| Aust | |

|---|---|

Aust Church | |

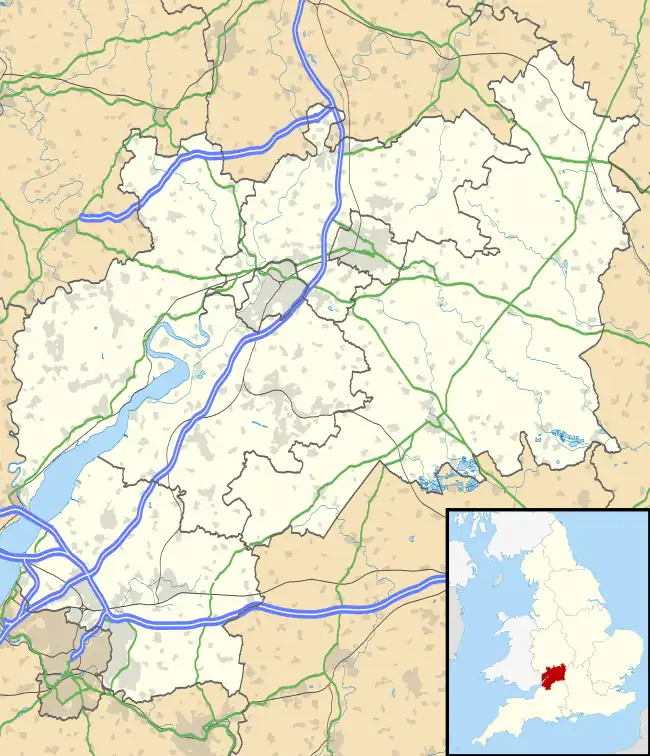

Aust Location within Gloucestershire | |

| Population | 532 (2011)[1] |

| Civil parish |

|

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Bristol |

| Postcode district | BS35 |

| Police | Avon and Somerset |

| Fire | Avon |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

Aust is a small village in South Gloucestershire, England, about 10 miles (16 km) north of Bristol and about 28 miles (45 km) south west of Gloucester. It is located on the eastern side of the Severn estuary, close to the eastern end of the Severn Bridge which carries the M48 motorway. The village has a chapel, a church and a public house. There is a large area of farmland on the river bank, which is sometimes flooded due to the high tidal range of the Severn. Aust Cliff, above the Severn, is located about 0.5 miles (0.80 km) from the village.[2] The civil parish of Aust includes the villages of Elberton and Littleton-upon-Severn.

History

Overview

Aust, on the River Severn, was at one end of an ancient Roman road that led to Cirencester.[3] Its name, Aust, may be one of the very few English place-names to be derived from the Latin Augusta.[4][5][nb 1]

The name of Aust is recorded in 793 or 794 as Austan (terram aet Austan v manentes) when it was returned to the Church of Worcester after having been taken by King Offa's earl, Bynna.[6][7] In Domesday, Aust Cliff was recorded as Austreclive, "clive" being a Middle English spelling of cliff.[4][6] and the estate was held by Turstin FitzRolf in 1066.[8] In 1368 the area was called Augst, "the short unmistakable form of Augusta.[4]

Historically Aust was a village and manor in the parish of Henbury.[4]

Aust church

It was reported as a part of the church of Worcester's Westbury on Trym estate in the Domesday book.[7][nb 2] About 1100 Winebaud de Ballon gave the church to the Abbey of St Vincent, Le Mans.[4] In the 14th century, the chapel at Aust was part of the Church of Westbury.[9]

The Lollard theologian John Wycliffe (died 1384) is by tradition said to have been prebend of Aust and to have preached there, yet Baker (1901) was unable to find any record of such an appointment in the diocesan registers at Worcester, which see held Aust for many centuries.[10]

The existing church is dedicated to St John, and is mostly built in the Perpendicular Gothic style. The timber roofs and octagonal stone font date from the 15th century, and the western church tower, with an embattled parapet, was probably rebuilt in the Tudor period. The church contains several 18th-century marble memorial tablets, the earliest dated 1704 to Sir Samuel Astry. The whole church was restored in 1866 by the firm of Pope & Bindon.[11]

Aust manor

The estate at Aust was held from the Bishop of Worcester as part of the extensive feudal barony of Turstin FitzRolf who had acted as standard-bearer to William the Conqueror at the Battle of Hastings in 1066.[8] FitzRolf's properties in Gloucestershire were held in capite,[12] including Aust, reverted to the Crown and then were granted to Wynebald de Ballon from Maine. Wynebald had a holding at Caerleon on the River Usk near the manor of his brother Hamelin de Ballon of Abergavenny. Both brothers made significant donations to the Abbey of St Vincent at Le Mans, including Wynebald's donation of the church of Aust.[13]

A daughter of de Ballon married a man named de Newmarch, their son Henry held the estate of Aust in 1166. John, his son and heir, next held Aust. One of John's daughters and co-heiress married Ralf Russell of Kingston Russell, who then held the estate.[12]

