| Part of a series on |

| Kabbalah |

|---|

|

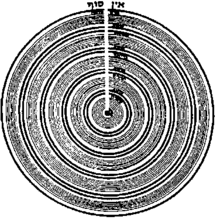

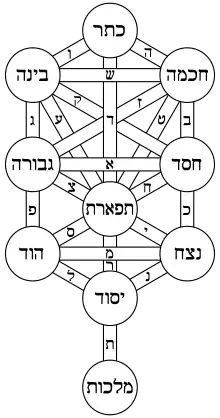

Ayin (Hebrew: אַיִן, lit. 'nothingness', related to אֵין ʾên, lit. 'not') is an important concept in Kabbalah and Hasidic philosophy. It is contrasted with the term Yesh (Hebrew: יֵשׁ, lit. 'there is/are' or 'exist(s)'). According to kabbalistic teachings, before the universe was created there was only Ayin, and the first manifest Sephirah (Divine emanation), Chochmah (Wisdom), "comes into being out of Ayin."[1] In this context, the sephirah Keter, the Divine will, is the intermediary between the Divine Infinity (Ein Sof) and Chochmah. Because Keter is a supreme revelation of the Ohr Ein Sof (Infinite Light), transcending the manifest sephirot, it is sometimes excluded from them.

Ayin is closely associated with the Ein Sof (Hebrew: אין סוף, lit. 'without end'), which is understood as the Deity prior to His self-manifestation in the creation of the spiritual and physical realms, single Infinite unity beyond any description or limitation. From the perspective of the emanated created realms, Creation takes place "Yesh me-Ayin" ("Something from Nothing"). From the Divine perspective, Creation takes place "Ayin me-Yesh" ("Nothing from Something"), as only God has absolute existence; Creation is dependent on the continuous flow of Divine lifeforce, without which it would revert to nothingness. Since the 13th century, Ayin has been one of the most important words used in kabbalistic texts. The symbolism associated with the word Ayin was greatly emphasized by Moses de León (c. 1250 – 1305), a Spanish rabbi and kabbalist, through the Zohar, the foundational work of Kabbalah.[2] In Hasidism Ayin relates to the internal psychological experience of Deveikut ("cleaving" to God amidst physicality), and the contemplative perception of paradoxical Yesh-Ayin Divine Panentheism, "There is no place empty of Him".[3]

History of Ayin-Yesh

In his Judeo-Arabic work The Book of Beliefs and Opinions (Arabic: كتاب الأمانات والاعتقادات, romanized: Kitāb al-Amānāt wa l-Iʿtiqādāt, Hebrew: אמונות ודעות, romanized: Emunoth ve-Deoth), Saadia Gaon, a prominent 9th-century rabbi and the first great Jewish philosopher, argues that "the world came into existence out of nothingness". This thesis was first translated into Hebrew as "yesh me-Ayin", meaning "something from nothing", in the 11th century.[4]

Jewish philosophers of the 9th and 10th century adopted the concept of "yesh me-Ayin", contradicting Greek philosophers and Aristotelian view that the world was created out of primordial matter and/or was eternal.[2]

Both Maimonides and the centuries earlier author of the kabbalistic related work Sefer Yetzirah "accepted the formulation of Creation, "yesh me-Ayin.""[4] Chapter 2, Mishnah 6 of the latter includes the sentence: "He made His Ayin, Yesh". This statement, like most in Jewish religious texts, can be interpreted in different ways: for example, "He made that which wasn't into that which is", or "He turned His nothingness into something." Joseph ben Shalom Ashkenazi, who wrote a commentary on Sefer Yetzirah in the 14th century, and Azriel of Gerona, Azriel ben Menahem, one of the most important kabbalists in the Catalan town of Girona (north of Barcelona) during the 13th century, interpreted the Mishnah's "He made His Ayin, Yesh" as "creation of "yesh me-Ayin.""[4]

Maimonides and other Jewish philosophers argued a doctrine of "negative theology", which says there are no words to describe what God is, and we can only describe what "God is not". Kabbalah accepted this in relation to Ayin, becoming one of the philosophical concepts underlying its significance.[4] However, Kabbalah involves itself with the different, more radical proposition that God becomes known through His emanations of Sephirot, and spiritual Realms, Emanator ("Ma'ohr") and emanations ("Ohr") comprising the two aspects of Divinity.

