| Battle of Cynoscephalae | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Macedonian War | |||||||

A map showing the location of Cynoscephalae | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Roman Republic Aetolian League | Macedonia | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Titus Quinctius Flamininus Amynander of Athamania |

Philip V (king) Heracleides of Gyrton Athenagoras of Macedon Nicanor the Elephant | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

c. 26,000 21,600 infantry 1,300 cavalry 3,000 marines 20 war elephants[1][2][3] |

25,500 16,000 phalangites 2,000 light infantry 5,500 mercenaries and allies 2,000 cavalry[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 700 killed |

13,000 8,000 killed 5,000 captured | ||||||

The Battle of Cynoscephalae (Greek: Μάχη τῶν Κυνὸς Κεφαλῶν) was an encounter battle fought in Thessaly in 197 BC between the Roman army, led by Titus Quinctius Flamininus, and the Antigonid dynasty of Macedon, led by Philip V, during the Second Macedonian War. It was a decisive Roman victory and marked the end of the conflict.

Background

The First Macedonian War (started due to an alliance between Macedon and Carthage against the Romans during the Second Punic War in 215 BC) had ended in a stalemate; between the Roman alliance with Aetolia and the destruction of the Macedonian fleet early in the war, the Macedonians were unable to support Carthage and were forced into a defensive stance. A truce was signed between Macedonia and Rome in 205 BC leading to an uneasy peace. The Second Punic War would end not long after in 201 BC. Although Macedonia had limited effect in the Second Punic War, their alliance with Carthage would earn the ire of the Romans.[4]

In 202 BC, the Fifth Syrian War would break out, with the Macedonians allying with the Seleucids in a pact to carve up Asia Minor. Philip's moves towards the city states in Thrace, around the Dardanelles and later actions towards Rhodes and the Kingdom of Pergamum greatly disconcerted the two states. Although Rhodes and the Kingdom of Pergamum would later gain the upper hand against Philip, with a crushing defeat of his navy at the Battle of Chios,[5] they were still concerned enough about Macedon to send envoys to Rome to try and convince them to join the war. Rome in turn sent envoys to Greece to form an anti-Macedonian coalition, which Philip took as a sign of weakness from Rome due to the fact the Second Punic War had only just ended. When Philip failed to give up on further conquests in the region, the Roman Senate and Assembly declared war, beginning the Second Macedonian War.[6]

On 15 March 198 BC, new consuls took office, with command in Macedonia being handed to Titus Quinctius Flamininus. Flamininus, upon his arrival in Greece, would go on to have a meeting with Philip to discuss the terms of peace, demanding nothing less than the complete withdrawal of Macedonian forces from all of Greece outside of the Macedonian homeland. Philip would then storm out of the meeting, with Flamininus beginning his campaign.[4]

By the start of 197 BC, Philip had lost most of his earlier conquests and had been set back to Macedonia and parts of Thessaly.[7] In the spring of that year, Flamininus brought his army to Thessaly, with Philip marching his army south to meet him. The two initially camped nearby the city of Pherae, holding skirmishes there. However, Philip's army was in need of food and level ground in order to deploy his phalanx (something the terrain was unsuitable for at Pherae), so he began marching his army westward towards the small town of Scotussa for its grain stores. They marched on the northern side of the slopes while the Romans followed on the southern side, these slopes being the Cynoscephalae Hills.[4][8]

Armies

Romans

Flamininus had about 26,000 men, consisting of two full legions with the support of 6,000 infantry and 400 cavalry from the Aetolian League and an additional 1,200 men under Amynander of Athamania.[7] He also commanded war elephants from Numidia.[9] Reinforcements from Italy brought Flamininus an additional 6,000 infantry, 300 cavalry and 3,000 marines.[10]

Macedonians

Philip had about 25,500 men of which 16,000 were phalangites levied from across the kingdom consisting of wildly varying ages from young boys to aged veterans, due primarily to the perpetual wars creating a lack of manpower.[9][11] Alongside this, there were 2,000 peltasts (light infantry) with an additional 4,000 men from the Thracians and Trallians, 1,500 mercenaries and 2,000 cavalry.[12]

The Thessalian cavalry was led by Heracleides of Gyrton and the Macedonian cavalry by Leon. The mercenaries (except the Thracians) were commanded by Athenagoras of Macedon and the second infantry corps by Nicanor the Elephant.[13][14]

