| Adzebills | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton of A. otidiformis, Canterbury Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Gruiformes |

| Family: | †Aptornithidae Mantell, 1848 |

| Genus: | †Aptornis Owen, 1844 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

_601651_(cropped).jpg.webp)

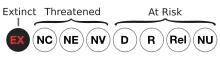

The adzebills, genus Aptornis, were two closely related bird species, the North Island adzebill, (Aptornis otidiformis), and the South Island adzebill, (Aptornis defossor), of the extinct family Aptornithidae. The family was endemic to New Zealand. A tentative fossil species, (Aptornis proasciarostratus), is known from the Miocene Saint Bathans fauna.[3]

Taxonomy

Adzebills were first scientifically described in 1844 by biologist Richard Owen, who mistook them for a small species of moa.[4] The first species named was Dinornis otidiformis (later Aptornis), with the specific epithet referring to its similarity in size to the great bustard (Otis tarda).[5]

They have been placed in the Gruiformes but this is not entirely certain. It was also proposed to ally them with the Galloanserae.[6] Studies of morphology and DNA sequences place them variously close to and far off from the kagu of New Caledonia,[7] as well as the trumpeters.[8] However, on first discovery of fossils, they were mistaken for ratites, specifically small moa. Its morphological closeness to the kagu may be the result of convergent evolution, although New Zealand's proximity to New Caledonia and shared biological affinities (the two islands are part of the same microcontinent) has led some researchers to suggest they share a common ancestor from Gondwana. The Gondwanan sunbittern is the closest living relative of the kagu, but these are not close to the Gruiformes proper (i.e. cranes, rails and allies).[9][10]

_601687.jpg.webp)

A 2011 genetic study found A. defossor to be a gruiform. There are no available DNA sequences for A. otidiformis, but it was assumed the two species were more closely related to each other than to other birds.[11]

In 2019 two studies came forth with more in-depth phylogenetic methods. The first from Boast et al. (2019) using data from near-complete mitochondrial genome sequences found adzebills to be closely related to the family Sarothruridae, the flufftails.[12] Shortly after another study by Musser and Cracraft (2019), using both morphological and molecular data, found support for adzebills to be closely related to trumpeters of the family Psophiidae instead.[8] The authors took account of Boast et al. (2019) dataset and found it took 18 more steps to support the Aptornithidae-Sarothruridae clade than for Aptornithidae-Psophiidae.

Description

The adzebills were about 80 centimetres (31 in) in length with a weight of 18 kilograms (40 lb), making them about the size of small moa (with which they were initially confused on their discovery) with enormous downward-curving and pointed bill, and strong legs.[13] They were flightless and had extremely reduced wings, smaller than those of the dodo compared to the birds' overall size, and with a uniquely reduced carpometacarpus.[14]

The two species varied mostly in size with the North Island adzebill being the smaller species; their coloration in life is not known however.

Habitat and behaviour

Their fossils have been found in the drier areas of New Zealand, and only in the lowlands. Richard Owen, who described the two species, speculated that it was an omnivore, and analysis of its bones by stable isotope analysis supports this. Levels of enrichment in 13C and 15N for two specimens of Aptornis otidiformis compared with values for a moa, Finsch's duck and insectivores like the owlet-nightjars suggested that the adzebill ate species higher in the food chain than insectivores.[15] They are thought to have fed on large invertebrates, lizards, tuataras and even small birds.

Extinction

The adzebills were never as widespread as the moa but were subjected to the same hunting pressure as these and other large birds by the settling Māori (and predation of eggs/hatchlings by accompanying Polynesian rats and dogs). They became extinct before the arrival of European explorers. The Māori name for A. defossor was "ngutu hahau".[1]

References

- Fain Matthew G., Houde Peter (2004). "Parallel radiations in the primary clades of birds". Evolution. 58 (11): 2558–2573. doi:10.1554/04-235. PMID 15612298. S2CID 1296408.

- Livezey Bradley C (1994). "The carpometacarpus of Apterornis" (PDF). Notornis. 41 (1): 51–60. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-26.