For kabbalists, Ayin became the word to describe the most ancient stage of creation and was therefore somewhat paradoxical, as it was not completely compatible with "creation from nothing". Ayin became for kabbalists a symbol of "supreme existence" and "the mystical secret of being and non-being became united in the profound and powerful symbol of the Ayin".[2] There is also a paradoxical relationship between the meaning of Ayin and Yesh from kabbalistic point of view. Rachel Elior, professor of Jewish philosophy and mysticism at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, writes that for kabbalists Ayin (nothingness) "clothes itself" in Yesh (everything there is) as "concealed Torah clothes itself in revealed Torah".[5]

Kabbalists on Ayin-Yesh

David ben Abraham ha-Laban, a 14th-century kabbalist, says:

Nothingness (ayin) is more existent than all the being of the world. But since it is simple, and all simple things are complex compared with its simplicity, it is called ayin.[6]

Z'ev ben Shimon Halevi says:

AYIN means No-Thing. AYIN is beyond Existence, separate from any-thing. AYIN is Absolute Nothing. AYIN is not above or below. Neither is AYIN still or in motion. There is nowhere where AYIN is, for AYIN is not. AYIN is soundless, but neither is it silence. Nor is AYIN a void – and yet out of the zero of AYIN'S no-thingness comes the one of EIN SOF[7]

Ayin-Yesh in Hasidism

Hasidic master Dov Ber of Mezeritch says:

one should think of one's self as Ayin, and that "absolute all" and "absolute nothingness" are the same, and that the person who learns to think about himself as Ayin will ascend to a spiritual world, where everything is the same and everything is equal: "life and death, ocean and dry land."[1][7]

This reflects the orientation of Hasidism to internalise Kabbalistic descriptions to their psychological correspondence in man, making Deveikut (cleaving to God) central to Judaism. The populist aspect of Hasidism revived common folk through the nearness of God, especially reflected in Hasidic storytelling and the public activity of the Baal Shem Tov, Hasidism's founder. Dov Ber, uncompromising esoteric mystic and organiser of the movement's future leaders, developed the elite aspect of Hasidic meditation reflected in Bittul (annihilation of ego) in the Divine Ayin Nothingness.

Schneur Zalman of Liadi, one of Dov Ber's inner circle of followers, developed Hasidic thought into an intellectual philosophical system that related the Kabbalistic scheme to its interpretation in the Hasidic doctrine of Panentheism. The Chabad follower contemplates the Hasidic interpretation of Kabbalistic structures, including the concept of Ayin, during prolonged prayer. Where Kabbalah is concerned with categorising the Heavenly realms using anthropomorphic terminology, these texts of Hasidic philosophy seek to perceive the Divinity within the structures, by relating to their correspondence in man using analogies from man's experience. Rachel Elior termed her academic study of Habad intellectual contemplation "the Paradoxical ascent to God", as it describes the dialectical paradox of Yesh-Ayin of Creation. In the second section of his magnum opus Tanya, Schneur Zalman explains the Monistic illusionary Ayin nullification of Created Existence from the Divine perspective of "Upper Unity". The human perspective in contemplation sees Creation as real Yesh existence, though completely nullified to its continuous vitalising Divine lifeforce, the perception of "Lower Unity". In another text of Schneur Zalman:

He is one in the heaven and on earth... because all the upper worlds occupy no space to be Yesh and something separate in itself, and everything before Him is as Ayin, verily as null and void, and there is nothing beside Him. (Torah Or Mi-Ketz p.64)[8]

Here, the Lower Unity perspective is ultimately false, arising out of illusionary concealment of Divinity. In Schneur Zalman's explanation, Hasidism interprets the Lurianic doctrine of Tzimtzum (apparent "Withdrawal" of God to allow Creation to take place) as only an illusionary concealment of the Ohr Ein Sof. In truth, the Ein Sof and the Ohr Ein Sof still fills all Creation, without any change at all from God's perspective.

