LGBT rights in Mexico | |

|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Status | Legal since 1871 |

| Gender identity | Transgender persons can change their legal gender and name in Mexico City and 18 states |

| Military | Ambiguous, LGBT soldiers are in a "legal limbo". Officially, there is no law or policy preventing them from serving, and applicants are not questioned on the subject. In practice, however, outed LGBT soldiers are subject to severe harassment and are often discharged. |

| Discrimination protections | Sexual orientation protection nationwide since 2003 (see below) |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | Same-sex marriage legal nationwide since 2022 |

| Adoption | Joint adoption legal in Mexico City and 21 states |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Mexico expanded in the 21st century, keeping with worldwide legal trends. The intellectual influence of the French Revolution and the brief French occupation of Mexico (1862–67) resulted in the adoption of the Napoleonic Code, which decriminalized same-sex sexual acts in 1871.[1] Laws against public immorality or indecency, however, have been used to prosecute persons who engage in them.[2][3]

Tolerance of sexual diversity in certain indigenous cultures is widespread, especially among Isthmus Zapotecs and Yucatán Mayas.[4][5][6] As the influence of foreign and domestic cultures (especially from more cosmopolitan areas such as Mexico City) grows throughout Mexico, attitudes are changing.[7] This is most marked in the largest metropolitan areas, such as Guadalajara, Monterrey, and Tijuana, where education and access to foreigners and foreign news media are greatest. Change is slower in the hinterlands, however, and even in large cities, discomfort with change often leads to backlashes.[8] Since the early 1970s, influenced by the United States gay liberation movement and the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre,[9] a substantial number of LGBT organizations have emerged. Visible and well-attended LGBT marches and pride parades have occurred in Mexico City since 1979, in Guadalajara since 1996, and in Monterrey since 2001.[10]

On 3 June 2015, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation released a "jurisprudential thesis" in which the legal definition of marriage was changed to encompass same-sex couples. Laws restricting marriage to a man and a woman were deemed unconstitutional by the court and thus every justice provider in the nation must validate same-sex unions. However, the process is lengthy as couples must request an injunction (Spanish: amparo) from a judge, a process that opposite-sex couples do not have to go through. The Supreme Court issued a similar ruling pertaining to same-sex adoptions in September 2016. While these two rulings did not directly strike down Mexico's same-sex marriage and adoption bans, they ordered every single judge in the country to rule in favor of same-sex couples seeking marriage and/or adoption rights. By 31 December 2022, every state had legalized same-sex marriage by legislation, executive order, or judicial ruling, though only twenty allowed those couples to adopt children. Additionally, civil unions are performed in the states of Campeche, Coahuila, Mexico City, Michoacán, Sinaloa Tlaxcala and Veracruz, both for same-sex and opposite-sex couples.

Political and legal gains have been made through the left-wing Party of the Democratic Revolution, leftist minor parties such as the Labor Party and Citizen's Movement, the centrist Institutional Revolutionary Party, and more recently the left-wing National Regeneration Movement. They include, among others, the 2011 amendment to Article 1 of the Federal Constitution to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation.[11][12]

History

Acceptance of homosexuality and transgender identities has been documented among various indigenous peoples of Mexico, most notably the Isthmus Zapotecs and Yucatán Mayas. The Isthmus Zapotecs recognize a traditional third gender, known as muxe, an intermediate between male and female. Muxes are assigned male at birth, but typically act and behave like women and do both women and men's work. Having a muxe in the family is perceived as good luck and a blessing.[13] They are often referred to as transgender in English language publications.

"Muxe, persons who appear to be predominantly male but display certain feminine characteristics are highly visible in Isthmus Zapotec populations. They fill a third gender role between men and women, taking some of the characteristics of both. Although they are perceived to be different from the general heterosexual male population, they are neither devalued nor discriminated against in their communities. Isthmus Zapotecs have been dominated by Roman Catholic ideology for more than four centuries. Mestizos, especially mestizo police, occasionally harass and even persecute muxe boys, but Zapotec parents, especially mothers and other women, are quick to defend them and their rights to "be themselves", because, as they put it, "God made them that way." I have never heard an Isthmus Zapotec suggest that a muxe chose to become a muxe. The idea of choosing gender or of choosing sexual orientation, the two of which are not distinguished by the Isthmus Zapotecs, is as ludicrous as suggesting, that one can choose one's skin color."

— Beverly Chiñas.[14]

Traditionally, Mayan society was relatively tolerant of homosexuality. There was a strong association between ritual and homosexual activity. Some shamans engaged in homosexual acts with their patients, and priests engaged in ritualized homosexual acts with their gods.[15] Similarly, the Toltecs were also "extremely sex tolerant", with public displays of sex and eroticism, including of homosexual acts.[16]

However, little is known about same-sex relationships in Aztec society. Some sources claim that homosexuality among young Aztec men was tolerated (homosexual acts were commonly practised in temples and before battle), but not among adult men, where the punishment could be death. The penetrated adult male (known as cuiloni) would typically be killed through anal impalement but the penetrating male would usually not suffer any punishments. On the other hand, many Aztec nobles and rich merchants had both male and female prostitutes and engaged in same-sex relations, and there were some religious rituals where homosexuality was acceptable, most notably Tezcatlipoca sacrifices. Intersex people (known as patlache) were regarded as "detestable women" by Aztec society and would be killed. However, some sources suggest that homosexuality was more widely practised and tolerated among the Aztecs and that most of the negativity surrounding the practice stems from Spanish records, as supposedly the Spanish had "huge problems trying to stamp out homosexuality". The Aztec god Xōchipilli is the patron of homosexuals and male prostitutes.[17]

1970 to present

During the early 1970s, influenced by the U.S. gay liberation movement and the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre,[9] small political and cultural groups were formed. Initially, they were strongly linked to the political left and, to a degree, feminist organizations. One of the first LGBT groups in Latin America was the Homosexual Liberation Front (Frente de Liberación Homosexual), organized in 1971 in response to the firing of a Sears employee because of his allegedly homosexual behavior in Mexico City.[18][19]

The Homosexual Front of Revolutionary Action (Frente Homosexual de Acción Revolucionaria) protested the 1983 roundups in Guadalajara, Jalisco.[18] The onset of AIDS during the mid-1980s created considerable debate and public discussion about homosexuality. Many voices, both supportive and opposing (such as the Roman Catholic Church), participated in public discussions that increased awareness and understanding of homosexuality. LGBT groups were instrumental in initiating programs to combat AIDS, which was a shift in focus that curtailed (at least temporarily) the emphasis on gay organizing.[19]

In 1991, Mexico hosted a meeting of the International Gay and Lesbian Association (ILGA), which was its first meeting outside Europe.[19] In 1997, LGBT activists were active in constructing the political platform that resulted in Patria Jiménez (a lesbian activist in Mexico City) being selected for proportional representation in the Chamber of Deputies representing the left-wing Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD).[19] LGBT rights advocate David Sánchez Camacho was also elected to the Legislative Assembly of the Federal District (ALDF).[20]

In August 1999, the First Meeting of Lesbians and Lesbian Feminists was held in Mexico City. From this meeting evolved an organized effort for expanded LGBT rights in the country's capital.[21] The following month, the PRD-controlled Legislative Assembly of the Federal District passed an ordinance banning discrimination based on sexual orientation, the first of its kind in Mexico.[22]

Visible (and well-attended) LGBT marches and pride parades have been held in Mexico City since 1979 and in Guadalajara since 1996, the country's largest cities.[19] In 2001, Article 1 of the Federal Constitution was amended to prohibit discrimination based (among other factors) on sexual orientation under the vague term preferences. On 11 June 2003, an anti-discrimination federal law took effect, creating a national council to enforce it.[23] The same year, Amaranta Gómez ran as the first transgender congresswoman candidate affiliated with the former Mexico Posible party.[24] In June 2011, the more precise term "sexual orientation" was inserted into Article 1 of the Constitution.

