| Skirmish at Top Malo House | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Falklands War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 19 | 13 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3 wounded |

| ||||||

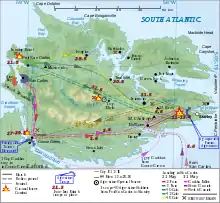

Location within Falkland Islands | |||||||

The Skirmish at Top Malo House took place on 31 May 1982 during the Falklands War between Argentine special forces from 602 Commando Company and the British Royal Marines of the Mountain and Arctic Warfare Cadre (M&AWC). Top Malo House was the only planned daylight action of the war, although it was intended to take place in darkness. The Argentine commandos were part of an attempt to establish a screen of observation posts. A section that occupied Top Malo House was sighted by a British observation post of the Mountain and Arctic Warfare Cadre that was screening the British breakout from the lodgement around San Carlos. The action at Top Malo House was one of a series of mishaps and misfortunes that afflicted the Argentine effort.

Background

Tensions between Britain and Argentina over a disputed territory the British called Falkland Islands and the Argentinians called Islas Malvinas escalated after Argentinian scrap metal merchants and Argentina Marines raised the Argentine flag over South Georgia Island on 19 March 1982.[1] On 2 April, Argentine forces occupied the Falkland Islands.[2] The British government sent a task force to recapture the islands,[3] and British forces landed in the Falklands in the vicinity of Port San Carlos on 21 May.[4]

Geography

.jpg.webp)

The geography of the Falkland Islands is characterised by open grasslands and heather. There are no native trees. The wind blows constantly, and the weather can change suddenly. A feature of the landscape is stone runs, fields of broken boulders. Outside the town of Stanley, the islands were dotted with small settlements, where farmers raised sheep. Fences were common. There were vehicle tracks around the settlements, but no roads between them. Cross-country movement by vehicle involved avoiding stone runs and peat bogs. The settlements were connected by light aircraft, and each had a landing strip. Items too heavy to move by air were shipped by water, using coastal shipping.[5]

Prelude

Argentine

The Argentinian Army did not maintain standing special forces units, but formed them from individuals with commando training when the need arose.[6] The Argentine 602 Commando Company was formed from fifty-four commando-trained soldiers on 21 May 1982 and flew to the Falklands in a Lockheed C-130 Hercules on 27 May.[7][8] Two days later, a thirteen-man patrol from 602 Commando Company set out from Stanley with orders to establish an observation post on Bluff Cove Peak.[9] This was part of a larger operation planned by the Argentine commander in the Falklands, Brigade General Mario Benjamín Menéndez, to establish a screen of observation posts in front of his defensive positions in the Stanley area manned by special forces.[10] This screen would strike at the British line of communications and capture British soldiers. An observation post would be established on Mount Estancia by 601 Commando Company, on Mount Kent by twelve men of 602 Commando Company and sixty-five from 601 National Gendarmerie Company, and on Mount Simon and Bluff Cove Peak by two sections of 602 Commando Company.[8]

The 602 Commando Company's 1st Assault Section of thirteen soldiers earmarked for Mount Simon was led by Captain José Arnobio Vercesi, and included Lieutenants Ernesto Espinosa and Daniel Martínez; First Lieutenants Juan José Gatti, Luis Alberto Brun and Horacio Losito; First Sergeants Mateo Sbert, Humberto Omar Medina, Miguel Angel Castillo, Faustino Pedrozo (medic, not member of 602 commando) and Juan Carlos Helguero (scout, member of 601 commando); Sergeant Carlos Bruno Delgadillo and Corporal Raúl Valdivieso.[11] The section took off from the Stanley racecourse in a Bell 212 helicopter and an Agusta 109 at 17:15 on 29 May.[9] Soon after they departed, the weather closed in and a helicopter carrying a patrol from 601 National Gendarmerie Company crashed, killing many of those on board.[9] The fly-out of the rest of the special forces was postponed until the following day.[12]

