| Battle of Caesar's Camp (1793) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Flanders campaign of the War of the First Coalition | |||||||

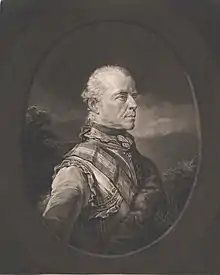

.JPG.webp) Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld planned to crush the French army, but his opponents escaped. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 43,000 | 35,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| light | light, 3 guns | ||||||

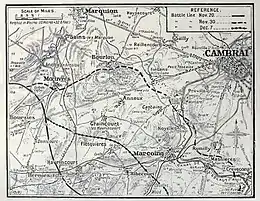

The Battle of Caesar's Camp (7–8 August 1793) saw the Coalition army led by Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld try to envelop a Republican French army under Charles Edward Jennings de Kilmaine. Numerically superior Habsburg Austrian, British and Hanoverian columns converged on the fortified French camp, but Kilmaine wisely decided to slip away toward Arras. The War of the First Coalition skirmish was fought near Cambrai, France, and the village of Marquion located 12 kilometres (7 mi) northwest of Cambrai.

Adam Philippe, Comte de Custine, the previous commander of the Army of the North was ordered to Paris, where he was soon arrested and guillotined. Kilmaine was requested to lead the army until a permanent replacement arrived. Two Austrian columns set out to strike the French front while a British and Hanoverian column under Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany marched completely behind the French army. Though one representative on mission urged Kilmaine to attack, the general determined to escape to the west. On 8 August, the Coalition trap snapped shut on only two battalions and even these got away when Kilmaine intervened with his massed cavalry. Kilmaine was dismissed and later arrested, though he avoided the guillotine and served in Italy under Napoleon Bonaparte in 1796.

Background

In May 1793, Lyon, the Vendée, Toulon, and Marseilles burst into revolt against the First French Republic. Meanwhile, the French were defeated by the Sardinians at the Battle of Saorgio on 12 June and the War of the Pyrenees was going badly when a Spanish army invaded Roussillon. The situation looked hopeless for Revolutionary France. The overthrow of the moderate Girondin faction in the Insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793 meant that the extreme Jacobins took control of the National Convention.[1]

In the Battle of Famars on 23 May 1793, the Coalition army led by Prince Coburg drove away the French Army of the North under François Joseph Drouot de Lamarche and began the Siege of Valenciennes.[2] Lamarche soon stepped down and was replaced by Custine, who took command on 27 May. Custine reorganized, fully equipped, and better disciplined the French army. However, the Jacobins mistrusted officers who served in the old Royalist army and continually denounced Custine.[3] The Minister of War Jean Baptiste Noël Bouchotte undermined Custine through his agents in the army.[4] On 12 July, the Siege of Condé ended when the fortress surrendered to the Allies. On 16 July, the Committee of Public Safety summoned Custine to Paris and on 21 July he was arrested and imprisoned.[5] The surrender of Mainz on 23 July and Valenciennes on 27 July[6] doomed Custine in the eyes of the Jacobins and he was executed by guillotine on 27 August.[5]

Jean Nicolas Houchard was selected to replace Custine, but he was not able to assume the command right away. Meanwhile, Kilmaine, who commanded the Army of the Ardennes, had been favored by the representatives on mission for some minor successes. Kilmaine arrived on 15 July 1793 at Cambrai to take temporary command. On 30 July, the Army of the North numbered 129,891, not including two attached divisions of the Army of the Ardennes. These were the 8,682-man 1st Division and the 11,787-strong Maubeuge Division. The Army of the Ardennes only included its 27,287-man 2nd Division, most of which was dispersed in garrisons. Though the two French armies included 177,649 soldiers, most of the troops were widely distributed in various fortresses and camps, so that the main body under Kilmaine consisted of only 35,177 men in the Camp de César (Caesar's Camp).[7]

After taking Valenciennes, the Coalition leaders were seized by indecision about where to strike next. The Austrians had already agreed to lend 10,000 troops to the Duke of York for the purpose of capturing Dunkirk. Coburg did not like this strategy and submitted his own plan which was to advance southeast toward Maubeuge while the Prussian army thrust southwest from Mainz toward Saarlouis. York disagreed with this plan and was sustained by a message from Vienna on 6 August. Johann Amadeus von Thugut, adviser to Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor, wished for the Prussian army to cooperate with Austria in the conquest of Alsace, for Coburg to move against Le Quesnoy, and for York to operate against Dunkirk. Coburg grudgingly acquiesced, but it was decided to first bring about a major battle with the French army.[8]

