| Basingstoke Canal | |

|---|---|

The Basingstoke Canal passing through Woking | |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 31 miles (50 km) |

| Maximum boat length | 72 ft 6 in (22.10 m) |

| Maximum boat beam | 13 ft 6 in (4.11 m) |

| Locks | 29 |

| Status | Partially open |

| Navigation authority | The Basingstoke Canal Authority |

| History | |

| Principal engineer | John Smeaton |

| Other engineer(s) | Benjamin Henry Latrobe |

| Date of act | 1778 |

| Date completed | 1794 |

| Date closed | 1932 |

| Date restored | 10 May 1991 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Byfleet |

| End point | Greywell (originally Basingstoke) |

| Connects to | Wey Navigation |

Basingstoke canal map | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Basingstoke Canal is an English canal, completed in 1794, built to connect Basingstoke with the River Thames at Weybridge via the Wey Navigation.

From Basingstoke, the canal passes through or near Greywell, North Warnborough, Odiham, Dogmersfield, Fleet, Farnborough Airfield, Aldershot, Mytchett, Brookwood, Knaphill and Woking. Its eastern end is at Byfleet, where it connects to the Wey Navigation. This, in turn, leads to the River Thames at Weybridge. Its intended purpose was to allow boats to travel from the docks in East London to Basingstoke.

It was never a commercial success and, starting in 1950, a lack of maintenance allowed the canal to become increasingly derelict. After many years of neglect, restoration commenced in 1977 and on 10 May 1991 the canal was reopened as a fully navigable waterway from the River Wey to almost as far as the Greywell Tunnel. However its usage is currently still limited by low water supply and conservation issues.

History

With the end of the "canal mania", these £100 shares crashed to £30 in 1800 and £5 in 1834.[1]

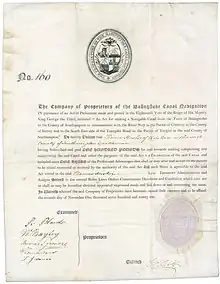

| Basingstoke Canal Act 1778 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An act for making a navigable canal from the town of Basingstoke, in the county of Southampton, to communicate with the river Wey, in the parish of Chertsey, in the county of Surrey; and to the south-east side of the turnpike road in the parish of Turgiss, in the said county of Southampton. |

| Citation | 18 Geo. 3. c. 75 |

| Basingstoke Canal Act 1793 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Long title | An act for effectually carrying into execution an act of parliament of the eighteenth year of the reign of his present Majesty, for making a navigable canal from the town of Basingstoke, in the county of Southampton, to communicate with the river Wey, in the parish of Chertsey, in the county of Surrey, and to the south east side of the turnpike road, in the parish of Turgiss, in the said county of Southampton. |

| Citation | 33 Geo. 3. c. 16 |

The canal was originally conceived as a way to stimulate agricultural development in Hampshire. It was authorised by the Basingstoke Canal Act 1778, the company being allowed to raise £86,000 (equivalent to £10,600,000 in 2019) by issuing shares, and an additional £40,000 (equivalent to £4,930,000 in 2019) if required.

The original proposed route was about 44 miles (71 km) long, running from Basingstoke to join the Wey and Godalming Navigations near Weybridge, with a large loop running to the north to pass around Greywell Hill. The loop cut through the grounds of Tylney Hall, owned by Earl Tylney, and he objected to the route. Due to this objection, difficulties in raising capital funding, and the American Revolutionary War being in progress, no construction took place for some time.

Nearly ten years later, a favourable forecast of expected traffic was published in 1787, and the canal committee took action. John Smeaton was appointed engineer, together with Benjamin Henry Latrobe,[2] and William Jessop was appointed as assistant engineer and made a survey. To avoid Tylney Hall the route was changed, with the original long contour-following route which had been surveyed around Greywell Hill being replaced by a tunnel through it, shortening the canal by nearly 7 miles (11 km).[3]

The contract for construction was awarded to John Pinkerton, part of a family of contractors who had often worked with Jessop, in August 1788.[4][5] Construction started in October 1788.[6]

The construction of Greywell Tunnel had been initially subcontracted to Charles Jones, although he had been dismissed by the Thames and Severn Canal company in 1788 after failing to complete the Sapperton Tunnel project, not entirely at his own fault. Jones was again dismissed in 1789 after the quality of the tunnel work was criticised.[7][8]

The canal was opened on 4 September 1794, but two sections of the bank collapsed shortly afterwards, and parts of it were closed until the summer of 1795.

