| |

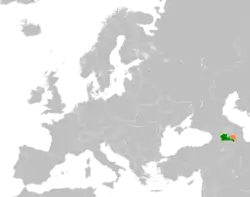

Armenia |

Republic of Artsakh |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Permanent Representation of the NKR in Armenia | None |

Armenia–Artsakh relations are the foreign relations between the unrecognized Republic of Artsakh and Armenia. The Republic of Artsakh controls most of the territory of the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (before the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, it also controlled some of the surrounding area).[1] Artsakh has very close relations with Armenia. It functions as a de facto part of Armenia.[2][3][4][5][6][7] A representative office of Nagorno-Karabakh exists in Yerevan.[8]

History

Kingdom of Artsakh

The House of Khachen ruled the medieval Kingdom of Artsakh in the 11th century as an independent kingdom under the protectorate of the Bagratid Kingdom of Armenia.

Soviet era unification proposals

Under the Soviet Union, the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast was an autonomous oblast within the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic, whose population was mostly ethnic Armenians.[9][10][11] On this basis, there were many calls for internal unification with the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic.[12]

Early 20th-century history

Although the question of Nagorno-Karabakh's status did not become a major public issue until the mid-1980s, Armenian intellectuals, Soviet Armenian and Karabakh Armenian leadership periodically made appeals to Moscow for the region's transfer to Soviet Armenia.[13] In 1945, the leader of Soviet Armenia Grigory Arutinov appealed to Stalin to attach the region to Soviet Armenia, which was rejected.[13]

Late 20th-century history

After Stalin's death, Armenian discontent began to be voiced. In 1963, around 2,500 Karabakh Armenians signed a petition calling for Karabakh to be put under Armenian control or to be transferred to Russia. The same year saw violent clashes in Stepanakert, leading to the death of 18 Armenians. In 1965 and 1977, there were large demonstrations in Yerevan calling to unify Karabakh with Armenia.[12]

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev came to power as the new general secretary of the Soviet Union and began implementing plans to reform the Soviet Union, encapsulated in two policies: perestroika and glasnost. While perestroika had to do with structural and economic reform, glasnost or "openness" granted limited freedom to Soviet citizens to express grievances about the Soviet system and leaders. Capitalizing on this, the leaders of the Regional Soviet of Karabakh decided to vote in favor of unifying the autonomous region with Armenia on 20 February 1988.[14]

Karabakh Armenian leaders complained that the region had neither Armenian language textbooks in schools nor in television broadcasting,[15] and that Azerbaijan's Communist Party General Secretary Heydar Aliyev had attempted to extensively "Azerify" the region, increasing the influence and number of Azerbaijanis living in Nagorno-Karabakh, while at the same time reducing its Armenian population. Aliyev stepped down as General Secretary of Azerbaijan's Politburo, in 1987.[16] The Armenian population of Karabakh had dwindled to nearly three-quarters of the total population by the late 1980s.[17]

The movement was spearheaded by popular Armenian figures.[18] In February 1988, Armenians began protesting and staging workers' strikes in Yerevan, demanding unification with the enclave.[19]

On 20 February 1988, the leaders of the regional Soviet of Karabakh voted in favour of unifying the autonomous region with Armenia[20] in a resolution reading:

Welcoming the wishes of the workers of the Nagorny Karabakh Autonomous Region to request the Supreme Soviets of the Azerbaijani SSR and the Armenian SSR to display a feeling of deep understanding of the aspirations of the Armenian population of Nagorny Karabakh and to resolve the question of transferring the Nagorny Karabakh Autonomous Region from the Azerbaijani SSR to the Armenian SSR, at the same time to intercede with the Supreme Soviet of the USSR to reach a positive resolution on the issue of transferring the region from the Azerbaijani SSR to the Armenian SSR.[21]