Vercesi and four of his men disembarked from the Agusta 109 in the vicinity of Mount Simon. The eight men from the Bell 212 failed to make the rendezvous, but Vercesi pressed on with the mission without them. His group established an observation post near the summit of Mount Simon, where they observed British air activity, and were joined by the missing eight men.[9] They remained on Mount Simon through the night, during which it snowed heavily. In the morning Sbert, the patrol radio operator, tried to get a message through that there was a British air corridor from San Carlos to Mount Kent but although his radio could receive it could not transmit. He managed to get one brief message through before radio contact was lost and never re-established.[11]

There was no point in manning an observation post without the means to report back, so Vercesi decided to make for Fitzroy, where an engineer detachment working on a bridge had a working radio set. Peat and stone runs slowed their movement. There was drizzling rain and intermittent snow, and they had to cross the Malo River, a fast-flowing stream swollen to waist-height with icy rainwater. Brun and Helguero had Antarctic experience, and they advised Vercesi to seek shelter. He therefore headed to nearby Top Malo House, a nearby corrugated iron structure with a wooden frame. They made a tactical approach to the building, but no British troops were present, so they moved in to take shelter.[11][13]

British

The Mountain and Arctic Warfare Cadre was a unit of the Royal Marines that trained marines in rock climbing and cliff assault techniques. This was conducted through the ML1 and ML2 mountain leader training courses for officers and non-commissioned officers (NCOs).[14] At the time the conflict in the Falkland Islands broke out in March 1982, ML1 and ML2 courses had recently been completed, with a curriculum that aimed to prepare graduates to fit into a brigade patrol troop.[15] The Mountain and Arctic Warfare Cadre formed a 36-man patrol troop under the command of Rod Boswell from the training staff and recently-graduated students. It consisted of a four-man headquarters and eight four-man sections. Each section included a signaller who had completed the special forces signal course, and a marine armed with an M79 grenade launcher. All personnel were officers or NCOs.[16] The Mountain and Arctic Warfare Cadre departed the UK on the stores ship RFA Resource on 5 April,[17] and arrived in the Falkland Islands on the landing ship RFA Sir Tristram on 21 May 1982.[18]

On 28 May, the Mountain and Arctic Warfare Cadre deployed four of its sections in the vicinity of Top Malo House to screen the breakout of 3 Commando Brigade from the lodgement at San Carlos. They had been landed in the rear of the 3rd Battalion, Parachute Regiment (3 Para), and had joined elements of that unit in its march towards Teal Inlet. About 2 km (1.2 mi) south of Teal Inlet they had peeled off from 3 Para's column and headed south, where they had established four observation posts. Lieutenant Fraser Haddow's 1 Section established its post on the south west ridge of Evelyn Hill overlooking the Malo River, and on 30 May it spotted the Argentinian patrol moving towards Top Malo House.[19] At first Haddow thought that his observation post had been spotted and the Argentine commandos were there to attack him. When this did not occur he realised that this was not the case, and radioed back to Mountain and Arctic Warfare Cadre headquarters with a request for an air strike on Top Malo House.[20]

When he received this message, Boswell went to 3 Commando Brigade headquarters. An air strike could not be carried out immediately, because a Harrier GR.3 had been lost that day in an air raid on Stanley. Procedures called for Harriers to operate in pairs, so another aircraft had to be readied, but it would not be available until morning. Nor could artillery be used; Top Malo House lay 48 km (30 mi) from the gun positions at San Carlos and was out of range. The guns were not scheduled to commence displacing forward to Teal Inlet until late the next day, and even then they would be at extreme range, 10 km (6.2 mi) from Top Malo House. Boswell then proposed a dawn raid on Top Malo House by the Mountain and Arctic Warfare Cadre. The brigade commander, Brigadier Julian Thompson, approved this operation.[20][21]

Boswell elected to take his headquarters and the four sections (5, 6, 7 and 8) at San Carlos, leaving only Colour Sergeant Bill Wright behind in San Carlos. This gave him a troop of 19 men. His plan was to take off from San Carlos at 06:00 on 31 May and land in pre-dawn darkness at 06:30. Sunrise was about 07:00. Aerial photographs were studied and a model of Top Malo House and its vicinity was constructed.[21] A stream junction about 2 km south west of Top Malo House was selected as the landing zone.[22] An "O Group", a formal process by which a commander informs his subordinates of the tasks they must perform in order to carry out a mission,[23] was held at 20:00 on 30 May, allowing the men to get a good night's sleep.[21]