One of the main cargoes carried from Basingstoke was timber,[9] along with agricultural products destined for London. A significant amount of traffic took place in the 1850s, carrying materials for the building of Aldershot Garrison, but this ended within a few years.[10] The Up Nately brickworks, to which a 100 metres (110 yd) long arm of the canal was built for access, opened in 1898 and in the following year produced 2 million bricks which were mostly transported on the canal. However, there were problems with the quality of the bricks and the brickworks went into liquidation in 1901 and closed in 1908.[11]

Otherwise, trade on the canal was never as intensive as had been predicted, and several companies attempted to run it, but each ended up bankrupt. The canal had started to fall into disuse even before the construction of the London and South Western Railway, which runs parallel to the canal along much of its length. In 1831, when plans for the railway were being developed, the canal company suggested instead that a link be built between the canal and the Itchen Navigation. The suggestion was rejected and the canal company agreed not to oppose the construction of the railway.[12] Commercial traffic on the canal mostly ended in 1910, although a low level of use would continue until the last cargo of timber to Woking in 1949.[13]

In the winter of 1913, Alec ("A J") Harmsworth attempted to navigate the canal in the narrowboat Basingstoke, carrying a cargo of sand. The intention of this trip was to prove, at the request of the then owner of the canal, that it was still navigable and so avoid the possibility of closure under the Railway and Canal Traffic Act 1854. Under that Act, if the canal were not used for five years then the land the canal was built on could be returned to the original owners.

It turned out not to be possible to navigate the entire length of the canal, but the boat did successfully pass through the Greywell Tunnel and was left at Basing Wharf over Christmas 1913. In January 1914 the boat finally reached Basing House where it was turned and returned to Basing Wharf to unload its cargo. Although it proved to be not possible to reach the end of the canal at Basingstoke Wharf, a legal appeal taking place at the same time established that the canal was private freehold property and therefore not subject to the Railway and Canal Traffic Act. The Basingstoke returned to its base at Ash Wharf, the last successful boat passage through the tunnel.[14]

During World War I the Royal Engineers took over the running of the canal and used it to transport supplies from Woolwich to the barracks at Aldershot, Crookham and Deepcut.[10] The canal was also used to train soldiers in boat handling.[15]

Harmsworth, the last trader working on the canal, purchased the canal in 1923, but only used the lower section (from the Wey as far as Woking) for limited commercial carrying and pleasure cruising. After part of the Greywell Tunnel collapsed in 1932, the canal to the west of that, including Basingstoke Wharf, was sold.[16]

The canal was not nationalised when the British Transport Commission was formed by the Transport Act 1947. After Harmsworth's death in the same year the canal was offered for sale again, and some interested enthusiasts and Inland Waterways Association members attempted to form a Basingstoke Canal Committee.[13] At the auction in 1949 they were under the impression that Joan Marshall of Fleet, who had offered to bid on their behalf, had secured the canal for them. However, it turned out that she had instead bought the canal for £10,000 (equivalent to £316,000 in 2019) on behalf of the New Basingstoke Canal Company, with the purchase having been financed by Mr S. E. Cooke, inventor of the Duracast fishing reel.[17][18]

This company (with Cooke as Managing Director and Joan Marshall as General Manager) attempted to continue maintaining the canal, including keeping the locks in working order. They tried to raise extra income from fishing and houseboat moorings[10] as well as water supply.[17] Unfortunately there was serious damage to Lock 22 in 1957, when some troops blew up the lock and drained the pound above, and a major breach above Ash Lock caused by flooding in 1968.[17] By the late 1960s the canal was essentially derelict, despite volunteer efforts to improve the situation.[6]

