.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The architecture of the Kansas City Metropolitan Area, especially Kansas City, Missouri, includes major works by some of the world's most distinguished architects and firms, including McKim, Mead and White; Jarvis Hunt; Wight and Wight; Graham, Anderson, Probst and White; Hoit, Price & Barnes; Frank Lloyd Wright; the Office of Mies van der Rohe; Barry Byrne; Edward Larrabee Barnes; Harry Weese; and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill.

Kansas City, Missouri was founded in the 1850s at the confluence of the Missouri and Kaw rivers and grew with the expansion of the railroads, stockyards, and meatpacking industry. Prominent citizens settled in the Quality Hill neighborhood and commissioned fine homes primarily in Italianate Renaissance Revival style, which continued to be the major influence for new structures past the turn-of-the-century. George Kessler's urban plan for Kansas City with its expansive park and boulevard system, inspired by the City Beautiful Movement, made a profound and lasting impact on the city.

The core of the downtown area was developed in an early 20th-century building boom that continued into the Great Depression. Emporis ranks Kansas City among the top ten US cities for art deco architecture.[1] Municipal Auditorium, the Kansas City Power and Light Building, and Jackson County Courthouse have been called "three of the nation's Art Deco treasures".[2]: 23 J.C. Nichols, a prominent developer of commercial and residential real estate, developed the Country Club Plaza (by Edward Buehler Delk and Edward Tanner), and was active in the promotion of lasting architectural landmarks such as Liberty Memorial (Harold Van Buren Magonigle), and Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Wight and Wight).

The second period of building growth occurred from the 1960s through the 1980s. During this time, Kansas City, Missouri gained much of its modern glass skyscrapers, including One Kansas City Place, which is the tallest building in Missouri at 623 feet. Suburban growth spread into Johnson County, Kansas, with new homes and mid-rise office buildings concentrated in Overland Park and Leawood, Kansas.

After a period of urban decline and stagnation in the inner city, downtown Kansas City has been revived by several major new works of architectural design. T-Mobile Center arena (2007), the Power & Light District entertainment development (2007), the Bloch Building featuring contemporary artwork added to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (2007), H&R Block World Headquarters located in the Power & Light District (2006), the 2555 Grand office building near Crown Center (2003), Charles Evans Whittaker Federal Courthouse in the Government District (2000), Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art (1994), American Century Towers by the Country Club Plaza (1991 and 1994), Bartle Hall Convention Center expansion adding the iconic 4 towers with artwork atop each (1994), and the biotechnology and medical institution situated near UMKC Stowers Institute for Medical Research (1994) are among the most prominent and recognizable.

Early architecture

Kansas City, Missouri's first highrise is the New York Life Insurance Building, completed in 1890. It has twelve floors at a height of 180 feet (55 m) and is the first local building with elevators. After the New York Life Building was completed, Kansas City followed the national trend of constructing a plethora of buildings above ten stories. Within fifty years of the building's construction, more than fifty buildings with more than ten floors each were built in and around downtown.

