| Roman Civil War of 456 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Fall of the Western Roman Empire | |||||||

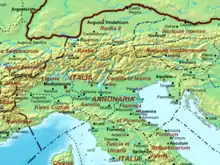

Northern Italy | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Formal authority | Insurgents | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Avitus Remistus Messianus |

Majorianus Ricimer | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 5,000 - 10,000 | 15,000[1] | ||||||

The Roman Civil War of 456 was a military conflict in the 2nd half of 456 in which the generals Majorianus and Ricimer revolted against the West Roman Emperor Avitus. The war ended with a victory by the insurgents. Avitus was deposed as emperor and died shortly thereafter in mysterious circumstances.

Sources

For the events in the Western Roman Empire in the period after the death of Valentinian III (455), historians have only scarce chronicles and fragments from historiography at their disposal. In addition, the Panegyric of Sidonius Apollinaris about Avitus and his letters provides important information about this phase of Roman rule in the west.

Background

Among historians, there is a consensus that Avitus' reign was not strongly rooted at the beginning in 455. The successor of Emperor Maximus was rather dependent on the support of all major players in the Western Roman Empire about that time. That support was indispensable to gain sufficient control over both the civil institutions, the Senate and the East Roman Emperor Marcian, as well as those of the army and its commanders (the Generals Majorian and Ricimer). Moreover, his relationship with the eastern part of the empire was not optimal. In contrast, his relationship with the Visigothic king Theodoric II was excellent.[2]

As a reason for Avitus' weak position, he had been put forward by the Gallic senators with the support of Theodoric as a successor to Maximus, while the core of the power of the Western Empire was still in Italy where he was considered an outsider by the Senate in Rome. According to Sidonius Appolaris, the generals Majorianus and Ricimer himself were also interested in the throne and had already had plans in that direction after the death of Emperor Valentinianus.[3] Initially they supported Avitus' reign, but dropped him when he got into trouble.

At the time of Avitus' reign, there were two major domestic conflicts. In northern Spain the Sueves were on a warpath and since the Sack of Rome the Romans were at war with the Vandals of Geiseric. The Visigothic army, together with the Burgundy campaigned for Avitus in Spain to restore power there.[4] In the Mediterranean, the Roman army under Ricimer took action against the Vandals.[5] Ricimer achieved some successes, but at sea Geiseric proved difficult to beat. The Vandals blocked the port of Rome, causing famine to break out in the capital - which for its food supply depended on grain from Africa.

The Civil War

Prelude

Halfway through 456 during the food blockade, Avitus stayed in Rome where he was confronted by hungry and dissatisfied residents. The fact that he belonged to the Gallic aristocracy and had appointed several Gauls to high posts worked to his disadvantage. Some senatorial circles blamed him for the famine. In addition, he also had problems with his army because he did not have enough cash to pay their wages.

At this stage, Ricimer and Majorianus seriously began plans to depose Avitus. Ricimer had gained prestige after his victories and Majorian had a strong following among the troops previously loyal to Aetius.[6]

The Rebellion in Rome and Avitus' flight to Gaul

Avitus, who was never loved much by the people, lost his support in the Senate in the course of 456. For Ricimer and Majorianus this was the perfect moment to draw power to them and revolted. The emperor had to flee because a large part of the imperial army sided with the insurgents. He fled to Gaul to gather reinforcements there. When Avitus arrived in Arles he scraped some troops together, but had to do it without the support of the Visigothic King Theodoric who campaigned in Spain.[7]

The assassination of Remistus

The first action in the revolt of Ricimer and Majorian was the assassination of the commander-in-chief magister militum Remistus, who had been commissioned by Avitus to preserve the imperial seat Ravenna for him. In September 456, Ricimer went with an army to Ravenna and surprised the magister militum near the city. The sources do not clearly indicate under what circumstances the attack took place. The result of the attack did, Remistus was killed.[8] Then the troops of Ricimer and Majorianus moved north to intercept the reinforcements Avitus had gathered in Arles.

The battle of Piacenza

Avitus appointed a new commander-in-chief Messianus to succeed Remistus and prepared for the confrontation with Ricimer and Majorian. With the army he gathered in Gaul, he returned to Italy in early October. Near (Piacenza) he encountered the army of Recimer and Majorian where there was a battle between the Roman armies. Avitus was clearly the lesser, he lacked the support of the Gothic foederati and possibly could only have gathered part of the established Gallic army in that short time. The insurgents, on the other hand, had most of the Italian comitanses. The emperor attacked the much strenger army led by Ricimer with his troops on October 17 or 18, and after a major massacre among his men, including Messianus, Avitus fled and took refuge in the city. In the immediate aftermath, Ricimer saved his life, but forced him to become bishop of Piacenza. As for his death shortly after, the sources are vague or contradictory; it is enough to say that this was very convenient for Ricimer and Majorian.

Aftermath and consequences

After the deposition and death of Avitus, the Gallo-Roman aristocracy revolted, turning to the Burgundy and Visigothic foederati for support.[9] When Theodoric and Gundioc reached the message about the impeachment of the emperor and the revolt in Gaul, Theodoric left the command to his generals Suneric and Cyril and returned to Toulouse, while Gundioc with his entire army returned to the mountains of Sapaudia.[10] Taking advantage of the confusing state, Theodoric saw opportunities to establish his own state on Roman soil. In the course of 457 he pushed the treaty with the Romans on the side with which the Goth War began.

The emperor Leo I , recently appointed to the east, who was now also emperor of the west until he had appointed a successor, was initially not inclined to cooperate with the rebellious generals. Eventually, the extremely unstable situation in the west asked for a solution that left his ears hanging on the two generals who made the service in Italy.[11]

Leo appointed Ricimer as patricius e magister militum commander-in-chief with the title of Patrician and Majorian as magister militum, making Majorian the subordinate of Ricimer.[12] Majorianus then forced Leo, with the support of the Senate, to appoint him as Caesar on April 1, 457. When he hesitated to acknowledge him, Majorian declared himself Emperor of the West on December 28, 457, with the support of the Senate and the army.

Primary sources

- Hydatius, Chronicles 169-174

- Sidonius Apollinaris, panegyriek and letters

- John of Antioch, Historia cronike

- Gregory of Tours, Historia Francorum

- Priscus, fragments

Bibliography

- O'Flynn, John Michael (1983), Generalissimos of the Western Roman Empire, The University of Alberta Press, ISBN 0888640315

- Hodgkin, Thomas (2001), The Barbarian Invasions of the Roman Empire, London: The Folio Society

- Heather, Peter (2006), The Fall of the Roman Empire, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195325416

References

- ↑ based on the troops assignment in the Notitia dignitatum

- ↑ Sidonius Apollinaris, Carmina 7, 495 ff

- ↑ O'Flynn 1983, p. 105.

- ↑ Hydatius, Chronicles 172-175, in: MGH AA 11, p. 28v.

- ↑ Hydatius, 176, s.a. 456; Priscus, fragment 24; Sidonius Apollinaris, Carmina, ii, 367

- ↑ O'Flynn 1983, p. 106.

- ↑ Hodgkin 2001, p. 395.

- ↑ Fasti vindobonenses priores, 579; Auctarium Prosperi Havniense, 1

- ↑ Sidonius Apollinaris, Letters I.11.6.

- ↑ Consularia Italica, Auctarium Prosperi, 457 years. C

- ↑ Heather 2006, p. 259.

- ↑ Fasti vindobonenses priores, 583.