Restoration

In 1966 the Surrey and Hampshire Canal Society (now renamed the Basingstoke Canal Society) was formed by a group of local enthusiasts, with a view to reopening the derelict canal. They particularly campaigned to oppose proposals from the canal company in 1967 which would have retained only those sections of the canal useful for amenity and conservation purposes, culverting the water between them so that the land could be used for development. This would therefore have ended any possibility of through navigation.[17]

As a result of their campaigning, Surrey and Hampshire county councils began negotiations in 1970 to purchase the canal. However, those negotiations initially broke down which resulted in both of them announcing in February 1972 that they would apply to take over the canal via compulsory purchase orders. The orders were confirmed in February 1975 but did not need to be used, as Hampshire County Council had been able to take possession of their (western) part of the canal in November 1973 and Surrey County Council acquired their (eastern) part after negotiations in March 1976.[17]

In February 1977 a job creation project started with the aim of carrying out restoration work on the Deepcut flight of locks. The work was coordinated with the work of the canal society who organised work parties at weekends while the job creation team worked on weekdays.[19]

After about 18 years of restoration, 32 miles (51 km) of the canal were formally re-opened on 10 May 1991. The western section from North Warnborough to Basingstoke remains un-navigable from the point at which it enters the Greywell Tunnel. The tunnel partially collapsed in 1932 where it passes from chalk into clay geology, and is now inhabited by a protected bat colony making it unlikely that the tunnel will ever be restored. Some of the former canal basin at the western end has also been lost to modern development in and around Basingstoke.

The canal is now managed by the Basingstoke Canal Authority and is open to navigation throughout the year. Lock opening times are restricted due to the very limited water supply in an attempt to postpone summer closures which have plagued the canal since construction.[20] Boat numbers are also limited to 1,300 per year due to the fact that most of the canal has been designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest.[21]

Site of Special Scientific Interest

Two sections of the canal totalling 101.3 hectares (250 acres) are a Site of Special Scientific Interest and Nature Conservation Review site. These are the main length between Greywell and Brookwood Lye, and a short stretch between Monument Bridge and Scotland Bridge in Woking. It is the most botanically-rich aquatic area in England and flora include the nationally scarce hairlike pondweed and the nationally scarce tasteless water-pepper. The site is also nationally important for its invertebrates. There are 24 species of dragonfly and other species include two nationally rare Red Data Book insects.[22][23][24]

Eastwards from the mid point of the canal, it is surrounded by large areas of heathland. These are habitats for reptilian species, such as vipers and lizards, and birds such as nightjars, woodlarks and Dartford warblers. Much of this heath survives today due to its use since the late 19th century as military training areas.

Lost sections of the canal

The canal originally started from the centre of Basingstoke, but the first 5 miles (8 km) of route have now been lost. This section of the canal fell into disuse after the closure of the Greywell Tunnel, due to a lack of boat traffic, general neglect and a lack of water.

There were no locks on the canal after Ash, so the route generally followed the contours of the land with occasional cuttings, tunnels and embankments. The route can be partly determined by noting that the canal falls between the 75m and 80m contours on Ordnance Survey maps, and can be traced on historical map overlays as available at the National Library of Scotland.

The canal started at a basin, roughly where the present day Basingstoke Bus Station is located. From there it ran eastwards parallel to the River Loddon following Eastrop Way, before passing under the A339 Ringway East. It then made a long loop southwards and then eastwards again, partly on an embankment, passing over small streams and water meadows. The furthest visible sign of the canal today is the buried Red Bridge, which can be seen where Redbridge Lane turns northwards west of the Basing House ruins.

From here the canal route passed to the north of Basing House and through Old Basing village. Some remaining cuttings, which may contain water in wet weather, can be found just off Milkingpen Lane and behind the Belle View Road/Cavalier Road estate. There was then another southwards loop, crossing the routes of the present day A30 and M3 and then across the Lyde River at Hatch. From here the canal ran eastwards across fields, on an embankment towards Mapledurwell to then cross over another branch of the Lyde River. There was a short tunnel under Andwell Drove, and then the now demolished Penny Bridge leading under Greywell Road towards Up Nately.