LGBT people in Mexico have organized in a variety of ways: through local organizations, marches, and the development of the Commission to Denounce Hate Crimes. Mexico has a thriving LGBT movement with organizations in various large cities throughout the country and numerous LGBT publications (most prominently in Mexico City, Guadalajara, Monterrey, Tijuana, and Puebla), the majority at the local level (since national efforts often disintegrate before gaining traction).[25]

Timeline of LGBT history in Mexico

- 1542: Hernan Cortés started his campaign in Cholula (now Cholula, Puebla). At that time, Amerindian homosexuality behavior varied from region to region. Cortés on behalf of his majesty the King of Spain started talking to the locals (hacer un parlamento, translated from old Spanish) and established rules against sodomy.[26]

- 1569: An official inquisition was created in Mexico City by Philip II of Spain. Same-sex sexual acts were a prime concern, and the Inquisition inflicted stiff fines, spiritual penances, public humiliations, and floggings for what it deemed to be sexual sins.[3]

- 1871: The intellectual influence of the French Revolution and the brief French occupation of Mexico (1862–67) resulted in the adoption of the Napoleonic Code. This meant that sexual conduct in private between adults (regardless of gender) ceased to be a criminal matter.[1][3]

- 1901: (20 November) Mexico City police raided an affluent drag ball, arresting 42 men (19 of which were cross-dressing). One was released, allegedly a close relative of President Porfirio Díaz. The resulting scandal, known as the "Dance of the 41 Maricones", received widespread press coverage.[1][3]

- 1959: Mayor Ernesto Uruchurtu closed all gay bars in Mexico City under the guise of "cleaning up vice" (or reducing its visibility).[9][18]

- 1971: The Homosexual Liberation Front (Frente de Liberación Homosexual), one of the first LGBT groups in Latin America, was organized in response to the firing of a Sears employee because of his (allegedly) homosexual orientation.[9][18]

- 1979: The country's first LGBT pride parade was held in Mexico City.[27]

- 1982: Max Mejía, Pedro Preciado, and Claudia Hinojosa became the first openly gay politicians to run unsuccessfully for seats in the Congress of Mexico.[28]

- 1991: Mexico hosted a meeting of the International Gay and Lesbian Association, the first meeting of the association outside Europe.[28]

- 1997: Patria Jiménez, a lesbian activist, was selected for proportional representation in the Chamber of Deputies of Mexico, representing the left-wing Party of the Democratic Revolution.[29]

- 1999: (August): The first meeting of lesbians and lesbian feminists was held in Mexico City. From this meeting, evolved an organized effort for expanded LGBT rights in the nation's capital.[28]

- (2 September): Mexico City passed an ordinance banning discrimination based on sexual orientation, the first of its kind in the country.[30]

- 2000: Enoé Uranga, an openly lesbian politician, proposed a bill that would have legalized civil unions in Mexico City. The local Legislature, however, decided not to enact the bill after widespread opposition from right-wing groups.[31]

- 2003: (29 April): A federal anti-discrimination law was passed and a national council was immediately created to enforce it.[32]

- (July): Amaranta Gómez became the first transgender woman to run unsuccessfully for a seat in the Congress of Mexico.[6]

- 2004: (13 March): Amendments to the Mexico City Civil Code that allow transgender people to change the gender and name on their birth certificates took effect.[33][34]

- 2006: (9 November): Mexico City legalized same-sex civil unions.[35]

- 2007: (11 January): The northern state of Coahuila legalized same-sex civil unions.[36]

- (31 January): The nation's first same-sex civil union ceremony was performed in Saltillo, Coahuila.[37]

- 2008: (September): The Mexico City Legislative Assembly passed a law, making it easier for transgender people to change their gender on their birth certificates.[38]

- 2009: (March): Miguel Galán, from the defunct Social Democratic Party, became the first openly gay politician to run unsuccessfully for mayor in the country.[39]

- (21 December): Mexico City's Legislative Assembly passed a bill legalizing same-sex marriage, adoption by same-sex couples, loan applications by same-sex couples, inheritance from a same-sex partner, and the sharing of insurance policies by same-sex couples.[40] Eight days later, Mayor Marcelo Ebrard signed the bill into law.[41]

- 2010: (4 March): The same-sex marriage law took effect in Mexico City.[42]

- (5 August): The Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation, the highest federal court in the country, voted 9–2 to uphold the constitutionality of Mexico City's same-sex marriage reform. Four days later, it upheld the city's adoption law.[43]

- 2011: (June): The Constitution of Mexico was amended to prohibit discrimination based on, among other factors, sexual orientation.[12]

- (24 November): The Coahuila Supreme Court struck down the state's law barring same-sex couples from adopting, urging the state's Legislature to amend the adoption law as soon as possible.[44]

- (28 November): Two same-sex couples were married in Kantunilkín, Quintana Roo, after discovering that Quintana Roo's Civil Code does not specify gender requirements for marriage.[45]

- 2012: (January): Same-sex marriages were suspended in Quintana Roo pending legal review by Luis González Flores, the Secretary of State of Quintana Roo.[46][47]

- (April): Roberto Borge Angulo, the Governor of Quintana Roo, annulled the two same-sex marriages performed in Kantunilkín.[46]

- (3 May): Luis González Flores reversed Borge Angulo's annulments in a decision allowing for future same-sex marriages to be performed in Quintana Roo.[48]

- (5 December): The Supreme Court struck down an Oaxaca state law that had limited marriage to one man and one woman for purposes of procreation.[49]

- 2013: (27 February): The first same-sex marriage licenses were issued in the state of Colima, after officials cited the Federal Constitution, which prohibits discrimination due to sexual orientation, and the Supreme Court ruling that struck down Oaxaca state's same-sex marriage ban.[50][51]

- (22 March): The first same-sex marriage occurred in Oaxaca.[52]

- (14 June): The Second Federal District Court of the State of Colima ruled that the State Civil Code was unconstitutional in limiting marriage to opposite-sex couples.[53]

- (1 July): The Third District Court of the State of Yucatán ruled that two petitioners were able to marry. Martha Góngora, director of the Civil Registry of the state, said the decision would be reviewed and might be returned to the court. Jorge Fernández Mendiburu, defense counsel in the case, indicated that if the registrar refused to complete the marriage, the case would be brought before the Supreme Court with a request for the state law limiting marriage to one man and one woman to be declared unconstitutional.[54][55]

- (4 July): The state of Colima amended its Constitution to allow for same-sex civil unions.[56]

- (8 August): Two men became the first same-sex couple to legally marry in the state of Yucatán.[57]

- (23 December): Campeche legalized same-sex and opposite-sex civil unions.[58]

- (11 February): The Congress of Coahuila legalized adoption by same-sex couples, by repealing Article 385-7 of the Civil Code.[60]

- (21 March): Mexico declared, by presidential decree, 17 May as the National Day Against Homophobia.[61] See also: "International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia and Transphobia".

- (1 September): The Congress of Coahuila legalized same-sex marriage, by changing the Civil Code of the state.[62]

- (13 November): The Legislative Assembly of Mexico City approved a gender identity law, making the process for transgender people to change gender much quicker and simpler.[63]

- 2015: (26 February): The Constitutional Court of the State of Yucatán announced that it will decide on 2 March whether state prohibitions against same-sex marriage are in violation of the Federal Constitution and international agreements.

- (2 March): The Constitutional Court of Yucatán dismissed the appeal for constitutional action to change the Civil Code. Supporters of amending the code promised to appeal the decision.

- (3 June): The Supreme Court released a "jurisprudential thesis" expanding the definition of marriage to encompass same-sex couples as state laws restricting it were deemed unconstitutional and discriminatory.[64]

- (12 June): The state of Chihuahua legalized same-sex marriage and adoption after the Governor announced that his administration would no longer oppose same-sex marriages within the state. The order was effective immediately.[65]

- (10 July): The Governor of Guerrero instructed civil agencies to approve same-sex marriage licenses.[66]

- (21 July): The municipality of Santiago de Querétaro stopped enforcing Querétaro's same-sex marriage ban and began allowing same-sex couples to marry in the municipality.[67]

- (11 August): The Mexican Supreme Court ruled, in a 9-1 decision, that Campeche's ban on same-sex couples adopting children was unconstitutional.[68]

- (7 September): The Congress of Michoacán legalized domestic partnerships for same-sex couples.[69]

- (22 December): Same-sex marriage became legal in the state of Nayarit.[70]

- 2016: (26 January): The Mexican Supreme Court unanimously struck down Jalisco's same-sex marriage ban.[71]

- (5 May): Colima repealed its civil union law as well as its constitutional ban on same-sex marriage.[72]

- (12 May): The Congress of Jalisco complied with the Supreme Court decision and instructed all the state's municipalities to issue same-sex marriage licenses.[73]

- (17 May): The Mexican President, Enrique Peña Nieto, announced that he had signed an initiative to amend Article 4 of the Mexican Constitution, which would legalize same-sex marriage nationwide.[74]

- (20 May): Same-sex marriage became legal in Campeche, after the state Congress legalized such marriages in a 34-1 vote 10 days prior.[75]

