| Antelope Canyon | |

|---|---|

| Tsé bighánílíní (in Navajo) | |

A beam of light in Upper Antelope Canyon (Hazdistazí) in Navajo | |

Antelope Canyon | |

| Floor elevation | 3,704 ft (1,129 m)[1] |

| Length | Upper Antelope Canyon: about 660 feet (200 m)[2] Lower Antelope Canyon: about 1,335 feet (407 m)[2] |

| Depth | about 120 feet (37 m)[3] |

| Geology | |

| Type | Sandstone slot canyon[3] |

| Age | 8-60 million years |

| Geography | |

| Population centers | Page |

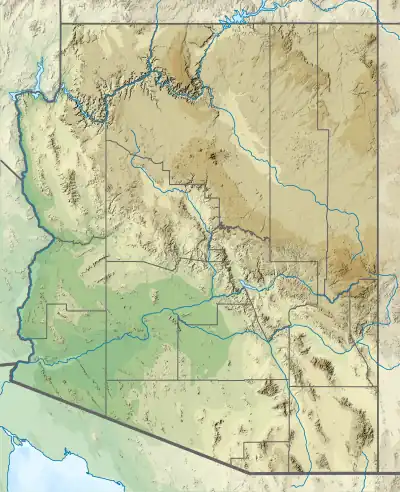

| Coordinates | 36°57′10″N 111°26′29″W / 36.9527664°N 111.4412683°W [1] |

| Topo map | USGS Page |

Navajo Upper Antelope Canyon is a slot canyon in the American Southwest, on Navajo land east of Lechee, Arizona. It includes six separate, scenic slot canyon sections on the Navajo Reservation, referred to as Upper Antelope Canyon (or The Crack), Rattle Snake Canyon, Owl Canyon, Mountain Sheep Canyon, Canyon X[4] and Lower Antelope Canyon (or The Corkscrew).[2] It is the primary attraction of Lake Powell Navajo Tribal Park, along with a hiking trail to Rainbow Bridge National Monument.

The Navajo name for Upper Antelope Canyon is Tsé bighánílíní, which means 'the place where water runs through the (Slot Canyon) rocks'. Lower Antelope Canyon is Hazdistazí (called "Hasdestwazi" by the Navajo Parks and Recreation Department), or 'spiral rock arches'. Both are in the LeChee Chapter of the Navajo Nation.[5] They are accessible by Navajo guided tour only.[6]

Geology

Antelope Canyon was formed by the erosion of Navajo Sandstone[2] due to flash flooding and other sub-aerial processes. Rainwater, especially during monsoon season, runs into the extensive basin above the slot canyon sections, picking up speed and sand as it rushes into the narrow passageways.[7] Over time the passageways eroded away, deepening the corridors and smoothing hard edges to form characteristic "flowing" shapes.[3]

Tourism and sightseeing

Antelope Canyon is a popular location for sightseers, and a source of tourism business for the Navajo Nation. It has been accessible by tour since 1983 by Pearl Begay Family and 1997, when the Navajo Tribe made it a Navajo Tribal Park. Besides the Upper and Lower areas, there are other slots in the canyon that can be visited, such as the Rattle Snake Canyon, Owl Canyon, and Mountain Sheep Canyon which is also part of the same drainage as Antelope Canyon.

Photography within the canyons is difficult due to the wide exposure range (often 10 EV or more) made by light reflecting off the canyon walls.[8]

Upper Antelope Canyon

Upper Antelope Canyon is called Tsé bighánílíní, 'the place where water runs through rocks' by the Navajo People in that specific area. It is the most frequently visited by tourists because its entrance and entire length are at ground level, requiring no climbing; and because beams of direct sunlight radiating down from openings at the top of the canyon are much more common all year round that make the inside canyon very colorful. Beams occur most often in the summer, as they require the sun to be high in the sky at midday. Light beams start to peek into the canyon on March 20 and disappear by October 20.

Lower Antelope Canyon

Lower Antelope Canyon, called Hazdistazí, or 'spiral rock arches' by the Navajo, is located several miles from Upper Antelope Canyon. Prior to the installation of metal stairways, visiting the canyon required climbing pre-installed ladders in certain areas.

