Arthur Dodd (December 1919 in Northwich, Cheshire – 17 January 2011) served in the British Army during World War II. After being captured at Tobruk, he became a Prisoner of War and was imprisoned at E715, an Allied POW camp attached to Auschwitz III (Monowitz), a sub-camp of the notorious Auschwitz.[1]

Biography

Early life

Dodd's father served in the British Army during the Boer War and was a Sergeant during World War I when he was captured. Dodd left school in 1934 aged 15, and became an apprentice mechanic for a motor transport company in his native Northwich, moving to the Weaver Navigation Company in 1937. In September 1938, he nearly lost his left foot when it became trapped between a ramp and a turning wheel. He received extensive physiotherapy for his injuries, but still only received a rating of 'B2' when he tried to enlist into the Army, too low to allow him to join up. However, as he had an HGV licence, he was permitted to enlist as a military driving instructor[1] for the Royal Army Service Corps.

Military service

At the beginning of World War II, Dodd served as a volunteer in France and was involved in the Dunkirk evacuation. Later, he was posted to North Africa and was in action at Tobruk. After Tobruk, Dodd, and an injured colleague, were captured by the enemy at Badir in the Western Desert. After being held in a number of ordinary Italian POW camps, in 1943, he was transferred to Auschwitz III (Monowitz) labour camp, only five miles from the better-known extermination camp of Auschwitz II (Birkenau). Monowitz was under the direction of the industrial company IG Farben, who were building a Buna (synthetic rubber) and liquid fuel plant there, and housed over 10,000 Jewish slave labourers, as well as PoWs and forced labourers from all over occupied Europe.[1]

Auschwitz III (Monowitz)

When Dodd and the POWs disembarked they noticed dozens of bundles of clothing that had just been left by the rail tracks.[2] As they were marched to the concentration camp and factory where they would be working, Dodd tells of a teenage Jewish girl, stripped to the waist, who was being savagely whipped by an SS officer. Dodd and the other POWs attempted to get between him and the bleeding girl. The SS officer pulled out his pistol and threatened to shoot Dodd, who was at the front, if he interfered further. A Wehrmacht soldier warned Dodd that he meant what he said. The British troops stepped aside and the officer resumed beating the girl.[1][2]

The filth of Camp E715,[3] with its accompanying smell of burning flesh from the crematorium at nearby Auschwitz II, was to be Dodd's home for the next 14 months. During his imprisonment in Camp E715, Dodd said he witnessed the mistreatment and killing of Jewish inmates at the camp by their SS guards, including Jews hanging from the gallows in Auschwitz I and several pushed off high scaffolding.[1]

Some of the British POWs frequently put themselves in danger to try to get any scraps of food they could spare to the prisoners in the Jewish section. Others refused to help, believing that the Jewish inmates were simply being rightfully punished for some crime they must have committed. Forced to work, many POWs deliberately sabotaged the pipes they were working on by placing stones or blank flanges into the pipes. Suspicious, on one occasion, a German engineer ordered a pressure test on the pipes. Horrified, the POWs knew that not one pipe would pass such a test and realised that they would be promptly shot. As the test was being prepared, the air raid siren went off and they were ordered into the shelters. Dodd later said:

"We knew that they had found out what we had done. They had us lined up against a wall to shoot us as soon as the pipes failed the test. I had just said a prayer, when the air-raid siren went and everyone, guards and prisoners, dived into the air raid shelters. We heard a bomb fall and when the raid was over we saw that the only bomb to hit the factory had blown out the wall where the pipes were. God was looking after us that day. Maybe John Wesley had a hand in it as well."

When the air raid ended, the British troops were led out of the shelter and, to their relief, saw that the only building hit by a bomb had been the BAU 38; the place where the pressure test was to take place. All of the pipes had been destroyed.[1]

During a further air raid on 20 August 1944, Dodd and other POWs were in a shelter which was hit by a bomb, killing 38 British POWs and injuring Dodd and others. These 38 POWs are commemorated on a plaque which was unveiled on the 60th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, in 2005. Their remains were interred in the Kraków Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery.[1]

In late 1944, the British POWs heard a noise outside their huts. On going outside to investigate, they saw about a thousand Jews, old men, women and children, walking towards Auschwitz II on the other side of the perimeter wire. The children were playing and singing as they passed. Once they had gone, the men returned to their huts in silence. They had been told in the past of the fate of such columns of walking Jews.[1]

Freedom

On 23 January 1945, four days before Auschwitz was liberated by the Red Army, in the coldest winter Poland had experienced for years, the British PoWs were given the option by their German guards to either start walking east towards the Russians or west towards the Americans. Dodd chose the latter. In the weeks of walking during this 'Death March', when the temperature often dropped to minus 25°C, the walking men froze, and some starved to death. As they walked, they passed the partially snow-covered bodies of hundreds of dead Jews, some of whom had died from cold or their exertions, while others had been shot.[1]

Those PoWs who had greatcoats, shared them, and they slept huddled together to stave off the cold. In the towns they passed, they witnessed the slaughter by the retreating Nazis. On reaching Regensburg in Germany, Dodd and his colleagues were finally liberated.[2]

After the War, Dodd worked for British Waterways in Northwich. On 21 September 1946, he married Olwen. They had two children, six grandchildren and ten great grandchildren.

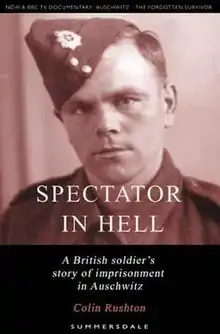

Spectator in Hell

Dodd's story is told in the book Spectator in Hell by Colin Rushton, first published by Pharaoh Press in 1998 and subsequently republished by Summersdale Publishers Ltd in 2001 and 2005. His story was also told in the television documentaries Satan at His Best (1995)[4] and in the BBC's Auschwitz: The Forgotten Witness (1997).[5][6] In the latter programme, Dodd returned to Auschwitz to find the location of Camp E715, and tried unsuccessfully to gain admission to the IG Farben plant to claim the 14 months backwages he said they owed him for his forced wartime labour there.

Decline and death

In November 2009 it was reported in the Wirral News that, aged 90, Dodd was battling with Alzheimer's disease and required full-time care at a care home in Cheshire. A campaign was launched to raise the £500 a week needed to cover the cost of his care.[7] He died in the early hours of 17 January 2011 aged 91.[8]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Rushton, Colin 'Spectator in Hell' Pharaoh Press (1998)

- 1 2 3 Dodd on the Axis History Forum website

- ↑ The British Connection to Auschwitz: Work Camp E715 and the IG Farben Chemical Plant, 1943-1945

- ↑ Wollheim Memorial website

- ↑ Dodd on ABC TV Online

- ↑ "HOMEGROUND [BBC2, 1997- ]: AUSCHWITZ - THE FORGOTTEN WITNESS", British Film Institute

- ↑ 'Campaign to help Auschwitz death camp survivor' 8 June 2009

- ↑ Gary Porter (27 January 2011). "Auschwitz prisoner of war survivor and Cuddington resident Arthur Dodd dies, aged 91". Chester Chronicle. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

External links

- Dodd and Auschwitz

- Dodd and the British Connection to Auschwitz

- Dodd in Auschwitz: The Forgotten Witness

- Dodd on Aish.com

- Dodd in the Daily Express 7 September 2007

- Dodd in Satan at His Best

- Review of Spectator in Hell in the New Statesman 26 March 2001