| Dhandayuthapani Swamy Temple | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) View of the entrance | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Hinduism |

| District | Dindigul |

| Deity | Dhandayuthapani (Murugan) |

| Festivals |

|

| Location | |

| Location | Palani |

| State | Tamil Nadu |

| Country | |

Location in Tamil Nadu, India | |

| Geographic coordinates | 10°26′20″N 77°31′13″E / 10.438805°N 77.520261°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Tamil architecture |

| Creator | Bogar |

| Website | |

| palanimurugan | |

Arulmigu Dhandayuthapani Swamy Temple[1][2] is third of the Six Abodes of Murugan (Aarupadai veedugal). It is located in the city of Palani, Dindigul district, 100 kilometres (62 mi) southeast of Coimbatore and northwest of Madurai in the foothills of the Palani Hills, Tamil Nadu, India. Known as Thiruaavinankudi in the old Sangam literature of Thirumurugatrupadai, Palani temple is considered synonymous with Panchamritam, a sweet mixture made of five ingredients.

As per Hindu legendary beliefs, Sage Narada visited the celestial court of Shiva at Mount Kailash to present to him a fruit, the gnana-palam (literally, the fruit of knowledge). He decided to award it to whichever of his two sons who first encircle the world thrice. Accepting the challenge, Murugan started his journey around the globe on his mount peacock. However, Ganesha, who surmised that the world was no more than his parents Shiva and Shakti combined, circumambulated them and won the fruit. Murugan was furious and felt the need to get matured from boyhood and hence chose to remain as a hermit in Palani. The idol of the Muruga in Palani was created and consecrated by sage Bogar, one of Hinduism's eighteen great Siddhars, out of an amalgam of nine poisonous herbs or Navapashanam.

Other than the steps and sliding elephant way, there is a winch and rope car service used for transportation of devotees uphill. Six poojas are performed from 6.00 a.m. to 8.00 p.m and special poojas on festival days in the temple, when it is open from 4.30 a.m.

As of 2016, the temple was the richest among temples in the Tamil Nadu state with a collection of 33 crore during the period of July 2015 to June 2016. The temple is maintained and administered by the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Department of the Government of Tamil Nadu.[3]

Legend

Sage Narada once visited the celestial court of Shiva at Mount Kailash to present to him a fruit, the gnana-palam (literally, the fruit of knowledge), that held in it the elixir of wisdom. Upon Shiva expressing his intention of dividing the fruit between his two sons, Ganesha and Murugan, the sage counseled against cutting it. He decided to award it to whichever of his two sons first circled the world thrice. Accepting the challenge, Karthikeya started his journey around the globe on his mount peacock. However, Ganesha, who surmised that the world was no more than his parents Shiva and Shakti combined, circumambulated them. Pleased with their son's discernment, Shiva awarded the fruit to Ganesha. When Kartikeya returned, he was furious to learn that his efforts had been in vain. He left Kailash and took up his abode in the Palani hills in South India. It is believed that Karthikeya felt the need to get matured from boyhood and hence chose to remain as a hermit and discarded all his robes and ornaments. He went into meditation to know about himself.[4][5]

As per another legend, once all sages and gods assembled in Kailash, the abode of Shiva. It resulted in the tilting of earth towards one direction. Shiva asked sage Agathiyar to move towards the South to balance the tilt. Agastya employed a demon by name Ettumba to carry two hills in his shoulders to be placed in the South. The demon carried the hills down south and rested in a place. When he tried to lift one of the hills, it did not budge and he found a young man standing at the top of the hill not allowing it to be moved. The demon tried to attack the young man but was defeated. Sage Agastya identified the young man as Murugan (Karthikeya) and asked him to pardon the demon. Murugan readily did so and let the hill remain there at Palani. It is a practice followed in the modern times where people carry milk in both their shoulders as a devotion to please the Lord. The demon carried the other hill to Swamimalai, which is another of the six abodes of Lord Murugan.[4]

History

The idol of the Muruga in Palani was created and consecrated by sage Bogar (Bhoga Muni), one of Hinduism's eighteen great Siddhars out of an amalgam of nine rocks or navapashanam (Pashana in Sanskrit means poison). The legend also holds that the sculptor had to work very rapidly to complete its feature and made it perfect. Later, some people who had access to the deity used hideous chemicals and robbed off the idol's contents greatly damaging the idol and conspirated theories that the sage did not sculpt the outer features well as he did to the face. A shrine to Bhogar exists in the southwestern corridor of the temple, which, by legend, is said to be connected by a tunnel to a cave in the heart of the hill, where Bhogar continues to meditate and maintain his vigil, with eight idols of Muruga.[6]