Atzmus-Essence resolving the Ayin-Yesh paradox of Creation

_-_TIMEA.jpg.webp)

In Chabad systemisation of Hasidic thought, the term Ein Sof ("Unlimited" Infinite) itself does not capture the very essence of God. Instead it uses the term Atzmus (the Divine "Essence"). The Ein Sof, while beyond all differentiation or limitation, is restricted to Infinite expression. The true Divine essence is above even Infinite-Finite relationship. God's essence can be equally manifest in finitude as in infinitude, as found in the Talmudic statement that the Ark of the Covenant in the First Temple took up no space. While it measured its own normal width and length, the measurements from each side to the walls of the Holy of Holies together totalled the full width and length of the sanctuary. Atzmus represents the core Divine essence itself, as it relates to the ultimate purpose of Creation in Hasidic thought that "God desired a dwelling place in the lower Realms",[9] which will be fulfilled in this physical, finite, lowest world, through performance of the Jewish observances.

This gives the Hasidic explanation why Nachmanides and the Kabbalists ruled that the final eschatological era will be in this World, against Maimonides's view that it will be in Heaven, in accordance with his philosophical view of the elevation of intellect over materiality in relating to God. In Kabbalah, the superiority of this world is to enable the revelation of the complete Divine emanations, for the benefit of Creation, as God Himself lacks no perfection. For example, the ultimate expression of the sephirah of Kindness (Chesed) is most fully revealed when it relates to our lowest, physical World. However, the Hasidic interpretation sees the Kabbalistic explanations as not the ultimate reason, as, like Kabbalah in general, it relates to the Heavenly realms, which are not the ultimate purpose of Creation. The revelation of Divinity in the Heavenly realms is supreme, and superior to the present concealment of God in this World. However, it is still only a limited manifestation of Divinity, the revelation of the Sefirot attributes of God's Wisdom, Understanding, Kindness, Might, Harmony, Glory and so forth, while God's Infinite Ein Sof and Ohr Ein Sof transcend all Worlds beyond reach. In contrast, the physical performance of the Mitzvot in this world, instead relate to, and ultimately will reveal, the Divine essence.

In Hasidic terminology, the separate realms of physicality and spirituality are united through their higher source in the Divine essence. In the Biblical account, God descended on Mount Sinai to speak to the Israelites "Anochi Hashem Elokecha" ("I am God your Lord").[10] This is explained in Hasidic thought to describe Atzmus, the Divine essence (Anochi-"I"), uniting the separate Kabbalistic manifestation realms of spirituality (Hashem-The Tetragrammaton name of Infinite transcendent emanation) and physicality (Elokecha-The name of God relating to finite immanent lifeforce of Creation). Before the Torah was given, physical objects could not become sanctified. The commandments of Jewish observance, stemmining from the ultimate Divine purpose of Creation in Atzmus, enabled physical objects to be used for spiritual purposes, uniting the two realms and embodying Atzmus. In this ultimate theology, through Jewish observance, man converts the illusionary Ayin-nothingness "Upper Unity" nullification of Creation into revealing its ultimate expression as the ultimate true Divine Yesh-existence of Atzmus. Indeed, this gives the inner reason in Hasidic thought why this world falsely perceives itself to exist, independent of Divinity, due to the concealment of the vitalising Divine lifeforce in this world. As this world is the ultimate purpose and realm of Atzmus, the true Divine Yesh-existence, so externally it perceives its own Created material Yesh-existence ego.

