| Battle of Tourcoing | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Flanders campaign in the War of the First Coalition | |||||||

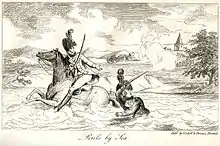

Frederick, Duke of York, narrowly escapes capture after his column is isolated and crushed at the battle of Tourcoing | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of the North | Coalition Army | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 70,000-82,000 | 74,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

3,000 casualties 7 guns |

4,000 killed or wounded 1,500 captured 60 guns | ||||||

Location within Europe | |||||||

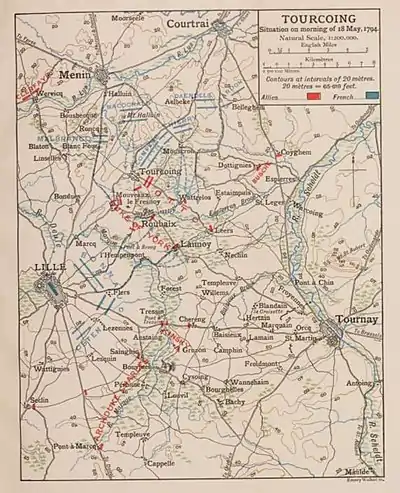

The Battle of Tourcoing (17–18 May 1794) saw a Republican French army directed by General of Division Joseph Souham defend against an attack by a Coalition army led by Emperor Francis II and Austrian Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld. The French army was temporarily led by Souham in the absence of its normal commander Jean-Charles Pichegru. Threatened with encirclement, Souham and division commanders Jean Victor Marie Moreau and Jacques Philippe Bonnaud improvised a counterattack which defeated the Coalition's widely separated and poorly coordinated columns. The War of the First Coalition action was fought near the town of Tourcoing, north of Lille in northeastern France.

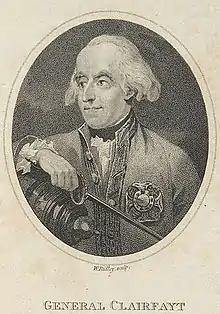

The Coalition battle plan drawn up by Karl Mack von Leiberich launched six columns that attempted to envelop part of the French army holding an awkward bulge at Menen (Menin) and Kortrijk (Courtrai). On 17 May, the French defeated Georg Wilhelm von dem Bussche's small column while the columns of Count François of Clerfayt, Count Franz Joseph of Kinsky, and Archduke Charles made slow progress. On 18 May, Souham concentrated his main strength on the two center columns under the command of Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany and Rudolf Ritter von Otto, inflicting a costly setback on the Coalition's Austrian, British, Hanoverian, and Hessian troops.

The action is sometimes referred to as the Battle of Tourcoin, a gesture towards the English pronunciation of the town.[1]

Background

Armies

For the campaign of 1794, Lazare Carnot of the Committee of Public Safety devised a strategy whereby the French armies would envelop both flanks of the Coalition army defending the Austrian Netherlands. The French left wing was ordered to seize Ypres, then Ghent, then Brussels. Meanwhile, the right wing was to thrust at Namur and Liège, cutting the Austrian line of communications to Luxembourg City. The French center would defend the line between Bouchain and Maubeuge.[2] On 8 February 1794, new commander Jean-Charles Pichegru arrived at Guise to assume leadership of the Army of the North.[3] In March 1794, the Army of the North numbered 194,930 men, including 126,035 soldiers available for the field. Pichegru also had authority over the subordinate Army of the Ardennes which counted 32,773 men, for a combined total of 227,703 troops.[4]

At the beginning of April, the Coalition army occupied the following positions. Not counting garrisons, the right wing numbered 24,000 Austrians, Hessians, and Hanoverians under Clerfayt with headquarters at Tournai. Ludwig von Wurmb commanded 5,000 soldiers at Denain. The 22,000 men of the right center were led by the Duke of York at Saint-Amand-les-Eaux. Headquartered at Valenciennes, Prince Coburg commanded the 43,000 troops of the center. William V, Prince of Orange commanded 19,000 Dutch of the left-center at Bavay. Franz Wenzel, Graf von Kaunitz-Rietberg led 27,000 Austrian and Dutch troops on the left wing at Bettignies. Another 15,000 Austrians under Johann Peter Beaulieu guarded the far left from Namur to Trier.[5] Emperor Francis arrived at Valenciennes on 14 April and Coburg recommended that the fortress of Landrecies be reduced.[6] On 21 April the Siege of Landrecies began; it ended on 30 April with a French capitulation.[7]