The deity, after centuries of worship, fell into neglect and was suffered to be engulfed by the forest. One night, Perumal a king of the Chera Dynasty, who controlled the area between the second and fifth centuries A.D., wandered from his hunting party and was forced to take refuge at the foot of the hill. It so befell, that the Subrahmanyan, appeared to him in a dream, and ordered him to restore the idol to its former state. The king commenced a search for the idol, and finding it, constructed the temple that now houses it, and re-instituted its worship. This is commemorated by a small stela at the foot of the staircase that winds up the hill.

Architecture

The idol of the deity is said to be made of an amalgam of nine poisonous substances which forms an eternal medicine when mixed in a certain ratio. It is placed upon a pedestal of stone, with an archway framing it and represents the god Subrahmanya in the form He assumed at Palani - that of a very young recluse, shorn of his locks and all his finery, dressed in no more than a loincloth and armed only with a staff, the dhandam, as befits a monk.[6]

The temple was re-consecrated by the Cheras, whose dominions lay to the west, and the guardian of whose eastern frontier was supposed to be the Kartikeya of Palani. Housed in the garbhagriham, the sanctum sanctorum, of the temple, the deity may be approached and handled only by the temple's priests, who are members of the Gurukkal community of Palani, and hold hereditary rights of sacerdotal worship at the temple. Other devotees are permitted to come up to the sanctum, while the priests' assistants, normally of the Pandāram community, are allowed up to the ante-chamber of the sanctum sanctorum.[6]

The temple is situated upon the higher of the two hills of Palani, known as the Sivagiri. Traditionally, access to it was by the main staircase cut into the hill-side or by the yanai-padhai or elephant's path, used by the ceremonial elephants. Pilgrims bearing water for the ritual bathing of the idol, and the priests, would use another way also carved into the hill-side but on the opposite side. Over the past half-century, three funicular railway tracks have been laid up the hill for the convenience of the pilgrims, and supplemented by a rope-way within the past decade. There are two modes of transport from the foothills to uphill. There is a winch, which operate from 6 a.m. on ordinary days and 4 a.m. during festive occasions. There is another rope car which operates from 7 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. and 1:30 p.m. to 5 p.m. Both winch and the rope car are closed after the Irakkala Pooja at 8 p.m.[7]

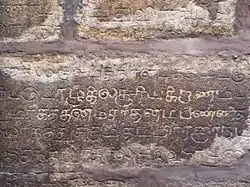

The sanctum of the temple is of early Chera architecture while the covered ambulatory that runs around it bears unmistakable traces of Pandya influence, especially in the form of the two fishes, the Pandyan royal insignia. The walls of the sanctum bear extensive inscriptions in the old Tamil script. Surmounting the sanctum, is a gopuram of gold, with numerous sculptures of the presiding deity, Kartikeya, and gods and goddesses attendant upon him. In the first inner prahāram, or ambulatory, around the heart of the temple, are two minor shrines, one each, to Shiva and Parvati, besides one to the sage Bhogar who is by legend credited with the creation and consecration of the chief idol. In the second precinct, is a celebrated shrine of Ganapati, besides the carriage-house of the Muruga's Golden Chariot.[6]

Worship

The most common form of worship at the temple is the abhishekam - anointment of the idol with oils, sandalwood paste, milk, unguents and the like and then bathing it with water in an act of ritual purification. The most prominent abhishekams are conducted at the ceremonies to mark the hours of the day. These are four in number - the Vizha Poojai, early in the morning, the Ucchikālam, in the afternoon, the Sāyarakshai, in the evening and the Rakkālam, at night, immediately prior to the temple being closed for the day. These hours are marked by the tolling of the heavy bell on the hill, to rouse the attention of all devotees to the worship of the lord being carried out at that hour. On a quiet day, the bell can be heard in all the countryside around Palani. In addition to worship within the precincts of the temple, an idol of the Lord, called the Uthsavamoorthy, is also carried in state around the temple, in a golden chariot, drawn by devotees, most evenings in a year. As of 2016, the temple was the richest among temples in the state with a collection of 33 crore during the period of July 2015 to June 2016.[8]

