.jpg.webp)

Anthony de la Roché (spelled also Antoine de la Roché, Antonio de la Roché or Antonio de la Roca in some sources) was a 17th-century English merchant who in 1675, during a commercial voyage between Europe and South America, was blown off course and visited the Antarctic island of South Georgia, making the first discovery of land south of the Antarctic Convergence. He was born in London to a French Huguenot father and an English mother.[1][2][3]

1675 voyage

Discovery of Roché Island / South Georgia

Having acquired a 350-ton ship and a bilander of 50 tons in Hamburg, with 56 men in the two vessels, La Roché obtained permission by the Spanish authorities to trade in Spanish America. He called at the Canary Islands in May 1674, and in October that year arrived in the port of Callao in the Viceroyalty of Peru by way of Le Maire Strait and Cape Horn. On his return voyage, the vessels were careened on the coast of Chiloé Island (Chile) and sailed for Baía de Todos os Santos (Salvador, Brazil).

In April 1675 La Roché rounded Cape Horn and was overwhelmed by tempestuous conditions in the tricky waters off Staten Island (Isla de los Estados). He failed to make Le Maire Strait as desired, nor could he round the east extremity of Staten Island "to sail into the No. Sea by Brouwer’s Strait" (a mythical passage present on the old maps since the 1643 Dutch expedition of Admiral Hendrik Brouwer), and was carried far away to the east instead. Eventually, they found refuge in one of South Georgia's southern bays – possibly Drygalski Fjord or nearby Doubtful Bay, according to Matthews and other authors[4][1][5] – where the battered ships anchored for a fortnight.

According to La Roché's report published in French in London in 1678[6] and its surviving 1690 Spanish summary by Captain Francisco de Seixas y Lovera[7] (translated into English by Alexander Dalrymple, the first Hydrographer of the British Admiralty), "they found a Bay, in which they anchored close to a Point or Cape which stretches out to the Southeast with 28. 30. and 40. fathoms sand and rock".[6][8][9] The surrounding glaciated, mountainous terrain was described as "some Snow Mountains near the Coast, with much bad Weather". Once the weather cleared up, they set sail and while rounding the southeast extremity of South Georgia sighted Clerke Rocks, a group of conspicuous rocky islets extending 11 km and rising to 244 m some 60 km to the east-southeast.[1][5]

Variant routes

British naval officer and author James Burney conjectured that La Roché might have visited one of the Falkland Islands rather than South Georgia, and sailed between East Falkland and Beauchene Island on his departure.[10] In a variant version, Argentine historian Ernesto Fitte identified La Roché Strait with the Falkland Sound separating the two main islands of the Falklands archipelago.[11] That passage, however, is over 100 km long – no way of disemboguing through it “in 3 Glasses” – and narrowing to less than 5 km rather than “10 leagues little more or less.” Argentine naval officer and historian Laurio Destefani identified Roché Island with Beauchene Island itself.[12] Yet with its elevation of 70 m Beauchene is hardly the “high land” described in Seixas y Lovera’s summary. The Falklands are not known for their “snow mountains near the coast” either.

Another drawback of Burney's conjecture and its variants would be that La Roché approached his island from the west (“the Land which they now began to see toward the East”), and in such a westerly location (actually, in any location within visibility range of the Falklands) he would have been well into the “North Sea” even before his two-week anchorage and before sailing his strait – something refuted by the report narrating that, on departure, “steering ENE they found themselves in the No. Sea.” Indeed, the relevant section of Seixas y Lovera’s sailing directions for the Magellanic Region is titled “Of the discovery made by Antonio de la Roché of another New Passage from the North Sea to the South Sea.”[6]

For some time in the 20th century, yet another variant version of Strait de la Roché was the small passage at the northwest extremity of South Georgia shown on British Admiralty charts and in some dictionaries as “La Roché Strait,” “La Roché Strasse” or “Estrecho La Roche.” This version was dismissed on account of its discord with the historical evidence, and the passage renamed Bird Sound presently.[13][14]

Gough Island landing

Several days after his departure from South Georgia, La Roché came across another uninhabited island, "where they found water, wood and fish", and spent six days "without seeing any human being", thus making what some historians believe was the first landing on the South Atlantic island that had been discovered by the Portuguese navigator Gonçalo Álvares in 1505 or 1506 (and better known as Gough Island since 1731).[6][9][15]