Operations

In the Battle of Beaumont on 26 April, Coalition cavalry routed a 20,000-man French column that tried to relieve Landrecies. The Allies inflicted 7,000 casualties on the French and captured their commander René-Bernard Chapuy with Pichegru's plans for attacking coastal Flanders. With his enemy's plans before him, Coburg immediately sent William Erskine with a considerable reinforcement for the right wing. Clerfayt, who had been drawn to the east, was ordered back to cover the western flank. It was too late; Pichegru had already attacked. Pierre Antoine Michaud's 12,000-man division advanced from Dunkirk toward Nieuport and Ypres. Jean Victor Marie Moreau's 21,000-strong division from Cassel swept past Ypres and laid siege to Menen (Menin). Accompanied by Pichegru, Souham's 30,000-man division started from Lille and seized Kortrijk (Courtrai).[8] On 29 April, Souham defeated Clerfayt's outnumbered force in the Battle of Mouscron. That night, the Allied garrison abandoned Menin and successfully broke through the French investment.[9] By taking Menin and Courtrai, the French had pierced the Coalition front.[10]

.JPG.webp)

When Landrecies surrendered on 30 April, Coburg sent York west to reinforce Clerfayt. The two Coalition forces joined at Tournai: York led 18,000 soldiers, Clerfayt commanded 19,000 troops (though one British brigade was still en route), and Johann von Wallmoden had 4,000–6,000 men.[11] The two Coalition commanders worked out a plan where Clerfayt would attack Courtrai from the north while York would strike from the direction of Tournai and cut off the French from Lille.[12] At about the same time, Pichegru ordered Jacques Philippe Bonnaud's large division (formerly Chapuy's) from Cambrai to Lille.[13] In the Battle of Courtrai on 10 May, Bonnaud's 23,000 troops advanced to attack the Coalition troops holding Tournai. York turned the French right flank with a mass of cavalry. The French infantry repelled a series of cavalry charges, but the Allied horsemen finally prevailed after receiving artillery support; the French were forced to retreat.[14] Also on 10 May, Clerfayt attacked Dominique Vandamme's brigade (of Moreau's division) at Courtrai but failed to capture the place. The next day, Souham reinforced Vandamme with part of his division.[13] On 11 May, the French drove back Clerfayt who retreated north to Tielt. Realizing that the French forces in the area badly outnumbered him, York halted and called for reinforcements.[15]

After the fall of Landrecies, the Coalition high command was torn between moving the army west to save coastal Flanders or east to assist Kaunitz on the Sambre River. They considered a feint attack toward Cambrai or investing Avesnes-sur-Helpe. When York's appeal for help arrived, Kinsky was sent to Denain with 6,000 troops so that Wurmb's force could march to Tournai. Then Kaunitz announced that he was hard-pressed.[15] Coburg told Francis II that he must decide whether the main army should move to Flanders or to the Sambre. On 13 May, Kaunitz won the Battle of Grandreng so the next day the emperor decided the main army must move west toward Flanders. Even so, Orange and 8,000 troops were left behind to protect Landrecies.[16] Despite the odds, York was determined to attack on 15 May, in cooperation with Clerfayt. In the night of 14 May, a message arrived from Francis telling York that he would soon arrive and the Allies would launch a major attack.[17] Francis joined York in Tournai on 15 May while Archduke Charles and the main Coalition army arrived at Saint-Amand-les-Eaux.[18]

As an added distraction, the Kościuszko Uprising broke out in Poland on 25 March and quickly spread. This event took Francis, Catherine I of Russia and Frederick William II of Prussia completely by surprise. Catherine asked Francis for help and Prussia withdrew 20,000 soldiers from the war against France.[16] At imperial headquarters, one faction led by Coburg wanted to continue the war with France, while another faction wanted Austria's energies directed toward Poland in order to thwart its rival Prussia.[18]

