Modern basset horn (German and French System, Schwenk & Seggelke) | |

| Other names | it: corno di bassetto, de: Bassetthorn, fr: cor de basset |

|---|---|

| Classification | Woodwind, clarinet family |

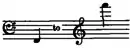

| Playing range | |

Ambitus written  Ambitus Bassethorn in F, sounding | |

| Related instruments | |

| Clarinet d'amore, Alto clarinet, bass clarinet, tenor saxophone | |

| Musicians | |

| Suzanne Stephens, Sabine Meyer, Stephan Siegenthaler, Alessandro Carbonare Clarinet Trio | |

| Composers | |

| Carl Stamitz, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Alessandro Rolla, Felix Mendelssohn, Richard Strauss, Roger Sessions, Karlheinz Stockhausen | |

| Builders | |

| Schwenk & Seggelke, Herbert Wurlitzer, Leitner & Kraus, Buffet Crampon, Selmer Company | |

| Sound sample | |

| More articles or information | |

|

Historical instruments

Museum of Musical Instruments, Berlin: 18th-century basset horns (with clarinets, a flute, and bassoons)  Mozart Divertimento for 3 Basset Horns (Kay Lipton - "Art Informed By Music") | |

The basset horn (sometimes hyphenated as basset-horn) is a member of the clarinet family of musical instruments.

Construction and tone

Like the clarinet, the instrument is a wind instrument with a single reed and a cylindrical bore. However, the basset horn is larger and has a bend or a kink between the mouthpiece and the upper joint (older instruments are typically curved or bent in the middle), and while the clarinet is typically a transposing instrument in B♭ or A (meaning a written C sounds as a B♭ or A), the basset horn is typically in F (less often in G). Finally, the basset horn has additional keys for an extended range down to written C, which sounds F at the bottom of the bass staff. In comparison, the alto clarinet typically extends down to written E♭, which sounds G♭, one semitone higher than the basset horn.[1] The timbre of the basset horn is similar to the alto clarinet's, but darker. Basset horns in A, G, E, E♭, and D were also made; the first of these is closely related to the basset clarinet.[2][3]

The basset horn is not related to the horn, or other members of the brasswind family (Sachs-Hornbostel classification 423.121.2 or 423.23); it does, however, bear a distant relationship to the hornpipe and cor anglais. Its name probably derives from the resemblance of early, curved versions to the horn of some animal.[4]

Some of the earliest basset horns, which are believed to date from the 1760s, bear an inscription "ANT et MICH MAYRHOFER INVEN. & ELABOR. PASSAVII", which has been interpreted to mean they were made by Anton and Michael Mayrhofer of Passau.[5]

Modern basset horns can be divided into three basic types, distinguished primarily by bore size and, consequently, the mouthpieces with which they are played:

- The small-bore basset horn has a bore diameter in the range of 15.5 to 16.0 mm (0.61–0.63 in) (still somewhat larger than a soprano clarinet bore, though it is often erroneously thought to be the same; even a large bore English clarinet, such as the old B&H 1010 design has a smaller bore of 15.3 mm (0.60 in)). It is played with a B♭/A clarinet mouthpiece. Only the Selmer Company (Paris) and Stephen Fox (Canada) currently make this model.[6]

- The medium-bore basset horn has a bore diameter in the region of 17.0 mm (0.67 in) or slightly less. This is the most common type made by German-system manufacturers (e.g., Otmar Hammerschmidt (Austria)). Since no French-style mouthpiece with an appropriate bore is mass-produced, this model requires a matching German basset-horn mouthpiece. (This model is not usually recognized in North America, where it is confused with the large-bore type described below.) Stephen Fox currently makes this model also.[6]

- The large-bore basset horn, with a bore diameter of about 18.0 mm (0.71 in) and played with an alto-clarinet mouthpiece, is in constructional terms an alto clarinet pitched in F and with the extra basset notes. The Leblanc basset horns (bores about 18.0 to 18.2 mm (0.71–0.72 in)) are of this type.[6]

