An outlaw, in its original and legal meaning, is a person declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, all legal protection was withdrawn from the criminal, so anyone was legally empowered to persecute or kill them. Outlawry was thus one of the harshest penalties in the legal system. In early Germanic law, the death penalty is conspicuously absent, and outlawing is the most extreme punishment, presumably amounting to a death sentence in practice. The concept is known from Roman law, as the status of homo sacer, and persisted throughout the Middle Ages.

A secondary meaning of outlaw is a person systematically avoiding capture by evasion and violence. These meanings are related and overlapping but not necessarily identical. A fugitive who is declared outside protection of law in one jurisdiction but who receives asylum and lives openly and obedient to local laws in another jurisdiction is an outlaw in the first meaning but not the second (one example being William John Bankes). A fugitive who remains formally entitled to a form of trial if captured alive but avoids capture because of the high risk of conviction and severe punishment if tried is an outlaw in the second sense but not the first (Sándor Rózsa was tried and sentenced merely to a term of imprisonment when captured).

In the common law of England, a "writ of outlawry" made the pronouncement Caput lupinum ("[Let his be] a wolf's head"), equating that person with a wolf in the eyes of the law. Not only was the subject deprived of all legal rights, being outside the "law", but others could kill him on sight as if he were a wolf or other wild animal. Women were declared "waived" rather than outlawed, but it was effectively the same punishment.[1]

Legal history

Ancient Rome

Among other forms of exile, Roman law included the penalty of interdicere aquae et ignis ("to forbid water and fire"). Such people penalized were required to leave Roman territory and forfeit their property. If they returned, they were effectively outlaws; providing them the use of fire or water was illegal, and they could be killed at will without legal penalty.[2]

Interdicere aquae et ignis was traditionally imposed by the tribune of the plebs and is attested to have been in use during the First Punic War of the third century BC by Cato the Elder.[3] It was later also applied by many other officials, such as the Senate, magistrates,[2] and Julius Caesar as a general and provincial governor during the Gallic Wars.[4] It fell out of use during the early Empire.[2]

England

In English common law, an outlaw was a party who had defied the laws of the realm by such acts as ignoring a summons to court or fleeing instead of appearing to plead when charged with a crime.[1] The earliest reference to outlawry in English legal texts appears in the 8th century.[5]

Criminal

The term outlawry refers to the formal procedure of declaring someone an outlaw, i.e., putting him outside legal protection.[1] In the common law of England, a judgment of (criminal) outlawry was one of the harshest penalties in the legal system since the outlaw could not use the legal system for protection, e.g., from mob justice. To be declared an outlaw was to suffer a form of civil or social[6] death. The outlaw was debarred from all civilized society. No one was allowed to give him food, shelter, or any other sort of support—to do so was to commit the crime of aiding and abetting, and to be in danger of the ban oneself. A more recent concept of "wanted dead or alive" is similar but implies that a trial is desired (namely if the wanted person is returned alive), whereas outlawry precludes a trial.

An outlaw might be killed with impunity, and it was not only lawful but meritorious to kill a thief fleeing from justice—to do so was not murder. A man who slew a thief was expected to declare the fact without delay; otherwise, the dead man's kindred might clear his name by their oath and require the slayer to pay weregild as for a true man.[7]

By the rules of common law, a criminal outlaw did not need to be guilty of the crime for which he was an outlaw. If a man was accused of treason or felony but failed to appear in court to defend himself, he was deemed convicted.[8] If he was accused of a misdemeanour, then he was guilty of a serious contempt of court which was itself a capital crime.

In the context of criminal law, outlawry faded out, not so much by legal changes as by the greater population density of the country, which made it harder for wanted fugitives to evade capture, and by the adoption of international extradition pacts. It was obsolete when the offence was abolished in 1938.[9][10][11] Outlawry was, however, a living practice as of 1855: in 1841, William John Bankes, who had previously been an MP for several different constituencies between 1810 and 1835, was outlawed by due process of law for absenting himself from trial for homosexuality and died in 1855 in Venice as an outlaw.

Civil

There was also a doctrine of civil outlawry. Civil outlawry did not carry the sentence of capital punishment. It was, however, imposed on defendants who fled or evaded justice when sued for civil actions like debts or torts. The punishments for civil outlawry were harsh, including confiscation of chattels (movable property) left behind by the outlaw.[12]

In the civil context, outlawry became obsolete in civil procedure by reforms that no longer required summoned defendants to appear and plead. Still, the possibility of being declared an outlaw for derelictions of civil duty continued to exist in English law until 1879 and in Scots law until the late 1940s. Since then, failure to find the defendant and serve process is usually interpreted in favour of the plaintiff, and harsh penalties for mere nonappearance (merely presumed flight to escape justice) no longer apply.

In other countries

Outlawry also existed in other ancient legal codes, such as the ancient Norse and Icelandic legal code.

In early modern times, the term Vogelfrei and its cognates came to be used in Germany, the Low Countries, and Scandinavia, referring to a person stripped of his civil rights being "free" for the taking like a bird.[13] In Germany and Slavic countries during the 15th to 19th centuries, groups of outlaws were composed of former prisoners, soldiers, etc. Hence, they became an important social phenomenon. They lived off of robbery, and local inhabitants from lower classes often supported their activity. The best known are Juraj Jánošík and Jakub Surovec in Slovakia, Oleksa Dovbush in Ukraine, Rózsa Sándor in Hungary, Schinderhannes and Hans Kohlhase in Germany.