- (12 June): Same-sex marriage and adoption became legal in the state of Colima.[76]

- (23 June): A bill allowing for legal same-sex marriages and adoptions came into effect in Michoacán.[77]

- (5 July): A reform to the Constitution of Morelos, which legalized same-sex marriage and adoption in the state, took effect.[78]

- (11 September): The head of Veracruz's adoption agency announced that same-sex couples may adopt children jointly in the state.[79]

- (18 September): The municipality of San Pedro Cholula, located in the state of Puebla, announced that any same-sex couple who wishes to marry may do so in the municipality.[80]

- (23 September): The Mexican Supreme Court finalized the ruling in the adoption case against Campeche and issued a nationwide jurisprudence which binds all lower court judges to rule in favor of same-sex couples seeking adoption and parental rights.[81]

- (26 September): The state of Campeche lifted its same-sex adoption ban.[81]

- (22 February): The head of Baja California's adoption agency announced that same-sex couples have the right to adopt in the state.[83]

- (28 February) The Supreme Court gave Chihuahua 90 days to amend its Civil Code to reflect the recent legalization of same-sex marriage in the state.[84]

- (26 April): The head of Querétaro's adoption agency confirmed that same-sex couples may adopt in the state.[85]

- (31 May): The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal against the March 2015 Yucatán Constitutional Court ruling.[86]

- (11 July): The Supreme Court struck down Chiapas' same-sex marriage ban, legalizing same-sex marriage in the state.[87]

- (13 July): The Michoacán Congress approved a gender identity law.[88]

- (20 July): A gender identity law was approved in the state of Nayarit.[89]

- (1 August): The Supreme Court unanimously struck down Puebla's ban on same-sex marriage.[90]

- (3 November): The State Government of Baja California announced it would immediately cease to enforce its same-sex marriage ban, legalizing such marriages in the state.[91]

- 2018: (9 January): The Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled that same-sex marriage and the recognition of one's gender identity on official documents are human rights protected by the American Convention on Human Rights.[92] Mexico is a signatory to the Convention.

- (15 May): The Mexican Supreme Court ordered Sinaloa to legalize same-sex marriage within 90 days.[93]

- (1 July): The 2018 general elections resulted in the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA), a pro-same-sex marriage left-wing party, winning the majority or plurality of legislative seats in 13 states where same-sex marriage has not yet been legalized. MORENA along with the pro-same-sex marriage Labor Party also won an absolute majority in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate.[94][95]

- (1 July): President-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador became the first Mexican President to mention LGBT people in his first public speech. "The state will stop being a committee at the service of a minority and will represent all Mexicans: rich and poor, rural and urban dwellers, migrants, believers and non-believers, human beings of all currents of thought and of all sexual preferences. We will listen to everyone, we will attend to everyone. We will respect everyone, but we will give preference to the most humble and the forgotten, especially the indigenous peoples of Mexico", he said.[96]

- (26 August): The Civil Registry of Oaxaca began accepting applications for same-sex marriage licenses from throughout the state.[97][98][99]

- (13 September): Jalisco's civil union law was struck down on procedural grounds.[100]

- (17 October): The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the modification of a transgender person's birth certificate. In a ruling described as the first of its kind in Mexico, the court held that the person could change their name and gender marker on official documents through a simple administrative process, based solely on their own declaration of their gender identity.[101][102]

- (19 October): A Mexican federal court ruled that Mexico must recognize same-sex marriages performed in Mexican consulates and embassies abroad as long as one partner is a Mexican citizen.[103]

- (6 November): The Senate unanimously (110-0) passed a bill codifying certain court rulings pertaining to the legal rights of same-sex couples into law, namely social security benefits and the right to a widow or widower's pension.[104]

- (13 November): The state of Coahuila passed a gender identity bill, allowing transgender individuals easier access to birth certificates reflecting their new legal gender.[105]

- (16 November): The Supreme Court ordered the state of Tamaulipas to legalize same-sex marriage within 180 business days.[106]

- (28 November): The Chamber of Deputies approved the bill passed in the Senate earlier that month, in a unanimous 415-0 vote.[107]

- 2019: (14 February): Zacatecas City, the capital city of the state of Zacatecas, began issuing same-sex marriage licenses.[108]

- (19 February): Same-sex marriage became legal in the state of Nuevo León.[109][110]

- (2 April): Aguascalientes legalized same-sex marriage.[111][112]

- (25 April): The Hidalgo Congress approved a gender identity law.[113]

- (8 May): The Supreme Court of Mexico ruled that it is unconstitutional to deny a same-sex couple the right to register their children with the Civil Registry.[114][115]

- (11 May): The Mexican Supreme Court extended widow/widower's pensions to same-sex couples in concubinage.[116]

- (17 May): President Andrés Manuel López Obrador declared 17 May as the "National Day of Fighting Against Homophobia, Lesbophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia" (Spanish: Día Nacional de la Lucha contra la Homofobia, la Lesbofobia, la Transfobia y la Bifobia) and presented a series of actions that the Mexican Government will implement in support of the LGBT community, such as labor inclusion actions that guarantee opportunities regardless of sexual orientation and gender identity, joint work with teachers to eradicate discrimination and the implementation of protocol of action against hate crimes.[117][118]

- (17 May): The state of San Luis Potosí began authorizing legal gender changes for transgender people.[119]

- (21 May): Same-sex marriage became legal in San Luis Potosí, after the state Congress legalized such marriages in a 14-12 vote 5 days prior.[120][121]

- (11 June): Same-sex marriage became legal in Hidalgo, after the state Congress legalized such marriages in an 18-2 vote.[122]

- (29 June): Same-sex marriage became legal in the northern state of Baja California Sur.[123][124]

- (28 August): Same-sex marriage legislation passed the Congress of Oaxaca.[125][126][127]

Recognition of same-sex relationships

The United Mexican States is a federation composed of thirty-one states and a federal district, also known as Mexico City. Although a Federal Civil Code exists, each state has its own code that regulates concubinage and marriage. Civil unions and same-sex marriages are not recognized at the federal level. Most states, however, have considered legislation on these issues.[128]

In November 2013, Fernado Mayans, Senator for the state of Tabasco and representing the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), presented a proposal of changes to the Federal Civil Code in which marriage would be defined as "the free union of two people".[128] The proposal was turned over to the Justice, Legal Studies and Human Rights commissions in the Senate to be further studied.[129]

A provision in the Mexican Code allows that five rulings in a state with the same outcome on the same issue override a statute and establish the legal jurisprudence to overturn it. This means that if 5 injunctions (Spanish: amparo) are won in a state, the law has to be changed so that marriage becomes legal for all same-sex couples. It is also important to note that a same-sex marriage performed in any state is valid in all of the other states in Mexico, even if any particular state has no laws that allow it, according to federal law. Despite the legal requirement for the states to legalize same-sex marriage after 5 amparo rulings, this has often not been followed through. In Chihuahua, prior to the legalization of same-sex marriage there in 2015, almost 20 injunctions were carried out. Several states have simply chosen to ignore or delay the implementation of same-sex marriage, some times even at the cost of fines (in Tamaulipas legislators were fined for about 100 days due to their failure to legalize it).[130]

On 14 June 2015, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation declared it unconstitutional to deny marriage licenses to same-sex couples in all states. This did not legalize same-sex marriages nationwide, but in turn means that whenever a state government has an injunction taken out by a couple looking to get marital recognition, they will have to grant it and consider legalization when a certain number of injunctions is fulfilled.[131]

On 17 May 2016, the President of Mexico, Enrique Peña Nieto, signed an initiative to change the country's Constitution, which would have legalized same-sex marriage throughout Mexico pending congressional approval.[132] On 9 November 2016, the committee rejected the initiative 19 votes to 8.[133] However, legislation to allow same-sex marriage and adoption by same-sex couples is currently pending in almost every Mexican state.

The 2018 elections resulted in the National Regeneration Movement (MORENA) winning a majority or plurality of legislative seats in 13 states where same-sex marriage had yet to be legalized (Baja California Sur, Durango, Guerrero, Hidalgo, México, Oaxaca, San Luis Potosí, Sinaloa, Sonora, Tabasco, Tlaxcala, Veracruz and Zacatecas),[134] as well as an outright majority together with the Labor Party in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate, and the presidency. LGBT activists have since intensified their calls to legalize same-sex marriage at the federal and state levels.[94][95] Political parties supportive of same-sex marriage, including MORENA, the Labor Party, PRD and the Citizens' Movement, won a total of 303 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 81 seats in the Senate. In addition, supporters of same-sex marriage can be found in the remaining parties.