Battle

The Mountain and Arctic Warfare Cadre troop arrived at the departure site at around 04:30. After watching several helicopters land and take off without them, Boswell boarded the next helicopter to land to speak to the pilot. This turned out to be Lieutenant Commander Simon Thornewill, the commanding officer of 846 Naval Air Squadron. Boswell explained what his mission was, and Thornewill detailed one of his helicopters that was waiting to land to take them. He then took off, the next helicopter, a Westland Sea King piloted by Lieutenant John Miller, came in to land. Boswell briefed Miller on the mission, and the Mountain and Arctic Warfare troop loaded themselves and their equipment onto the helicopter. Boswell was the last to board. He loaded the last five or six bergens (backpacks) and climbed on top of a pile of them, with his feet against the top of the door, which remained open throughout the flight. The overloaded helicopter took off and, after a 48 kilometre flight at low-level lasting about twenty minutes, deposited the troop at the designated stream junction.[24][25]

The bergens were dumped at the landing site. Boswell divided his troop into two groups: a seven-man fire group under Lieutenant Callum Murray, with Sergeant Mac MacLean and Corporals Matt Barnacle, Nigel Devenish, Steve Groves, Steve Nicoll and Bob Sharp; and an assault group led by himself with Colour Sergeant Phil Montgomery, Sergeants Terry Doyle, John Rowe, Chris Stone and Derek Wilson, and Corporals Tony Boyle, Keith Blackmore, Tim Holleran, Sam Healey, Ray Sey and Jim McGregor. The troop followed the stream for about 1.5 kilometres (1 mile), then crossed a small saddle before following another stream for 600 metres until they reached the fence line. The troop then split into its two groups: the fire group continued along the fence line until they found a suitable firing position, while the assault group followed the stream, rounding a small hill to approach Top Malo House without being observed. A peat cutting provided a concealed jumping off point for the assault. There was a significant risk of compromise as it was now daylight and the team was wearing dark camouflage uniforms that stood out against the snow, leading to the likelihood of visual detection by sentries.[25][26] Unbeknown to the British, the Argentines had heard the helicopter.[27]

Boswell ordered his men to fix bayonets and commenced the engagement by firing a green flare, the signal for the fire group to launch a salvo of four rockets from 66mm Light Anti-tank Weapons (LAWs) at Top Malo House. At around the same time Losito, who was second in command of the Argentine patrol, says that Espinosa (who was standing sentry) raised the alarm and opened fire on the assaulting British troops. Espinosa was seen by Groves, the troop sniper, who was sighting his weapon at the top floor window Espinosa was looking out. Groves fired at Espinosa, who disappeared from view. The first salvo of four LAW rockets all missed, but a second salvo of three all struck the building, which burst into flames.[28][26]

Boswell and his group charged forward, but halted after running about 50 metres towards the house. Two more LAW rockets were fired, then they charged forward again. The Argentinians ran from the house, taking cover in a stream bed about 200 metres away, firing as they ran. Espinosa on the top floor was killed by a 66 mm rocket while Sbert was shot dead as he gave covering fire for the remaining Argentines as they exited the single door. As the British assault group moved forward, smoke from the burning building screened them from accurate fire by the Argentine commandos in the stream bed.[29][30]

The firefight went on for about 45 minutes.[31] With ammunition running low and with seven members of his patrol wounded, Vercesi surrendered.[11][26]

Aftermath

The raid on Top Malo House was the only planned daylight action of the Falklands War.[32] Two Argentines (Espinosa and Sbert) were killed, seven were wounded and five were taken prisoner.[10][33][lower-alpha 1] Three members of the Mountain and Arctic Warfare Cadre (Doyle, Groves and Stone) had also been wounded.[10] McLean was injured in the hand when a round hit the 66mm LAW he was about to fire.[12] After the battle Boswell's comment to Vercesi was: "Never in a house".[35]