Action

According to historian Ramsay Weston Phipps, Kilmaine had 35,000 troops to defend Caesar's Camp, which was also called the Camp of Paillencourt. If forced to retreat, he planned to move south through Honnecourt-sur-Escaut and Le Catelet.[9] Digby Smith credited Kilmaine with only 25,435 soldiers.[10] The French position formed a four-sided figure with its front facing east behind the Scheldt (Escaut) River with the fortress of Bouchain on its left and the fortress of Cambrai on its right. The northern side was protected by the Sensée River and coincided with Marshal Claude de Villars' famous lines of La Bassée from the War of the Spanish Succession. The south side between Cambrai and Marquion was guarded by the Bourlon heights. The west side was protected by the Agache River which flows north into the Sensée near Arleux. The Scheldt was flooded and all crossings of the Scheldt and Sensée were covered by fortifications and abatis. The Bourlon heights were similarly fortified.[8]

Coburg conceived a plan to crush the French army.[11] On 6 August 1793, Coburg put the entire Coalition army in motion. The Duke of York led 22,000 men to an assembly point at Villers-en-Cauchies. A Hessian column covered York's far left flank in the direction of Le Quesnoy.[12] According to Phipps, on 7 August York's left flank column of 25,000 men marched toward Crèvecœur-sur-l'Escaut. It was intended to envelop the French southern flank and strike Kilmaine's right rear. Two more columns numbering a total of 16,000 soldiers started from Hérin. Wenzel Joseph von Colloredo's center column and François Sébastien Charles Joseph de Croix, Count of Clerfayt's right flank column aimed to cross the Scheldt north of Cambrai. Smaller forces were ordered to launch false attacks along the Sensée.[13] Historian John Fortescue wrote that York's column numbered only 14,000 men. He credited Colloredo with 9,000 soldiers, and Clerfayt with 12,000 troops, and that the two were ordered to force a crossing of the Scheldt. York's chief-of-staff James Pulteney believed that the French would try to avoid combat and asked that York's column be assigned more cavalry. This request was denied.[14]

It was very hot on 7 August, so that many men died from the heat. By the evening, Clerfayt reached Thun-Saint-Martin on the Scheldt. Farther south, Colloredo passed through Naves[12] and reached the Scheldt, but neither column crossed the river that day. York's column crossed the Scheldt at Crèvecœur and Masnières after a 12 mi (19 km) march[13] that took 11 hours to accomplish, so that the exhausted troops could go no farther.[14] That day, Kilmaine formed a division of 3,000 French cavalry and used it to delay York's march by mounting feint attacks and forcing the Allies to deploy.[15] In the evening, the 15th Light Dragoons at the front of York's column went to water their horses in the Scheldt. The 15th saw some enemy cavalry, and without waiting for support from the 16th Light Dragoons, the regiment charged and drove off the French. For a loss of only 2 men wounded, the 15th inflicted serious losses on the French and captured 2 officers and 60 enlisted men.[12]

Kilmaine recognized that his army was being enveloped and called a council of war. Representative on mission Pierre Delbrel urged that the French army should leave token forces to observe Clerfayt and Colloredo, and hurl itself on York's column. After smashing York's column, the French could then turn against the other two columns. Kilmaine argued that his troops were not able to carry out such a complicated maneuver, and that he did not have sufficient cavalry strength. Rather than falling back toward Paris, Kilmaine adopted a plan to retreat to the west and assume a new position behind the Scarpe River between Arras and Douai. This would place his army on the flank of any Allied advance toward Paris, while having the fortress of Lille behind him. The French withdrawal began that night.[16]

The French army was in motion at dawn on 8 August. When the York's column reached Cantaing-sur-Escaut, he found the French gone.[12] Though the other two columns soon halted, York kept going in the direction of Marquion.[17] For the pursuit, York gathered up 2,000 British cavalry, including the Blues, Scots Greys, and Inniskilling Dragoons, three regiments of dragoon guards, and four regiments of light dragoons.[18][note 1] The brigade of Ralph Dundas included the 7th, 11th, 15th, and 16th Light Dragoons.[19] When York arrived at Marquion, the French had set the buildings on fire and broken the bridge over the Agache in order to block Allied pursuit. York, his orderly, and Louis Alexandre Andrault de Langeron galloped through the burning village and soon spied a formation of cavalry. Believing it to be friendly, York rode up to the horsemen, announcing, "Here are my Hanoverians!" Recognizing that they were French, Langeron grabbed York's bridle and led him back to Marquion.[17]

