Remains of the Baths of Constantine in the 16th century | |

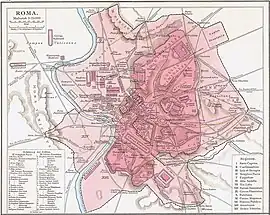

Baths of Constantine Shown in ancient Rome | |

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Location | Rome, Italy |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°53′54″N 12°29′14″E / 41.8983°N 12.4873°E |

Baths of Constantine (Latin, Thermae Constantinianae) was a public bathing complex built on Rome's Quirinal Hill, beside the Tiber River, by Constantine I, probably before 315.[1]

Ancient Constantinople and Arles also had complexes known as Baths of Constantine.

History

Construction and plan

The last of Rome's bath complexes, they were constructed in the irregular space enclosed by the vicus Longus, the Alta Semita, the clivus Salutis and the vicus laci Fundani. And as this was on a side-hill, it was necessary to demolish the 4th-century houses then on the site (beneath which are ruins of second- and third-century houses) and make an artificial level over their ruins.[2] Because of these peculiar conditions, these thermae differed in plan from all others in the city – no anterooms were provided on either side of the caldarium, for instance, since the building was too narrow. The building was oriented north–south so as to heat it using the sun, with principal entrances on the west side, where there was a flight of steps down from the hill's summit to the Campus Martius, and on the middle of the north side.

As the main structure occupied all the space between the streets on the east and west, the ordinary peribolus was replaced by an enclosure across the front which was bounded on the north by a curved line, an area now occupied by the Palazzo della Consulta. The frigidarium seems to have had its longer axis aligned north and south instead of east and west, and behind it were tepidarium and caldarium, both circular in shape.

The only reference to these baths in ancient literature is in Ammianus Marcellinus,[3] though they are mentioned in the Einsiedeln Itinerary (1.10; 3.6; 7.11).

5th century

The baths suffered greatly from fire and earthquake in the century after their construction. They were restored in 443 by the city prefect Petronius Perpenna Magnus Quadratinus,[4] at which time it is probable that the colossal statues of the Dioscuri and horses, now in the Piazza del Quirinale, were set up within them.[5] The Baths of Constantine probably remained in use until the Gothic War (535–554), when all but one of the aqueducts to the city of Rome were cut by the Ostrogoths.

Rediscovery

Enough of the structure was standing at the beginning of the sixteenth century to permit plans and drawings by architects of that period; these are the chief sources of our knowledge of the building.[6] The remains were almost entirely destroyed in 1605–1621 during the construction of the Palazzo Rospigliosi, but some traces were found a century later,[7] and since 1870.[8] Some of these can now be seen beneath the Casino dell'Aurora.

Art works

Notable art works were found on the site of these thermae, among them:

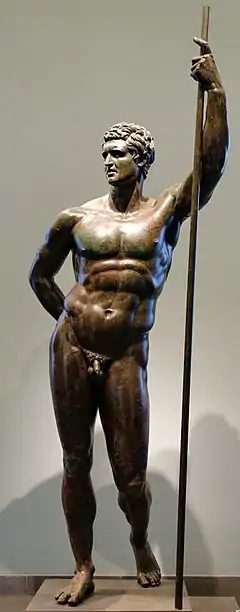

- The bronze statues of a boxer and an unidentified Hellenistic Prince now in the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme of the National Roman Museum.[9]

- Two statues of Constantine, one now housed in the narthex of the Basilica di San Giovanni in Laterano, and the other in the Capitoline Museums with a statue of his son Constantius II.[10]

- Frescoes, in the Palazzo Rospigliosi until c.1929[11] and now in the Museo delle Terme - these belong to an earlier building, perhaps the Domus Claudiorum.

- The allegorical statues of the Nile and Tiber rivers flanking the staircase leading to the Palazzo Senatorio in the Piazza del Campidoglio.[12]

- The oversized statues of Castor and Pollux known as the "Horse Tamers" which decorate the Fontana di Monte Cavallo in Piazza del Quirinale.[12]

_03.jpg.webp) Castor & Pollux with their horses in Piazza del Quirinale

Castor & Pollux with their horses in Piazza del Quirinale_-_Lateral_View.jpg.webp) Boxer at Rest

Boxer at Rest Hellenistic Prince

Hellenistic Prince The "Tiber" in the Campidoglio

The "Tiber" in the Campidoglio The "Nile" in the Campidoglio

The "Nile" in the Campidoglio Constantine in the Lateran Basilica

Constantine in the Lateran Basilica

See also

Sources

- For the thermae in general, see H. Jordan, Topographie der Stadt Rom, pp. 438‑441; Rheinisches Museum fur Philologie, Neue Folge, 1894, 389‑392; Jord. II.526‑528; O. Gilbert, Geschichte und Topographie der Stadt Rom in Altertum (Leipzig 1883–1890), vol. III p. 300; Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft, vol. IV, 962‑963; Reber, Die Ruinen Roms, 2nd ed. (Leipzig, 1879), pp. 496‑500; Canina Ed. iv. pls. 220‑222; Memorie della Classe di Scienze Morali, Storiche e Philologiche della R. Accademia dei Lincei, series 5, 17 (1909), pp. 534, 535.

- , from Platner's Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome

References

- ↑ Aurelius Victor Caes. 40: a quo ad lavandum institutum opus ceteris haud multo dispar; Not. Reg. VI

- ↑ Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma 1876, pp. 102‑106

- ↑ xxvii.3.8: cum collecta plebs infima domum prope Constantinianum lavacrum iniectis facibus incenderat

- ↑ CIL VI, 1750

- ↑ Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archaologischen Instituts, Romische Abteilung, 1898, pp. 273‑274; 1900, pp. 309‑310

- ↑ See especially Serlio, Architettura iii.92; Palladio, Le Terme, pl. XIV.; Dupérac, Vestigii, pl. 32; R. Lanciani, Storia degli Scavidi Roma (Rome, 1902-12), Vol. III, pp.196‑197; Ant. van den Wyngaerde, Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma 1895, pls. VI.-xiii.; H. Jordan, Topographie der Stadt Rom in Altertum (Berlin: 1906), Vol. I Part 3, p. 439 n 131

- ↑ Bullettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale di Roma, 1895, p. 88; H. Jordan, Topographie der Stadt Rom, Vol. I, Part 3, p. 440, n133

- ↑ Notizie degli Scavi di Antichita comunicate alla R. Accademia dei Lincei 1876, 55, 99; 1877, 204, 267; 1878, 233, 340

- ↑ Lawrence Richardson (1992). A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 390–391.

- ↑ CIL VI, 1148, CIL VI, 1149, CIL VI, 1150; F. Matz and F. von Duhn, Antike Bildwerke in Rom (1881-1882), p. 1346; W. Helbig, Fuhrer durch die offentlichen Sammlungen Roms, Third edition 3 (revised by Amelung), Vol. I p. 411

- ↑ Matz-Duhn, p. 4110; Papers of the British School at Rome Vol. VII, pp. 40‑44; Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archaologischen Instituts, Romische Abteilung, 1911, p. 149

- 1 2 "Baths of Constantine". archive1.village.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2020-01-02.