The current Buffet basset horn could be called a hybrid "medium-large bore" model, since it uses an alto-clarinet mouthpiece but has a bore diameter around 17.2 mm (0.68 in).[7][8]

Repertoire

A number of composers of the classical period wrote for the basset horn, and the famous 18th-century clarinettist Anton Stadler, as well as his younger brother Johann, played it. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was by far the most notable composer for the basset horn, including three basset horns in the Maurerische Trauermusik (Masonic Funeral Music), K. 477, and two in both the Gran Partita, K. 361, and the Requiem, K. 626, and several of his operas, such as Die Entführung aus dem Serail, La Clemenza di Tito which features Vitellia's great aria "Non più di fiori" with basset-horn obbligato, and Die Zauberflöte, where they prominently accompany the March of the Priests, as well as chamber works. He wrote dozens of pieces for basset horn ensembles. (His Clarinet Concerto in A Major, KV 622, however, appears originally to have been written for a clarinet with an extended lower range, a basset clarinet in A, though there is an earlier version of part of the first movement, KV 621b in the Köchel catalogue of Mozart's works, scored for G basset horn and pitched a major second lower, in the key of G major.) The Clarinet Quintet in A major (K. 581) has also been performed on basset horn by Teddy Ezra with other members of the Else Ensemble.[9]

Other early works for basset horn include a concerto for basset horn in G and small orchestra by Carl Stamitz, which has been arranged for conventional basset horn in F (it has been recorded on this instrument by Sabine Meyer), and a concerto in F by Heinrich Backofen.

In the 19th century Felix Mendelssohn wrote two pieces for basset horn, clarinet, and piano (opus 113 and 114). These were later scored for string orchestra. Franz Danzi wrote a Sonata in F, for basset horn and piano, Op. 62 (1824) Antonín Dvořák attempted a half-hearted revival, using the instrument in his Czech Suite (1879), in which he specifies that an English horn (cor anglais) may be used instead, but the instrument was largely abandoned until Richard Strauss took it up once more in his operas Elektra (1909), Der Rosenkavalier, Die Frau ohne Schatten, Daphne, Die Liebe der Danae, and Capriccio, and several later works, including two wind sonatinas (Happy Workshop and Invalid's Workshop). Franz Schreker also employed the instrument in a few works including the operas Die Gezeichneten and Irrelohe. Roger Sessions included a basset horn in the orchestra of his Violin Concerto (1935), where it opens the slow movement in a lengthy duet with the solo violin. In the last quarter of the 20th century and first decade of the 21st, Karlheinz Stockhausen wrote extensively for basset horn, giving it a prominent place in his cycle of operas Licht and other pieces.

Other works

- "Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind" for solo clarinetist (soprano clarinets, basset horn, and bass clarinet) and string quartet by Osvaldo Golijov; later arranged for solo clarinetist and string orchestra.[10]

- Serenade on Carl Maria von Weber's Oberon for basset horn and two guitars, op. 28, written by Heinrich Neumann.

- Etudes for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 39 (1992) by Peter Schat calls for 3 basset horns in the orchestra.

- Serenade for 12 Instruments, Op. 61b (1915) by Josef Holbrooke calls for both corni di bassetto and oboe d'amore.

- Alessandro Rolla – Concerto in F Major BI. 528 for basset horn and orchestra

- Bertold Hummel – Concertino for basset horn and strings Op. 27a (1964)[11]

- George Benjamin's first opera Into the Little Hill

- In his enormous Gothic Symphony Havergal Brian enlists two basset horns.