Mexico City

In 2000, Enoé Uranga, an openly lesbian politician and activist, proposed a bill legalizing same-sex civil unions in Mexico City under the name Ley de Sociedades de Convivencia (LSC).[135] The bill would have recognized the inheritance and pension rights of two adults, regardless of sexual orientation. Because of widespread opposition from right-wing groups and Mayor Andrés Manuel López Obrador's ambiguity concerning the bill, the Legislative Assembly decided not to consider it.[136] As new leftist Mayor Marcelo Ebrard was expected to take power in December 2006, the Legislative Assembly voted 43–17 to approve the LSC.[35] The law took effect on 16 March 2007.

On 24 November 2009, Assemblyman David Razú, a member of the Party of the Democratic Revolution, proposed a bill that would legalize same-sex marriage in Mexico City.[137] The bill was backed by the Human Rights Commission of Mexico City and over 600 non-governmental organizations, including the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, Amnesty International, and the AIDS Healthcare Foundation.[138][139] The National Action Party (PAN) announced it would either appeal the law in court or demand a referendum.[140]

The referendum proposal was rejected by the Legislative Assembly on a 36–22 vote on 18 December 2009.[141] On 21 December 2009, the Legislative Assembly passed the bill by a vote of 39–20 with five abstentions.[40] Eight days later, Mayor Marcelo Ebrard signed the bill into law.[41] It took effect on 4 March 2010.[42] The law changed the definition of marriage in the city's Civil Code to "a free union between two people". It also granted same-sex couples the right to adopt children.[142]

In February 2010, the Supreme Court rejected constitutional challenges by six states to the Mexico City law. The Federal Attorney General, however, had separately challenged the law as unconstitutional, citing an article in the Constitution of Mexico that refers to "protecting the family".[143] Five months later, the Supreme Court ruled 9–2 that the law did not violate the Constitution.[144]

Civil unions by state

On 11 January 2007, the Congress of the northern state of Coahuila legalized same-sex civil unions (by a 20–13 vote) under the name pacto civil de solidaridad (PCS), giving property and inheritance rights to same-sex couples.[145] The PCS was proposed by Congresswoman Julieta López of the centrist PRI, whose nineteen members voted for the law.[145][146] Luis Alberto Mendoza, deputy of the center-right PAN (which opposed), said the new law was an "attack against the family, which is society's natural group and is formed by a man and a woman".[145] Apart from that, the PCS drew little opposition and was notably supported by Bishop Raúl Vera.[146] Unlike Mexico City's law, once same-sex couples have registered in Coahuila, the state protects their rights (no matter where they live in Mexico).[146] Twenty days after the law passed, the country's first same-sex civil union took place in Saltillo, Coahuila.[37]

On 11 April 2013, the Party of the Democratic Revolution introduced a measure to legalize civil unions in Campeche.[147] The bill was unanimously passed on 20 December 2013, and while it covers both same-sex and opposite-sex couples, it specifically provides that it "shall not constitute a civil partnership of people living together in marriage and cohabitation." An additional distinction is that it is not filed with the Civil Registrar, but with the Public Registry of Property and Trade.[148]

In July 2013, the Congress of Colima approved a constitutional amendment authorizing same-sex couples to legally formalize their unions by entering into marital bonds with the "same rights and obligations with respect to the contracting of civil marriage".[149] On 5 May 2016, the civil union law was repealed in favor of same-sex marriage legislation.[72]

In 2013, deputies of the Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), Ecologist Green Party of Mexico (PVEM), Citizens' Movement (MC) and an independent deputy presented the Free Coexistence Act (Ley de Libre Convivencia) to the Congress of Jalisco.[150] The Act established that same-sex civil unions can be performed in the state, as long as they are not considered marriages. It did not legalize adoption and mandated that civil unions be performed with a civil law notary.[150][151] On 31 October 2013, the Jalisco Congress approved the Act in a 20–15 vote,[152] one abstained and three were absent.[151] The law took effect on 1 January 2014.[59] On 13 September 2018, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation struck down the law on procedural grounds.[100][153]

On 27 August 2015, the Justice and Human Rights Committee announced it would enact a civil union law for same-sex couples in Michoacán. It was approved unanimously in a 34-0 vote by the full Michoacán Congress on 7 September 2015.[69][154] The law was published on 30 September 2015 in the state's official journal.[155]

In December 2016, the Tlaxcala Congress approved a civil union bill, in an 18-4 vote. The bill went into effect on 12 January 2017.[82]

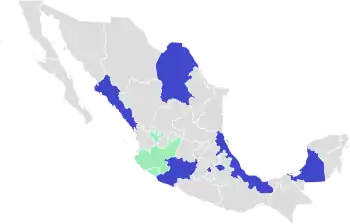

Same-sex marriage by state

The status of same-sex marriage in Mexico's states is complex. Currently, all states have legalized same-sex marriage. Previously, these marriages are recognized nationwide (even in states where same-sex couples could not marry) and by various federal departments and organizations. Same-sex marriage legalization has been achieved through different methods:

- [1] Legislative action (as has happened in Baja California Sur, Campeche, Coahuila, Colima, Guerrero, Hidalgo, Mexico, Mexico City, Michoacán, Morelos, Nayarit, Oaxaca, Queretaro, San Luis Potosí, Sinaloa, Tabasco, Tamaulipas, Tlaxcala, Yucatán and Zacatecas)

- [2] Administrative decision where the state Government or Civil Registry chose to stop enforcing its same-sex marriage ban (Baja California [later codified], Chihuahua, Durango [later codified], Quintana Roo [de facto codified] and Guanajuato)

- [3] Supreme Court ruling (Aguascalientes, Chiapas, Jalisco [later codified], Nuevo León [later codified], Puebla [later codified],Querétaro [later codified], Veracruz [later codified], and Zacatecas [later codified])

The Mexican Supreme Court has limited legal power. It cannot legalize same-sex marriage in the entire nation at once. It can, however, legalize it one state at a time and under specific circumstances, through the so-called "action of unconstitutionality" process. Through this process, the Supreme Court can directly strike down a state law, rendering it unenforceable and void (and thus ordering the state to license same-sex marriages). Actions of unconstitutionality can only be filed within 30 days after the law in question has gone into effect. In the case of the five states above, their local congresses modified their marriage laws, but left intact provisions outlawing same-sex marriages. LGBT groups subsequently filed actions with the Supreme Court. It is likely the state legislatures were unaware they were setting their bans for strike-down.

A fourth method exists. If officials in a given state repeatedly appeal amparo cases to a federal appeals court and lose five times in a row (note that since 2015 no court in Mexico is allowed to rule against same-sex marriage), and if the appellate court then forwards the results to the Supreme Court (SCJN), the SCJN can then force the state legislature to repeal its ban. It gives the state a deadline by which it must modify its laws, usually 90 or 180 business days. If the state fails to change its laws to allow same-sex marriage by that date, the court will issue a "General Declaration of Unconstitutionality" (Spanish: Declaratoria General de Inconstitucionalidad) and struck the law down. In these cases, the amparo is also called a "resolution". However, it is unlikely this process is as effective as the action of unconstitutionality process.

Timeline

On 28 November 2011, the first two same-sex marriages occurred in Quintana Roo after it was discovered that Quintana Roo's Civil Code did not explicitly prohibit same-sex marriage,[46] but these marriages were later annulled by the Governor of Quintana Roo in April 2012.[46] In May 2012, the Secretary of State of Quintana Roo reversed the annulments and allowed for future same-sex marriages to be performed in the state.[48]

Mexico's Supreme Court ruled in December 2012 that Oaxaca's marriage law was unconstitutional because it limited the ceremony to a man and a woman with the goal to "perpetuate the species".[156] In 2013, a lesbian couple became the first same-sex couple to marry after this ruling.[156] The ruling did not legalize same-sex marriage in the state, however, but rather created jurisprudence against same-sex marriage bans.