Battle

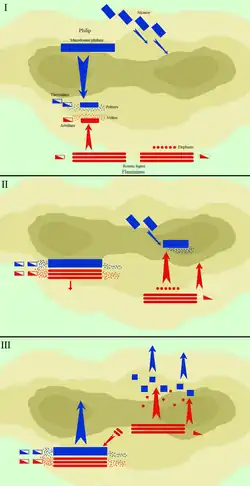

During the march there was a heavy rainstorm, and the morning after there was a fog over the hills and fields separating both camps. Despite fearing an ambush, Philip's force was in desperate need of supplies; thus Philip resumed his march, however his troops soon became confused and disoriented due to the heavy fog. For this reason, Philip decided to instead pitch camp but did still send out half his heavy infantry to search for food. To offset the inherent risk of this, Philip also sent his light infantry and half of his cavalry in order to take the Cynoscephalae Hills and locate the Roman force. Flamininus, likewise unaware of Philip's location, sent 1,000 light infantry and 300 cavalry to try and locate their forces, resulting in an engagement with Philip's troops on the hills.[4]

In the thick fog at the top of the hills, the light infantry of both forces ran into each other, with the limited visibility resulting in a confused battle of hand to hand combat as opposed to the usual hurling of javelins before the enemy could get too close. Then, the cavalry that both sides had sent up with their reconnaissance forces became involved in the fight, with the Romans slowly becoming overpowered due to the superiority in numbers of both infantry and cavalry that the Macedonian force had. As such, the Roman force soon requested aid from Flamininus.[4][7][9]

Flamininus sent an additional 2,000 light infantry and 500 cavalry up the slope to assist them, sending so few because of the fog still hanging over the battlefield, effectively blinding him to what was happening; he was unable to send the rest of his force until he could be sure as to how many Macedonians were involved and where they were.[4][7] Despite their limited numbers, these reinforcements gave the Romans the upper hand, with the Macedonians now being driven back to the peaks of the Cynoscephalae and away from level ground. Messengers were sent to Philip requesting reinforcements, however he realised that the entire Roman force could be waiting for him to attack. Additionally, half his heavy infantry had still not returned from foraging for food. As such, he didn't send any additional forces until the fog began to clear and the Macedonian situation became clear to him, now showing that only Roman light infantry and cavalry were involved. Philip sent one of his officers, Athenagoras, along with 1,500 mercenary heavy infantry and 1,500 heavy cavalry.[4] This forced the Romans into a retreat off the summit, however they were not completely pushed off the hills due to their Aetolian cavalry. The battle then developed into a stationary fight on the plains near the Roman camp.[4][7][9]

Philip received exaggerated reports of this retreat by the Roman reconnaissance force, believing that his troops had routed the entire Roman force.[4] Though reluctant to send his phalanx into the broken, hilly terrain, as a result of the glowing reports from his forces he ordered an assault by 8,000 phalangites and 4,000 peltasts. He then instructed Nicanor to form up the rest of the now returning phalangites and follow him as quickly as possible.[4][8]

The presence of such a force in front of his camp caused Flamininus to lead the rest of his force out of his camp, forming them into a battle line and placing his war elephants to the front of his right wing. The spaced organisation of the Roman maniple allowed the retreating Romans to escape the Macedonians, who in turn fell back at the sight of the Roman battle lines forming up.[4][9] Flamininus commanded from his left legion and advanced with it, leaving his right in reserve.[9]

Philip, now realising the reports were exaggerated, arrived just in time to see his forces retreating back up the hill. Knowing any attempt at a retreat would result in disaster, Philip rallied his cavalry and other retreating troops as they reached the top of the ridge, forming them up to the far right of his formation. He then formed the peltasts to the left of his cavalry, and his phalangites to the left of the peltasts, then forming a peltast line 16-men deep and a phalangite line 36-men deep. Unable to wait for Nicanor to arrive, Philip sent his right phalanx into the Roman left wing, driving them down the ridge, albeit at a slow pace.[4][8][9][15]

While this was going on, the Macedonian left led by Nicanor was arriving piecemeal at the top of the ridge. Upon seeing this disorganisation, Flamininus rode to his right wing and ordered them to attack, his elephants leading the way along with the rest of his forces, their Italian allies and 4,000 Greek infantry. Still in a column march, with others struggling to get up the hills, the war elephants smashed into the disorganised Macedonian left, scattering them and sending them back down the hill with the Romans in pursuit.[4][7][8][9]

As this pursuit was ongoing, an unnamed tribune (upon realising their position at the exposed rear of the Macedonian right wing) detached 20 maniples (approximately 2,500 infantry combined) and sent them into the rear of the Macedonian phalanx.[4][7][8][9][15] Being quickly cut down due to the inflexibility of the formation, the Macedonian phalanx disintegrated. Some were simply killed where they stood, others pointed their sarissas directly upwards in a sign of surrender that the Romans either ignored or failed to understand. Thus, the slaughter continued, only being stopped due to the intervention of Flamininus.[4]

Phillip, along with a small group of his cavalry, had pulled back to the summit for a better look at the battle, only to see the collapse of his right wing and the rout of his left. It was then that he fled the battle with his escort, returning to Macedonian territory.[4][7][9] Plutarch would later say;

Philip, however, got safely away, and for this the Aetolians were to blame, who fell to sacking and plundering the enemy's camp while the Romans were still pursuing, so that when the Romans came back to it they found nothing there.

