| Battle of Glières | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Second World War | |||||||

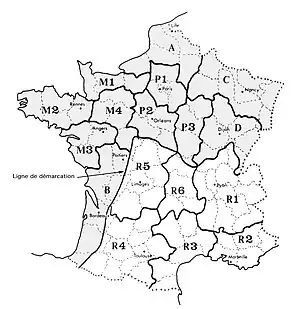

Geographic organization of the French Resistance showing the Haute-Savoie and Rhône-Alpes region in R1 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| circa 450 maquisards (including 56 Spanish fighters and 80 Francs-tireurs) |

over 1,400 Vichy policemen 700 militia (of the Franc-Gardes) 3,000 German soldiers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 140 killed or deported | 21 killed | ||||||

The Maquis des Glières was a Free French Resistance group, which fought against the 1940–1944 German occupation of France in World War II. The name is also given to the military conflict that opposed Resistance fighters to German, Vichy and Milice forces.[1][2]

Resistance

At the end of 1943, the French Resistance in the French Alps of Haute-Savoie needed arms. To find good drop zones to supply the Maquis with arms and sabotage equipment, a mission composed of Richard Harry Heslop from the Special Operations Executive and Captain Rosenthal from the Free French Forces was sent from London. The Glières Plateau, a high remote mountain table close to Lake Annecy, was chosen.

On 31 January 1944, Lieutenant Tom Morel, a Chasseur alpin from the 27th chasseurs alpins battalion (mountain light infantry) in Annecy, was commissioned to collect parachute drops from the Royal Air Force (RAF) with 100 men. Captain Rosenthal, the Free French representative, convinced the other staff members to regroup the majority of maquisards on the Glières Plateau, to establish a base to attack the Germans and carry out sabotage. Because the Allies doubted the value of the French Resistance, the French considered it a political necessity to show they were capable of undermining German military power in France.

Repression

In January 1944, a state of siege was declared in Haute-Savoie. Anyone found carrying arms or assisting the Maquis was subject to immediate court martial and execution. Hunted by the Vichy police and badly supplied, most of the maquisards gathered on the Glières Plateau to set up their base of operations. Soon after, 100 French communist resistants and about 50 Spanish lumberjacks joined forces with them in taking refuge and getting weapons. From 13 February, the 450 maquisards, under the command of officers from the 27e bataillon de chasseurs alpins, were besieged by 2,000 French militia and police. Although they suffered from starvation and freezing conditions, they collected three parachute drops consisting of about 300 containers packed with explosives and small arms, including Sten sub-machine guns, Lee–Enfield rifles, Bren light machine guns and Mills bombs (hand grenades).

On the night of 9/10 March, the commander-in-chief, Lt. Tom Morel was killed in a skirmish with the Vichy forces. On 12 March, after the largest Allied parachute drop, the Germans started to bomb the area with ground attack aircraft. The Milice (French paramilitary police) staged several attacks which failed. On 23 March, three battalions from the German 157th Reserve Division and two Order Police battalions, composed of more than 4,000 men, with heavy machine guns, 80 mm mortars, 75 mm mountain guns, 150 mm howitzers and armoured cars, concentrated in Haute-Savoie.

Retreat

On 26 March 1944, after another air raid and shelling, the Germans took the offensive. They split their attacking parties into three groups (Kampfgruppen) with an objective for each group. Reconnaissance was carried out by ski patrols dressed in white camouflage. One of the patrols from a Gebirgsjäger (mountain troops) platoon, made an attack on the main exit from the plateau and captured an advanced post in the rear. Sustaining the attack from about fifty German soldiers, eighteen maquisards fought and resisted into the night but were outnumbered and overwhelmed, though most of them escaped under cover of darkness. Captain Anjot ordered the Glières battalion to retreat. In the days that followed, he and almost all his officers, as well as 120 maquisards, were found dead. They had been killed in battle or, if taken prisoner, had been tortured, shot or deported. The Germans considered the maquisards terrorists.

The region of Savoie had suffered badly, but the defeat was turned into a propaganda victory and gave a boost to the French Resistance in the spring of 1944.

.svg.png.webp)