Plans

On 16 May, staffs of the Coalition army drew up a battle plan. Coburg's chief-of-staff Mack called it the Vernichtungsplan (Annihilation Plan). Mack is usually credited with its development, but the strategic concept may have been York's. The plan's stated goal was, "to act upon the enemy's communications between Lille and Menin and Courtrai, to defeat his armies that he has advanced upon the Lys and to drive him out of Flanders".[17] The battlefield was bounded on the north by the Lys River and on the east by the Scheldt River. The Marque River flows north from Pont-à-Marcq until it empties into the Deûle which is a tributary of the Lys. The Marque could only be crossed by bridges because of its soft bottom and swampy banks. The Spiere brook rises near Roubaix and flows eastward into the Scheldt at Spiere. The land is mostly level, but there were many villages and farmhouses enclosed by hedges. It was difficult to move off-road, but roads were plentiful in the region and the main roads were wide. The terrain was not favorable for cavalry operations, giving the French an advantage.[19]

.JPG.webp)

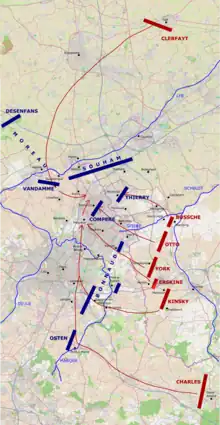

According to historian John Fortescue, the Allies divided their 62,000-man army (including 12,000 cavalry) into six columns. Bussche led 4,000 Hanoverians[20] in 5 battalions and 8 squadrons. These included 2 battalions of the 1st Infantry Regiment, the 1st and 4th Grenadier Battalions, and 2 squadrons each of the 1st and 7th Cavalry and the 9th and 10th Light Dragoon Regiments.[21][note 1] Otto commanded 10,000 men in 12 battalions and 10 squadrons. York directed 10,000 soldiers in 12 battalions and ten squadrons.[22] York's column included the following British troops: 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Foot Guards, Guards Flank Battalion, 14th Foot, 37th Foot, 53rd Foot, Flank Battalion, 7th, 15th, and 16th Light Dragoons.[21] Kinsky led 9,000 men in 10 battalions and 16 squadrons and Charles commanded 14,000 men in 17 battalions and 32 squadrons. Clerfayt had 16,000 troops[22] in 25 battalions and 28 squadrons.[1] In addition, a cavalry reserve of 16 British squadrons under Erskine was assembled near Hertain.[23]

Ramsay Weston Phipps stated that the Allies employed 73,350 soldiers. Five columns would attack from the Tournai area and were numbered from north to south. Bussche's first column consisted of 4,000 Hanoverians and was ordered to move north from Warcoing to Dottignies, then west to Mouscron.[24] However, one-third of Bussche's column was sent on a subsidiary mission toward Courtrai.[23] Otto's second column counted 10,000 soldiers and was sent northwest through Leers, Wattrelos, and Tourcoing. York's third column numbered 10,750 troops and was directed to advance abreast of Otto's column from Templeuve through Lannoy, Roubaix, and Mouvaux. Kinsky's fourth column had 11,000 men and would start from Marquain and force its way across the Marque River at Bouvines. Charles' fifth column was 18,000-strong.[24] Starting from Saint-Amand-les-Eaux, it would march to Pont-à-Marcq[25] while sending a detachment to preserve contact with Kinsky. It was ordered to force a passage across the Marque and turn north, join Kinsky's column, and finally join hands with York near Mouvaux.[23] The sixth column under Clerfayt counted 19,600 men and was instructed to move south from Tielt to Wervik, cross the Lys, and press southeast toward Tourcoing.[26]