Top Malo House was completely destroyed. The small building nearby was found to contain only the carcasses of butchered sheep. An outhouse about 40 metres from the main house was secured by McGregor, who fired a magazine into it.[36] Soon afterwards, a four-man patrol waving a British flag was sighted. This was 1 Section; they had observed the fight and decided to join in.[37] Boswell radioed back to San Carlos with a request for helicopters to evacuate his wounded and retrieve his troop. This received no response, so he contacted Wright, who went to 3 Commando Brigade headquarters with his request. The three British and seven Argentine wounded were flown to the field hospital at Ajax Bay, escorted by three unwounded members of the Mountain and Arctic Warfare Cadre. The prisoners and the other Mountain and Arctic Warfare Cadre members were flown with their bergens to Teal Inlet, where the prisoners were handed over for interrogation.[36]

Espinosa and Sbert were posthumously awarded Argentina's highest decoration, the Argentine Nation to the Heroic Valour in Combat Cross, for this action.[7][38][39] Six other members of the Argentine patrol received gallantry awards. On the British side, Chris Stone was mentioned in despatches, and Tim Holleran received a Commander in Chief's commendation.[32][40]

According to Boswell, the assault had been witnessed by two other sections from 602 Commando Company, which surrendered to the 3rd Battalion The Parachute Regiment (3 PARA) and 45 Commando (45 CDO) the next day, and 602 Commando Company virtually ceased to exist.[36] The Argentines claim that no Argentine special forces surrendered to 3 PARA or 45 CDO and that the 2nd Assault Section (under Captain Tomás Victor Fernández) and 3rd Assault Section (under Captain Andrés Antonio Ferrero) along with the Headquarters and Support Section (under Captain Eduardo Villarruel) from 602 Commando Company continued operating aggressively against British patrols in the Murrell River area for another week and a half.[41] The Argentines also claim 602 Commando Company tied up British forces operating ahead of 3 Commando Brigade long enough to allow First Lieutenant Darío Horacio Blanco and his platoon of sappers from the 601st Combat Engineer Battalion to blow up part of the Bluff Cove and Fitzroy Settlements bridge unmolested on 2 June.[42][43]

The action at Top Malo House was part of a series of mishaps and misfortunes that beset the effort to create a special forces screen. Of the 170 personnel that were supposed to take part, only fifty were deployed, and of these thirty-two became casualties. The remaining special forces units were employed to protect installations around Stanley from raids, with 601 Commando Company guarding the heliport at Stanley Racecourse, and took little part in the upcoming battles around Stanley.[44] The loss of the screen meant that the northern prong of the British advance by the 3rd Commando Brigade was not under Argentine observation.[45]

Footnotes

- ↑ Argentine sources give thirteen men in the 602 Commando Company patrol (but not every are members of 602 Commando), see list in Prelude [11] but 1 Section of the Mountain and Arctic Cadre reported seventeen (perhaps a double counting between total patrol and non member of the 602 commando).[34] According to Boswell, there were also two warrant officers in a Blowpipe missile team and a two-man medical detachment present (in fact certainly Pedrozo and probably Helguero), which were not part of 602 Commando Company.[34] The official figure gives the two known dead plus the seven wounded and five prisoners, making fourteen (perhaps a double counting between wounded and prisoner).[10]

Notes

- ↑ Brown 1987, pp. 50–52.

- ↑ Freedman 2005, pp. 4–11.

- ↑ Freedman 2005, p. 16.

- ↑ Thompson 1985, pp. 55–60.

- ↑ Delves 2018, pp. 132–133.

- ↑ Van der Bijl 2020, p. 77.

- 1 2 "Héroes de Malvinas, Héroes de la Patria: Sargento Primero Mateo Sbert". www.argentina.gob.ar. 30 May 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- 1 2 Van der Bijl 1999, p. 144.

- 1 2 3 4 Boswell 2021, pp. 78–79.

- 1 2 3 4 Freedman 2005, p. 587.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Borda Bettolli, Carlos (3 June 2021). "El Ejército Argentino conmemoró el 39° aniversario del combate de Top Malo House" [The Argentine Army Commemorates the 39th Anniversary of the Action at Top Malo House]. www.zona-militar.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- 1 2 Van der Bijl 1999, p. 146.