— The Parallel Lives, The Life of Titus Flamininus, Volume X, p.345

Aftermath

According to Polybius and Livy, 8,000 Macedonians had been killed. Livy mentions that other sources claim 32,000 Macedonians were killed and even one writer who due to "boundless exaggeration" claims 40,000 but concludes that Polybius is the trustworthy source on this matter.[16] Flamininus also took 5,000 prisoners. The Romans only lost around 750 men in the battle.[4][7][8][9]

It is generally perceived that with the later Battle of Pydna, this defeat demonstrated the superiority of the Roman legion over the Macedonian phalanx. The phalanx, though very powerful head on, was not as flexible as the Roman manipular formation and thus unable to adapt to changing conditions on the battlefield or break away from an engagement if necessary.[4][9] This assertion has been challenged by some who point out that the Romans were only able to attain victory by taking advantage of the fact that the Macedonian left wing was not fully formed, although this is also given as evidence of the phalanx's unwieldy nature when compared to the legion.[7][9]

In any case, the result of the battle of Cynoscephalae was a fatal blow to the political aspirations of the Macedonian kingdom; Macedonia would never again be in a position to challenge Rome's geopolitical expansion. Although the peace that followed in 196 BC allowed Philip to keep his kingdom intact, Philip was forced to;[4][8][17][18]

- Relinquish his earlier conquests and return to the borders of the Macedonian homeland

- Remove all of his garrisons outside of Macedonia (in order to make those nations free and autonomous, to be done before the Isthmian Games of 196 BC)

- Pay an indemnity of 1,000 talents of silver to Rome (half of which was to be paid immediately, the other in 10 annual instalments of 50 talents)

- Give up all but 5-10 of his decked ships

- Only hold an army of 5,000 soldiers (which could contain no elephants)

- Not conduct war beyond the borders of Macedonia without the permission of the Roman Senate

Plutarch also stated that they took one of Philip's sons, Demetrius, as a hostage;

...and taking one of his sons, Demetrius, to serve as hostage, sent him off to Rome, thus providing in the best manner for the present and anticipating the future

— The Parallel Lives, The Life of Titus Flamininus, Volume X, p.347

However, 5 years later he was released to Philip due to the assistance given by Macedonia to Rome during the war against the Seleucids;

And apart from this money Philip owed his fine of a thousand talents.This fine, however, the Romans were afterwards persuaded to remit to Philip, and this was chiefly due to the efforts of Titus; they also made Philip their ally, and sent back his son whom they held as hostage.

— The Parallel Lives, The Life of Titus Flamininus, Volume X, p.363

At the Isthmian Games in 196 BC, Flamininus would announce that all Greek states previously controlled by Philip were now free and independent of his rule.[8]

References

- 1 2 Plutarch (100). "The Life of Titus Flamininus". The Parallel Lives. Loeb Classical Library.

- ↑ "Organization of the Roman Army: Manipular legion Organization of Legion". Penn State. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ↑ "Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 32". Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 History, Military (2018-12-07). "Cynoscephalae, 197 BC | The Past". the-past.com. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ↑ "Battle of Chios | Summary | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ↑ "Cynoscephalae (197 BCE) - Livius". www.livius.org. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Battle of Cynoscephalae, 197 B.C." www.historyofwar.org. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Battle of Cynoscephalae | Roman-Macedonian War, 197 BCE | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "Battle of Cynoscephalae (197 BC) | The Success of the Roman Republic and Empire". sites.psu.edu. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ↑ "Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 32, chapter 28". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ↑ "Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 33, chapter 4". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ↑ "Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 33, chapter 4". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ↑ "Perseus Under Philologic: Polyb. 18.22.3". anastrophe.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- ↑ "Polybius, Histories, book 18, The Battle of Cynoscephalae". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2023-10-27.

- 1 2 "Plutarch • Life of Flamininus". penelope.uchicago.edu. p. 345. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ↑ Titus Livius (1905). "33.10 The Second Macedonian War – Continued". The History of Rome. Vol. 5. J. M. Dent & Sons, Ltd., London. Archived from the original on 2021-08-20. Retrieved 2015-04-29.

- ↑ "Plutarch • Life of Flamininus". penelope.uchicago.edu. p. 347. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

- ↑ "Titus Livius (Livy), The History of Rome, Book 33, chapter 30". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2023-10-29.

Further reading

- Hammond, N. G. L. (1988). "The Campaign and Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BC". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 108: 60–82. doi:10.2307/632631.

- Polybius, Histories, XVIII. 19–27.