On 11 February 2014, the Congress of Coahuila approved adoptions by same-sex couples and a bill legalizing same-sex marriages passed on 1 September 2014, making Coahuila the second jurisdiction in Mexico to reform its Civil Code to allow for legal same-sex marriages.[60][62] It took effect on 17 September, and the first couple married on 20 September.[157]

On 12 June 2015, the Governor of Chihuahua announced that his administration would no longer oppose same-sex marriages within the state. The order was effective immediately, thus making Chihuahua the third state to legalize such unions.[65]

On 25 June 2015, following the Supreme Court's ruling, a civil registrar in Guerrero announced that they had planned a collective same-sex marriage ceremony for 10 July 2015 and indicated that there would have to be a change to the law to allow gender-neutral marriage, passed through the state Congress before the official commencement.[66] The registry announced more details of their plan, advising that only select registration offices in the state would be able to participate in the collective marriage event.[158] The Governor instructed civil agencies to approve same-sex marriage licenses. On 10 July 2015, 20 same-sex couples were married by Governor Rogelio Ortega Martínez in Acapulco.[159] However, not all municipalities in the state perform same-sex marriages.[160]

On 17 December 2015, the Congress of Nayarit approved a bill legalizing same-sex marriage.[70] In January 2016, the Mexican Supreme Court declared Jalisco's Civil Code unconstitutional for limiting marriage to opposite-sex couples, effectively legalizing same-sex marriage in the state. Although the ruling was officially published in the Official Gazette of the Federation (Diario Oficial de la Federación) on 21 April 2016 and took effect on that date, several municipalities had already begun issuing same-sex marriage licenses, including Puerto Vallarta, Guadalajara and Tlaquepaque. On 12 May 2016, the Congress of Jalisco officially instructed all the state's municipalities to issue same-sex marriage certificates,[71] but did not amend its Civil Code to be in compliance with the ruling until 6 April 2022. On 10 May 2016, the Congress of Campeche passed a same-sex marriage bill.[75] On 18 May 2016, both Michoacán and Morelos passed bills allowing for same-sex marriage to be legal.[77] On 25 May 2016, a bill to legalize same-sex marriage in Colima was approved by the state Congress.[76]

In fourth separate actions of unconstitutionality, the Mexican Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage in Chiapas on 11 July 2017,[87] in Puebla on 1 August 2017,[90] in Nuevo León on 19 February 2019,[109][110] and in Aguascalientes on 2 April 2019.[111] These rulings went into force upon publication in the Diario Oficial de la Federación. Chiapas' ruling was published on 11 May 2018, but the local Civil Registry had already started issuing same-sex marriage licenses, beginning on 30 October 2017.[161] Puebla's and Nuevo León's rulings were published on 16 February 2018 and 31 May 2019, respectively. The Congress of Puebla amended its Civil Code in compliance with the ruling in November 2020.

On 3 November 2017, the State Government of Baja California announced it would cease to enforce its same-sex marriage ban,[91] and instructed civil registrars to begin issuing marriage certificates to same-sex couples. The Congress of Baja California would later codify the decision into law and the state constitution in June 2021. Similarly, in the southern state of Oaxaca, the local Civil Registry announced in August 2018 that it would accept applications for same-sex marriage licenses from throughout the state, and the state congress later amended the civil code to permit same-sex marriage in August 2019.[97][98][99]

On 21 May 2019, same-sex marriage became legal in San Luis Potosí, after the state Congress legalized such marriages in a 14-12 vote 5 days prior.[120][121] A same-sex marriage law in the state of Hidalgo was approved on 14 May 2019, and took effect on 11 June. Likewise, a same-sex marriage bill was approved in Baja California Sur on 27 June 2019, and came into force two days later.[123][124]

The Congress of Tlaxcala passed a law allowing same-sex marriage on 8 December 2020. Same-sex marriage was also approved by the Congress of Sinaloa on 15 June 2021 and in Zacatecas later that year. The Congress of Yucatán passed a constitutional amendment allowing same-sex marriage on 7 September 2021 and amended secondary legislation to permit it on 1 March 2022. The Congress of Veracruz passed a law allowing same-sex marriage on 2 June 2022, three days after the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation struck down a law forbidding it.[162] The Governor of Durango issued a decree legalizing same-sex marriage in the state on 18 September 2022.[163] The Congress of the State of Mexico passed a law allowing same-sex marriage and concubinage on 11 October 2022.[164] The Congress of the state of Guerrero passed a law allowing same-sex marriage and concubinage on 25 October 2022.[165] The Congress of the state of Tamaulipas passed a same-sex marriage law on 26 October 2022; it was the final state to legalize same-sex marriage.[166]

Adoption and family planning

Married same-sex couples are not allowed to adopt children in every state in Mexico, despite married couples being allowed to adopt. Mexico City, along with the states of Aguascalientes, Baja California, Baja California Sur, Campeche, Chiapas, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Colima, Hidalgo, Jalisco, Michoacán, Morelos, Nayarit, Nuevo León, Puebla, Querétaro, Quintana Roo, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas,[167] and Veracruz allow for same-sex couples to adopt children jointly. The law does not specifically bar same-sex couples from adopting in Durango, but none has as of June 2022.[168]

Mexico City legalized same-sex adoptions in March 2010, when its same-sex marriage law took effect.[40] On 24 November 2011, the Coahuila Supreme Court struck down the state's law barring same-sex couples from adopting.[44] The state complied with the ruling in February 2014 and legalized such adoptions.[60] According to the Chihuahua National System for Integral Family Development, the Office of the Defense of Children and the Family in the state performs the same protocol for all couples seeking to adopt regardless of their sexual orientation.[169]

On 11 August 2015, the Mexican Supreme Court ruled, in a 9-1 decision, that Campeche's ban on same-sex couples adopting children was unconstitutional.[68] The Supreme Court struck down Article 19 of Campeche's civil union law which outlawed adoption by couples in civil unions. Children's rights were cited as the main reason for the Court's decision. The ruling set a constitutional precedent, meaning all bans in Mexico forbidding same-sex couples from adopting are unconstitutional and discriminatory. On 23 September 2016, the Mexican Supreme Court finalized the ruling in the adoption case against Campeche and issued a nationwide jurisprudence which binds all lower court judges to rule in favor of same-sex couples seeking adoption and parental rights.[81] Campeche lifted its adoption ban three days later.[81]

Colima, Michoacán and Morelos legalized such adoptions following the approval of their respective same-sex marriage laws in May 2016.[76][77][78] In September 2016, the head of Veracruz's adoption agency announced that same-sex couples may adopt children jointly in the state.[79] In February 2017 and April 2017, the heads of Baja California's and Querétaro's adoption agencies made similar statements, confirming that same-sex couples are allowed to legally adopt in their respective states.[83][85] Following the Supreme Court's ruling which struck down Chiapas' same-sex marriage ban, officials from the state confirmed that same-sex couples are allowed to adopt, like married opposite-sex couples.[170] Puebla officials similarly confirmed that same-sex couples are allowed to adopt, after the August 2017 Supreme Court ruling striking down Puebla's marriage ban.[171]

In early 2018, the president of the Supreme Court of Aguascalientes, Juan Manuel Ponce Sánchez, stated that no law prohibits same-sex couples from adopting in Aguascalientes. His statement was echoed by several deputies and government officials.[172]

In May 2019, in a unanimous ruling, the Mexican Supreme Court ruled that it is unconstitutional to deny a same-sex couple the right to register their children with the Civil Registry. In this particular case, which originated in Aguascalientes, a lesbian couple had applied in 2015 to register their newborn child with both the mothers' surnames, which the Civil Registry refused to do. The Supreme Court held that the refusal violated the "fundamental rights of equality and non-discrimination, the right of the identity of minors and the principle of their interest, as well as the right to protection of the organization and development of the family."[173]

Adoption by same-sex couples became legal in San Luis Potosí and Hidalgo in May and June 2019, following the approval of same-sex marriage.[174][175] Same-sex couples may also adopt in Jalisco[176] and Nuevo León.[177] Adoption by same-sex couples in Quintana Roo was legalized by the state congress in August 2022[178] and in Baja California Sur in November 2022.[179]

Discrimination protections

On 29 April 2003, the Federal Congress unanimously passed the Federal Law to Prevent and Eliminate Discrimination (Spanish: Ley Federal para Prevenir y Eliminar la Discriminación), including sexual orientation as a protected category. The law, which went into effect on 11 June 2003, created the National Council to Prevent Discrimination (Consejo Nacional para Prevenir La Discriminación, CONAPRED) to enforce it.[180] Mexico became the second country in Latin America, after Ecuador, to provide anti-discrimination protection for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people.[180] Article 4 of the law defines discrimination as:

"Every distinction, exclusion or restriction based on ethnic or national origin, sex, age, disability, social or economic status, health, pregnancy, language, religion, opinion, sexual preferences, civil status or any other, that impedes recognition or enjoyment or rights and real equality in terms of opportunities for people."