From this point eastwards the canal is still in water and is maintained as a nature reserve, with the towpath as a public footpath leading to the western end of the Greywell Tunnel. Footpaths over the hill lead to the eastern end of the tunnel, in the centre of Greywell village, and the towing path continues onwards to the present day limit of navigation about 500 metres (550 yd) to the east.

The Basingstoke Canal Heritage Footpath roughly follows the canal route for 2 miles (3.2 km) from Festival Place to Basing House.

The main source of water for the western end of the canal appears to have been the natural springs within the Greywell Tunnel. Along the Basingstoke town section the River Loddon ran parallel with but not into the canal (the present day Eastrop Way, the former route of the canal, can be seen to be well above the river level) and there was also no connection with the River Lyde either at Huish Farm near Hatch (the river can be seen today to flow under the former canal bed just north of the M3) or at Mapledurwell. There are, however, small streams flowing into the canal at Fleet and Aldershot.

In order to alleviate the lack of water in the western part of the canal, a stop lock was built just to the east of the Greywell Tunnel to raise the water level by about 30 centimetres (1 ft). However this was a long section of canal with many embankments and it is likely that this was a cheap short term measure, instead of improving the water supply or properly fixing leaks.

Plans

There have been proposals to reconnect Basingstoke with the surviving section of the canal several times in the past, and this remains a long term aim of the Basingstoke Canal Society.[25] However, the bat population now established in the Greywell Tunnel makes it unlikely that the tunnel will ever be able to be reopened.

Another possible idea that has been considered in the past, and is still a long term ambition today, is to connect the remaining canal to the Kennet and Avon Navigation via a new Berks and Hants Canal. This link was proposed three times between 1793 and 1810, and a route was even surveyed by John Rennie in 1824, but following opposition from landowners was eventually rejected by Parliament in 1824 and 1826.[25][26] This route would allow the tunnel to remain undisturbed.

The Basingstoke Canal Authority

The canal is owned by both Hampshire County Council and Surrey County Council, with each authority owning the land within their jurisdiction. Until 1990, both councils managed their own sections separately. It was decided that a central body should manage the entire waterway and the Basingstoke Canal Authority was formed.

In 1993, the canal visitor centre at Mytchett was opened which now also acts as the central offices of the canal authority.[27]

The canal authority staff are employed, administered and supported by Hampshire County Council; however, the centre belongs to Surrey County Council. Each county council allocates revenue money to the canal authority, as well as the six riparian district/borough authorities through which the canal passes. The canal authority partnership is governed by the Basingstoke Canal Joint Management Committee[28] – a joint committee of Surrey County Council formed of council members from each of the local authority partners.

The structure of the canal authority was last reviewed in 2011,[29] with the two county councils allocating client officers from their Countryside teams to lead the strategic direction for the canal, taking on part of the former Canal Director's role. The canal authority is now formed of one canal manager, a senior administration officer and assistant, visitor services manager and visitor services officer. The canal is maintained by a team of five canal rangers and one senior ranger, supported by a part-time seasonal lock keeper.

Architectural features

A notable feature of the canal is the large number of concrete bunkers known as pillboxes still visible along its length; these were built during World War II as part of the GHQ Line to defend against an expected German invasion.

Odiham Castle is situated at the Greywell (Basingstoke) end of the canal. The canal runs through part of the castle's bailey.[30]

The Greywell Tunnel (now disused), at 1,230 yards (1,120 m) long, was the 12th longest canal tunnel in Great Britain.[31]

Gallery

Inside the Greywell Tunnel (east end)

Inside the Greywell Tunnel (east end) The eastern portal of Greywell Tunnel

The eastern portal of Greywell Tunnel View from the 'Lift Bridge' in North Warnborough

View from the 'Lift Bridge' in North Warnborough Basingstoke Canal Centre, Mytchett, Surrey

Basingstoke Canal Centre, Mytchett, Surrey Guildford Road Bridge, Basingstoke Canal, Frimley Green, Surrey

Guildford Road Bridge, Basingstoke Canal, Frimley Green, Surrey Dry dock

Dry dock A lock

A lock Repairs being carried out in 2012

Repairs being carried out in 2012

See also

Bibliography

- Hadfield, Charles (1969). The Canals of South and South East England. David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4693-8.