In Chabad systemisation of Hasidic philosophy, God's Atzmut-essence relates to the 5th Yechidah Kabbalistic Etzem-essence level of the soul, the innermost Etzem-essence root of the Divine Will in Keter, and the 5th Yechidah Etzem-essence level of the Torah, the soul of the 4 Pardes levels of Torah interpretation, expressed in the essence of Hasidic thought.[11] In the Sephirot, Keter, the transcendent Divine Will, becomes revealed and actualised in Creation through the first manifest Sephirah Chochmah-Wisdom. Similarly, the essential Hasidic purpose-Will of Creation, a "dwelling place for God's Atzmus-essence in the lowest world", becomes actualised through the process of elevating the sparks of holiness embedded in material objects, through using them for Jewish observances, the Lurianic scheme in Kabbalah-Wisdom. Once all the fallen sparks of holiness are redeemed, the Messianic Era begins. In Hasidic explanation, through completing this esoteric Kabbalah-Wisdom process, thereby the more sublime ultimate Divine purpose-Will is achieved, revealing this World to be the Atzmus "dwelling place" of God. In Kabbalah, the Torah is the Divine blueprint of Creation: "God looked into the Torah and created the World".[12] The Sephirah Keter is the Supreme Will underlying this blueprint, the source of origin of the Torah. According to Hasidic thought, "the Torah derives from Chochmah-Wisdom, but its source and root surpasses exceedingly the level of Chochmah, and is called the Supreme Will".[13] This means that according to Hasidic thought, Torah is an expression of Divine Reason. Reason is focused towards achieving a certain goal. However, the very purpose of achieving that goal transcends and permeates the rational faculty. Once reason achieves the goal, the higher innermost essential will's delight is fulfilled, the revelation of Atzmus in this World. Accordingly, Hasidic thought says that then this World will give life to the spiritual Worlds, and the human body will give life to the soul. The Yesh of ego will be nullified in the Divine Ayin, becoming the reflection of the true Divine Yesh.

Atzmus in the eschatological future

The resolution of the Ayin-Yesh paradox of Creation through Atzmus is beyond present understanding, as it unites the Finite-Infinite paradox of Divinity. This is represented in the paradox of the Lurianic Tzimtzum, interpreted non-literally in Hasidic Panentheism. God remains within the apparent "vacated" space of Creation, just as before, as "I the Eternal, I have not changed" (Malachi 3:6), the Infinite "Upper Unity" that nullifies Creation into Ayin-nothingness. Creation, while dependent on continual creative lifeforce, perceives its own Yesh-existence, the Finite "Lower Unity". The absolute unity of Atzmus, the ultimate expression of Judaism's Monotheism, unites the two opposites. Maimonides codifies the Messianic Era and the physical Resurrection of the Dead as the traditionally accepted last two Jewish principles of faith, with Kabbalah ruling the Resurrection to be the final, permanent eschatology. Presently, the supernal Heavenly realms perceive the immanent Divine creative Light of Mimalei Kol Olamim ("Filling all Worlds"), according to their innumerably varied descending levels. In the Messianic Era, this world will perceive the transcendent Light of Sovev Kol Olamim ("Encompassing all Worlds"). In the Era of the Resurrection, generated through preceding Jewish observance "from below", the true presence of Atzmus will be revealed in finite physical Creation. A foretaste of this was temporarily experienced at Mount Sinai, when the whole Nation of Israel heard the Divine pronouncement, while remaining in physicality. As this was imposed "from above" by God, the Midrash says that God revived their souls from expiring with the future "Dew of the Resurrection".

The concept of Ayin-Yesh in literature and science

In his autobiographical trilogy Love and Exile, Isaac Bashevis Singer, an American-Jewish writer and a Nobel Prize laureate, remembers how he studied Kabbalah and tried to comprehend how could have it been that he,

Rothschild, the mouse in its hole, the bedbug on the wall, and the corpse in the grave were identical in every sense, as were dream and reality...[14]

