| Baška tablet | |

|---|---|

| Bašćanska ploča | |

| |

| Material | Limestone |

| Long | 199 cm (78 in) |

| Height | 99.5 cm (39.2 in) |

| Weight | c. 800 kg (1,800 lb) |

| Created | late 11th-early 12th century (c. 1100[1]) |

| Discovered | 1851 Church of St. Lucy, Jurandvor near Baška, Krk |

| Discovered by | Petar Dorčić |

| Present location | Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Zagreb |

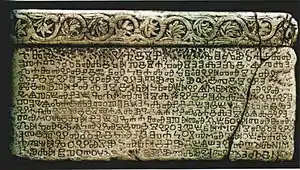

Baška tablet (Croatian: Bašćanska ploča, pronounced [bâʃt͡ɕanskaː plɔ̂t͡ʃa]) is one of the first monuments containing an inscription in the Croatian recension of the Church Slavonic language, dating from c. 1100 AD. On it Croatian ethnonym and king Demetrius Zvonimir are mentioned for the first time in native Croatian language. The inscription is written in the Glagolitic script. It was discovered in 1851 at Church of St. Lucy in Jurandvor near the village of Baška on the Croatian island of Krk.

History

The tablet was discovered on 15 September 1851 by Petar Dorčić during paving of the Church of St. Lucy in Jurandvor near the village of Baška on the island of Krk.[2] Already then a small part of it was broken.[2]

Since 1934, the original tablet has been kept at the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Zagreb.[1] Croatian archaeologist Branko Fučić contributed to the interpretation of Baška tablet as a left altar partition. His reconstruction of the text of the Baška tablet is the most widely accepted version today.[3]

Description

The Baška tablet is made of white limestone. It is 199 cm wide, 99.5 cm high, and 7.5–9 cm thick. It weighs approximately 800 kilograms.[1][4] The tablet was installed as a partition between the altar and the rest of the church, specifically, it was left pluteus of the cancellus/septum (the right pluteus tablet is so-called "Jurandvorski ulomci/Jurandvor fragments" with four preserved pieces which were also found on the pavement, mentions name of Zvonimir, Croatia, Lucia, word "opat", "prosih" and "križ", has almost the same but smaller letters and it is also dated to the 11th and 12th century[5]).[2] According to historical sources the cancellus was preserved at least until 1752, when somewhere since then until before 1851 was destroyed and the tablet placed on the pavement of the church.[2] A replica is in place in the church.[2]

The inscribed stone slab records King Zvonimir's donation of a piece of land to a Benedictine abbey in the time of abbot Držiha. The second half of the inscription tells how abbot Dobrovit built the church along with nine monks.[1] The inscription is written in the Glagolitic script, exhibiting features of Church Slavonic of Croatian recension influenced by Chakavian dialect of Croatian language, such as writing (j)u for (j)ǫ, e for ę, i for y, and using one jer only (ъ). It also has several Latin and Cyrillic letters (i, m, n, o, t, v) which combination was still common for that period. It provides the only example of transition from Glagolitic of the rounded Bulgarian (old Slovak) type to the angular Croatian alphabet type.[1][2]

Contents

The scholars who took part in deciphering of the Glagolitic text dealt with palaeographic challenges, as well as the problem of the damaged, worn-out surface of the slab. Through successive efforts, the contents were mostly interpreted before World War I, but remained a topic of study throughout the 20th century.[6][2]

One of the most disputed parts of it is the mention of "Mikula/Nicholas in Otočac", considered as a reference, or to the church and later monastery of St. Mikula/Nicholas in Otočac in Northwestern part of Lika (but earliest historical mention dating to the 15th century), or to the toponym of St. Lucia's estate of Mikulja in Punat on Krk which is an island (in Croatian island is "otok" with "Otočac" being a derivation), or somewhere else on Krk and its surroundings (like monastery of St. Nicholas near Omišalj, old churches of St. Nicholas in Bosar, Ogrul, Negrit or island of Susak).[2] Lately, church historian Mile Bogović supported the thesis about St. Nicholas in Otočac because the Gregorian Reform during Zvonimir's reign went from Croatian inland toward recently conquered Byzantine lands (Krk was one of the Dalmatian city-states part of the theme of Dalmatia), and linguist Valentin Putanec based on the definition of krajina in the dictionary by Bartol Kašić and Giacomo Micaglia (meaning coastline and inland of Liburnia) argued it shows connection between Benedictines in Krk and Otočac in Lika.[7]

