The Chronicle of Aniane (or Annals of Aniane) is an anonymous Latin history covering the rise of the Carolingian family from 670 to 840. It was composed by a monk of the Abbey of Aniane.

The Chronicle of Aniane is closely related to the Chronicle of Moissac and the two have not always been adequately distinguished. For the years 670–812, the two chronicles draw on the same sources, including a lost source from southern France. A gap in the Chronicle of Moissac for the years 716–770 makes the Chronicle of Aniane the only surviving text to preserve information from this lost source for those years.

The date of composition of the Chronicle of Aniane is unknown. It is found in a single manuscript copy from the early twelfth century, but may have been composed much earlier.

Date, place and author

The Chronicle was composed by a monk of the Abbey of Aniane.[2] The date of its composition is unknown. It has been dated as early as the ninth and as late as the twelfth century.[3] J. M. J. G. Kats and D. Claszen suggest an "Aniane prototype" was composed in the ninth century and given its final form only in the twelfth.[4] According to Walter Kettemann, the sole surviving copy of the Chronicle of Aniane was used as a source for some passages in On the Holiness, Merits and Glory of the Miracles of the Blessed Charlemagne, written between about 1165 and 1170. He dates the Chronicle to the early twelfth century, but argues that its prototype was composed at Aniane between the later ninth century and 1017.[3] It or a related chronicle was probably used as a source for the Chronicon Coxanense, completed before 985.[5]

Manuscripts

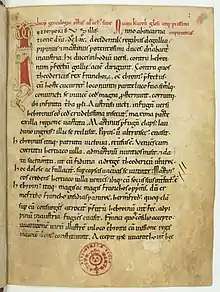

The Chronicle of Aniane is found today in a single manuscript codex now in the National Library of France, BN lat. 5941, where it is the first text at folios 2r–49v.[6] It was formerly in the possession of Étienne Baluze until his death in 1718, when it passed to the Bibliothèque nationale. It still bears his pressmark, Bal. 88.[7] It is sometimes called the Codex Rivipulliensis, because it once belonged to the monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll.[7]

The copy of the Chronicle in BN lat. 5941 is dated palaeographically to the late eleventh or early twelfth century. Most scholars believe it was copied at Aniane, but Jean Dufour argued that the script is similar to that of another manuscript produced in the Abbey of Arles-sur-Tech.[3][8] The contents of BN lat. 5941, however, were only bound together as a codex several centuries after the Chronicle itself was copied, probably in the fourteenth century.[3][9] The Chronicle is followed in the codex by the Deeds of the Counts of Barcelona; a short epicedion (funeral elegy) for Count Raymond Borrell of Barcelona; a letter purportedly from Prester John to Emperor Manuel Komnenos; a note on the marriages and offspring of Saint Anne; and a note based on the canons of the Council of Rome of 1082.[3]

In the seventeenth century, Pierre de Marca may have had access to a different copy of the Chronicle not otherwise known to scholarship. In his Marca Hispanica, published posthumously by Baluze in 1688, he cites the "Annals of Aniane" in ways that suggest he had a different copy of the chronicle than the one in BN lat. 5941.[10] He cites it for the date of the Battle of the River Berre in 737.[10]

Title

The Chronicle of Aniane is known by several titles. In the manuscript it is introduced with the rubric Genealogia, ortus, vel actus Caroli, atque piissimi Imperatoris ('Genealogy, origin, or deeds of Charles the most pious emperor').[6] The table of contents of the manuscript, a late addition, calls the first text Annalis monasterii Ananianensis, ab anno DCLXX usque ad an. DCCCXXI.[3] The library catalogue lists it under the rubric but adds, as an alternative short title, sive potius chronicum Anianense ('or rather the chronicle of Aniane').[6]

Today, the conventional Latin titles are Chronicon Anianense and Annales Anianenses, whence Aniane Chronicle and Aniane Annals (or Annals of Aniane).[2][11]

Content

The Chronicle of Aniane is essentially a history of the Carolingian family, charting its rise from 670 and the Battle of Lucofao through to the death of the Emperor Louis the Pious in 840.[6][9] Ideologically, the chronicle is a pro-Carolingian work.[9] It belongs to a class of works that are continuations of the Greater Chronicle of the English historian Bede, a universal history down to 725.[2]

The Chronicle contains no original material, but it is the only surviving source for some material and "is a unique source for the years during the transition from Merovingian to Carolingian rule for which otherwise little information is left".[12] For the years 670–812, it draws on the same sources as the Chronicle of Moissac.[2] These include the original continuation of Bede, called the Universal Chronicle to 741, and a further continuation down to 818, called the "compiler's text", a text which does not survive independently but was the basis for the Chronicle of Aniane, the Chronicle of Moissac and the Chronicle of Uzès.[4] Among the sources used by the compiler were the Book of the History of the Franks, the Annals of Lorsch and a lost source known only as the "southern source".[2] Since the text of the Chronicle of Moissac for the years 716–770 is missing, the Chronicle of Aniane is the only source for the "compiler's text", including the lost "southern source", for the years 741–770.[12]