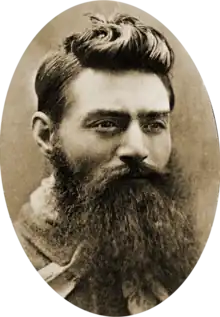

The concept of outlawry was reintroduced to British law by several Australian colonial governments in the late 19th century to deal with the menace of bushranging. The Felons Apprehension Act (1865 No 2a)[14] of New South Wales provided that a judge could, upon proof of sufficiently notorious conduct, issue a special bench warrant requiring a person to submit themselves to police custody before a given date, or be declared an outlaw. An outlawed person could be apprehended "alive or dead" by any of the Queen's subjects, "whether a constable or not", and without "being accountable for using of any deadly weapon in aid of such apprehension." Similar provisions were passed in Victoria and Queensland.[15] Although the provisions of the New South Wales Felons Apprehension Act were not exercised after the end of the bushranging era, they remained on the statute book until 1976.[16]

As a political weapon

There have been several instances in military and political conflicts throughout history whereby one side declares the other as being "illegal", notorious cases being the use of proscription in the civil wars of the Roman Republic. In later times there was the notable case of Napoleon Bonaparte whom the Congress of Vienna, on 13 March 1815, declared had "deprived himself of the protection of the law".[17]

In modern times, the government of the First Spanish Republic, unable to reduce the Cantonal rebellion centered in Cartagena, Spain, declared the Cartagena fleet to be "piratic", which allowed any nation to prey on it.[18] Taking the opposite road, some outlaws became political leaders, such as Ethiopia's Kassa Hailu who became Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia.[19]

Popular usage

Though the judgment of outlawry is now obsolete (even though it inspired the pro forma Outlawries Bill which is still to this day introduced in the British House of Commons during the State Opening of Parliament), romanticised outlaws became stock characters in several fictional settings. This was particularly so in the United States, where outlaws were popular subjects of newspaper coverage and stories in the 19th century, and 20th century fiction and Western movies. Thus, "outlaw" is still commonly used to mean those violating the law[20] or, by extension, those living that lifestyle, whether actual criminals evading the law or those merely opposed to "law-and-order" notions of conformity and authority (such as the "outlaw country" music movement in the 1970s).

See also

- Abrek

- American Old West

- Attainder

- Banditry

- Bill of attainder

- Border reivers

- Bounty hunter

- Brigandage

- Buccaneer

- Bushranger

- Cangaço

- Caput lupinum

- Civil death

- Dacoity

- List of depression-era outlaws

- Gangster

- List of Old West gunfighters

- Hajduk

- Highwayman

- Homo sacer

- Honghuzi ("red beards")

- Klepht

- Merchant raider

- Nazi hunter

- Nithing

- Ostracism

- Outlaw (stock character)

- Outlaw motorcycle club

- Piracy

- River pirate

- Robber baron (feudalism)

- Robber

- Shanlin

- Shifta

- Social banditry, a term invented by Eric Hobsbawm

- Thug

- Untouchability

- Vigilante

- Warg

- Wolf's Head, a Yale University senior society named for the legal maxim associated with outlawry

Notes

- 1 2 3 National Archives staff (26 January 2012). "Outlaws and outlawry in medieval and early modern England". British National Archives. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- 1 2 3 Berger, p. 507.

- ↑ Kelly 2006, p. 28.

- ↑ Caesar, Julius. De Bello Gallico, book VI, section XLIV.

- ↑ Carella, B (2015). "The Earliest Expression for Outlawry in Anglo-Saxon Law". Traditio. 70: 111–43. doi:10.1017/S0362152900012356. S2CID 233360789.

- ↑ Bauman, Zygmunt (n.d.). Modernity and Holocaust. p. .

- ↑ Pollock & Maitland 1968, p. 53.

- ↑ Archbold Criminal Pleading, Evidence and Practice (30th ed., 1938) p. 71

- ↑ Archbold (30th ed., 1938) p. 71

- ↑ Archbold (31st ed., 1943) p. 98

- ↑ Administration of Justice (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1938, section 12

- ↑ William Blackstone (1753), Commentaries on the Laws of England, Book 3, Chapter XIX "Of Process"

- ↑ Schmidt–Wiegand, Ruth (1998). "Vogelfrei". Handwörterbuch der Deutschen Rechtsgeschichte [Dictionary of the History of German Law]. 5: Straftheorie [Penal theory]. Berlin: Schmidt. pp. 930–32. ISBN 3-503-00015-1

- ↑ "Felons Apprehension Act (1865 No 2a)". New South Wales legislation. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ ANZLH E-Journal. "Outlawry in Colonial Australia: The Felons Apprehension Acts 1865–1899" (PDF). Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ ANZLH E-Journal. "Outlawry in Colonial Australia: The Felons Apprehension Acts 1865–1899" (PDF). Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ Timeline: The Congress of Vienna, the Hundred Days, and Napoleon's Exile on St Helena, Center of Digital Initiatives, Brown University Library

- ↑ "Cartagena Public Salvation Board" (pdf) (in Spanish). The Murciano Canton. 24 July 1873. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ Rubenson, King of Kings, pp. 36–39

- ↑ Black's Law Dictionary at 1255 (4th ed. 1951), citing Oliveros v. Henderson, 116 S.C. 77, 106 S.E. 855, 859.

References

- Berger, Adolf. "Interdicere aqua et igni". Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law. p. 507.

- Kelly, Gordon P. (2006). A history of exile in the Roman republic. Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 9780521848602.

- McLoughlin, Denis (1977). The Encyclopedia of the Old West. Taylor & Francisb. ISBN 9780710009630.

- Pollock, F.; Maitland, F. W. (1968) [1895]. The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I (2nd (1898), reprint ed.). Cambridge.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)