The original text, with unreadable segments marked gray:

ⰰⰸⱏ–––––ⱌⰰⱄⰻⱀⰰ––ⱅⰰⰳⱁⰴⱆⱈⰰⰰⰸⱏ

ⱁⱂⰰⱅ–ⰴⱃⱏⰶⰻⱈⱝⱂⰻⱄⰰⱈⱏⱄⰵⱁⰾⰵⰴⰻⱑⱓⰶⰵ

ⰴⰰⰸⱏⰲⱏⱀⰻⰿⱃⱏⰽⱃⰰⰾⱏⱈⱃⱏⰲⱝⱅⱏⱄⰽⱏ–––

ⰴⱀⰻⱄⰲⱁⱗⰲⱏⱄⰲⰵⱅⱆⱓⰾⱆⱌⰻⱓⰻⱄⰲⰵ––

ⰿⰻⰶⱆⱂⱝⱀⱏⰴⰵⱄⰻ–ⱃⱝⰽⱃⱏⰱⱝⰲⱑⰿⱃⱝ–––ⱏⰲⱏ––

ⱌⱑⱂⱃⰱⱏⱀⰵⰱⰳⰰ–ⱏⱂⱁⱄⰾ–ⰲⰻⱀⱁⰴⰾⱑ––ⰲⰰⰲⱁ

ⱅⱁⱌⱑⰴⰰⰻⰶⰵⱅⱉⱂⱁⱃⱒⰵⰽⰾⱏⱀⰻⰻⰱⱁⰻⰱ–ⰰⱂⰾⰰⰻⰳⰵ

ⰲⰰⰼⰾⰻⱄⱅ҃ⰻⰻⱄⱅ҃ⰰⱑⰾⱆⱌⰻⱑⰰⱞⱀⱏⰴⰰⰻⰾⰵⱄⰴⱑⰶⰻⰲⰵ

ⱅⱏⱞⱉⰾⰻⰸⱝⱀⰵⰱ҃ⱁⰳⰰⰰⰸⱏⱁⱂⱝⱅⱏⰴⰱⱃⱉⰲⱜⱅⱏⰸⱏ

ⰴⱝⱈⱏⱌⱃ꙯ⱑⰽⱏⰲⱏⱄⰻⱅⰻⱄⰲⱉⰵⱓⰱⱃⱝⰰⱜⱓⱄⱏⰴⰵⰲ

ⰵⱅⰻⱓⰲⱏⰴⱀⰻⰽⱏⱀⰵⰸⰰⰽⱉⱄⱏⱞⱏⱅⱝⱉⰱⰾⰰⰴ

ⰰⱓⱋⱝⰳⱉⰲⱏⱄⱆⰽⱏⱃⱝⰻⱀⱆⰻⰱⱑⱎⰵⰲⱏⱅⱏⰾNⱜⱞ

ⱜⰽⱆⰾⱝⰲⱏⱉтⱉⱒⱍ–––ⰲⰵт꙯ⱆⱓⰾⱆⱌ꙯ⱜⱓⰲⱏⰵⰴⰻNⱉ

The transliterated text, according to Branko Fučić (1960s, last update 1982-1985),[8][2] with restored segments in square brackets, is as follows:

| Original text transliterated to Latin | The same text in modern Croatian | The same text in English |

|---|---|---|

|

a[zъ vъ ime o]tca i s(i)na [i s](ve)tago duha azъ opat[ъ] držiha pisahъ se o ledi[n]ě juže da zъvъnimirъ kralъ hrъvatъskъï [vъ] dni svoję vъ svetuju luciju i sv[edo]- mi županъ desim(i)ra krъ[ba]vě mra[tin]ъ vъ l(i)- cě pr(i)bъnebža [s]ъ posl[ъ] vin[od](o)lě [ěk](o)vъ v(ъ) o- tocě da iže to poreče klъni i bo(g) i bï(=12) ap(osto)la i g(=4) e- van(je)listi i s(ve)taě luciě am(e)nъ da iže sdě žive- tъ moli za ne boga azъ opatъ d(o)brovitъ zъ- dah crěkъvъ siju i svoeju bratiju sъ dev- etiju vъdni kъneza kosъmъta oblad- ajućago vъsu kъrainu i běše vъ tъ dni m- ikula vъ točъci [sъ s]vetuju luciju vъ edino |