For later years down to 818, the Chronicle of Aniane draws on Einhard's Life of Charlemagne.[2][13] Structurally, the Chronicle consists of annals proper, covering all its years, down to folio 37r. This is followed without any break by a series of narrative passages on Louis the Pious, Benedict of Aniane and William of Gellone.[3]

Compared to the Chronicle of Moissac, that of Aniane has a more southern focus. It frequently omits local information from Austrasia and Neustria and also contains less on foreign matters. It records the foundation of Aniane, the entry into the monastery of a certain Count William in 806 and the transfer of Benedict of Aniane from the monastery to a place closer to Aachen in 814. It is less accurate than the Chronicle of Moissac. The Saxon campaign of 779–780 is transformed into an ahistorical Spanish campaign by the changing of a few key words.[14] It mis-dates Louis the Pious's siege of Barcelona to 803, while it actually took place in 800–801.[15] It is an independent source for the unusual name of Pope Leo III's father (Atzuppius) and a unique source for the name of his mother (Elizabeth).[16]

Editing history

Edmond Martène and Ursin Durand were the first to publish the Chronicle of Aniane, under the title Annales veteres Francorum ('old annals of the Franks') in 1729. In 1730, for the Histoire générale de Languedoc , Claude de Vic and Joseph Vaissète published extracts related to Aquitanian and Septimanian affairs from what they called the Annales d'Aniane. In both these early editions, the editors considered the text essentially as it relates to the Chronicle of Moissac.[17]

In 1739, for the Recueil des historiens des Gaules et de la France , Martin Bouquet produced a composite text by editing the Chronicle of Moissac and the Chronicle Aniane together, using the latter primarily to fill in the large gap in the former. The composite edited text he called simply the Chronique de Moissac.[6] Heinrich Pertz followed a similar approach in his edition for the Monumenta Germaniae Historica. He, too, considered the composite text to be a critical edition of the Chronicle of Moissac. This view became the dominant one and Pertz's text the most cited one for the next century. In 1870, while editing of the Histoire générale de Languedoc, Émile Mabille rejected the hypothesis (and thus editions) of Bouquet and Pertz, arguing that the Chronicle of Moissac and the Chronicle Aniane had to be treated as separate texts.[18]

In 2000, Kettemann edited the Chronicle Aniane anew for his doctoral dissertation on Benedict of Aniane. [19][20] According to Kats and Claszen, "Kettemann's synoptic edition of [the Chronicle Aniane] and the corresponding part of [the Chronicle of Moissac] make the contents of the former completely and clearly accessible for the first time."[12]

Notes

- ↑ Kats & Claszen 2012, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bate 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kats & Claszen 2012, pp. 33–36.

- 1 2 Kats & Claszen 2012, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Bisson 1990, pp. 285, 288.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kats & Claszen 2012, pp. 13–14.

- 1 2 Kats & Claszen 2012, p. 75.

- ↑ Bisson 1990, pp. 283–284.

- 1 2 3 Kramer 2021, p. 232.

- 1 2 Kats & Claszen 2012, pp. 69–71.

- ↑ Kats & Claszen 2012, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Kats & Claszen 2012, p. 17.

- ↑ Kats & Claszen 2012, p. 39.

- ↑ Kats & Claszen 2012, pp. 62–65.

- ↑ Bisson 1990, p. 285.

- ↑ Winterhager 2020, p. 261.

- ↑ Kats & Claszen 2012, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Kats & Claszen 2012, pp. 76–80.

- ↑ Kats & Claszen 2012, pp. 75–80.

- ↑ Kettemann 2000.

Bibliography

- Bisson, T. N. (1990). "Unheroed Pasts: History and Commemoration in South Frankland before the Albigensian Crusades". Speculum. 65 (2): 281–308. doi:10.2307/2864294.

- Buc, P. (2003). "Ritual and Interpretation: The Early Medieval Case". Early Medieval Europe. 9 (2): 183–210. doi:10.1111/1468-0254.00065.

- Bate, K. (2016). "Chronicon Anianense". In Graeme Dunphy; Cristian Bratu (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle. Brill.

- Kats, J. M. J. G.; Claszen, D. (2012). Chronicon Moissiacense Maius: A Carolingian World Chronicle From Creation until the First Years of Louis the Pious (MA thesis). Leiden University.

- Kettemann, W. (2000). Subsidia Anianensia: Überlieferungs und textgeschichtliche Untersuchungen zur Geschichte Witiza-Benedikts, seines Klosters Aniane und zur sogenannten "anianischen Reform" (PhD dissertation). University of Duisburg-Essen.

- Kramer, R. (2021). "A Crowning Achievement: Carolingian Imperial Identity in the Chronicon Moissiacense". In R. Kramer; H. Reimitz; G. Ward (eds.). Historiography and Identity III: Carolingian Approaches. Brepols. pp. 231–269. doi:10.1484/M.CELAMA-EB.5.120166.

- Winterhager, P. (2020). Migranten und Stadtgesellschaft im frühmittelalterlichen Rom: Griechischsprachige Einwanderer und ihre Nachkommen im diachronen Vergleich. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110678932.