- ↑ Boswell 2021, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Boswell 2021, pp. 2–4.

- ↑ Boswell 2021, pp. 14–17.

- ↑ Boswell 2021, pp. 17, 21, 185.

- ↑ Boswell 2021, p. 29.

- ↑ Boswell 2021, p. 45.

- ↑ Boswell 2021, pp. 73–75.

- 1 2 Van der Bijl 1999, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 Boswell 2021, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Boswell 2021, p. 88.

- ↑ Thompson 1985, p. 39.

- ↑ Boswell 2021, pp. 85–87.

- 1 2 Thompson 1985, pp. 111–112.

- 1 2 3 Boswell 2021, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Boswell 2021, p. 110.

- ↑ Bilton & Kosminsky 1990, p. 195.

- ↑ Thompson 1985, p. 96.

- ↑ Boswell 2021, pp. 89–93.

- ↑ Arostegui 1997, p. 205.

- 1 2 Boswell 2021, p. 115.

- ↑ Ruiz Moreno 1986, pp. 253–271.

- 1 2 Boswell 2021, p. 78.

- ↑ Ruiz Moreno 1986, p. 271.

- 1 2 3 Boswell 2021, pp. 93–95.

- ↑ Thompson 1985, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ "El heroico valor en combate". gaceta.marinera.com.ar. Argentina Ministerio de Defensa. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ↑ "Héroes de Malvinas, Héroes de la Patria: Teniente Primero Ernesto Espinosa". www.argentina.gob.ar. 30 May 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ↑ "No. 49134". The London Gazette (1st supplement). 8 October 1982. p. 12843.

- ↑ "Compañías de Comandos del Ejército Argentino en acción". paralibros.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ "Malvinas: identificaron a Mateo Sbert, el sargento que murió en la histórica batalla de "Top Malo House"". lanacion.com.ar (in Spanish). 30 October 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ "Voladura del Puente Fitz Roy en la Campaña de Malvinas". laperlaaustral.com.ar (in Spanish). 24 June 2019. Archived from the original on 23 October 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ Van der Bijl 1999, pp. 153–154.

- ↑ Van der Bijl 2020, p. 186.

References

- Arostegui, Martin (1997). Twilight Warriors. New York: St. Martin's Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-312-96493-1. OCLC 38927807.

- Bilton, Michael; Kosminsky, Peter (1990). Speaking Out. London: Grafton books. ISBN 978-0-586-20897-7. OCLC 490481589.

- Boswell, Rod (2021). Mountain Commandos at War in the Falklands. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-52679-162-7. OCLC 1242830431.

- Brown, David (1987). The Royal Navy and the Falklands War. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-09-957390-6. OCLC 780526247.

- Delves, Cedric (2018). Across an Angry Sea: The SAS in the Falklands War. London: Hurst & Company. ISBN 978-1-78738-112-4. OCLC 1046610527.

- Freedman, Lawrence (2005). The Official History of the Falklands Campaign: War and Diplomacy. Government official history series. Vol. 2. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7146-5207-8. OCLC 799240030.

- Ruiz Moreno, I.J. (1986). Comandos en acción: El Ejército en Malvinas (in Spanish). Madrid: Editorial San Martín. ISBN 978-84-7140-253-0. OCLC 18514413.

- Thompson, Julian (1985). No Picnic: 3 Commando Brigade in the South Atlantic. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-436-52052-5. OCLC 464153678.

- Van der Bijl, Nick (1999). Nine Battles to Stanley. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-0-85052-619-6. OCLC 43032276.

- Van der Bijl, Nick (2020). My Friends, The Enemy: Life in Military Intelligence During the Falklands War. Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-9418-4. OCLC 1105321287.

Further reading

- Losito, Horacio [in Spanish] (2006). Asi peleamos, Malvinas: Testimonios de veteranos del Ejército (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Biblioteca Soldados. ISBN 987-97861-1-4. OCLC 44806893.