| Battle of Henderson's Hill | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the American Civil War | |||||||

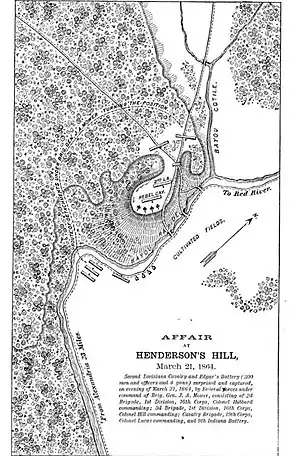

Map shows Henderson's Hill (top) and its relation to Alexandria. The town of Cotile is now named Boyce. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Joseph A. Mower | William G. Vincent | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| negligible | 222–250 men, 4 guns | ||||||

The Battle of Henderson's Hill or Bayou Rapides (March 21, 1864) saw a reinforced Union Army division led by Brigadier General Joseph A. Mower opposed by a regiment of Confederate Army cavalry and attached artillery under Colonel William G. Vincent. That evening, during a rainstorm, Mower sent one infantry brigade on a circuitous march to gain the rear of Vincent's command. The brigade's subsequent attack surprised and captured most of the Confederates. Mower could not exploit his minor victory because the arrival of additional Federal army and naval units was delayed. This clash occurred during the Red River campaign of the American Civil War which saw Major General Nathaniel P. Banks' Union army try to seize Shreveport, Louisiana, from its Confederate defenders led by Lieutenant General Richard Taylor.

Background

Plan

Worried about Maximilian's Second French intervention in Mexico, President Abraham Lincoln desired military operations to establish United States control over some part of Texas. Over the opposition of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, and Major Generals William T. Sherman and Nathaniel P. Banks, Lincoln and Major General Henry Halleck drew up a plan to use the Red River as an invasion corridor. As commander of the Department of the Gulf, Banks was instructed to coordinate operations with Major General Frederick Steele in Arkansas and Sherman. The plan that emerged was for Banks with 17,000 troops to move up Bayou Teche and link up at Alexandria, Louisiana, on March 17, with 10,000 troops borrowed from Sherman's Military Division of the Mississippi. From there, the combined force would ascend the Red River toward Shreveport. Meanwhile, Steele with 15,000 was supposed to move south from Little Rock, Arkansas, and rendezvous with Banks at either Shreveport, Alexandria, or Natchitoches, Louisiana. Steele's column got underway so late that it fought a separate series of actions.[1]

Forces

General Edmund Kirby Smith's Trans-Mississippi Department had 30,000 Confederate soldiers evenly distributed in three bodies. These were led by Richard Taylor in Louisiana, Major General John B. Magruder on the Texas coast, and Lieutenant General Theophilus H. Holmes near Camden, Arkansas. Taylor had Major General John George Walker's infantry division (3 brigades) at Marksville, Louisiana and Brigadier General Alfred Mouton's infantry division (2 brigades) on the Red River below Alexandria. Vincent's 2nd Louisiana Cavalry Regiment was posted at Vermilionville on Bayou Teche, except for three companies with Walker.[1] Brigadier General Thomas Green's cavalry was coming from Texas and would not reinforce Taylor until the first week of April.[2]

On March 10, 1864, the 10,000-man force contributed by Sherman departed from Vicksburg, Mississippi in river transports. It was led by Brigadier General A. J. Smith and accompanied by 13 ironclads and 7 light-draft gunboats commanded by Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter.[1] There were Mower's two divisions from the XVI Corps and one 1,700-man division from the XVII Corps under Brigadier General T. Kilby Smith. Banks' force included Brigadier General Thomas E. G. Ransom's two divisions from the XIII Corps (4,800 men), Major General William B. Franklin's two divisions from the XIX Corps (10,500 men), and a cavalry division led by Brigadier General Albert Lindley Lee (4,600 men). Banks also had a 1,500-strong brigade of African-American soldiers led by Colonel W. H. Dickey[3] that was made up of the 73rd US, 75th US, 84th US, and 92nd US Colored Infantry Regiments.[2]

Operations

Porter's gunboat fleet entered the mouth of the Red River on March 12, 1864, and landed A. J. Smith's corps at Simmesport, Louisiana, the following day. Walker's division, which was covering the area between Simmesport and Opelousas, immediately withdrew behind Bayou Boeuf where it could defend Alexandria. On March 14, in the Battle of Fort De Russy, A. J. Smith's troops assaulted and captured the fort. For a cost of 34 Union casualties, 260 Confederate prisoners, 8 heavy cannon, and 2 field guns fell into Federal hands. At the same time, Porter's fleet broke through obstructions in the river and steamed upstream, reaching Alexandria on March 15. The next day, Alexandria was occupied by Kilby Smith's division which disembarked from river transports. Taylor withdrew Walker's division and recalled Mouton's division from north of the Red River. A. J. Smith followed and his forces were established in Alexandria by March 18.[4] On March 18, Taylor concentrated the divisions of Walker and Mouton at Carroll Jones' plantation which was located 36 mi (58 km) northwest of Alexandria.[5] Taylor's force numbered 5,300 infantry, 500 cavalry, and 300 artillery. Meanwhile, Banks missed the March 17 date for the rendezvous with A. J. Smith.[6] Banks' tardy column, which was commanded by Franklin, moved north along Bayou Teche via Opelousas, and was delayed by bad weather. Lee's cavalry division reached Alexandria on March 19, but Franklin's infantry and artillery did not arrive until March 25–26. However, the water level in the Red River was still too low, and it would not be until April 3 that Porter's 13 gunboats and 30 river transports were able to get upstream past the rapids at Alexandria.[7]