Ja, u ime Oca i Sina i Svetoga Duha. Ja opat Držiha pisah ovo/to o ledini koju dade Zvonimir, kralj hrvatski, u svoje dane svetoj Luciji, i svjedoci župan Desimir u Krbavi, Martin u Lici, Piribineg posal u Vinodolu i Jakov na otoku. Da tko to poreče, prokleo ga Bog i 12 apostola i 4 evanđelista i sveta Lucija. Amen. Da tko ovdje živi, moli za njih Boga. Ja opat Dobrovit zidah crkvu ovu sa svoje devetero braće u dane kneza Kosmata koji je vladao cijelom Krajinom. I bješe u te dane Mikula u Otočcu sa svetom Lucijom zajedno |

I, in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit. I abbot Držiha wrote this about the land which gave Zvonimir, the Croatian king, in his days to St. Lucia, and witnesses župan Desimir in Krbava, Martin in Lika, Piribineg deputy in Vinodol and Jakov on island. Whoever denies this, be cursed by God and the twelve apostles and the four evangelists and Saint Lucia. Amen. May he who lives here, pray for them to God. I abbot Dobrovit built this church with nine of my brethren in the days of knez/count Cosmas who ruled over the entire Krajina. And in those days Nicholas in Otočac was one with St. Lucia |

Dating

Several evidences show that the tablet is dated to the late 11th or early 12th century (c. 1100 CE).[1][2] The tablet's content suggests it was inscribed after the death of King Zvonimir (who died in 1089), since abbot Držiha describes Zvonimir's donation as an event that happened further in the past ("in his days").[1] The Church of St. Lucy, described as having been built during the reign of count Kosmat (possibly identified with župan of Luka in 1070 or comes Kuzma who was in the entourage of Coloman, King of Hungary to Zadar in 1102[9][10]) who ruled over whole Krajina (probably a reference to a local place on island of Krk or March of Dalmatia from the 1060s which was composed of part of Kvarner and the eastern coast of Istria[9][10]), suggests the period of Croatian succession crisis of the 1090s and before the Venetian domination since 1116 and first mention of counts of Krk in 1118-1130 (later known as Frankopan family).[1][2] Lujo Margetić considered it was erected by the same counts of Krk between 1105-1118.[11] Desimir is identified with Desimir župan of Krbava mentioned in the 1078 charter of king Zvonimir, while Pribineg some scholars identified with Pirvaneg župan of Luka in 1059.[2] Ornamental decoration of the tablet, and early Romanesque (11-12th century) features of the church of St. Lucy similar to three other churches founded by 1100 on Krk also show it is dated at the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries.[1][2] Lately art historian Pavuša Vežić argued that the church is dated to the late Romanesque period (in the beginning of the 14th century) and Baška tablet text to 1300 with only ornamental decoration from 1100.[12][13] Although new dating of the church was accepted by scholars like Margetić, they still considered it does not change the early 12th century dating of the whole tablet which features are "hardly possible" for the middle of the 12th century and "unimaginable" for the beginning of the 14th century.[14]

Scholars argue that the textual background for the inscription was made in the period between abbot Držiha and Dobrovit, probably based on the church's cartulary.[1][2] It is considered that the fact it was inscribed at once as one unit (scriptura continua) rejects the thesis different rows were inscribed in two, three or four different periods as argued by Franjo Rački (two, 1078 and 1092-1102), Rudolf Strohal (four, between 1076 and 1120), Ferdo Šišić (two, until 1100), Vjekoslav Štefanić (three, between 1089 and 1116), Josip Hamm (three, 1077/1079, end of the 11th century and around 1100), Leo Košuta (three, similar to Hamm).[2]

The meaning of the opening lines is contested. While some scholars interpret the introductory characters simply as Azъ ("I"), others believe that letters were also used to encode the year. There is no agreement, however, on the interpretation: 1100, 1077, 1079, 1105 and 1120 have been proposed.[6][15][16]

Significance

The name of Croatia and King Zvonimir are mentioned on the tablet for the first time in Croatian.[17]

Despite the fact of not being the oldest Croatian Glagolitic monument (the Plomin tablet, Valun tablet, Krk inscription, are older and appeared in the 11th century) and in spite of the fact that it was not written in the pure Croatian vernacular - it has nevertheless been referred to by Stjepan Ivšić as "the jewel" of Croatian,[17] while Stjepan Damjanović called it "the baptismal certificate of Croatian culture".[18] It features a vaguely damaged ornamental string pattern, the Croatian interlace (Croatian: troplet).