Scientific theories of the Big Bang and ideas about the Universe being created out of nothingness resembles those expressed in Kabbalah. "One reads Stephen Hawking's A Brief History of Time, perhaps a sign of things to come, and the affinities with Kabbalah are striking."[15] Kenneth Hanson sees similarity in the Kabbalistic idea that Hebrew letters were the material of which the Universe was built and Stephen Hawking's explanation why Albert Einstein's Theory of relativity will break down at some point that he called the "singularity". Hanson says that although Hebrew letters have shapes they are actually made out of nothing, as well as the singularity of the Big Bang. Hanson also argues that the singularity of black holes could be compared to Kabbalistic "spheres of nothing", as it was written in the Sefer Yetzirah: "For that which is light is not-darkness, and that which is darkness is not-light."[16]

In their book The Grand Design physicists Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow argue that there was nothing before the Beginning, and explain it by comparing the Beginning to South Pole. They say: "there is nothing south of the South Pole", and there was nothing before the Beginning.[17]

See also

- Jewish philosophy

- Kabbalah

- Hasidic thought

References

- 1 2 Daniel Chanan Matt (May 10, 1996). The Essential Kabbalah: The Heart of Jewish mysticism. HarperOne. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0-06-251163-8. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 Joseph Dan (1987). Argumentum e Silentio. W. de Gruyter. pp. 359–362. ISBN 978-0-89925-314-5. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ↑ Tikkunei Zohar 57, made into the central doctrine of Hasidic Divine immanence

- 1 2 3 4 Mark Elber (March 31, 2006). The Everything Kabbalah Book: Explore This Mystical Tradition--From Ancient Rituals to Modern Day Practices (Everything: Philosophy and Spirituality). Adams Media Corporation. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-59337-546-1. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ↑ Rachel Elior. "The infinity of meaning embedded in the sacred text" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-21. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ↑ Josef Blaha (2010). Lessons from the Kabbalah and Jewish history. Marek Konecný. p. 15. ISBN 9788090386051. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- 1 2 Z'ev ben Shimon Halevi (June 1977). A Kabbalistic Universe. Weiser Books; Trade Paperback Edition. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-87728-349-2. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ↑ Rachel Elior (November 1992). The paradoxical ascent to God: the kabbalistic theosophy of Habad Hasidism. State University of New York Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-7914-1045-5. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ↑ Schneur Zalman of Liadi: Tanya I:36, further explained in later Chabad thought (see Atzmut), defines this as the ultimate reason for Creation, taking the statement from Rabbinic Midrash Tanhuma: Nasso 16

- ↑ Exodus 20:2. In this verse the names of God are translated opposite to their usual form ("I am the Lord thy God"), as in Kabbalah the Tetragrammaton describes Divine Infinitude ("God", the Ein Sof power of Creation through the Sephirah Keter-Supreme Will, combining the words "was","is" and "will be" in one name), while Elokim describes God's concealing limitation to allow His lifeforce to immanently form the finite Worlds (becoming "Lord", the master relating to this world through the last sephirah Malkuth-Kingship, numerically equivalent to "HaTevah"-"Nature")

- ↑ On the Essence of Chasidus by Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, Kehot publications Bilingual Hebrew-English edition

- ↑ Genesis Rabbah I:1, ZoharI:5a

- ↑ Tanya IV:1

- ↑ Isaac Bashevis Singer (May 1, 1996). Love and Exile: An Autobiographical Trilogy. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-374-51992-6. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ↑ Robert M. Seltzer and Norman J. Cohen (February 1, 1995). The Americanization of the Jews. NYU Press. p. 455. ISBN 978-0-8147-8001-5. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ↑ Kenneth Hanson (April 1, 2004). Kabbalah: The Untold Story of the Mystic Tradition. Council Oak Books. p. 230. ISBN 978-1-57178-142-0. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ↑ Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow (September 7, 2010). The Grand Design. Bantam. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-553-80537-6. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

Further reading

- Ayin: The Concept of Nothingness in Jewish Mysticism, Daniel C. Matt, in Essential Papers on Kabbalah, ed. by Lawrence Fine, NYU Press 2000, ISBN 0-8147-2629-1

- The Paradigms of Yesh and Ayin in Hasidic Thought, Rachel Elior, in Hasidism Reappraised, ed. by Ada Rapoport-Albert, Littman Library 1997, ISBN 1-874774-35-8