Battle

Vincent's 2nd Louisiana Cavalry joined Taylor's force on March 19. Taylor reinforced Vincent's regiment with Captain William Edgar's 1st Texas Field Battery and sent it toward Alexandria, where it skirmished with the Federals for two days.[2] A. J. Smith ordered Mower to take his own infantry division and Colonel Thomas J. Lucas' cavalry brigade to probe to the north.[6] Mower's force included the infantry brigades of Colonels Sylvester G. Hill and Lucius Frederick Hubbard, plus the 9th Indiana Battery.[2] On March 21, Mower's task force marched north along Bayou Rapides, with Lucas' cavalry pressing Vincent back for 7 mi (11.3 km) to the southern edge of Henderson's Hill. By the time Mower's infantry arrived, Vincent's troops formed a defensive line, supported by Edgar's artillery. Vincent asked Taylor to send reinforcements.[6]

Mower ordered Lucas to occupy the Confederates' attention from the front. At the same time, the Union leader sent Hill's brigade on a march around Vincent's right flank to strike the Confederates from the rear.[6] Hill's brigade consisted of the 33rd Missouri and 35th Iowa Infantry Regiments.[8] After a difficult 8 mi (12.9 km) march during a cold rain and hailstorm, Hill's troops got into position at dusk. They advanced on Vincent's position from the rear with fixed bayonets, overrunning the picket line, and sweeping into the Confederate camp by surprise, opposed by only a "few pistol-shots". Contributing to the surprise was the Confederates' belief that Hill's troops were reinforcements sent by Taylor.[6]

Walter Coffey asserted that the Federals captured 222 men, 4 cannons, 4 caissons, 32 artillery horses, 126 cavalry horses, 92 small arms, and 1 ambulance. Vincent and a few others escaped capture.[6] Historian Mark M. Boatner III and Battles and Leaders stated that the Federals captured 250 men and 4 guns.[2][5] A. J. Smith's official report stated that his troops seized two M1841 12-pounder howitzers, two M1841 6-pounder field guns, and four caissons. It claimed that the captured included 4 officers and 45 men from Edgar's Texas Battery, 15 officers and 192 men from the 2nd Louisiana Cavalry, 2 men from the 16th Texas Cavalry, and 3 officers from various commands, for a total of 22 officers and 239 men captured.[9]

Taylor blamed the disaster on "the treachery of citizens" who revealed to the Union troops "a road unknown to my best guides".[6] An enlisted man in Walker's division explained the surprise as follows. He wrote that Vincent's pickets were posted too far apart, allowing a "Jayhawker" (Louisiana Unionist) to pose as a picket and obtain the countersign from a courier arriving from Taylor. Having gotten this information, the Unionist went to the Federal camp and divulged the countersign. This was the reason why the Federals were able to capture Vincent's pickets without an alarm being given.[10] Taylor complained that the loss of his cavalry left him without the ability to reconnoiter. Nevertheless, the Union army failed to follow up its victory. Mower returned to Alexandria to await the arrival of Banks' infantry and artillery, while Taylor's force fell back to Natchitoches and Mansfield.[6] The Battle of Mansfield on April 8 proved to be the limit of the Union army's advance.[11]

Notes

- 1 2 3 Boatner 1959, p. 685.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Boatner 1959, p. 686.

- ↑ Battles & Leaders 1987, pp. 349–351.

- ↑ Battles & Leaders 1987, p. 349.

- 1 2 Battles & Leaders 1987, p. 351.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Coffey 2019.

- ↑ Battles & Leaders 1987, pp. 349–350.

- ↑ Battles & Leaders 1987, p. 367.

- ↑ Official Records 1891, p. 314.

- ↑ Blessington 1875, p. 178.

- ↑ Boatner 1959, p. 715.

References

- Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Vol. 4. Secaucus, N.J.: Castle. 1987 [1883]. ISBN 0-89009-572-8.

- Boatner, Mark M. III (1959). The Civil War Dictionary. New York, N.Y.: David McKay Company Inc. ISBN 0-679-50013-8.

- Blessington, Joseph P. (1875). "The Campaigns of Walker's Texas Division". New York, N.Y.: Lange, Little & Co. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- Coffey, Walter (2019). "Red River: The Henderson's Hill Engagement". The Civil War Months. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- Official Records (1891). "A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies: Volume XXXIV Part I". Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 314. Retrieved January 11, 2023.