La Roché successfully reached the Brazilian port of Salvador, and eventually arrived in La Rochelle, France on 29 September 1675.[6][8][4][16][2]

Legacy

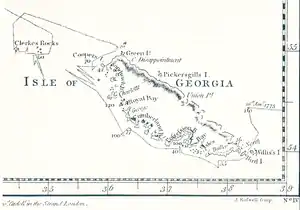

Soon after the 1675 voyage, cartographers started to depict on their maps Roché Island with Strait(s) de la Roché separating it from an Unknown Land on the southeast, honouring the mariner.[5][17] Both he and his geographic discoveries were included in encyclopedic editions and dictionaries.[18][19][20][21]

Captain James Cook was aware of La Roché's discovery, mentioning it in his logbook upon approaching South Georgia one hundred years later in January 1775.[22] Nevertheless, Cook made the first recorded landing, and surveyed and mapped Roché Island, renaming it for King George III in the process.[23] Naturalist Georg Forster, scientist in Cook’s expedition, also knew of La Roche’s discovery.[24]

Brazilian historian Varnhagen believed that South Georgia might have been discovered as early as April 1502 by the Portuguese expedition of Gonçalo Coelho, finding evidence of this in an episode reported by Florentine Amerigo Vespucci.[25] According to the latter’s account, from Brazil the expedition headed south and reached 52°S latitude, from where, after a four-day voyage in turbulent weather they encountered land and sailed a hundred kilometers along a rocky coast in severe cold weather.

Vespucci made no mention of snow/ice cover, something with which South Georgia invariably impresses seafarers. He wrote, however, that the night there was 15 hours long, which on the date in question was true 2600 km south of 52°S – a location unattainable in four days.[5] According to British historian Robert Headland, the analysis of historical evidence refutes Varnhagen’s hypothesis.[1]

La Roché's discoveries were commented on in the logbooks of explorers such as Britain's George Vancouver,[26] French La Pérouse[9] and Russia's von Bellingshausen,[27] and in The Nautical Magazine for 1835,[28] and featured in Laurie’s authoritative Sailing Directions by John Purdy.[29]

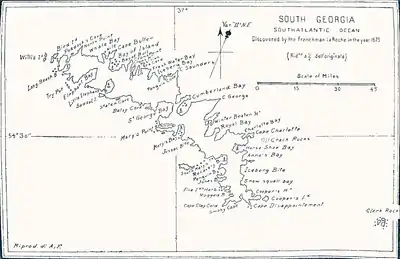

The second-ever map of South Georgia, made in 1802 by Captain Isaac Pendleton of the American sealing vessel Union and reproduced by the Italian polar cartographer Arnaldo Faustini in 1906, was entitled South Georgia; Discovered by the Frenchman La Roche in the year 1675.[30] While Pendleton probably erred regarding La Roché's nationality due to his French last name, British historian Peter Bradley noted that “(d)espite the suggestion that La Roché was English, the name and the return to La Rochelle … appear to indicate a French connection.”[31]

La Roché was quoted in relation with his compass variation data, too.[32][10]

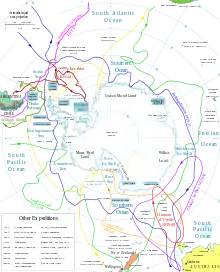

Maps showing La Roché's discovery

A good number of 17th and 18th century maps reflected the geographical knowledge gained from La Roché's 1674-75 voyage, among them the following:

- Albernaz, J.T., J. de Attayde e F. de Seixas y Lovera. Mapas generales originales y universales des todo el orue con los puertos principales y fortalezas de Ambas Indias y una descripcion topographica de la region Austral Magallonica año de 1692. A Portuguese map published in 1630, appended by the linked Spanish insert in 1692.

- Godson, William. (1702). A new and correct map of the world. London: George Willdey.

- L'Isle (or Lisle), Guillaume de & Charles-Louis Simonneau. (1703). Carte du Paraguai, du Chili, du Detroit de Magellan. Paris.

- L'Isle (or Lisle), Guillaume de; J. Covens & C. Mortier. (1705). L'Amerique Meridionale. Paris.

- L'Isle (or Lisle), Guillaume de. (1708). L'Amerique Meridionale Dressee sur les Observations de Mrs. de l'Academie Royale des Sciences. Amsterdam: Peter Schenk / Paris edition.

