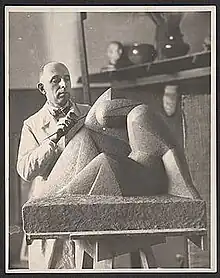

Arnold Rönnebeck (May 8, 1885 – November 14, 1947)[1] was a German-born American modernist artist and museum administrator. He was a vital member of both the European and American avant-garde movements of the early twentieth century before settling in Denver, Colorado. Rönnebeck was a sculptor and painter, but is best known for his lithographs that featured a range of subjects including New York cityscapes, New Mexico and Colorado landscapes and Native American dances.

Personal life and education

Arnold Rönnebeck was born in Nassau, Germany in 1885[2] to a well-educated family. His father, Richard, was an architect and encouraged Rönnebeck to follow in his footsteps. After two years of study at the Royal Art School in both Berlin and Munich, Rönnebeck decided to pursue sculpture and moved to Paris in 1908. He could speak German, French and English and read Greek and Latin. In Paris, he studied with Aristide Maillol (dates unknown, likely 1908-1909) and Emile Antoine Bourdelle from 1910-1913 at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière.[2] In 1912, Rönnebeck met the American Modernist painter, Marsden Hartley at Restaurant Thomas in Paris, and they became close friends as they moved through the avant-garde circles of Paris and Berlin. He regularly attended Gertrude Stein’s “salons” and according to Stein, “Rönnebeck was charming and always invited to dinner,”[3] together with Pablo Picasso, Mabel Dodge, and Charles Demuth. While living in Paris, Rönnebeck completed sculptural commissions for the wealthy and portraits of his friends. These would include a series of watercolors and ink drawings executed in 1912 of dancer, Isadora Duncan. These were likely done from memory after Rönnebeck saw her December 1911 performance at the Théàtre du Chatelet, in Paris. Rönnebeck exhibited three sculptures, including his 1912 bronze Head of Marsden Hartley, at the 1912 Salon d'Automne in Paris. In the 1913 Salon d'Autumne, he exhibited two pieces, including his now lost plaster Head of Charles Demuth.[4] His bust of Marsden Hartley was included in Hartley’s 1914 solo show at Alfred Stieglitz’s Gallery 291 in New York.

The outbreak of World War I forced Rönnebeck to return to Germany where he fought on the front lines. He was wounded twice and was awarded the Iron Cross by Kaiser Wilhelm II. Arnold Rönnebeck’s cousin was Lieutenant Karl von Freyburg, whom Hartley would fall in love with and follow from Paris to Berlin.[5] Freyburg was killed in combat in October 1914, and Hartley would create Portrait of a German Officer (1914) as a tribute to Freyburg.[6]

In 1920 and 1921, Rönnebeck traveled around Italy with German poets Max Sidow and Theodor Daubler. Upon his return to Berlin, he executed first lithographs depicting Positano, Italy.

Migration to America

In 1923 Rönnebeck arrived in the US, initially settling in Washington, DC, staying with the family of his former fiancée, opera singer Alice Miriam Pinch. He lectured on modern art at the Art Center Gallery and exhibited at the Corcoran. He moved to New York City in 1924. In New York, he was immediately welcomed into Stieglitz’s circle[2] of American avant-garde artists that included Arthur Dove, John Marin, Georgia O'Keeffe, Marsden Hartley and Charles Demuth. Rönnebeck wrote a catalogue essay for the landmark exhibition, Alfred Stieglitz Presents Seven Americans at the Anderson Gallery in 1925.[7] Rönnebeck was a prolific writer and art critic and wrote numerous essays and articles about art throughout his career.[8] The lithographs Rönnebeck made in New York are among his better known works. They borrow from the precisionism movement and show a fascination with the skyscraper and the landscape of the city, what Rönnebeck termed as "living cubism."[9] The Weyhe Gallery, directed by Carl Zigrosser, gave Rönnebeck his first solo show in April 1925 and represented him for the rest of his life. . Fourteen of the works in the 1925 Weyhe show were exhibited in April 1926 at the Fine Arts Gallery in San Diego, California[10] and in June 1926 at the Los Angeles Museum of Art[11] (later re-named LACMA).