The tablet was depicted on the obverse of the Croatian 100 kuna banknote, issued in 1993 and 2002,[19] and on a postage stamp issued by Croatian Post in 2000.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Brozović, Dalibor. "Iz povijesti hrvatskoga jezika". ihjj.hr (in Croatian). Institute of Croatian Language and Linguistics. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Bratulić, Josip (2019). "Glagoljaški lapidarij: O Bašćanskoj ploči, Tajna Bašćanske ploče". Aleja glagoljaša: stoljeća hrvatske glagoljice [Glagolitic Alley: Centuries of Croatian Glagolism] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Znamen. pp. 74–75, 79–102. ISBN 978-953-6008-58-2.

- ↑ "Fučić, Branko", Croatian Encyclopedia (in Croatian), Leksikografski zavod Miroslav Krleža, 1999–2009, retrieved January 2, 2014

- ↑ "The Baška Tablet - "The Jewel"". info.hazu.hr. Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts. 16 March 2011. Archived from the original on 18 October 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ↑ Fučić 1971, p. 242–247.

- 1 2 Fučić 1971, p. 238.

- ↑ Galović 2004, pp. 310.

- ↑ "Institut za hrvatski jezik i jezikoslovlje".

- 1 2 "Kosmat", Croatian Encyclopedia (in Croatian), Miroslav Krleža Lexicographical Institute, 2021

- 1 2 Ćosković, Pejo (2009), "Kosmat", Croatian Biographical Lexicon (HBL) (in Croatian), Miroslav Krleža Lexicographical Institute

- ↑ Margetić 2007, pp. 13.

- ↑ Galović 2004, pp. 309.

- ↑ Margetić 2007, pp. 3.

- ↑ Margetić 2007, pp. 3, 7–11:Nasuprot tomu, ne čini nam se prihvatljivom Vežićeva teza da je natpis na Ploči nastao oko 1300. godine. Scriptura continua i arhaične jezične i pismovne značajke Ploče vrlo teško dopuštaju pomicanje granice njezina klesanja čak i prema sredini 12. stoljeća, a pogotovu su nezamislive za početak 14. stoljeća. Natpis na Ploči treba iz tih razloga svakako datirati s početkom 12. stoljeća

- ↑ Galović 2018, pp. 267–268.

- ↑ Margetić 2007, pp. 11–13.

- 1 2 "Bašćanska ploča". Croatian Encyclopedia (in Croatian). Miroslav Krleža Institute of Lexicography. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ↑ Damjanović, Stjepan (7 March 2019). "Bašćanska ploča – krsni list hrvatske kulture". hkm.hr (in Croatian). Hrvatska katolička mreža. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ↑ Features of Kuna Banknotes Archived 2009-05-06 at the Wayback Machine: 100 kuna Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine (1993 issue) & 100 kuna Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine (2002 issue). – Retrieved on 30 March 2009.

Bibliography

- Fučić, Branko (September 1971). "Najstariji hrvatski glagoljski natpisi". Slovo (in Croatian). Old Church Slavonic Institute. 21: 227–254. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- Galović, Tomislav (2004). "900 godina Bašćanske ploče (1100.-2000.) – radovi sa znanstvenog skupa, ur. P. Strčić, Krčki zbornik sv. 42 – pos. izd. 36, Baška 2000., 348 str". Radovi (in Croatian). 34-35-36 (1): 307–311. Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- Galović, Tomislav (December 2018). "Milan Moguš i Bašćanska ploča". Senjski zbornik (in Croatian). 45 (1): 265–285. doi:10.31953/sz.45.1.3. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Margetić, Lujo (December 2007). "O nekim osnovnim problemima Bašćanske ploče" [About some general problems regarding the Baška tablet]. Croatica Christiana Periodica (in Croatian). Catholic Faculty of Theology, University of Zagreb. 31 (60): 1–15. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

Further reading

- "900 Years of the Baska Stone Tablet (Souvenir Sheet)". epostshop.hr. Croatian Post. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- Deželić, Mladen (1943). "Baščanska ploča i njeno konzerviranje" (PDF). Ljetopis Hrvatske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti (in Croatian). Zagreb: Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts. 54: 152–158. Retrieved 22 January 2020.