On 13 May, Pichegru left the scene to pay a visit to his right wing, leaving Souham in temporary command.[27] The Army of the North included the divisions of Souham (28,000), Moreau (22,000), Bonnaud (20,000) and Pierre-Jacques Osten (10,000), altogether 82,000 soldiers. Osten's soldiers were posted at Pont-à-Marcq. Bonnaud's men bivouacked at Sainghin-en-Mélantois with detachments at Lannoy and Pont-à-Tressin. Souham's and Moreau's troops were on the south bank of the Lys between Courtrai and Aalbeke. Jean François Thierry's brigade was located at Mouscron. Louis Fursy Henri Compère's brigade occupied Tourcoing to preserve the connection with Bonnaud.[20] As recently as 10 May, Souham's division consisted of the following brigades: Étienne Macdonald, Herman Willem Daendels, Jan Willem de Winter, Henri-Antoine Jardon, and Philippe Joseph Malbrancq. Compère and Thierry each led independent brigades.[28][note 2] Bonnaud's division was made up of the brigades of Jean-Baptiste Salme, Nicolas Pierquin, and Pierre Nöel, while the cavalry was grouped under Antoine-Raymond Baillot-Faral.[29] Moreau had only the brigades of Dominique Vandamme and Nicolas Joseph Desenfans, and the latter unit was observing Ypres and not in close contact.[30] Fortescue credited Vandamme with 8,000 troops,[31] while Steve Brown stated that he commanded 12,000 troops.[32]

Battle

17 May: Clerfayt, Kinsky, and Charles

Problems with the Allied plan began to appear at once. Clerfayt did not receive his orders until late in the morning on 16 May and his column did not start until the evening. The sandy roads slowed the march so that his troops did not reach Wervik until the afternoon of 17 May. Clerfayt found the bridge over the Lys was well-fortified by the French. When he called for his pontoon train, it was found that it had been left in the rear by some blunder and the column was delayed several hours.[33] It was 1:00 am on 18 May before the pontoon bridge was ready to use.[34] Only a few battalions crossed, but most of Clerfayt's men camped on the north bank that night.[25]

The other columns encountered a heavy fog early on 17 May. While Kinsky had only 7 mi (11 km) to march from Froidmont to Bouvines, Charles' column was expected to march 15 mi (24 km) from Saint-Amand to Pont-à-Marcq.[25] After receiving a message from Charles that his column would not be able to reach Pont-à-Marcq by 6:00 am on 17 May, Kinsky delayed his march. Nevertheless, Kinsky eventually moved forward and drove the French from Bouvines. His troops were unable to cross the Marque because the French had broken the bridge and covered the crossing with a battery of heavy guns.[35] Erskine's reserve cavalry was supposed to support York, but it took the wrong road and joined Kinsky's column instead.[36] Charles' column left Saint-Amand at 10:00 pm on 16 May and fought its way across the river at Pont-à-Marcq at 2:00 pm on 17 May. His soldiers reached Lesquin but were too tired to go any farther. Charles' advance forced Bonnaud to abandon Sainghin and withdraw to Lille, allowing Kinsky to repair the bridge at Bouvines. However, Kinsky cautiously had his soldiers camp on the east bank of the Marque that night.[35]

17 May: Bussche, Otto, and York

During the night, Bussche assembled at Saint-Leger to the west of Warcoing. On 17 May, his column advanced to Mouscron and captured the place.[25] Bussche was stoutly opposed by Thierry's brigade, which was reinforced by Souham.[37] Compère counterattacked, recovering Mouscron and throwing Bussche's troops back to Dottignies and Herseaux.[38] Most of the 1st Hanoverian Infantry was captured.[39] Otto's column successively drove Compère's brigade from Leers, Wattrelos, and Tourcoing. However, this merely pushed Compère's men back to Mouscron where they were able to join Thierry's brigade and help defeat Bussche.[25]

York's column moved through Templeuve to attack Lannoy with the Guards brigade, supported by the light dragoons. The French fled so quickly that they suffered very few casualties. York left two Hessian battalions to hold Lannoy and pressed onward to Roubaix. Though the place was well-defended, the Guards brigade chased the French out of Roubaix.[25] Around 5:00–6:00 pm, York found that Mouscron was still held by the French and decided to halt his advance at Roubaix.[38] He had also heard nothing from Otto or Kinsky. However, Emperor Francis ordered York to continue his march to Mouvaux and overrode his objections. Therefore, the Guards brigade under Ralph Abercromby assaulted the village with the bayonet, driving the French from their well-fortified positions and capturing 3 cannons. The 7th and 15th Light Dragoons circled around Mouvaux and caught the retreating French, cutting down 300 of them. A group of light dragoons actually galloped into the French camp at Bondues and caused a minor panic.[40]