In the summer of 1925, Rönnebeck traveled to Taos, New Mexico to visit his friend Mabel Dodge Luhan at her artists' enclave.[2] The visit had several important consequences including exposing Rönnebeck to the desert landscape and the Indigenous peoples of New Mexico, which subsequently became recurrent themes in Rönnebeck’s work, and, Rönnebeck's introduction to Louise Emerson (1901–1980). Emerson was a painter from Philadelphia who had studied with Kenneth Hayes Miller. Rönnebeck and Emerson were married in March 1926 in New York.[12] He would return to Santa Fe frequently between 1927 and 1929, working with architect John Gaw Meem to complete the relief sculptures for the renovation of the La Fonda Hotel. His series of terra cotta panels were inspired by the ceremonial dances of the Pueblo Indians, including Buffalo, Eagle, Deer, Corn, Shalako and Peace Dances.[13] He worked with Meem a second time, in 1936, this time producing three aluminum relief panels depicting Pueblo and Hopi Indian Kachina masks, in the auditorium of the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center.

Move to Denver

In May 1926, Rönnebeck gave a lecture at the fledgling Denver Art Museum while he and his new wife were traveling to California on their honeymoon. While visiting the museum, Rönnebeck was offered the position of Art Director, which he accepted. He served in this capacity from 1926 to 1931,[2] where he encouraged development of the museum's collection of American Indian art and the curation of modernist art exhibitions. The couple became involved in the local Denver art scene, being welcomed into a community of artists that included Allen True, John E. Thompson, Ethel and Jenne Magafan, Frank Mechau, Vance Kirkland, Frank Vavra, Marion Buchan, Elisabeth Spalding, and others. In addition to his work at the museum, Rönnebeck wrote a weekly art column in the Rocky Mountain News. Rönnebeck continued making lithographs, mainly of the Colorado landscape, mining towns and New Mexico. He received numerous commissions in Denver and the surrounding areas. He, along with Robinson and True, was an active member of Denver's Cactus Club.

Rönnebeck participated in the 1934 World's Fair in Chicago, entitled Century of Progress Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture, June 1 to November 1, 1934. His 1921 brass sculpture, Dancer, was loaned by the Weyhe Gallery, in New York.[14]

Rönnebeck was an amateur actor and music enthusiast and became very involved with the renovation of the Central City Opera House in the historic mining town of Central City, Colorado. He performed with the Central City Opera in their presentation of The Merry Widow with Natalie Hall, Gladys Swarthout and Richard Bonelli. Rönnebeck gained American citizenship in 1933.[15] His lithograph, Yacht Races, was also part of the painting event in the art competition in the Graphic Arts Section at the 1936 Summer Olympics.[16]

Arnold and Louise Rönnebeck had two children, Arnold and Ursula. He died of throat cancer in 1947[2] at the age of 62.

Notable Public Sculptures

- Series of terra cotta panels depicting Pueblo Indian ceremonial dance themes; La Fonda Hotel, Santa Fe, completed in 1929.

- The History of Money; Colorado Business Bank, Denver, 1929.

- Madonna and Child Reredos; Cathedral of St. John in the Wilderness, Denver, 1927.

- The Ascension; Church of the Ascension, Denver, 1931.

- Three panels in aluminum; Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center Auditorium, Colorado Springs, 1936.

- Trio and Tone Shapes, Robert and Judi Newman Center for Performing Arts, Denver, 1937 plaster, 2007 two posthumous castings in bronze.

Notable Portrait Sculptures

Marsden Hartley, bronze, 1912. Location: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

Charles Demuth, plaster, 1912. Location: Presumed lost.

Stefan George, plaster, c1921. Location unknown.

Melchior Lechtor, plaster, c1920s. Location unknown.

Hans Sidow, plaster, c1921. Location: private collection.

George Antheil, plaster, 1923. Location: private collection.

Marsden Hartley, Man and Soul (two masks), bronze, 1923. Location: Soul, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT. Man, location unknown.