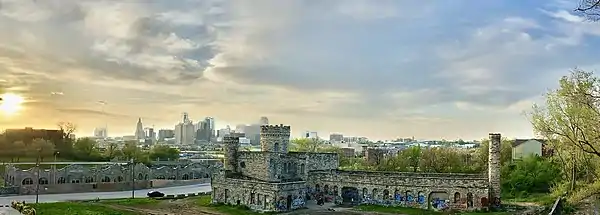

In the late 1800s, architectural leadership of the booming Kansas City included architect James Oliver Hogg[3] and Superintendent of Buildings A. Wallace Love.[4][3] The upper class, especially those living at the segment of Troost Avenue nicknamed Millionaire's Row,[5] considered the European castellated style to be in vogue.[3] In 1897, the city government inaugurated one of the earliest architectural centerpieces of the area, in the form of the new city workhouse castle with dedicated jail. It was built from two-foot-thick yellow limestone, quarried onsite by inmate labor, at a total cost of US$25,700 (equivalent to about $904,000 in 2022). It was designed by Hogg and Love,[3][4] with input from workhouse Superintendent Major Brant, who hailed it as "the best building Kansas City has".[6] Its 20-foot castellated towers, parapet walls, and Scotch coping were inspired by 16th century Europe's Romanesque Revival architecture[3] to give "the impression of an ancient taronial castle".[7] In 1909, Dr. Flavel B. Tiffany (founder of Tiffany Springs) moved away from Millionaire's Row[5] and into his new 4,200 square feet (390 m2) home in Pendleton Heights, built for $75,000 (equivalent to about $2,443,000 in 2022),[8] with walls of solid stone from a quarry at 2nd and Lydia, based on his love of the Tudor architecture of castles seen in his travels to England and Scotland.[5]

Louis Curtiss, among Kansas City's most innovative architects, designed the Boley Clothing Company Building, which is renowned as "one of the first glass curtain wall structures in the world".[2]: 29 The six-story building also features cantilever floor slabs, cast iron structural detailing, and terra cotta decorative elements.

Art Deco, Terra Cotta, and Gothic styles

Kansas City underwent an early skyscraper boom between 1920 and 1940, including the Power and Light Building, Oak Tower, City Hall, the Jackson County Court House, the Bryant Building, and the Fidelity National Bank building. Today, many of these buildings are being renovated for various uses, from residential lofts to office spaces. Oak Tower was once a building filled with terra cotta and gothic architecture. In an effort to modernize the then-40-year-old building in the 1970s, however, Southwestern Bell tore down its gargoyles and placed cladding over.

Frank Lloyd Wright buildings

Frank Lloyd Wright designed three buildings that stand in the Kansas City area: the Frank Bott Residence (1950), the Clarence Sondern House (1940), and Community Christian Church (1940).[9]

Community Christian Church

This Frank Lloyd Wright building is on Main at East 46th Street, across from the Country Club Plaza's main shopping district. In April 1940, Community Christian Church came to Wright and asked him to design a new building for them after a fire had destroyed its previous church building. Wright based his design on a parallelogram including some features previously conceived for his last building for Johnson Wax Company, along with one additional unique feature: a spire of light. Due to high building costs, the scale of the church was reduced during construction. The auditorium was cut back from a planned 1,200 seats to 900 seats, many details were eliminated, and the building was sheathed in gunite, a form of lightweight concrete, over Wright's objections. The spire of light also could not be built and illuminated due to technical limitations of the times. However, the church was dedicated on January 4, 1942, and served the congregation well.

In 1994, the Spire of Light was finally completed as planned. The components are housed on the church roof inside of a perforated dome on the building's northwestern corner. The spire is created by four (4) 16" xenon bulbs ignited by 40,000 volts of electricity, then, in combination with a parabolic reflector, produces 300 million candela of illumination (per light, 1.2 billion cp total) in a near perfect column.[10] The spire is visible for miles around Kansas City, and reportedly can be seen from 10 miles (16 km) north of the Plaza, depending on conditions. It has been calculated to stop at least 3 miles (4.8 km) up above the earth, about half the maximum height at which jet airplanes fly. The spire of light is lit regularly on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays, except religious holidays, and is one of the features of the annual Plaza lighting ceremony.

Tours of Community Christian Church are open to the public and free of charge.[11]

Modern and post-modern architecture

Kansas City had a building boom in the 1970s based on TWA's plans to use the city as the world hub for its new fleet of Boeing 747s and anticipated supersonic transports.

During this period Kansas City International Airport was built to TWA's specifications so that gates were within 100 feet (30 m) of the street. Hallmark Cards began construction of Crown Center. The city also built the Bartle Hall convention center. Architect Helmut Jahn's first major work was the revolutionary design for Kemper Arena, which had no columns blocking sight lines and was built in 18 months in time to attract the 1976 Republican National Convention.