Even following the installation of stairways, it is a more difficult hike than Upper Antelope. It is longer and narrower in places, and even footing is not available in all areas. Five flights of stairs of varying widths are currently available to aid in descent and ascent. At the end, the climb out requires flights of stairs. Additionally, sand continually falls from the crack above and can make the stairs slippery.[9]

Despite these limitations, Lower Antelope Canyon draws a considerable number of photographers, though casual sightseers are much less common than in the Upper Canyon. Photography-only tours are available around midday when light is at its peak. Photographers cannot bring a tripod.

The lower canyon is in the shape of a "V" and shallower than the Upper Antelope. Lighting is better in the early hours and late mornings.

Flash flooding

Antelope Canyon is visited exclusively through guided tours, in part because rains during monsoon season can quickly flood it. Rain does not have to fall on or near the Antelope Canyon slots for flash floods to whip through; rain falling dozens of miles away can funnel into them with little notice.[10]

On August 12, 1997, eleven tourists, including seven from France, one from the United Kingdom, one from Sweden and two from the United States, were killed in Lower Antelope Canyon by a flash flood.[11][12] Very little rain fell at the site that day, but an earlier thunderstorm dumped a large amount of water into the canyon basin 7 miles (11 km) upstream. The lone survivor was tour guide Francisco "Pancho" Quintana, who had prior swift-water training. At the time, the ladder system consisted of amateur-built wood ladders that were swept away by the flood. Today, ladder systems have been bolted in place, and deployable cargo nets are installed at the top of the canyon. A NOAA Weather Radio from the National Weather Service and an alarm horn are on hand at the fee booth.[13]

Despite improved warning and safety systems, the risks of injury from flash floods still exists. On July 30, 2010, several tourists were stranded on a ledge when two flash floods occurred at Upper Antelope Canyon.[14] Some of them were rescued and some had to wait for the flood waters to recede.[15] There were reports that a woman and her nine-year-old son were injured as they were washed away downstream, but no fatalities were reported.[16]

References

- 1 2 "Antelope Canyon". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. 27 June 1984. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Kelsey, Michael R. (2011). Non-Technical Canyon Hiking Guide to the Colorado Plateau (6th ed.). Provo, Utah: Kelsey Publishing. p. 324. ISBN 978-0944510278.

- 1 2 3 "Antelope Canyon: Overview". Navajo Tours. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ↑ Drier, Jess (2023-01-26). "Antelope Canyon X: Tips for Visiting in 2023". Unearth The Voyage. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- ↑ "Lake Powell Navajo Tribal Park". Navajo Nation Parks & Recreation. Archived from the original on 12 November 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- ↑ "Antelope Canyon Tour Operators". Navajo Nation Parks & Recreation. Retrieved 2022-03-08.

- ↑ "Antelope Canyon Geology". Navajo Tours. Archived from the original on 2015-02-09. Retrieved 2021-06-04.

- ↑ Martrès, Laurent (2006). A guide to the natural landmarks of Arizona. Sightsee the Southwest (2nd ed.). Alta Loma, CA: Graphie International. ISBN 978-0916189136.

- ↑ "Antelope Canyon Tour: Worth It!". The O'Briens Abroad, Family Vacations. 2017-10-22. Archived from the original on 2017-12-17. Retrieved 2017-12-16.

- ↑ "Lower Antelope Canyon – Where Surrealism meets Nature". Minor Sights. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ↑ "Flash Flood Antelope Canyon". Retrieved 20 March 2006.

- ↑ "Antelope Canyon". Archived from the original on 17 March 2006. Retrieved 20 March 2006.

- ↑ Kramer, Kelly (2008). "Man vs. Wild". Arizona Highways. 84 (11): 23.

- ↑ "Hikers rescued from flooding in northern Arizona canyon". ABC News. 1 August 2010. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ↑ "Eight People Rescued from Antelope Canyon". NAS Today. 30 July 2010. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ↑ "Five injured in Antelope Canyon flash flood". AZ Daily Sun. 1 August 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2013.