Marsden Hartley, head, bronze, 1923. Location: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

Marsden Hartley, bust, plaster, 1923. Location: Frederick Weisman Museum, Minneapolis, MN.

Georgia O’Keeffe, bronze 1924. Location: Denver University, Denver, CO.

Pierre Coalfleet, aka Frank Cyril Shaw Davison, bronze, 1925. Location: private collection.

Ananda Coomaraswamy, plaster, 1929. Location: Kirkland Museum of Fine and Decorative Art, Denver, CO.

Carl Sandburg, plaster, c1930s. Location: Hirschorn Museum and Sculpture Museum, Washington, DC.

Allen Tupper True, plaster, c1930s. Location: Private collection.

Self-portrait, plaster, 1947. Location: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

Notes

- ↑ New York Times, November 16, 1947

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Finding Aid". Arnold Rönnebeck and Louise Emerson Rönnebeck papers, 1884-2002. Archives of American Art. 2006. Retrieved 11 Jul 2011.

- ↑ Gertrude Stein (1933).The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. The Literary Guild, 122.

- ↑ Sanchez, Pierre. Dictionnaire du Salon d’Autumne : Répertoire des Exposants et Liste des œuvres Présentées, 1903-1945. L'Echelle de Jacob (2006), Page 1193.

- ↑ "An Artist's Restless Search for Love, and a Place in the World". Art review. New York Times. 2003. Retrieved 11 Jul 2011.

- ↑ Ken Gonzales-Day (2002). "Hartley, Marsden". glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 11 Jul 2011.

- ↑ Barbara Buhler Lynes (1989)O'Keeffe, Stieglitz, and the Critics, 1916-1929U.M.I Research Press, 91

- ↑ See Arnold Rönnebeck (October 1925). "Bourdelle Speaks to his Pupils: From a Paris Diary,"The Arts 8, no. 4. and Rönnebeck (Winter 1945). "Gertrude Was Always Giggling: Memories of Gertrude Stein, Picasso and Others." Books Abroad 19, no. 1.

- ↑ Viktor Flambeau, Washington Herald, 1 June 1924.

- ↑ San Diego Sun, April 25, 1926

- ↑ Arnold Rönnebeck and Louise Emerson Ronnebeck Papers 1884-2002]. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Museum.

- ↑ Lois Rudnick, Utopian Vistas: The Mabel Dodge Luhan House and the American Counter Culture (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996),

- ↑ Berke, Arnold. Mary Colter: Architect of the Southwest, Princeton Architectural Press, New York, 2002.

- ↑ Catalogue of a Century of Progress Exhibition of Paintings and Sculpture 1934, published by the Art Institute of Chicago, 1934, page 92

- ↑ National Archives at Denver; Broomfield, Colorado; Naturalization Records, Colorado, 1876-1990; ARC Title: Naturalization Case Files, 1876 - 1947; NAI Number: 649183; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685 - 2009; Record Group Number: 21

- ↑ "Arnold Rönnebeck". Olympedia. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

Bibliography

- Chambers, Marlene. The First 100 Years: Denver Art Museum. Seattle: Marquand Books, Inc. (1996).

- Fahlman, Betsy. Works on Paper: Prints and Drawings by Arnold Rönnebeck. New York: Conner-Rosenkranz (1998).

- Groff, Diane Price. Arnold Rönnebeck: An Avant-Garde Spirit in the West. M.A. Thesis University of Denver (1991).

- Kornhauser, Elizabeth Mankin.Marsden Hartley. New Haven: Yale University Press (2003).

- Kunin, Jack Henry. “Impressions of a Renaissance: The Artists of Denver National Bank.” Colorado Heritage Summer (2002).

- Schlosser, Elizabeth. Modern Sculpture in Denver (1919-1960): Twelve Denver Sculptors. Glendale: Ocean View Books (1995).

External links

- The Art of Arnold Ronnebeck

- Arnold Ronnebeck Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

- Arnold Rönnebeck and Louise Emerson Ronnebeck Papers 1884-2002. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Museum.