17 May: Evening

On the morning of 17 May, the French generals had no idea of the trap being sprung around them. They were only aware of the movements of Clerfayt's column, so they moved the divisions of Souham and Moreau to the north bank of the Lys. As reports of the Allied advance reached them, the French commanders reacted. Only Vandamme's brigade was left on the north bank to observe Clerfayt, while the rest of the troops were recalled to the south bank.[35] Souham, Souham's staff officer Jean Reynier, Moreau, Macdonald, Macdonald's staff officer Pamphile Lacroix, and Pichegru's chief-of-staff Jean Jacques Liébert[27] met at Menin in council that evening to decide on a plan.[35][note 3] Simply put, Moreau would defend the line of the Lys against Clerfayt's advance while Souham struck southwest from Courtrai and Bonnaud attacked northeast from Lille. Early in the morning they would hurl approximately 40,000 troops at the 20,000 Allies under York and Otto. Meanwhile, the division of André Drut at Douai would mount a demonstration to the northeast and the Lille garrison would feint to its southeast.[27] Moreau remarked, "It would require a piece of good fortune, on which we cannot count, to prevent half my division and myself being sacrificed according to this plan, but still it is the best which can be proposed, and consequently it should be adopted."[30]

On the evening of 17 May, Coalition headquarters knew that Bussche failed to capture Mouscron and that Charles was out of position. It had no news at all from Clerfayt.[41] Uneasy that his left flank was not covered, at 9:00 pm York asked permission to withdraw to Lannoy. Mack refused, promising York that Charles and Kinsky would be up in time. At 1:00 am Mack dispatched Captain Franz von Koller to Charles with orders to march to Lannoy immediately. At 4:00 am when Koller arrived at Charles' headquarters, his staff refused to awaken the general. In fact, Charles, who suffered from epilepsy, had a seizure. However, the staff failed to notify the next in command. At 3:00 am, Mack sent a fresh set of orders instructing Charles to leave 10 battalions and 20 squadrons to watch Lille, and march with Kinsky to Lannoy.[42]

York and Otto were ordered to attack Mouscron at noon. The Coalition staff officers apparently never considered that the positions of the second and third columns invited a French counterattack. Bussche's mauled units defended Dottignies and Coyghem. Otto's column was distributed with 7½ battalions and 3 squadrons at Tourcoing, 2 battalions at Wattrelos, and 3 battalions and 3 squadrons at Leers. York's column was spread out with Abercromby's Guards brigade and the 7th and 15th Light Dragoons at Mouvaux,[41] 4 Austrian battalions and the 16th Light Dragoons defended Roubaix, 2 Hessian battalions held Lannoy, and Henry Edward Fox's brigade (14th, 37th, and 53rd Foot) deployed west of Roubaix, watching Lille. Patrolling the area were 4 Austrian squadrons. The nearest unit belonging to Kinsky's column was 4 mi (6 km) distant at Pont-à-Tressin.[43] This was Wurmb's Hessian brigade.[36]

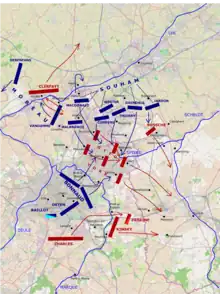

18 May: French counterattack

Malbrancq's brigade lay south of Menin at Roncq and Blancfour. To its east, Macdonald's brigade was posted at Halluin. The brigades of Daendels and Jardon deployed 3 mi (5 km) farther east between Aalbeke and Belleghem. The brigades of Compère and Thierry at Mouscron plugged the space between Macdonald and Daendels. The divisions of Bonnaud and Osten were near Flers.[41] At 3:00 am on 18 May, the French army began moving into its assault positions.[43] Osten's division and Baillot's cavalry were left to fend off any advances from Kinsky and Charles[37] in the area of Flers and Lezennes. Bonnaud split his 18,000 troops into two columns: the northern moved through Pont-a-Breug (modern Flers-Breucq) toward Roubaix, the southern moved through L'Hempenpont toward Lannoy. Malbrancq moved south from Roncq toward Mouvaux. Macdonald advanced from Halluin against the west side of Tourcoing. Compère marched from Mouscron against Tourcoing's north side. Thierry moved from Mouscron and Daendels marched from Aalbeke; both attacked Wattrelos. Jardon advanced from Belleghem against Dottignies[43] where his troops dueled with Bussche's Hanoverians the rest of the day.[31]