It passed in moiety through generations of the Russell and then Dennis families, through Margret Russell who married Sir Gilbert Denys (died 1422) to her grandson Walt Dennis. The moiety was purchased by the Astry family,[14] The other moiety of Aust was held by Roger de Acton and was eventually sold to the Astry family.[15] Reportedly it came into the Astry family in 1652.[16] It was passed through several generations and was sold several times. In 1801, it was owned by Sacheverell Sitwell of Derbyshire.[15]

Services and facilities

The village is within a short walking distance of 24hr shops at nearby Severn View services (originally known as Aust Services), a small motorway service area operated by Moto on the M48 motorway near the Severn Bridge. There are also Burger King, and Costa Coffee located there.[17] The main building is a two-storey timber and stone construction.[11] The service area was listed as the last-known (February 1995) whereabouts of former Manic Street Preachers band member Richey Edwards, officially presumed deceased since 2008.[18]

The Severn Bridge, a suspension bridge opened as part of the M4 motorway (later renamed the M48) in 1966, crosses the Severn estuary between Aust and Beachley.[11] It was the first Severn road crossing south of Gloucester, and took five years to construct at a cost of £8 million.[19] It replaced the Aust Ferry.

The Aust Ferry passage across the Severn estuary between Aust and Beachley – later known as the Old Passage – was used from antiquity. In the 12th century, responsibility was granted to the monks of Tintern Abbey, and it continued to operate in subsequent centuries. From 1827, a regular steamboat ferry service was established, but it lost much of its trade when a rival service was set up downstream at New Passage in 1863, and when the Severn rail tunnel was opened in 1886. The growth of road traffic led to the re-establishment of a ferry between Aust and Beachley in 1926, carrying no more than 17 vehicles each time. Bob Dylan was photographed in 1966 standing outside the ferry ticket office, with the almost-completed Severn Bridge behind; the photo was used to publicise Martin Scorsese's film No Direction Home.[20] The ferry service closed when the Severn Bridge was opened in September 1966.

See also

Notes

- ↑ An alternate theory is that it may be named after St Augustine's Oak, but that theory is discounted as a "weakened dative case", due to location and dates of name use.[4]

- ↑ Baddeley stated that Æthelstan granted land for a church to the Worcester Cathedral in 929.[4] Abrams stated that there was a forged diploma for the donation of land by Æthelstan for a fishery.[7]

References

- ↑ "Parish population 2011". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ↑ Lesley Abrams (1996). Anglo-Saxon Glastonbury: Church and Endowment. Boydell & Brewer. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-85115-369-8. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ↑ Della Hooke (2010). Trees in Anglo-Saxon England: Literature, Lore and Landscape. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 169, 172. ISBN 978-1-84383-565-3. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Welbore St. Clair Baddeley (1913). Place-names of Gloucestershire; a handbook. Gloucester: J. Bellows. pp. 9–12.

- ↑ Margaret Gelling (1997). Signposts to the Past. History Press Limited. p. 35. ISBN 1-86077-376-1.

- 1 2 Charles S. Taylor; Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society (1889). An analysis of the Domesday survey of Gloucestershire. C. T. Jeffries. p. 199. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 Lesley Abrams (1996). Anglo-Saxon Glastonbury: Church and Endowment. Boydell & Brewer. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-85115-369-8. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- 1 2 I.J. Sanders (1960). "North Cadbury". English Baronies, A Study of their Origin and Descent, 1086–1327. Oxford. p. 68.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ James Baker (1901). "Aust & Wyclif". Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeology Society (BGAS). pp. 269–270.

- ↑ James Baker (1901). "Aust & Wyclif". Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeology Society (BGAS). p. 270.

- 1 2 3 David Verey; Alan Brooks (January 2002). The Buildings of England: Gloucestershire. Yale University Press. pp. 100, 158–159. ISBN 978-0-300-09733-7. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- 1 2 John Horace Round (1901). Studies in peerage and family history. A. Constable and company, ltd. pp. 194–198. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ↑ John Horace Round (1901). Studies in peerage and family history. A. Constable and company, ltd. pp. 189–194. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ↑ Thomas Dudley Fosbroke (1807). Abstracts of Records and Manuscripts Respecting the County of Gloucester: Formed Into a History, Correcting the Very Erroneous Accounts, and Supplying Numerous Deficiencies in Sir Rob. Atkins, and Subsequent Writers. J. Harris. p. 78. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- 1 2 Thomas Dudley Fosbroke (1807). Abstracts of Records and Manuscripts Respecting the County of Gloucester: Formed Into a History, Correcting the Very Erroneous Accounts, and Supplying Numerous Deficiencies in Sir Rob. Atkins, and Subsequent Writers. J. Harris. pp. 78–79. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ↑ Thomas Rudge (1803). The History of the County of Gloucester: Compressed and Brought Down to the Year 1803. Harris. p. 356. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- ↑ Severn View Services at MotorwayServices.info. Retrieved 14 July 2013

- ↑ "What happened to Richey Edwards? 20 years after Bristol sightings Manic Street Preacher's disappearance remains mystery". Bristol Post. 27 January 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ↑ "Construction cost". M48 Severn Bridge – Closures to Install Cable Drying. Archived from the original on 6 March 2008. Retrieved 12 May 2008.

- ↑ "Severn Bridge: Iconic Dylan pictures rediscovered". BBC. 8 September 2006. Retrieved 13 July 2013.