| Armour-piercing, capped, ballistic capped shell |

|---|

|

|

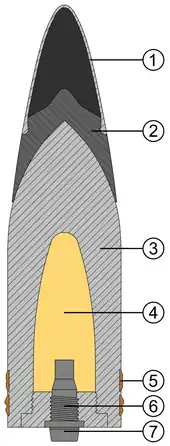

Armour-piercing, capped, ballistic capped (APCBC) is a type of configuration for armour-piercing ammunition introduced in the 1930s to improve the armour-piercing capabilities of both naval and anti-tank guns. The configuration consists of an armour-piercing shell fitted with a stubby armour-piercing cap (AP cap) for improved penetration properties against surface hardened armour, especially at high impact angles,[1] and an aerodynamic ballistic cap on top of the AP cap to correct for the poorer aerodynamics, especially higher drag, otherwise created by the stubby AP cap.[2] These features allow APCBC shells to retain higher velocities and to deliver more energy to the target on impact, especially at long range when compared to uncapped shells.

The configuration is used on both inert and explosive armour-piercing shell types:[2]

- Armour-piercing (AP), capped, ballistic capped (APCBC)

- Semi-armour-piercing (SAP), capped, ballistic capped (SAPCBC)

- Armour-piercing, high-explosive (APHE), capped, ballistic capped (APHECBC)

- Semi-armour-piercing, high-explosive (SAPHE), capped, ballistic capped (SAPHECBC)

The APCBC configuration is an evolution of the earlier APC configuration (armour-piercing, capped), itself an evolution of the simple AP configuration (armour-piercing, uncapped). The APCBC configuration is however expensive and thus a large amount of both historical and modern armour-piercing ammunition uses only one of the two caps: APC (armour-piercing, capped) and APBC (armour-piercing, ballistic capped).

Design

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

| AP | APC | APBC | APCBC |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |

Projectile body | Projectile body Armour-piercing cap | Projectile body Ballistic cap | Projectile body Armour-piercing cap Ballistic cap |

| Uncapped | Capped | Ballistic capped | Capped, ballistic capped |

Ballistic cap

By 1910 it was well-established that the aerodynamically optimal form of a solid projectile does not lend itself to best-attainable armour penetration, and remedies were devised.[3]

A ballistic cap (BC) is a hollow thin-walled aerodynamically shaped metal cone mounted on the top of a projectile to cover it with a more aerodynamically efficient shape. This reduces drag in flight, so higher velocity and hence range is obtained giving better penetration over longer distances. On impact, the ballistic cap will break off or collapse without affecting the impact performance of the armour-piercing cap and penetrator.[2]

Ballistic caps are used on a great variety of projectiles other than APCBC shells and exist to allow the projectile or cap underneath to have a less aerodynamic shape more suitable for the effect of the munition. They are most often fitted by pressing the edges of the cone into a groove around the edge of the projectile or AP cap.[2]

Armour-piercing cap

The primary job of an armour-piercing cap (AP cap, most often shortened to cap) is to protect the tip of the penetrator (the shell) on impact, which could otherwise shatter and not penetrate.[2] It consist of a metal cap, often solid in structure, which, is mounted on top of the projectile lying against the tip. Depending on the purpose of the cap, different designs exist. Among other things, the cap can be made of soft metal (soft cap), or hard metal (hard cap).[2]

- Soft caps were the original design in use. Unlike hard caps, soft caps primarily only help with protecting the penetrator on impact.[1] They spread the radial shock outward from the impact along the radius of the now flattened soft cap, keeping the shock from travelling into the body of the shell itself.[1] Soft caps, however, do not function at high impact angles. At angles of impact (obliquities) of 15° or greater, they start to be torn free prior to functioning, and do not fully function over 20°.[1] Following World War I, soft caps started being discarded for naval shells. One reason was their inability to function at high impact angles, but also because of improved metallurgy following the war which had led to face-hardened armour of a tougher grade than before that negated the soft cap.[1] On impacting tough face-hardened armour the soft cap will protect the penetrator in the initial impact, but once the penetrator has passed through the soft cap, the hardened armour surface, backed up by the soft depth plate, will not cave in and the penetrator is destroyed by the crushing forces surrounding it.[1]