Religious practices

One of the main traditions of the temple, is the tonsuring of devotees, who vow to discard their hair in imitation of the form that Kartikeya assumed here. Another is the anointing of the head of the presiding deity's idol with sandalwood paste, at night, prior to the temple being closed for the day. The paste, upon being allowed to stay overnight, is said to acquire medicinal properties, and is much sought after and distributed to devotees, as rakkāla chandaṇam.[9] Traditionally, the hill-temple of Palani is supposed to be closed in the afternoon and rather early in the evening to permit the deity to have adequate sleep, being but a child, and therefore, easily tired by the throngs of devotees and their constant importunations. A tradition that is not very well known is that of the Paḷḷi-Arai or bedroom, wherein, each night, the Lord is informed of the status of the temple's accounts for the day, by the custodians of the temple, and then put to sleep to the singing of an ōdhuvār or bard. Devotees carry kavadi, an ornamental mount decked with flowers, glazed paper and tinsel work and wearing ochre clothes themselves on foot from long distances is a commonly followed worship practice.[10]

Panchamirdam (mixture of five) is believed to be a divine mix prepared by Vinayagar at the end of the divine encounter. He mixed honey, dates, banana, raisins and jaggery and distributed it to Shiva Karthikeya. The practice is followed in modern times where the devotees are provided Panchamirdam as a Prasad.[4][11]

Festivals and religious practises

Besides regular services, days sacred to the god Subrahmanyan are celebrated with pomp and splendour every year, and are attended by throngs of devotees from all over the world. Some of these festivals are the Thai-Poosam, the Panguni-Uthiram, the Vaikhashi-Vishakham and the Sura-Samharam. Thai-Poosam, which is considered, by far, the most important festival at Palani, is celebrated on the full moon day of the Tamil Month of Thai (15 January-15 February). Vaiyaapuri nattu Pattakkarar Muthukaali Tharagan gothram pangaalis of Sengunthar Kaikola Mudaliyar have rights to give festival flag for this temple. Because these people are Genealogy of Navaveerargal who helped lord Murugan in surasamharam battle.[12] Pilgrims after first having taken a strict vow of abstinence, come barefoot, by walk, from distant towns and villages. Many pilgrims also bring a litter of wood, called a Kāvadi, borne on their shoulders, in commemoration of the act of the demon Hidumba who is credited by legend with bringing the two hills of Palani to their present location, slung upon his shoulders in a similar fashion. Others bring pots of sanctified water, known as theertha-kāvadi, for the priests to conduct the abhishekam on the holy day. Traditionally, the most honoured of the pilgrims, whose arrival is awaited with anticipation by all and sundry, are the people of Karaikudi, who bring with them the diamond-encrusted vél or javelin, of the Lord from His temple at Karaikudi.[13]

The temple is open from 6.00 a.m. to 8.00 p.m. On festival days the temple opens at 4.30 a.m. There are six poojas performed in the temple, namely, the Vilaa pooja at 6.30 a.m., Siru Kall pooja at 8.00 a.m., Kaala Santhi at 9.00 a.m., Utchikkala Pooja at 12.00 noon, Raja Alankaram at 5.30 p.m., Iraakkaala pooja at 8.00 p.m. The Golden Car can be viewed at 6.30 p.m.[13][14] Temple Golden chariot was first introduced in This temple. Palani Murugan Golden Chariot was donated by V.V.C.R.Murugesa Mudaliar of Sengunthar Kaikola Mudaliyar(Pullikkarar Gothram) from Erode on 17.8.1947. This chariot was made using 4.73 kg of gold 63 kg of silver and diamonds.[15] [16]

Controversy

The original idol of the presiding deity is believed to have been made by Bogar Siddhar using nine highly toxic herbs(navapasanam), which could kill people with its very presence (or close contact). Over the years, some believe that the idol has been wearing away or dissolving, by virtue of its repeated anointment and ritual bathing. However, long-time devotees and priests of the temple maintain that they perceive no visible change. Since Hinduism forbids the worship of an imperfect idol, suggestions have been made, at various points of time, to replace it, cover it, or stop some of the rituals, which could have resulted in its erosion. A new 100 kg idol was consecrated on 27 January 2004, but coming under severe criticism from orthodox believers, was displaced and worship of the existing idol restored, shortly thereafter. During the regime of M.G. Ramachandran, the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu during 1984, attempts were made to replace the idol and also during the first tenure of J. Jayalalithaa during 1994. Both the attempts were withdrawn along with the latest attempt during 2002. The ablution and anointment has been limited to festive days on account of the cracks in the idol of the presiding deity.[17]