In order to get his cavalry across the Agache, York sent some units south to cross at Sains-lès-Marquion. However, that crossing was difficult and time consuming.[11] Two French battalions that retreated from Thun-l'Évêque appeared and were driven into Marquion by the British cavalry. They would have been captured, but Kilmaine heard of their predicament and advanced a large force of cavalry and some artillery.[18] The eight British squadrons available became embroiled in a melee with Kilmaine's cavalry and the two French battalions escaped. The Allied operation only netted 3 guns and 150 prisoners. Unknown to the Allies, a portion of Kilmaine's army suffered a stampede that day. As the retreating column marched toward Arras, the leading troops, those farthest from the enemy, panicked. The rot spread and entire battalions shouted, sauve qui peut (every man for himself) and fled. The artillery park became separated from the rest of the army for 12 hours.[11] If Kilmaine had not blocked York's cavalry with his own cavalry, the day might have ended in a French disaster.[15]

Aftermath

According to Langeron, York returned to Bourlon where he got into an argument with Coburg's chief-of-staff Friedrich Wilhelm, Fürst zu Hohenlohe-Kirchberg, blaming him for the escape of the French.[11] The Austrians blamed York for the escape, even though Coburg had assigned Hohenlohe to York's column in order to oversee its movements. Pulteney wrote this criticism of the operation, "We were not in force to attack the enemy, the duke's [York's] column was a long way from support, and between ourselves we were not sorry to see them go off."[14] The Allies summoned the now isolated fortress of Cambrai to surrender, but its governor Nicolas Declaye refused, saying, "I do not know how to surrender, but I know well how to fight."[18]

Kilmaine redeployed his army behind the Scarpe with his right flank on Arras, his left flank on Douai, and his headquarters at Gavrelle. The advance guard under Joseph de Hédouville was on the south bank of the Scarpe, covering the army.[20] Kilmaine found out that he was removed from command on 14 August. The Committee of Public Safety was suspicious of him because he had English relatives. Kilmaine vowed that he was true to the French Republic and claimed that he would make a good cavalry commander. Nevertheless, his retreat from Caesar's Camp was regarded as criminal. Maximilien Robespierre and Louis Antoine de Saint-Just denounced Kilmaine, and on 23 December 1793 he was arrested. Kilmaine avoided the guillotine, was released after the fall of Robespierre, and served in Italy under Napoleon Bonaparte, who regarded him as a suitable commander for a detached corps.[21]

After the action, Coburg urged York to remain and help capture Cambrai or to make a new attack on the French army, but York had to follow orders from Henry Dundas of the British Home Office.[14] At this moment, the Allies had 118,000 troops opposite the gap in the French fortress line at Valenciennes. Phipps believed that the French were "at the mercy of the Allies" and that splitting their forces saved France from defeat. Yet, the British government desired to seize Dunkirk. The Prussians chose this moment to withdraw their 8,000-man contingent from Coburg and send it to Luxembourg City and Trier. Coburg remained and began the Siege of Le Quesnoy, which ended with a French surrender on 10 September 1793.[22] York assembled 37,000 troops at Marchiennes and marched northwest toward Dunkirk via Menen.[23] However, the Allied Siege of Dunkirk proved to be a complete failure.[24]

Notes

- Footnotes

- ↑ Cust did not specify which light dragoon or dragoon guard regiments were present. Fortescue listed the light dragoon regiments with the army (Fortescue, p. 49), but not the dragoon guards.

- Citations

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, p. 181.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, pp. 185–187.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, p. 57.

- 1 2 Phipps 2011, pp. 188–189.

- ↑ Smith 1998, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, pp. 192–193.

- 1 2 Fortescue 2016, p. 59.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, pp. 203–204.

- ↑ Smith 1998, pp. 50–51.

- 1 2 3 4 Phipps 2011, p. 206.

- 1 2 3 4 Cust 1859, p. 144.

- 1 2 Phipps 2011, p. 204.

- 1 2 3 4 Fortescue 2016, p. 60.

- 1 2 Phipps 2011, p. 207.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, pp. 204–205.

- 1 2 Phipps 2011, p. 205.

- 1 2 3 Cust 1859, p. 145.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, p. 49.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, pp. 206–207.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, pp. 208–210.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, pp. 213–214.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, p. 61.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, pp. 70–71.

References

- Cust, Edward (1859). "Annals of the Wars: 1783–1795". pp. 144–145. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- Fortescue, John W. (2016). The Hard-Earned Lesson: The British Army & the Campaigns in Flanders & the Netherlands Against the French: 1792–99. Leonaur. ISBN 978-1-78282-500-5.

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011). The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume I The Armée du Nord. USA: Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908692-24-5.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.