang was often portrayed in a western-style suit to show his sophistication. He was also portrayed as the successor to Sun Yat-sen.[1]: 87

As for the Ankuochun generals, propaganda portrayed them as honorable and legitimate men; their honor and legitimacy stemming from their association with important figures, their diverse backgrounds, their skills, and their willingness to expel foreign influence.[1]: 87–88

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Chi Man Kwong (28 February 2017). War and Geopolitics in Interwar Manchuria: Zhang Zuolin and the Fengtian Clique during the Northern Expedition. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-34084-8.

- ↑ Edward Allen McCord (1993). The Power of the Gun: The Emergence of Modern Chinese Warlordism. University of California Press. pp. 205–9. ISBN 978-0-520-08128-4.

- 1 2 3 Christopher R. Lew; Edwin Pak-wah Leung (29 July 2013). Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Civil War. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7874-7.

- ↑ Tjio Kayloe (15 September 2017). The Unfinished Revolution: Sun Yat-Sen and the Struggle for Modern China. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. p. 341. ISBN 978-981-4779-67-8.

- ↑ Anthony B. Chan (1 January 2011). Arming the Chinese: The Western Armaments Trade in Warlord China, 1920-28, Second Edition. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-1992-3.

- 1 2 Bruce A. Elleman (2005). Modern Chinese Warfare, 1795-1989. Routledge. ISBN 1134610092.

- ↑ Arthur Waldron (16 October 2003). From War to Nationalism: China's Turning Point, 1924-1925. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52332-5.

- 1 2 United States. Department of State (1926). Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 659.

- 1 2 Jordan, Donald (1976). The northern expedition : China's national revolution of 1926-1928. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii. ISBN 978-0-8248-8087-3. OCLC 657972971.

- ↑ Zhanchen Mi (1981). The life of General Yang Hucheng. Joint Pub. Co. p. 39. ISBN 978-962-04-0099-5.

- ↑ Andrew P. Dunne (1996). International Theory: To the Brink and Beyond. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-313-30078-3.

- 1 2 3 Jeffrey S. Dixon; Meredith Reid Sarkees (18 September 2015). A Guide to Intra-state Wars: An Examination of Civil, Regional, and Intercommunal Wars, 1816-2014. SAGE Publications. p. 482. ISBN 978-1-5063-0081-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The Winning Over of the Big Warlords: Feng and Yen.” The Northern Expedition: China's National Revolution of 1926–1928, by DONALD A. JORDAN, University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu, 1976, pp. 316–322. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv9zck3k.36. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ↑ Hsi-sheng Chi (1969). The Chinese Warlord System: 1916 to 1928. American University, Center for Research in Social Systems. p. 48.

- 1 2 The September Government and the Northern Expedition. The Northern Expedition: China's National Revolution of 1926–1928, by DONALD A. JORDAN, University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu, 1976, pp. 164–172. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv9zck3k.21. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ↑ The Peking Campaign: Completion of the Military Unification. The Northern Expedition: China's National Revolution of 1926–1928, by DONALD A. JORDAN, University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu, 1976, pp. 186–194. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv9zck3k.23. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ↑ Wang, Ke-wen (1998). Modern China: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Nationalism. Taylor & Francis. p. 454. ISBN 978-0-419-22160-9.

- 1 2 3 Mayumi Itoh (3 October 2016). The Making of China's War with Japan: Zhou Enlai and Zhang Xueliang. Springer. p. 74. ISBN 978-981-10-0494-0.

- ↑ The Chinese Students' Monthly. Chinese Students' Alliance. 1928. p. 241.

- ↑ Rana Mitter; University Lecturer in History and Politics of Modern China Rana Mitter (2 December 2000). The Manchurian Myth: Nationalism, Resistance, and Collaboration in Modern China. University of California Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-520-22111-6.

- ↑ Robert L. Jarman (2001). China Political Reports 1911-1960. Archive Editions. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-85207-930-7.

- ↑ Tony Jaques (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: P-Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 1016–. ISBN 978-0-313-33539-6.

- 1 2 United States. War Dept. General Staff (1978). United States military intelligence [1917-1927]. Garland Pub. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8240-3025-4.

- 1 2 Philip Jowett (20 November 2013). China's Wars: Rousing the Dragon 1894-1949. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 121–2. ISBN 978-1-4728-0673-4.