- Hard caps were introduced after soft caps fell out of favour. Unlike soft caps, hard caps not only helps with protecting the penetrator on impact, but most often also helps guide the projectile into armour at high impact angles.[1] This is achieved by giving the hard cap a blunt shaped tip, often with sharp edges, which allows it to grip into armour even at high impact angles.[2] Unlike soft caps, hard caps functions against face-hardened armour and even counters it. It does this, much like drilling a hole in wood before one uses a screw, by punching through the hardened surface of face-hardened armour, destroying itself in the process. The penetrator then passed through the hole in the hardened surface and enters the soft back of the armour, going through it or creating spalling on the other side.[1]

History

Early World War II-era uncapped AP projectiles fired from high-velocity guns were able to penetrate about twice their calibre at close range: 100 m (110 yd). At longer ranges (500–1,000 m), this dropped to 1.5–1.1 calibres due to the poor ballistic shape and higher drag of the smaller-diameter early projectiles.

As the war progressed, vehicle armour became progressively thicker (and sloped) and early war AP and APHE was less effective against newer tanks. The initial response was to compensate by increased muzzle velocity in newly developed anti-tank guns. However, it was found that steel shot tended to shatter on impact at velocities greater than about 823 m/s (2700 feet/second).[4]

To counter this a cap of softer metal was attached to the tip of an AP (solid) round. The cap transferred energy from the tip of the shell to the sides of the projectile, thereby helping to reduce shattering. In addition, the cap appeared to improve penetration of sloped armour by deforming, spreading, and "sticking" to the armour on impact and thereby reducing the tendency of the shell to deflect at an angle. However, the cap structure of the APC shell reduced the aerodynamic efficiency of the round with a resultant reduction in accuracy and range.[4]

Later in the conflict, APCBC fired at close range from large-calibre, high-velocity guns (75–128 mm) were able to penetrate a much greater thickness of armour in relation to their calibre (2.5 times) and also a greater thickness (2–1.75 times) at longer ranges (1,500–2,000 m). Comparative testing of British 17-pounder (76 mm) gun and US Army APCBC rounds fired into captured German Panther tanks indicated the APCBC munitions were more accurate than late war armour-piercing discarding sabot (APDS) shot, though the lot used was described as sub-standard and the report made no determination of general APDS accuracy.[5]

APCBC shot was produced for a wide range of anti-tank artillery ranging from 2 pounders to the German 88 mm. This type of munition was also designated as APBC (Armour Piercing Ballistic Capped), in reference to the Soviet version of APCBC. APCBC shot was also used in naval armaments in World War II. After World War II, the trend in armour-piercing munitions development centred on sub-calibre projectiles. No tank guns designed since the late 1950s have used full-caliber AP, APC, or APCBC ammunition.[6]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 AMORDLISTA, Preliminär ammunitionsordlista (in Swedish). Sweden: Försvarets materielverk (FMV), huvudavdelningen för armémateriel. 1979. pp. 33, 35.

- ↑ Richardson v. United States, 72 Ct. Cl. 51 (1930)

- 1 2 "Juno Beach Centre – Anti-Tank Projectiles". Junobeach.org. Archived from the original on 2011-05-16. Retrieved 2010-06-12.

- ↑ U.S. Army Firing Test No. 3, U.S. Army Firing Tests conducted August 1944 by 12th U.S. Army Group at Isigny, France. Report of tests conducted during 20–21 August 1944.

- ↑ Orgokiewicz, p. 77.

References

- Orgokiewicz, Richard M. (1991), Technology of Tanks Volume I., Coulsdon: Jane's Information Group

- U.S. Army Firing Test No.3, 30 August 1944, archived from the original on 2009-08-12 – via www.wargaming.info

- Henry, Chris (2004), British Anti-tank Artillery 1939-45, New Vanguard 98, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 9781841766386