The optimism of this era came to a crashing end when the Kemper Arena roof collapsed during a storm in 1979 (although no one was injured) and when skybridges at the new Hyatt Regency in Crown Center collapsed in the Hyatt Regency walkway collapse on July 17, 1981, in the worst engineering disaster in recorded history in terms of human lives. Both buildings were repaired and remain in use.

In addition to these disasters, TWA asked the city to extensively rebuild the terminals at the newly opened Kansas City International Airport so that it could have central checkpoints. The airport renovations had already come in at $100 million over budget, so the city refused. As a result, TWA moved its hub to St. Louis. In 2006, the city finally announced plans for a $250 million overhaul of the terminals to accommodate the security issues.

In the 1980s, the nation moved from the "modern" style of architecture (as inspired by architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe), building large, boxy structures, to a "postmodern" style. The two most noticeable postmodern buildings in the Kansas City skyline are the Town Pavilion (built in 1986) and One Kansas City Place (1988). One Kansas City Place is a taller, glass version of City Hall. The building rises 623 feet from its main entrance to the top of its spire and is Missouri's tallest office building.

Original Kansas City architecture

Kansas City's most profound influence on national architecture is the Kansas City-style of stadium that originated with the Kivett & Myers 1967 design for the Truman Sports Complex for the Kansas City Chiefs and Kansas City Royals. In an era when new stadiums were huge multiuse arenas, Kivett & Myers proposed baseball and football have their own arenas with dimensions most favorable to their sports and then covered with a rolling roof. Virtually all major league ballparks and stadiums since then have followed that model and most have been designed by one of two Kansas City architect firms that trace their stadium business roots to Kivett -- Populous and HNTB. The firms' headquarters are a few blocks apart in downtown Kansas City.

The most distinctive feature of any modern Kansas City building is its use of fountains. Kansas City calls itself the City of Fountains and has more than 200 fountains (with the claim that only Rome, Italy has more fountains). Probably the most famous is the J.C. Nichols Fountain on the Country Club Plaza. It's also the most photographed. Sculpted by France's Henri Greber in 1910, the fountain's mounted figures were originally planned for a Long Island estate. Each of the equestrian figures represents one of four great rivers of the world: Mississippi, Volga, Rhine and Seine.

Historical building restoration

Landmark Tower/One Park Place

This building used to be known as the BMA (Business Men's Assurance Company) Building. It is located south of downtown at the intersection of Southwest Tfwy and 31st Street, directly across from the Fox 4 News building and towers, and on the same block as Penn Valley skatepark.

Built in 1964, Landmark Tower was designed by architects at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, who also designed the Plaza Center Building at 800 West 47th Street. Its structural grid, which is clad in white Georgia marble, is projected out in front of the actual building. Landmark Tower earned the First Honor Award in 1964 from the American Institute of Architects and was featured in a 1965 exhibit by New York's Museum of Modern Art.

Renovation began in 2003. The only opposition occurred when developers wanted to build additional residential facilities inside the park adjacent to the tower. The One Park Place developers say the tower will hold between 150 and 200 residential units. Gastinger Walker Harden Architects is working with the developers on the renovations, respecting the original design, which was inspired by the "International" style.

The View

Located at 600 Admiral Boulevard, it was completed in 1967. The architects of this building were John L. Daw & Associates. The Vista del Rio was the first multi-story exposed concrete structural frame building allowed by federal specifications. It was also the first federally approved high-rise to use sheetrock for internal walls. It was originally built to inspire urban renewal in the previously dilapidated area; however, after a period of misuse, the building itself fell into deep disrepair. After much of its glass had been removed, it began to be used by more "troublesome" citizens. By the 1990s, maintenance and care became so bad that graffiti appeared throughout the structure and, unfortunately, even human remains were found around the premises.

Many predicted the destruction of this neglected building, but at the beginning of current downtown redevelopment, its future became much brighter. The Vista Del Rio became the View, turning from a public nuisance to a magnet for people wishing anew to live downtown.

Fidelity Bank and Trust/909 Walnut

This building is located at 909 Walnut Street (formerly 911 Walnut Street), in the north portion of downtown's Central Business District. Constructed in 1931 (at the same time as the Power and Light Building), it is 35 stories tall.