The French assault hit Otto at dawn and the local commander Paul Vay De Vay asked York to send help. York sent 2 battalions of Infantry Regiment Grand Duke of Tuscany Nr. 23[44] with orders to return if they were too late to save the town.[43] In fact, by the time they reached Tourcoing, the place had already fallen to the French and they never returned to York. The Austrian commander at Tourcoing, Eugen von Montfrault took a defensive position east of the town, but he was compelled to retreat when a French battery opened fire from the north. Montfrault formed his troops into a large square, with 4 battalions and light artillery in front, 1 battalion protecting each flank, cavalry guarding the rear, heavy artillery and wagons in the center, and light infantry holding a skirmish line. Montfrault started withdrawing in this formation about 8:15 am. The 2 Hessian battalions in Wattrelos, outnumbered 6-to-1, were forced to retreat at 8:00 am. With the help of a 2-company force sent by Otto, the Hessians escaped to Leers. Unable to retreat through Wattrelos, Montfrault's still-intact square turned into a secondary road that passed west of the town.[45] Here, Montfrault was hit by Bonnaud's troops from the south and Souham's men from the north and west. The square formation broke up and the Austrians fled to Leers.[46]

Between 6:00 and 7:00 am, Bonnaud's division began attacking York's troops at Roubaix and Lannoy; this was a little after Otto's column came under assault. Soon after, Malbrancq's brigade attacked Mouvaux from the north and some of the French formations that had captured Tourcoing began to appear north of Roubaix. York fruitlessly sent couriers to recall the two battalions sent to Otto. At Mouvaux, the defenses faced east with the line bent back to the hamlet of Le Fresnoy to defend against attack from the north. Fox's brigade faced west toward Lille. The remaining Austrian battalions were posted near Roubaix, to Fox's right rear. These units were soon swept away by the French assault[45] partly because Bonnaud's troops moved through the gaps left by the two missing battalions. By this time, the brigades of Thierry and Daendels were advancing from Wattrelos to strike York's column from the north. The French attackers completely isolated Abercromby's Guards brigade and York sent orders for it to fall back to Roubaix.[46]

Abercromby's Guards withdrew to Roubaix protecting a convoy of artillery, with the 7th and 15th Light Dragoons acting as the rearguard. Roubaix was still held by a dismounted squadron of the 16th Light Dragoons. The column of guns and the Guards brigade exited the walled town safely and turned right into the road leading to Lannoy. As the Austrian Hussars emerged, a nearby French gun took the column in enfilade, causing havoc. The Hussars tried in vain to find another escape route, but finally galloped down the road through a gauntlet of fire. Unknown to the horsemen, the artillery train ahead of them had been ambushed and the drivers panicked,[47] abandoning their guns and limbers in the road and fleeing with the horses.[48] After riding 300 to 400 yd (274 to 366 m), the cavalry plowed into the artillery blockade, throwing horses and riders to the ground, as the French peppered them with musketry.[47] The British camp followers were also killed in the chaos. Robert Wilson watched a soldier's wife kiss her baby and then throw it in a ditch. "She frantically rushed forwards and, before she got ten yards, was rent in pieces by a discharge of grape that entered her back." Wilson claimed that York's column lost 56 guns.[49]

Eventually the Guards cleared the immediate area and the rest of the troops recovered themselves. As the column neared Lannoy, it was believed to be held by the French. In fact, the 2 battalions of Hessians were still holding out.[50] Seeing some cavalrymen and believing them to be Hessians, William Congreve allowed them to approach; they were French and cut the harnesses to the gun teams. The Guards and the cavalry marched cross-country to Marquain. The Guards brigade lost 196 officers and men[51] while the light dragoons lost 52 men and 92 horses. The British artillery lost 19 out of 28 guns.[31] The Hessians were forced to abandon Lannoy soon after; they sustained 330 casualties out of 900 men.[51]