- Samuel Andreyev - La pendule de profil for basset horn, bassoon, viola, cello and double bass

- Michael Schneider - Licht bei Vermeer for basset horn, vibraphone and 8 voices

- Howard J. Buss - "In Memoriam" for basset horn and piano (2015)

Basset horn soloists and ensembles

The Lotz Trio performs on replicas of the basset-horns made by the 18th-century instrument maker Theodor Lotz of Pressburg (Bratislava) and Vienna. The ensemble presents a repertoire of popular 18th-century wind harmonias (known in German as Harmoniemusik) represented predominantly by Mozart's music. However, the ensemble also performs music by other central-European composers – Georg Druschetzky, Martín I Soler, Anton Stadler, Vojtech Nudera, Johann Josef Rösler and Anton Wolanek.

The Prague Trio of Basset-horns, based in the Czech Republic, has a repertoire of music written or transcribed for three basset horns, by composers including Mozart, Scott Joplin, and Paul Desmond.

Suzanne Stephens was a leading basset-horn specialist in contemporary music. Starting in 1974, the German Karlheinz Stockhausen composed many new works for her, including a large number for basset-horn with a solo rolo in his opera LIGHT. Other interprets of Stockhausens music are among others the Dutch Fie Schouten and the Italian Michele Marelli.

Alternative usage

The Italian name for the instrument, corno di bassetto, was used by Bernard Shaw as a pseudonym when writing music criticism.

See also

- Alto clarinet (a somewhat similar instrument that does not have the lower extension keys and has a bass range that typically begins one semitone higher,[12] more commonly used in concert bands than as a solo instrument, in chamber music, or in orchestras[13])

References

- ↑ "Alto Clarinet vs Basset Horn: Can You Hear the Difference?". YouTube.

- ↑ Lawson, Colin (November 1987). "The Basset Clarinet Revived". Early Music. 15 (4): 487–501. doi:10.1093/earlyj/XV.4.487.

- ↑ Rice, Albert R. (September 1986). "The Clarinette d'Amour and Basset Horn". Galpin Society Journal. 39: 97–111. doi:10.2307/842136. JSTOR 842136.

- ↑ Jeremy Montagu, "Basset Horn", The Oxford Companion to Music, edited by Alison Latham (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2002).

- ↑ Nicholas Shackleton. "Basset-horn", Grove Music Online, ed. Deane Root (accessed 25 March 2011), grovemusic.com Archived 2008-05-16 at the Wayback Machine (subscription access).

- 1 2 3 Fox, Stephen. "Basset Horn". Sfoxclarinets.com. Retrieved 2020-12-29.

- ↑ "The Clarinet BBoard".

- ↑ "Alto Clarinet vs Basset Horn: Can You Hear the Difference?". YouTube.

- ↑ Israel Broadcasting Authority, Kol Ha-Musika Etnachta broadcast, 30 May 2016

- ↑ "Oakland Symphony performs a clarinetist's 'Dream'". Inside Bay Area. 2007-03-21. Retrieved 2007-03-21.

- ↑ Boosey & Hawkes

- ↑ "Alto Clarinet vs Basset Horn: Can You Hear the Difference?". YouTube.

- ↑ "The Clarinets - Alto clarinet and Bassett Horn".

Further reading

- Dobrée, Georgina. 1995. "The Basset Horn". In The Cambridge Companion to the Clarinet, edited by Colin Lawson, 57–65. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47066-8 (cloth); ISBN 0-521-47668-2 (pbk).

- Grass, Thomas, Dietrich Demus, and René Hagmann. 2002. Das Bassetthorn: seine Entwicklung und seine Musik. Norderstedt: Books on Demand. ISBN 3-8311-4411-7.

- Hoeprich, Eric. 2008. The Clarinet. The Yale Musical Instrument Series. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10282-6.

- Jungerman, Mary C. 1999. "The Single-reed Music of Karlheinz Stockhausen: How Does One Begin?". The Clarinet 27: 52.

- Weston, Pamela T. 1997. "Stockhausen's Contributions to the Clarinet and Basset Horn....". The Clarinet 25, no. 1:60–61.