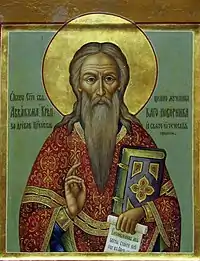

Avvakum Petrov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Great Martyr | |

| Born | 20 November 1620/21 Grigorovo, Nizhny Novgorod |

| Died | 14 April 1682 (aged 60 or 61) Pustozyorsk |

| Venerated in | Old Believers (Russian Orthodox Old-Rite Church) |

| Major shrine | Pustozyorsk, Russia |

| Feast | Repose: 14 April |

| Attributes | Dressed in a priest's robes, holding the two-fingered sign of the cross |

| Patronage | Russia |

Avvakum Petrov (Russian: Аввакум Петров; 20 November 1620/21 – 14 April 1682) (also spelled Awakum) was an Old Believer and Russian protopope of the Kazan Cathedral on Red Square who led the opposition to Patriarch Nikon's reforms of the Russian Orthodox Church. His autobiography and letters to the tsar and other Old Believers such as Boyarynya Morozova are considered masterpieces of 17th-century Russian literature.

Life and writings

He was born in Grigorovo, in present-day Nizhny Novgorod. Starting in 1652 Nikon, as Patriarch of the Russian Church, initiated a wide range of reforms in Russian liturgy and theology. These reforms were intended mostly to bring the Russian Church into line with the other Eastern Orthodox Churches of Eastern Europe and the Middle East.

Avvakum and others strongly rejected these changes. They saw them as a corruption of the Russian Church, which they considered to be the true Church of God. The other Churches were more closely related to Constantinople in their liturgies. Avvakum argued that Constantinople fell to the Turks because of these heretical beliefs and practices.

For his opposition to the reforms, Avvakum was repeatedly imprisoned. First, he was exiled to Siberia, to the city of Tobolsk, and partook in an exploration expedition under Afanasii Pashkov to the Chinese border. In 1664, after Nikon was no longer patriarch he was allowed to return to Moscow, then exiled again to Mezen, then allowed to return to Moscow again for the Church Council of 1666–67, but due to continued opposition to the reforms, he was exiled to Pustozyorsk, above the Arctic Circle, in 1667.[1] For the last fourteen years of his life, he was imprisoned there in a pit or dugout (a sunken, log-framed hut). He and his accomplices were finally executed by being burned in a log house.[2] The spot where he was burned has been commemorated by an ornate wooden cross.

Avvakum's autobiography recounts hardships of his imprisonment and exile to the Russian Far East, the story of his friendship and fallout with the Tsar Alexis, his practice of exorcising demons and devils, and his boundless admiration for nature and other works of God. Numerous manuscript copies of the text circulated for nearly two centuries before it was first printed in 1861.[3]

Legacy

Despite his persecution and death, groups rejecting the liturgical changes persisted. They came to be referred to as Old Believers.

English translations

- The Life Written by Himself, Columbia University Press, 2021 (The Russian Library). Translated by Kenneth N. Brostrom.

References

- ↑ Holl, Bruce T. (March 23, 1993). "Avvakum and the Genesis of Siberian Literature". In Slezkine, Yuri; Diment, Galya (eds.). Between Heaven and Hell: the Myth of Siberia in Russian Culture. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-349-60553-8.

- ↑ Из пыточной истории России: Сожжения заживо

- ↑ Малышев В.И., История первого издания Жития протопопа Аввакума. – «Рус лит.», 1962, № 2, с. 147

4) P. Hunt, Russia’s 17th century Crisis of Modernization: The Autobiographical Saint’s Life of the Archpriest Avvakum, The Seventeenth Century, 38:1, 155-171. A Review Article of Kenneth Brostrom’s Translation of the “Life.”

5) P. Hunt, The Theology in Avvakum’s “Life” and His Polemic with the Nikonians, The New Muscovite Cultural History, eds. M. Flier, V. Kivelson, N. S. Kollman, K. Petrone (Bloomington, In: Slavica, 2009), 125-140.

6) P. Hunt, The Holy Foolishness in the “Life” of the Archpriest Avvakum and the Problem of Innovation, Russian History, ed. L. Langer, P. Brown, 35:3-4 (2008), 275-309.

7)Priscilla Hunt, Avvakum’s “Fifth Petition” to the Tsar and the Ritual Process, Slavic and East European Journal, 46.3 (2003), 483-510

External links

- Life of Avvakum, academic edition with commentary (in Russian)

- Avvakum's letters to the Tzar and Old Believers (pub. Paris, 1951, in Russian)

- Parallel text version of Life of Avvakum Archived 9 November 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- English and Russian Articles on Avvakum by P. Hunt