On 10 March, Gorbachev stated that the borders between the republics would not change, in accordance with Article 78 of the Soviet constitution.[22] Gorbachev said that several other regions in the Soviet Union were yearning for territorial changes and redrawing the boundaries in Karabakh would thus set a dangerous precedent. The Armenians viewed the 1921 Kavburo decision with disdain and felt they were correcting a historical error through the principle of self-determination (a right also granted in the constitution).[22]

On 23 March 1988, the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union rejected the demands of Armenians to cede Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia. Troops were sent to Yerevan to prevent protests against the decision. Gorbachev's attempts to stabilize the region were to no avail, as both sides remained equally intransigent. In Armenia, there was a firm belief that what had taken place in the region of Nakhichevan would be repeated in Nagorno-Karabakh: prior to its absorption by Soviet Russia, it had a population which was 40% Armenian;[23] by the late 1980s, its Armenian population was virtually non-existent.[24]

Post-Soviet era

First Nagorno-Karabakh War

After independence from the Soviet Union, the newly created Republic of Armenia publicly denied any involvement in providing any weapons, fuel, food, or other logistics to secessionists in Nagorno-Karabakh. President Levon Ter-Petrosyan later admitted to supplying them with logistical supplies and paying the salaries of the separatists, but denied sending any of its own men into combat.

The only land connection Armenia had with Karabakh was through the narrow, mountainous Lachin corridor which could only be reached by helicopters.

Second Nagorno-Karabakh war and peace negotiations

In 2020, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict boiled over into a war. Armenia once again supported Artsakh during the conflict against Azerbaijan.[25] At the end of the conflict, a peace deal was signed which served as a victory for Azerbaijan. Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan called it "incredibly painful both for me and both for our people".[26]

In April 2022, during peace negotiations with Azerbaijan, Armenia signaled willingness to hand control of the Nagorno-Karabakh region over to Azerbaijan. Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan stated that the international community had pressured Armenia to "lower the bar a bit" on Artsakh's status. This drew immediate criticism from Artsakh officials. Artsakh's Foreign Minister David Babayan stated that "Any attempt to incorporate Artsakh into Azerbaijan would lead to bloodshed and the destruction of Artsakh".[27] In a unanimous resolution, the parliament of Artsakh demanded that Armenia "abandon their current disastrous position."[28]

A politician from the Askeran district of Artsakh floated the idea of a referendum to join Russia, saying that this would "avoid physical annihilation" and "save the remains of the shattered Artsakh".[27]

In May 2023, Armenia stated that it is willing to recognize Karabakh as a part of Azerbaijan.[29]

Resident diplomatic missions

- Artsakh also has an representative office in Yerevan.

See also

References

- ↑ "Official website of the President of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic. General Information about NKR". President.nkr.am. 1 January 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ↑ Hughes, James (2002). Ethnicity and Territory in the Former Soviet Union: Regions in Conflict. London: Cass. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-7146-8210-5.

Indeed, Nagorno-Karabakh is de facto part of Armenia.

- ↑ Mulcaire, Jack (9 April 2015). "Face Off: The Coming War between Armenia and Azerbaijan". The National Interest.

The mostly Armenian population of the disputed region now lives under the control of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, a micronation that is supported by Armenia and is effectively part of that country.

- ↑ "Armenia expects Russian support in Karabakh war". Hürriyet Daily News. 20 May 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

While internationally recognized as Azerbaijani territory, the enclave has declared itself an independent republic but is administered as a de facto part of Armenia.

- ↑ Central Asia and The Caucasus, Information and Analytical Center, 2009, Issues 55-60, Page 74, "Nagorno-Karabakh became de facto part of Armenia (its quasi-statehood can dupe no one) as a result of aggression."

- ↑ Deutsche Gesellschaft für auswärtige Politik, Internationale Politik, Volume 8, 2007 "... and Nagorno-Karabakh, the disputed territory that is now de facto part of Armenia ..."