— Article 4 of the Federal Law to Prevent and Eliminate Discrimination[180]

Article 9 defines "discriminatory behavior" as:

"Impeding access to public or private education; prohibiting free choice of employment, restricting access, permanency or promotion in employment; denying or restricting information on reproductive rights; denying medical services; impeding participation in civil, political or any other kind of organizations; impeding the exercise of property rights; offending, ridiculing or promoting violence through messages and images displayed in communications media; impeding access to social security and its benefits; impeding access to any public service or private institution providing services to the public; limiting freedom of movement; exploiting or treating in an abusive or degrading way; restricting participation in sports, recreation or cultural activities; incitement to hatred, violence, rejection, ridicule, defamation, slander, persecution or exclusion; promoting or indulging in physical or psychological abuse based on physical appearance or dress, talk, mannerisms or for openly acknowledging one's sexual preferences."

— Article 9 of the Federal Law to Prevent and Eliminate Discrimination[180]

CONAPRED is an organ of the state created by Federal Law to Prevent and Eliminate Discrimination, adopted on 29 April 2003, and published in the Official Journal of the Federation (Diario Oficial de la Federación) on 11 June. The Council is the leading institution for promoting policies and measures contributing to cultural development and social progress in social inclusion and the right to equality, which is the first fundamental right in the Federal Constitution.[23]

CONAPRED is also responsible for receiving and resolving grievances and complaints of alleged discriminatory acts committed by private individuals or federal authorities in carrying out their duties. CONAPRED also protects citizens with any distinction (or exclusion), based on any aspect mentioned in Article 4 of the federal law.[23] The Council has legal personality, owns property, and is part of the Interior Ministry. Technical and management decisions are independent for its resolutions on claims and complaints.[23]

2011 constitutional amendment

In 2011, the Mexican Constitution was amended to prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.[11][12] An amendment to the Constitution requires ratification by at least 16 states. The states of Aguascalientes, Baja California Sur, Campeche, Chiapas, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Colima, Durango, Guerrero, México, Michoacán, Nayarit, Querétaro, Quintana Roo, San Luis Potosí, Sonora, Tabasco, Tamaulipas, Veracruz, Yucatán and Zacatecas subsequently ratified the amendment.[12] Article 1 of the Constitution reads:

Any form of discrimination, based on ethnic or national origin, gender, age, disabilities, social status, medical conditions, religion, opinions, sexual orientation, marital status, or any other form, which violates the human dignity or seeks to annul or diminish the rights and freedoms of the people, is prohibited.

— Constitution of Mexico

State-level laws

Most of Mexico's states have enacted laws that ban discrimination based on sexual orientation or sexual preference, as well as gender. Many states also explicitly ban discrimination based on gender identity in local laws.

Bans discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity

Aguascalientes,[181] Baja California,[182] Baja California Sur,[183] Campeche,[184] Coahuila,[185] Durango,[186] Guerrero,[187] Hidalgo,[188] Jalisco,[189] Mexico City,[190] Michoacan,[191] Morelos,[192] Nayarit,[193] Nuevo León,[194] Oaxaca,[195] Puebla,[196] Quintana Roo,[197] Sinaloa,[198] Sonora,[199] Tlaxcala,[200] and Yucatán.[201]

Bans discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender, but not gender identity

Chiapas,[202] Chihuahua,[203] Colima,[204] Guanajuato,[205] Queretaro,[206] San Luis Potosi,[207] Tabasco,[208] Tamaulipas,[209] Veracruz,[210] and Zacatecas.[211]

Does not explicitly ban sexual orientation or gender identity discrimination in local law

State of Mexico[212]

Hate crime laws

Hate crimes laws that recognize motivation by gender and sexual preferences have been passed in Mexico City and in the states of Aguascalientes, Baja California,[213] Baja California Sur, Campeche,[214] Colima, Coahuila, Guerrero, Jalisco, Michoacán, Nayarit, Nuevo Leon,[215] Oaxaca,[216] Puebla, Querétaro, Quintana Roo,[217] San Luis Potosí, Sinaloa, Sonora,[218] Tlaxcala,[219] Veracruz and Zacatecas.[220]

LGBT speech laws

Mexico's Supreme Court ruled in 2013 that two anti-gay slurs, "puñal" and "maricones," are not protected as freedom of expression under the Constitution, allowing people offended by the terms to sue for moral damages.[221]

Military service

The Mexican Armed Forces' policy on sexual orientation is ambiguous, leaving homosexual and bisexual soldiers in a "legal limbo". Officially, there is no law or policy preventing homosexuals from serving, and applicants are not questioned on the subject. In practice, however, outed homosexual and bisexual soldiers are subject to severe harassment and are often discharged. One directive, issued in 2003, described actions "contrary to morality or good manners on- and off-duty" (Spanish: en contra de la moral o de las buenas costumbres dentro y fuera del servicio [sic]) as serious misconduct warranting disciplinary action. Other references to morality are found throughout military documents, leaving room for interpretation with regards to sexual orientation. Although there is no clear position from current military leadership, several retired generals have agreed that homosexual soldiers were usually removed from service either through an encouraged withdrawal or dishonorable discharge.[222][223] By 2018, homosexuals were allowed to serve openly in the military.[224] People whose homosexuality is discovered face harassment from other soldiers.[225]

In 2007, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation ruled that it is unconstitutional to discharge soldiers for being HIV-positive. Previously, a 2003 law required that HIV-soldiers be discharged from service.[225]

Gender identity and expression

On 13 March 2004, amendments to the Mexico City Civil Code to allow transgender people to change their gender and name on their birth certificates took effect.[33][34] In September 2008, the PRD-controlled Mexico City Legislative Assembly approved a further law, in a 37-17 vote, making gender changes easier for transgender people.[38]

On 13 November 2014, the Legislative Assembly of Mexico City unanimously (46-0) approved a gender identity law. The law makes it easier for transgender people to change their legal gender.[63] Under the new law, they simply have to notify the Civil Registry that they wish to change the gender information on their birth certificates. Sex reassignment surgery, psychological therapies or any other type of diagnosis are no longer required. The law took effect in early 2015. By late 2018, 3,481 transgender people (2,388 trans women and 1,093 trans men) had taken advantage of the law.[226]

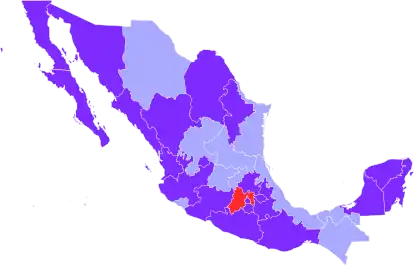

As of 2023, twenty states have followed suit: Michoacán (2017),[88] Nayarit (2017),[89] Coahuila (2018),[105] Hidalgo (2019),[113] San Luis Potosí (2019),[119] Colima (2019),[227] Baja California (2019),[228][229] Oaxaca (2019),[230] Tlaxcala (2019),[231] Chihuahua (2019),[232] Sonora (2020),[233] Jalisco (2020 [codified in 2022]),[234][235] Quintana Roo (2020),[236] Puebla (2021),[237] Baja California Sur (2021)[238] the State of Mexico (2021),[239] Morelos (2021), Sinaloa (2022),[240] Zacatecas (2022),[241] and Durango (2023).[242]

In August 2018, a federal judge in Tamaulipas ordered the modification of transgender women's birth certificates.[243] In October 2018, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation held that forbidding transgender people from changing their legal gender on official documents is a violation of constitutional rights, in a case of a transgender person from Veracruz who was denied recognition of their legal name and gender.[101][102] Likewise, it ruled in May 2019 that the right to self-determination of gender identity is a fundamental human right. This case involved a transgender person from Jalisco who was denied the right to change their legal gender.[244][245]

In February 2022, Mexico issued the first non-binary gender marker on a birth certificate by a court ruling.[246] In July 2022, Mexican Secretariat of the Interior issued the first non-binary Personal ID code by a court ruling. [247] In November 2022, the Hidalgo state congress voted unanimously to recognize non-binary gender identity.[248]

Passports

Implemented in May 2023, Mexico Passports explicitly include male, female and X available options. Same as Passports within both Canada and the United States.[249][250]

Conversion therapy

As of 2022, a bill to ban the pseudoscientific practice and foresee punishments of up to twelve years imprisonment for anyone practicing or promoting it is pending in the Mexican Congress. On 11 October 2022, the Mexican Senate passed the bill in a 69-16 vote. The bill was then sent to the Chamber of Deputies.[251]

Eighteen states have passed local bans on conversion therapies.