- Weber Erich, Hesse Angelika (1995). "The systematic position of Aptornis, a flightless bird from New Zealand". Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg. 181: 292–301.

- Worthy Trevor H (1989). "The glossohyal and thyroid bone of Aptornis otidiformes" (PDF). Notornis. 36 (3): 248. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-30.

- Worthy, Trevor H., & Holdaway, Richard N. (2002) The Lost World of the Moa, Indiana University Press:Bloomington, ISBN 0-253-34034-9

- North Island Adzebill. Aptornis otidiformis. by Paul Martinson. Artwork produced for the book Extinct Birds of New Zealand, by Alan Tennyson, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2006

- South Island Adzebill. Aptornis defossor. by Paul Martinson. Artwork produced for the book Extinct Birds of New Zealand, by Alan Tennyson, Te Papa Press, Wellington, 2006

Footnotes

- 1 2 "Aptornis defossor. NZTCS". nztcs.org.nz. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ↑ "Aptornis otidiformis . NZTCS". nztcs.org.nz. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ↑ Worthy, Trevor H.; Tennyson, Alan J. D.; Scofield, R. Paul (2011). "Fossils reveal an early Miocene presence of the aberrant gruiform Aves: Aptornithidae in New Zealand". Journal of Ornithology. 152 (3): 669–680. doi:10.1007/s10336-011-0649-6. S2CID 37555861.

- ↑ Dickinson, Mike (2019). "The Mystery of the Adzebill". New Zealand Geographic. No. 157. Auckland: Kowhai Media. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ↑ Owen, Richard (1849). "On Dinornis (Part X) an extinct genus of tridactyle Struthious Birds, with descriptions of portions of Skeleton of five Species which formerly existed in New Zealand". Transactions of the Zoological Society of London. Published for the Zoological Society of London by Academic Press. 3: 247. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ↑ Weber Erich, Hesse Angelika (1995). "The systematic position of Aptornis, a flightless bird from New Zealand". Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg. 181: 292–301.

- ↑ Cracraft, J.L. (1982) Phylogenetic relationships and transantarctic biogeography of some gruiform birds. Geobios 6: 393–402.

- 1 2 Grace M. Musser; Joel Cracraft (2019). "A new morphological dataset reveals a novel relationship for the adzebills of New Zealand (Aptornis) and provides a foundation for total evidence neoavian phylogenetics" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3927): 1–70. doi:10.1206/3927.1. hdl:2246/6937. S2CID 155704891.

- ↑ Prum, R.O.; et al. (2015). "A comprehensive phylogeny of birds (Aves) using targeted next-generation DNA sequencing". Nature. 526 (7574): 569–573. Bibcode:2015Natur.526..569P. doi:10.1038/nature15697. PMID 26444237. S2CID 205246158.

- ↑ H Kuhl, C Frankl-Vilches, A Bakker, G Mayr, G Nikolaus, S T Boerno, S Klages, B Timmermann, M Gahr (2020) An unbiased molecular approach using 3’UTRs resolves the avian family-level tree of life. Molecular Biology and Evolution. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa191

- ↑ Lanfear, R.; Bromham, L. (2011). "Estimating phylogenies for species assemblages: A complete phylogeny for the past and present native birds of New Zealand". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 61 (3): 958–963. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2011.07.018. PMID 21835254.

- ↑ Alexander P. Boast; Brendan Chapman; Michael B. Herrera; Trevor H. Worthy; R. Paul Scofield; Alan J. D. Tennyson; Peter Houde; Michael Bunce; Alan Cooper; Kieren J. Mitchell (2019). "Mitochondrial genomes from New Zealand's extinct adzebills (Aves: Aptornithidae: Aptornis) support a sister-taxon relationship with the Afro-Madagascan Sarothruridae". Diversity. 11 (2): Article 24. doi:10.3390/d11020024. hdl:2440/119533.

- ↑ "South Island adzebill | New Zealand Birds Online".

- ↑ Livezey Bradley C (1994). "The carpometacarpus of Apterornis" (PDF). Notornis. 41 (1): 51–60. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-26.

- ↑ Worthy, T. H., Richard N. Holdaway (2002):p. 212