In 2003 the temple officials decided to make an idol weighing 200 kg, and chief sculptor Muthiah was roped in. They ended up making a 221 kg idol. Besides, while several kilos of gold were collected to make the idol, this was not found in it when the idol wing police tested it with the help of a team from IIT Madras. The Idol Wing – CID police, which had inquired into irregularities behind making a metal idol in 2004, confirmed on 07/07/2019 that the new idol had been made with the larger ploy of smuggling the 5,000-year-old presiding deity out of the country.[18]

Religious importance

Arunagirinathar was a 15th-century Tamil poet born in Tiruvannamalai. He spent his early years as a rioter and womanizer. After ruining his health and reputation, he tried to commit suicide by throwing himself from the northern tower of Annamalaiyar Temple, but was saved by the grace of god Murugan.[19] He became a staunch devotee and composed Tamil hymns glorifying Murugan, the most notable being Thirupugazh.[20][21] Arunagirinathar visited various Murugan temples and on his way back to Tiruvannamalai, visited Palani and sung praises about Murugan of this temple. He sung the highest number of Thiruppugazh dedicated to this temple.[22] Palani temple is one of the Six Abodes of Murugan and considered one of the most prominent abodes of Muruga.[23]

Notes

- ↑ "Arulmigu Dhandayuthapani Swami Devasthanam, Palani". palani.org. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ↑ "Only Official Website Palani Arulmigu Dhandayuthapaniswamy Temple". palanimurugantemple.org. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ↑ "Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Act, 1959". Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- 1 2 3 Bhoothalingam 2011, pp. 48-52

- ↑ Bhoothalingam, Mathuram (2016). S., Manjula (ed.). Temples of India Myths and Legends. New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. pp. 48–52. ISBN 978-81-230-1661-0.

- 1 2 3 4 V., Meena. Temples in South India. Kanniyakumari: Harikumar Arts. pp. 19–20.

- ↑ "Tourism Palani". Dindigul district administration. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ↑ "Palani temple annual hundi collection touches Rs 33cr". TNN. The Times of India. 27 July 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ↑ Clothey, Fred W. (1972). "Pilgrimage Centers in the Tamil Cultus of Murukan". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. Oxford University Press. 40 (1): 82. JSTOR 1461919.

- ↑ Mohamed, N.P.; A.J., Thomas (2003). "N.P. Mohamed in Conversation with A.J. Thomas". Indian Literature. Sahitya Akademi. 47 (1): 147. JSTOR 23341738.

- ↑ S.R., Ramanujam (2014). The Lord of Vengadam. PartridgeIndia. p. 185. ISBN 9781482834628.

- ↑ "பழனியில் தைப்பூசத் திருவிழா! கொடியேற்றத்துடன் தொடங்கியது!!". 2 February 2020.

- 1 2 K.S., Krishnan (21 January 2005). "The special charm of Palani". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 9 July 2008. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ↑ "Palani temple introduces online facility". The Hindu. 5 January 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ↑ http://palani.in/palani-murugan-temples/palani-murugan-golden-chariot%3famp

- ↑ "Palani Devasthanam facilities".

- ↑ N., Sathiya Moorthy (20 November 2002). "Ageing Palani deity in midst of controversy". Chennai: Rediff. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ↑ "New idol made in Palani temple with ploy to smuggle out presiding deity". Palani: TOI. 9 July 2019. Archived from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ↑ V.K., Subramanian (2007). 101 Mystics of India. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. p. 109. ISBN 978-81-7017-471-4.

- ↑ Aiyar, P.V.Jagadisa (1982), South Indian Shrines: Illustrated, New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, pp. 191–203, ISBN 81-206-0151-3

- ↑ Zvelebil, Kamil (1975), Tamil literature, Volume 2, Part 1, Netherlands: E.J. Brill, Leiden, p. 217, ISBN 90-04-04190-7

- ↑ Zvelebil 1991, p. 53

- ↑ Economic Reforms and Small Scale Industries. Concept Publishing Company. 2009. p. 25. ISBN 9788180694493.

References

- Bhoothalingam, Mathuram (2011). S. Manjula (ed.). Temples of India - Myths and legends. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. ISBN 978-81-230-1661-0.

- Zvelebil, Kamil V. (1991). Tamil traditions on Subramanya - Murugan (1st ed.). Chennai, India: Institute of Asian Studies.