- Mexico City (31 July 2020)[252]

- State of Mexico (20 October 2020)[253]

- Baja California Sur (28 June 2021)

- Yucatán (25 August 2021)

- Zacatecas (25 August 2021)[254][220]

- Colima (28 September 2021)[255]

- Tlaxcala (19 October 2021)[256]

- Oaxaca (11 November 2021)[257]

- Jalisco (6 April 2022)[258]

- Baja California (26 May 2022)[259]

- Puebla (2 June 2022)[260]

- Hidalgo (7 June 2022)[261]

- Sonora (6 December 2022)[262]

- Nuevo León (21 December 2022)[263]

- Querétaro (29 June 2023)[264]

- Sinaloa (27 July 2023)[265]

- Morelos (15 December 2023)[266]

- Quintana Roo (15 December 2023)[266]

Blood donation

In August 2012, new health regulations allowing for gay and bisexual men to donate blood were approved. The regulations were published in the country's regulatory diary in October and took effect on Christmas Day, 25 December 2012.[267]

Public opinion

A 2020 Pew Research Center opinion survey showed that 69% of Mexicans believed homosexuality should be accepted by society up from 61% in 2013.[268][269] Younger people were more accepting than people over 50: 82% of people between 18 and 29 believed it should be accepted, 72% of people between 30 and 49 and 53% of people over 50.[269]

In May 2015, PlanetRomeo, an LGBT social network, published its first Gay Happiness Index (GHI). Gay men from over 120 countries and territories were asked about how they feel about society's view on homosexuality, how do they experience the way they are treated by other people and how satisfied are they with their lives. Mexico was ranked 32, just above Portugal and below Curaçao, with a GHI score of 56.[270]

Following President Enrique Peña Nieto's proposal to legalize same-sex marriage in Mexico, a poll on the issue was carried out by Gabinete de Comunicación Estratégica. 69% of respondents were in favor of the change. 64% said they saw it as an advance in the recognition of human rights. Public opinion changed radically over the course of 16 years. In 2000, 62% felt that same-sex marriage should not be allowed under any circumstances. In 2016, only 25% felt that way.[7]

Living conditions

According to the first National Poll on Discrimination (2005) in Mexico (conducted by the CONAPRED), 48 percent of the Mexican people interviewed indicated that they would not permit a homosexual to live in their house.[271] 95 percent of gays interviewed indicated that in Mexico there was discrimination against them; four out of ten declared they were a victim of exclusionary acts; more than half said they felt rejected, and six out of ten felt their worst enemy was society.[271]

LGBT social life thrives in the country's largest cities and resorts. The center of the Mexico City LGBT community is the Zona Rosa, where over 50 gay bars and dance clubs exist.[272] Surrounding the nation's capital, there is a substantial LGBT culture in the State of Mexico.[273] Although some observers claim that gay life is more developed in Mexico's second-largest city, Guadalajara.[18]

Other centers include border city Tijuana,[274] northern city Monterrey,[275] central cities Puebla,[276] and León,[277] and major port city Veracruz.[278] The popularity of gay tourism (especially in Puerto Vallarta, Cancún, and elsewhere) has also drawn national attention to the presence of homosexuality in Mexico.[279] Among young, urban heterosexuals, it has become popular to attend gay dance clubs and to have openly gay friends.[279]

In 1979, the country's first LGBT Pride parade (also known as the LGBT Pride March) was held in Mexico City and was attended by over 1,000 people.[280] Ever since, the parade has been held each June with different themes. It aims to bring visibility to sexual minorities, raise consciousness about AIDS and HIV, denounce homophobia, and demand the creation of public policies such as the recognition of civil unions, same-sex marriages, and the legalization of LGBT adoption.[281] According to organizers, the XXXI LGBT Pride parade in 2009 was attended by over 350,000 people (100,000 more than its predecessor).[282] Attendance was 500,000 in 2010,[283] and 250,000 in 2018.[284]

In 2003, the first Lesbian Pride March was held in the nation's capital.[285] In Guadalajara, well-attended LGBT Pride parades have also been held each June since 1996.[286] Tijuana,[287] Puebla,[288] Veracruz,[289] Xalapa,[290] Cuernavaca,[291] Tuxtla Gutiérrez,[292] Acapulco,[293] Chilpancingo,[289] and Mérida also host a variety of pride parades and events.[294]

LGBT tourism

In May 2019, the National Association of Commerce and Tourism LGBT of Mexico (Cancotur) revealed that LGBT-related tourism in Mexico has been growing steadily, up to 8% each year, and that the most "gay-friendly" destinations in the country were Mexico City, Puerto Vallarta, Cancún, Oaxaca, Puebla, Coahuila and Morelos.[295][296]

Anti-LGBT violence

Same-sex sexual acts are legal in Mexico, but LGBT people have been prosecuted through the use of legal codes that regulate obscene or lurid behavior (atentados a la moral y las buenas costumbres). Over the past twenty years, there have been reports of violence against gay men, including the murders of openly gay men in Mexico City and of transgender people in the southern state of Chiapas. Local activists believe that these cases often remain unsolved, blaming the police for a lack of interest in investigating them and for assuming that gays are somehow responsible for attacks against them.[19]

In mid-2007, Emilio Alvarez Icaza Longoria (chairman of the Human Rights Commission of Mexico City) said he was deeply concerned that Mexico City had the worst record for homophobic hate crimes, with 137 such crimes reported between 1995 and 2005.[271] Journalist and author Fernando del Collado (Homophobia, Hate, Crime and Justice 1995–2005) affirmed that during the decade covered by his book, 387 hate crimes due to homophobia were committed in Mexico (98 percent of which remained unprosecuted).[271]

Del Collado expressed his concern about a lack of prosecution and reported that according to the Citizens Commission Against Hate Crime because of Homophobia (CCCOH), three gays are murdered per month in Mexico.[271] Del Collado indicated that between 1995 and 2005, 126 gays were murdered in Mexico City. Of those, 75 percent were reclaimed by their families. In 10 percent of the cases, families identified the victim but did not reclaim their bodies (which were buried in common graves) and the remaining 5 percent were never identified.[271]

Former assistant attorney for crime victims at the Federal District Attorney General's Office (PGJDF) Barbara Illan Rondero strongly criticized the lack of sensitivity and professionalism on the part of investigators in crimes committed against gays and lesbians:

"I still can't determine if this is due to negligence, lack of preparation or down-right covering up and is a matter that has to do with the intention of not solving these crimes because they carry no weight of importance".[271]

Alejandro Brito Lemus, director of the news supplement Letra S ("Letter S"), claimed in 2007 that only four percent of gays and lesbians who suffer from discrimination present their complaints to authorities:

"In spite of the gravity of the aggressions suffered, the majority of gays, lesbians and transsexuals prefer to keep silent about what happens and to remain isolated in fear of being attacked again in revealing their sexual orientation".[271]

Political influence

LGBT participation is a part of the long-governing Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Since the triumph of the Liberals under President Benito Juárez in the 1860s and the 1910 Revolution, there has been separation of church and state in Mexico. With morality generally considered the province of the Church, the PRI (which considers itself the party of the Revolution) has generally been reluctant to be seen as implementing the will of the Catholic Church. However, it has also been careful not to offend Catholic moral sensibilities.[297] Nevertheless, most individual officeholders tend to view LGBT issues as a private matter (to be ignored) or a moral problem (to be opposed). The PRI has allied with the PAN to block legislation concerning LGBT rights in some states (except in some cases). The party unanimously voted in favor of the recognition of same-sex civil unions in Mexico City and Coahuila, for instance.[136][145] There was some internal debate within the PRI whether or not the party should have a platform plank on the issue.

The National Action Party (PAN), a rightist party, tends to endorse Roman Catholic Church teachings and oppose LGBT issues on moral grounds. Some PAN mayors have adopted ordinances (or policies) leading to the closing of gay bars or the detention of transvestites (usually on prostitution charges).[297] Many of its leaders have taken public stands describing homosexuality as "abnormal", a "sickness", or a "moral weakness".[297] Nevertheless, in Campeche and Nayarit, PAN deputies voted unanimously to legalize same-sex marriage.