Built to replace the Fidelity National Bank and Trust Building that had existed on that site, it was designed by Hoit, Price and Barnes Architects, the same firm that designed the Power and Light Building. It won a local American Institute of Architects award in the 1930s during its construction. The twin towers at its top resemble those of notable buildings around the United States, such as 900 North Michigan in Chicago (built in 1989), or the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City (built in 1931). The building once had a large clock in its north tower that has long since been removed.[12]

In 2003, several proposals competed to turn this building into a residential tower. The building now houses 150-180 residential units, complete with rooftop terraces for its two multimillion-dollar penthouses.

New development

During the 1950s and 1960s, as many downtown residents moved south and north to Kansas City's sprawling suburbs; downtown's population dwindled. By the 1980s, downtown Kansas City consisted mostly of office towers, with few thriving neighborhoods remaining. However, major downtown redevelopment has brought back thousands of residents; with them has come a need for more buildings and more density.

In late 2004, H&R Block announced the construction of its new headquarters, a 17-story tower downtown that was completed in early 2007. The tower serves as the anchor of a six-block entertainment district neighboring the Central Business District. This project includes five new skyscrapers intended to bring additional entertainment, jobs, and housing to downtown.

Local architectural firms have major contracts with these and other new proposals. The two biggest are the Power and Light District, designed by Cordish Company of Baltimore, Maryland, and the 18,500-seat T-Mobile Center arena, originally named Sprint Center.

On October 6, 2006, ground was broken on the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts a 316,000-square-foot (29,400 m2) performing arts center. It serves the Kansas City Metropolitan Area as host to three resident companies: the Kansas City Symphony, Ballet, and Opera. The Kauffman Center held its grand opening in September 2011.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City completed the building of a new headquarters located southwest of Crown Center.

| Name | Floors | Year Completed | Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2555 Grand | 26 | 2003 | Office |

| H&R Block Tower | 17 | 2006 | Office |

| Kirkwood Circle | 13 | 2005 | Residential |

| 4646 Broadway | 13 | 2007 | Residential |

| Federal Reserve HQ | 14 | 2007 | Office |

| Plaza Colonnade | 10 | 2004 | Office |

| Plaza Vista | 10 | 2013 | Office |

| One Light | 25 | 2015 | Residential |

| Two Light | 23 | 2017 | Residential |

| Loews Kansas City Hotel | 30 | 2020 | Hotel |

See also

Buildings on National Register of Historic Places

References

- ↑ "Kansas City". Emporis. Archived from the original on February 14, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2021.

- 1 2 American Institute of Architects/Kansas City (2000). American Institute of Architects Guide to Kansas City Architecture & Public Art. Kansas City, Missouri: Highwater Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Honig, Esther (July 24, 2014). "What Is That? Kansas City's Vine Street Castle". NPR. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- 1 2 "Plans for a Workhouse". Kansas City Star. March 8, 1895. p. 6. Archived from the original on August 16, 2013. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- 1 2 3 "Pendleton Heights Holiday Homes Tour and Artist's Market". The Telegraph. December 5, 2019. Retrieved April 17, 2020.

- ↑ "Ready for Its Hobo Guests". The Kansas City Star. December 20, 1897. p. 3. Retrieved July 19, 2020.

- ↑ "The New Workhouse". The Kansas City Star. July 14, 1897. p. 2. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ↑ Bushnell, Michael (October 3, 2018). "The Northeast's "Tiffany Castle"". Northeast News. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ↑ "Frank Lloyd Wright Building Guide: Missouri Architecture". Archived from the original on 2009-10-28.

- ↑ Community Christian Church.org: Facts & Figures - Steeple. Archived 2008-05-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Community Christian Church: Tour Information. Archived 2008-05-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Traceries (March 20, 1997). "The Fidelity National Bank and Trust Company Building" National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (Report). Missouri Department of Natural Resources.

External links

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps - Kansas City

- www.skyscraperpage.com

- KC Skyscrapers