- Senex, John. (1710). South America corrected from the Observations communicated to the Royal Society's of London & Paris. London.

- Visscher, Nicolaes. (1710). Carte du Paraguay, du Chili, Detroit de Magellan & Terre de Feu dans l'Amerique Meridionale. Amsterdam.

- Moll, Herman. (1711). A New & Exact Map of the Coast, Countries and Islands within ye Limits of ye South Sea Company. London / 1726 edition.

- Moll, Herman. (1712-15). This map of South America, according to the newest and most exact observations. London.

- Price, Charles. (ca. 1713). South America corrected from the observations communicated to the Royal Society's of London and Paris. London.

- Van der Aa, Pieter. (1714). L'Amérique méridionale. Leiden.

- Chatelain, Henry A. (1714). Nouvelle Carte de Géographie de la Partie Méridionale de l'Amérique. Amsterdam.

- L'Isle (or Lisle), Guillaume de. (1717). Carte du Paraguai, du Chili, du Detroit de Magellan. Amsterdam.

- De Fer, Nicolas. (1720). Partie la plus méridionale de l'Amérique, où se trouve le Chili, le Paraguay, et les Terres Magellaniques avec les Fameux Détroits de Magellan et de Le Maire. Paris.

- Covens, J. & C. Mortier. (1730). Carte du Paraguay, du Chili, du Detroit de Magellan &c. Amsterdam.

- Moll, Herman. (1732). A map of Chili, Patagonia, La Plata and ye south part of Brasil. London.

- Techo, Nicolas. (1733). Typus Geographicus Chili a Paraguay Freti Magellanici &c. Nuremberg.

- L'Isle (or Lisle), Guillaume de & Giambattista Albrizzi. (1740). Carta Geografica della America Meridionale. Venice.

- Seale, Richard W. (ca. 1744). A Map of South America. With all the European Settlements & whatever else is remarkable from the latest & best observations. London.

- Cowley, John. (ca. 1745). A Map of South America. London.

- Homann Heirs, Johann Haas. (1746). Americae Mappa generalis. Nuremberg.

- Buache, Philippe. (1754). Carte des Terres Australes, Comprises entre le Tropique du Capricorne et le Pôle Antarctique. Paris.

- Jefferys, Thomas. (ca. 1754). South America. London.

- Le Rouge, Georges-Louis. (1756). Amerique Meridionale. Paris.

- Seutter, Matthäus. (1757). Le Pays de Perou et Chili. Augsbourg.

- Lotter, Tobias Conrad. (1757). America Meridionalis. Augsburg.

- Delarochette, Louis. (ca. 1763). South America From the latest Discoveries. London: John Bowles.

- Jefferys, Thomas. (1768). A chart of the ocean between South America and Africa with the tracks of Dr. Edmund Halley in 1700 and Monsr. Lozier Bouvet in 1738. London: J. Nourse.

- Phinn, Thomas. (1771). South America. Edinburgh.

- Guthrie, William. (1771). South America. London.

- Bowen, Thomas. (1772). South America from the best Authorities. London: G. Robinson.

- Sayer, Robert. (1772). A General Map of America divided into North and South, and West Indies: with the Newest Discoveries. London.

- Jefferys, Thomas. (1776). South America. London.

- Jefferys, Thomas. (1776). A Chart of North and South America. London.

- Gibson, John. (1777). A New Map of the Whole Continent of America, divided into North and South America and West Indies, with a Descriptive Account of the European Possessions, as Settled by the Definitive Treaty of Peace, Concluded at Paris, Feby. 10th, 1763, Compiled from Mr. D'Anville's Maps of that Continent, and Corrected in the Several Parts belonging to Great Britain, from the Original Materials of Governor Pownall, MP. London: Robert Sayer.

- Robert de Vaugondy, Didier. (1777). Hemisphère Australe ou Antarctique. Paris.

- Elwe, Ian Barend. (1792). L'Amérique Méridionale. Amsterdam.

- Arrowsmith, Aaron. (1794). Map of the World on a Globular Projection, Exhibiting Particularly the Nautical Researches of Capn. James Cook, F.R.S. with all the Recent Discoveries to the Present Time. London.

- D'Anville, Jean Baptiste Bourguignon. (1795). A Map of South America. London: Laurie & Whittle.