In the 2000 presidential elections, PAN candidate (and eventual winner) Vicente Fox used homosexual stereotypes to demean and humiliate his principal opponent (Francisco Labastida). Fox accused Labastida of being a sissy and a mama's boy and nicknamed him Lavestida ("the cross-dressed").[298] When Mexico City and Coahuila legalized same-sex civil unions, the chief opposition came from the PAN, former President Vicente Fox and former President Felipe Calderón. Since then, the party has opposed similar bills, with the rationale of protecting traditional family values.[299] Nonetheless, PAN officials have insisted that homosexuals have rights as human beings and should in no case be subjected to hatred or physical violence.[297]

Participation by sexual minorities is widely accepted in the left-wing Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD), one of Mexico's three major political parties. Since its creation during the late 1980s, the PRD has supported LGBT rights and has a party program committed to ending discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.[300] In the 1997 parliamentary elections, Patria Jiménez became the first openly lesbian member of the Federal Congress, and LGBT rights advocate David Sánchez Camacho was elected to the Legislative Assembly of the Federal District (ALDF).[20]

Two years later, the PRD-controlled Legislative Assembly of the Federal District passed an ordinance banning discrimination based on sexual orientation (the first of its kind in the country).[22] In 2004, a bill concerning gender identity was passed, allowing transgender people to change their gender and sex on official documents.[33] In the 2009 parliamentary elections, of the 38 LGBT candidates presented by several political parties, only Enoé Uranga succeeded:[301] an openly lesbian politician who, in 2000, promoted the legalization of same-sex civil unions in Mexico City.[135] The bill passed six years later in the PRD-controlled Legislative Assembly, allowing same-sex couples inheritance and pension rights. Similar bills have been proposed by the PRD in many more states.

Other leftist, smaller parties such as the Citizens' Movement and the Labor Party (PT), have supported the LGBT community and PRD-proposed bills regarding LGBT rights.[302]

The defunct Social Democratic Party (PSD), a minor progressive party, was noted for its support of the LGBT community. In the 2006 presidential elections, Patricia Mercado, the first woman presidential candidate, was the only candidate openly supporting same-sex marriage.[303] In the 2009 parliamentary elections, the party nominated 32 LGBT candidates (out of a total of 38 presented by other parties) for seats in the Federal Congress.[301]

In the municipality of Guadalajara, the second-largest city of Mexico, Miguel Galán became the first openly gay politician to run for mayor in the country.[135] During his campaign, Galán was a target of homophobic comments, notably by Green Party rival Gamaliel Ramírez (who, on a radio show, joked about homosexuals and referred to the PSD as "a dirty party of degenerates"). Ramírez also called homosexual practices "abnormal" and said they should be outlawed. The following day, Ramírez issued a written apology after his party condemned his comments.[304] Despite losing the election, Galán received 7,122 votes.[301]

HIV/AIDS

The first AIDS case in Mexico was diagnosed in 1983.[305] Based on retrospective analyses and other public-health investigative techniques, HIV in Mexico may be traced back to 1981.[306] LGBT groups were instrumental in initiating programs to combat AIDS—a shift in focus which curtailed (at least temporarily) an emphasis on gay organizing.[19]

The National Center for the Prevention and Control of HIV/AIDS (CENSIDA) is a program promoting prevention and control of the AIDS pandemic with public policies, promotion of sexual health, and other evidence-based strategies. It aims to diminish the transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and sexually transmitted diseases and to improve the quality of life of affected people (within a framework of the common good).[307] CENSIDA has been active since 1988 and collaborates with other government agencies and non-governmental organizations (including those for persons living with HIV/AIDS).[308]

According to a 2011 estimate, 0.2 percent of persons aged 15–49 were HIV-positive, which along with Cuba and Nicaragua was the lowest rate in Latin America and the Caribbean.[309] In absolute numbers, an estimated 180,000 people in Mexico were living with HIV in 2011, the second-largest affected population in the region after Brazil.[309] According to CENSIDA, as of 2009, over 220,000 adults are HIV-positive; 60 percent are men who have sex with men, 23 percent are heterosexual women and 6 percent are commercial sex workers' clients (mainly heterosexuals).[310] Over 90 percent of the reported cases were the result of sexual transmission.[311]

The spread of HIV in Mexico is exacerbated by stigma and discrimination, which act as a barrier to prevention, testing and treatment. Stigmatization occurs within families, in health services, with the police, and in the workplace.[308] A study conducted by Infante-Xibille in 2004 of 373 health care providers in three Mexican states described discrimination within health services. Testing was conducted only with perceived high-risk groups (often without informed consent), and AIDS patients were often isolated.[308]

A 2005 five-city participatory community assessment by Colectivo Sol (a non-governmental organization) found that some HIV hospital patients had a sign over their beds stating they were HIV-positive. In León, Guanajuato, researchers found that 7 out of 10 people in the study had lost their jobs because of their HIV status. The same study also documented evidence of discrimination that men who have sex with men experienced within their families.[308]

In August 2008, Mexico hosted the 17th International AIDS Conference, a meeting that contributed to overcoming stigmas and highlighting the achievements in the struggle against the illness.[312] In late 2009, Health Secretary José Ángel Córdova said in a statement that Mexico had met the United Nations Millennium Development Goal concerning HIV/AIDS (which demanded that countries begin to reduce the spread of HIV/AIDS before 2015). The HIV infection rate then was 0.4 percent, below the 0.6 percent target set by the World Health Organization for Mexico.[312]

About 70 percent of people requesting treatment for HIV/AIDS arrive without symptoms of the disease, which increases life expectancy by at least 25 years.[312] Treatment for HIV/AIDS in Mexico is free, and is offered at 57 specialized clinics to people living with HIV.[312] The Mexican Government spends about $2 billion MXN (US$151.9 million) each year fighting the disease.[312]

Summary table

| Same-sex sexual acts legal | |

| Equal age of consent (18) | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | |

| Same-sex marriage(s) | |

| Recognition of same-sex couples | |

| Adoption by single LGBT persons | |

| Stepchild adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Gays, lesbians and bisexuals allowed to serve in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Automatic parenthood on birth certificates for children of same-sex couples | |

| Conversion therapy banned on minors | |

| Access to IVF for lesbians | |

| Commercial surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSMs allowed to donate blood |

- 1 2 Only in Mexico City, Aguascalientes, Baja California, Baja California Sur, Campeche, Chiapas, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Colima, Durango, Hidalgo, Jalisco, Michoacán, Morelos, Nayarit, Nuevo León, Puebla, Querétaro, Quintana Roo, San Luis Potosí, and Veracruz

- ↑ Only in Mexico City, Baja California, Baja California Sur, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Colima, Durango, Hidalgo, Jalisco, the State of Mexico, Michoacán, Morelos, Nayarit, Oaxaca, Puebla, Quintana Roo, San Luis Potosí, Sinaloa, Sonora, Tlaxcala, and Zacatecas.

- ↑ Only in Mexico City, Baja California, Baja California Sur, Colima, Hidalgo, Jalisco, the State of Mexico, Nuevo Leon, Oaxaca, Puebla, Querétaro, Sinaloa, Sonora, Tlaxcala, Yucatán, and Zacatecas

See also

General:

References

- 1 2 3 Dynes, Johansson, p. 806.

- ↑ Reding, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 4 Evans, Len (1996). "Gay Chronicles from the Begining [sic] of Time to the End of World War II". Gay in Sacramento. Archived from the original on 6 May 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ↑ Reding, p. 17.

- ↑ Dynes, Johansson, p. 805.

- 1 2 "Congress beckons as transvestite taps support for gay rights (Mexico)". Free Republic. 5 July 2003. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2023.

- 1 2 "69% approve EPN's gay marriage changes". Mexico News Daily. 30 May 2016. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ↑ "Thousands march in Mexico against proposal to allow same-sex marriage". The Guardian. 10 September 2016. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 "LGBTQ History: Mexico" (PDF).

- ↑ "Con libro, revive marchas de orgullo gay en Monterrey". 26 June 2016.

- 1 2 "Decreto por el que se modifica la denominación del Capítulo I del Título Primero y reforma diversos artículos de la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos" (PDF). 10 June 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 November 2012. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 "Decreto por el que se modifica la denominación del Capítulo I del Título Primero y reforma diversos artículos de la Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos" (PDF) (in Spanish). Proceso Legislativo. 10 June 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ↑ "Muxes: gender-fluid lives in a small Mexican town". The Guardian. 27 October 2017.

- ↑ Reding, p. 18.

- ↑ Peter Herman Sigal. From moon goddesses to virgins: the colonization of Yucatecan Maya sexual desire. p. 213. University of Texas Press, 2000. ISBN 0-292-77753-1.

- ↑ Greenberg, David F. (29 October 2008). The Construction of Homosexuality. University of Chicago Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0226219813.

- ↑ Cecelia F. Klein and Jeffrey Quilter, Gender in Pre-Hispanic America. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, D.C