- Skempton, Sir Alec; et al. (2002). A Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers in Great Britain and Ireland: Vol 1: 1500 to 1830. Thomas Telford. ISBN 0-7277-2939-X.

- Denton, Tim (2009). Wartime Defences on the Basingstoke Canal. Pillbox Study Group.

- Jebens, Dieter (2004). Guide to the Basingstoke Canal (2nd ed.). Basingstoke Canal Authority and the Surrey and Hampshire Canal Society.

- Jebens, Dieter; Cansdale, Roger (2007). Basingstoke Canal. Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-3103-1.

References

- ↑ Spruce, Derek (September 2018). "Basingstoke Canal" (PDF). Institute of Historical Research.

- ↑ Fazio, Michael W. (2006). The domestic architecture of Benjamin Henry Latrobe. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 601.

- ↑ Hadfield 1969, p. 152

- ↑ Hadfield 1969, pp. 151–152

- ↑ "Surrey & Hampshire Canal Society — Engineering Aspects — The Greywell Tunnel". Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- 1 2 "Basingstoke Canal - Canal Story". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2006.

- ↑ Hadfield 1969, p. 153

- ↑ Skempton 2002, p. 528

- ↑ Michael E Ware (1989). Britain's Lost Waterways. pp. 40–43. ISBN 0-86190-327-7.

- 1 2 3 "Greywell Tunnel Basingstoke Canal". Subterranea Britannica. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ↑ "Basingstoke Canal Bulletin No.34" (PDF). Basingstoke Canal Society. Retrieved 23 December 2021.

- ↑ Patterson, A. Temple (1966). A History of Southampton 1700-1914 Vol.I An Oligarchy in Decline 1700-1835. The University of Southampton. p. 167.

- 1 2 "Basingstoke Canal". skippy.org.uk. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ↑ "Basingstoke Canal Society - The Last Attempt to get to Basingstoke". Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ↑ Anthony Burton (1989). The Great Days of the Canals. p. 169. ISBN 0-7153-9264-6.

- ↑ Hadfield 1969, p. 158

- 1 2 3 4 5 Crocker, Glenys (1977). The History of the Basingstoke Canal (2nd ed.). Surrey & Hampshire Canal Society. Archived from the original on 11 August 2013. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ↑ "1949 And All That". Newsletter No.117. Surrey and Hampshire Canal Society. September 1984. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ↑ Vine, P. A. L. (1994). London's Lost Route to Basingstoke (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-0750903592.

- ↑ "Basingstoke Canal Conservation Management Plan" (PDF). Hampshire CC. November 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015.

- ↑ "Designated Sites View: Basingstoke Canal". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ↑ "Map of Basingstoke Canal". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- ↑ "Basingstoke Canal citation" (PDF). Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 2 November 2018.

- 1 2 "Basingstoke Canal – The last 5 miles". Basingstoke Canal Society. 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ↑ "Imagined canals". Waterfront. Canal and River Trust. 5 July 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- ↑ Jebens, Dieter (2015). A Guide to the Basingstoke Canal. Basingstoke Canal Society. p. 15.

- ↑ "Basingstoke Canal Joint Management Committee". Surrey County Council. 15 November 2015. Archived from the original on 15 November 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ↑ "Minutes of the Basingstoke Canal Joint Management Committee" (PDF). Surrey CC. 11 February 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2015.

- ↑ Willoughby, Rupert (1998). A key to Odiham castle. p. 19.

- ↑ "Greywell Tunnel". Hampshire Chronicle. 11 April 1984. p. 6.

External links

- The Basingstoke Canal Authority Archived 10 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Surrey and Hampshire Canal Society

- The River Wey and Wey Navigations Community Site – a non-commercial site of over 200,000 words all about the adjacent Wey Navigation with a section about the Basingstoke Canal

- Basingstoke Canal Walk (Long Distance Walkers' Association)

- ITV Documentary (video clip)

- Canal Navigations — detailed photographic essay covering the now 'lost' part of the canal between Greywell and Basingstoke