Fragment of Seale's 1744 map featuring Roche Island, Straits de la Roche and Unknown Land |

1802 Map of South Georgia by Capt. Isaac Pendleton |

Honours

Roché Peak, the summit of Bird Island, South Georgia, and Roché Glacier in Vinson Massif, Antarctica are named for Anthony de la Roché.[33][34]

The Overseas Territory of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands issued in 2000 a two pound coin commemorating the 325th anniversary of the discovery of South Georgia by La Roché.[35]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Headland, Robert K. (1984). The Island of South Georgia. Cambridge University Press. 293 pp. ISBN 0-521-25274-1 (1982 concise version)

- 1 2 Capt. Ferrer Fougá, Hernán. (2003). El hito austral del confín de América. El cabo de Hornos. (Siglos XVI–XVII–XVIII). (Primera parte) Archived 10 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Revista de Marina, Valparaíso, N° 6.

- ↑ ICJ. (1955). Origins of the British Titles, Historic Discoveries and Acts of Annexation by British Nationals in the Period 1675-1843. Application instituting proceedings: Antarctica cases (United Kingdom v. Argentina; United Kingdom v. Chile). International Court of Justice, 4 May 1955.

- 1 2 Matthews, L. Harrison. (1931). South Georgia: The British Empire's Sub-Antarctic Outpost. Bristol: John Wright; and London: Simpkin Marshall.

- 1 2 3 4 Ivanov, L. and N. Ivanova. Roché Island / South Georgia. In: The World of Antarctica. Generis Publishing, 2022. pp. 68–70. ISBN 979-8-88676-403-1

- 1 2 3 4 5 Capt. Seixas y Lovera, Francisco de. Descripcion geographica, y derrotero de la region austral Magallanica. Que se dirige al Rey nuestro señor, gran monarca de España, y sus dominios en Europa, Emperador del Nuevo Mundo Americano, y Rey de los reynos de la Filipinas y Malucas. Madrid: Antonio de Zafra, 1690. (Sailing Directions for the Magellanic Region, narrate the discovery of South Georgia by the Englishman Anthony de la Roché in April 1675 (Capítulo IIII Título XIX p. 27 or p. 99 of pdf); Relevant fragment.)

- ↑ Lage-Seara, Antonio. (2022.) Francisco de Seyxas: corsario, científico y aventurero. Mundiario, August 2023.

- 1 2 Dalrymple, Alexander. (1775). A Collection of Voyages Chiefly in The Southern Atlantick Ocean. London. pp. 85–88.

- 1 2 3 J.-F.G. de la Pérouse. (1807). A Voyage Round the World, Performed in the Years 1785, 1786, 1787, and 1788, by the Boussole and Astrolabe: Under the Command of J.-F.G. de la Pérouse. Ed. F.A.M. de la Rúa. Volume 1. London: Lackington, Allen, and Company. pp. 71–81.

- 1 2 Burney, J. (1813). A Chronological History of the Voyages and Discoveries in the South Sea or Pacific Ocean: Part III: From the Year 1620, to the Year 1688. London: Luke Hansard and Sons. pp. 395–403. (Discusses various aspects of La Roché's voyage.)

- ↑ Fitte, Ernesto J. (1968). La disputa con Gran Bretaña por las islas del Atlántico Sur. Buenos Aires: Emecé. p. 47.

- ↑ Destefani, Laurio H. (1982). The Malvinas, the South Georgias and the South Sandwich Islands: the conflict with Britain. Buenos Aires: Edipress S.A. p. 111.

- ↑ GSGSSI. (2024). South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands Gazetteer. London: UK Antarctic Place-names Committee.

- ↑ Pierrou, Enrique Jorge. (1970). Toponimia del Sector Antártico Argentino. Buenos Aires: Armada Nacional. 746 p.

- ↑ Wace, Nigel Morritt. (1969). The discovery, exploitation and settlement of the Tristan da Cunha Islands. Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of Australasia (South Australian Branch) 10: 11–40.

- ↑ Headland, Robert K. (1990). Chronological List of Antarctic Expeditions and Related Historical Events. Cambridge University Press. p. 65. ISBN 0-521-30903-4

- ↑ McCarl, Clayton. (2020). Tosco e imperfecto, con mucho de fabulado: El mapa de Francisco de Seyxas y Lovera de la Región Austral Magallánica. Magallania. Vol.48. No. especial Punta Arenas. (Analyzes the 1692 modification by de Seixas y Lovera of Albernaz and de Attayde's 1630 map.)