- ↑ Cornell, Svante (2011). Azerbaijan Since Independence. New York: M.E. Sharpe. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-7656-3004-9.

Following the war, the territories that fell under Armenian control, in particular Mountainous Karabakh itself, were slowly integrated into Armenia. Officially, Karabakh and Armenia remain separate political entities, but for most practical matters the two entities are unified.

- ↑ "Representations of the Nagorno Karabakh Republic". Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ↑ Ardillier-Carras, Françoise (2006). "Sud-Caucase : conflit du Karabagh et nettoyage ethnique" [South Caucasus: Nagorny Karabagh conflict and ethnic cleansing]. Bulletin de l'Association de Géographes Français (in French). 83 (4): 409–432. doi:10.3406/bagf.2006.2527.

- ↑ "UNHCR publication for CIS Conference (Displacement in the CIS) – Conflicts in the Caucasus". Unhcr. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

- ↑ Yamskov, A. N. (1991). Ethnic Conflict in the Transcausasus: The Case of Nagorno-Karabakh. Vol. 20. p. 659.

{{cite book}}:|periodical=ignored (help) - 1 2 Christoph Zürcher, The Post-Soviet Wars: Rebellion, Ethnic Conflict, and Nationhood in the Caucasus (New York: New York University Press, 2007), pp. 154

- 1 2 de Waal 2003, pp. 137–140.

- ↑ Gilbert, Martin (2001). A History of the Twentieth Century: The Concise Edition of the Acclaimed World History. New York: Harper Collins. p. 594. ISBN 0-0605-0594-X.

- ↑ Brown, Archie (1996). The Gorbachev Factor. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 262. ISBN 0-19-288052-7.

- ↑ (in Russian) Anon. "Кто на стыке интересов? США, Россия и новая реальность на границе с Ираном" (Who is at the turn of interests? US, Russia and new reality on the border with Iran Archived 24 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine). Regnum. 4 April 2006.

- ↑ Lobell, Steven E.; Philip Mauceri (2004). Ethnic Conflict and International Politics: Explaining Diffusion and Escalation. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. p. 58. ISBN 1-4039-6356-8.

- ↑ de Waal 2003, p. 23.

- ↑ de Waal 2003, p. 30.

- ↑ Gilbert, Martin (2001). A History of the Twentieth Century: The Concise Edition of the Acclaimed World History. New York: Harper Collins. p. 594. ISBN 0-06-050594-X.

- ↑ de Waal 2003, p. 10.

- 1 2 Rost, Yuri (1990). The Armenian Tragedy: An Eye-Witness Account of Human Conflict and Natural Disaster in Armenia and Azerbaijan. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-312-04611-1.

- ↑ Hovannisian, Richard G. (1971). The Republic of Armenia: The First Year, 1918–1919, Vol. I. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 91. ISBN 0-520-01984-9.

- ↑ Melkonian, Markar (2005). My Brother's Road, An American's Fateful Journey to Armenia. New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-85043-635-5.

- ↑ Joffre, Tzvi. "Russian MOD: Azerbaijani forces broke ceasefire for 2nd time in a week". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- ↑ "Armenia, Azerbaijan and Russia sign Nagorno-Karabakh peace deal". BBC. 10 November 2020.

The BBC's Orla Guerin in Baku says that, overall, the deal should be read as a victory for Azerbaijan and a defeat for Armenia.

- 1 2 Mejlumyan, Ani (2022-04-16). "Officials In Karabakh Break With Armenia Over Negotiations". Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- ↑ Badalian, Susan; Khulian, Artak (2022-04-15). "Karabakh Leaders Warn Pashinyan". The Armenian. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- ↑ "Armenia 'Ready To Recognize' Karabakh As The Territory Of Azerbaijan, Armenian PM Pashinyan Hints At Ending War". Eurasiantimes.com. 22 May 2023.

Bibliography

- de Waal, Thomas (2003). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 9780814719459.