- ↑ Coleti, Giandomenico. (1771). Dizionario Storico-Geografico dell’ America Meridionale. Venezia: Stampedaria Coleti. p. 117.

- ↑ Alcedo, Antonio de. (1788). Diccionario Geográfico-Histórico de las Indias Occidentales ó América. Tomo IV. Madrid: Manuel Gonzalez. p. 435.

- ↑ USBGN. (1956). Geographic Names of Antarctica. Washington, D.C.: Office of Geography, Department of the Interior. pp. 9, 11, 287.

- ↑ David, Andrew. (2012–21). Roché, Antonio de la. In: The Dictionary of Falklands Biography (including South Georgia). Ed. David Tatham.

- ↑ Cook, James. (1777). A Voyage Towards the South Pole, and Round the World. Performed in His Majesty's Ships the Resolution and Adventure, In the Years 1772, 1773, 1774, and 1775. In which is included, Captain Furneaux's Narrative of his Proceedings in the Adventure during the Separation of the Ships. Volume II. London: Printed for W. Strahan and T. Cadell. (Relevant fragment)

- ↑ Cook, James. (1777). Chart of the Discoveries made in the South Atlantic Ocean, in His Majestys Ship Resolution, under the Command of Captain Cook, in January 1775. W. Strahan and T. Cadel, London. (Relevant fragment)

- ↑ Forster, George. A Voyage Round the World in His Britannic Majesty's Sloop Resolution Commanded by Capt. James Cook, during the Years 1772, 3, 4 and 5 (2 vols.). vol. 2. London, 1777. p. 524.

- ↑ Varnhagen, Francisco Adolfo de. (1865.) Amerígo Vespucci: Son caractère, ses écrits mème les moins authentiques), sa vie et ses navigations, avec une carte indiquant les routes. Lima: Mercurio. 121 p.

- ↑ Vancouver, George. (1798). A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean, and Round the World. Vol. III. London: G.G. and J. Robinson, and J. Edwards. 505 pp.

- ↑ Беллингсгаузен, Фадей Ф. Двукратные изыскания в Южном Ледовитом Океане, и плавание вокруг света, в продолжение 1819, 1820 и 1821 годов. Две части. С атласом в 64 л. Санкт-Петербург. В типографии Глазунова, 1831. Ч. I 397 с., ч. II 326 с. / English version

- ↑ Becher, A.B., ed. (1835). Isle Grande, South Atlantic Ocean. The Nautical Magazine. London. p. 1–8. (Discusses La Roché's voyage.)

- ↑ J. Purdy. Laurie’s Sailing Directory of the Ethiopic or Southern Atlantic Ocean; Including the Coasts of Brasil etc. to the Rio de la Plata, the Coast thence to Cape Horn, and the African Coast to the Cape of Good Hope etc; Including the Islands between the Two Coasts. 4th edition. London: Richard Laurie, 1855. 578 pp.

- ↑ Faustini, Arnaldo. (1906). Di una carta nautica inedita della Georgia Austral. Revista Geografica Italiana, Firenze, 13(6). pp. 343–351.

- ↑ Bradley, Peter T. (1999). British maritime enterprise in the New World: From the late fifteenth to the mid-eighteenth century. Lewiston, NY: E. Mellen Press. p. 443.

- ↑ Seixas y Lovera, Francisco de. Théâtre Naval Hydrographique, des Flux et Reflux, des Courans Des Mers, Détroits, Archipels & Passages aquatiques du Monde, & des Variations du Compas Marin, & effets de la Lune; avec les Vents generaux & particuliers qui regnent aux quatre Regions Maritimes de l’Univers. Paris: Chez Pierre Gissey; Versailles: Chez Pierre le Monnier, 1704. p. 191.

- ↑ Alberts, Fred G., ed. (1995.) Roché Peak. Geographic Names of the Antarctic. Second edition. National Science Foundation. 834 pp.

- ↑ Roché Glacier. SCAR Composite Antarctic Gazetteer.

- ↑ Antoine de la Roché: Discovery 1675: Two Pounds. South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands, 2000.