Fox's brigade defended itself successfully from Bonnaud's troops, but found itself surrounded. The brigade withdrew in good order, reaching the main road near Lannoy. Soon afterward, the brigade found that the French had set up a battery in the road blocking their escape. At this moment, a French emigrant who had enlisted in the 14th Foot offered to guide Fox's soldiers cross-country. Though continually harassed by French skirmishers, cannon fire, and cavalry,[46] the British brigade managed to reach Leers and safety. However, it suffered the loss of all its battalion guns but one, and 534 officers and men out of a total of 1,120.[47] York barely evaded capture after starting the day at Roubaix. Finding himself cut off from the forces of Abercromby and Fox, and seeing his Austrian battalions melting away, he took a small escort from the 16th Light Dragoons and rode toward Wattrelos.[46] While riding through that town, York's party was taken under fire by some French soldiers and then they rode cross-country.[52] They came upon a small group of Hessians defending the Spiere brook. York's horse refused to cross the brook, so he waded across, took the horse of an aide-de-camp,[51] and got away to Otto at Leers. Souham later remarked that York, "came within an ace of accompanying his guns to Lille".[52]

18 May: Clerfayt, Kinsky, and Charles

At 7:00 am, Clerfayt's column crossed the Lys near Wervik. His troops marched toward Linselles and Bousbecque where they faced Vandamme's brigade (now on the south bank). Clerfayt drove back Vandamme's right flank and captured 8 guns.[31] Desenfans' brigade retreated southwest to Bailleul when it might have operated against Clerfayt's western flank.[53] An advanced guard composed of one squadron each of the British 8th Light Dragoons and a Hessian cavalry regiment was surrounded by the French. The Coalition troopers gallantly cut their way out of the trap, though they lost two-thirds of their numbers.[54] Vandamme reported that the cavalry got as far as Halluin, causing his artillery to hurriedly withdraw. Two battalions arrived, Vandamme's men steadied, pushed back Clerfayt a distance, and captured a color from the 8th Light Dragoons. Thinking that the French received 5,000 reinforcements, Clerfayt pulled back to Wervik while hoping to renew the offensive on 19 May. In fact, Vandamme's brigade had fought alone.[30]

.jpg.webp)

The French formations did not pursue Otto and York, because of the looming threat from Clerfayt. Souham ordered the brigades of Malbrancq, Macdonald, and Daendels to march against Clerfayt on the evening of 18 May. Bonnaud, Thierry, and Compère were left to hold Wattrelos and Lannoy. That night, Clerfayt received notice of the Coalition defeat. He withdrew across the Lys and continued to Roeselare, carrying off 300 prisoners and 7 guns. The French tried to move through Menin to intercept Clerfayt, but Hanoverian cavalry repulsed the leading elements.[30]

When Kinsky was urged by the emperor's aide-de-camp to push forward to Sainghin, he replied, "Kinsky knows what he has to do". Nevertheless, his column remained inactive.[53] At 6:00 am, one of his subordinates asked for orders and Kinsky announced that he was sick and no longer in command.[31] At 2:00 pm, Kinsky heard about the defeat of York and Ott and withdrew.[53] Charles received early-morning orders to march to Lannoy, only 6 mi (10 km) distant. Yet, his troops did not move until noon and did not reach the Tournai-Lille highway until 3:00 pm. By then, new orders arrived directing him to fall back to Tournai. Charles later proved himself to be a gifted commander, but the inertia of Kinsky and Charles on this day was so astounding that it led Fortescue to opine that their lack of urgency was encouraged at headquarters by generals in the faction of Johann Amadeus von Thugut, the Austrian prime minister, in an act of deliberate betrayal to sabotage the English so Austria would not be kept in the war against France, and could focus instead on countering Prussia in Poland, his preferred foreign policy priority.[31] However, Fortescue's chauvinistic assertion was based on the claim that Austrian headquarters had not urged Kinsky and Charles forward, whereas they actually had tried.[42][53] Phipps wrote of Kinsky and Charles, "As far as the battle was concerned, the 29,000 men of these two columns might have been a hundred miles away".[55]

Results

Gaston Bodart stated Allied losses at Tourcoing as 4,000 killed or wounded and 1,500 captured. He gave French casualties as 3,000.[56] According to Digby Smith, the French suffered a loss of 3,000 casualties, including brigadier Pierquin killed, and seven cannons.[21] The Allies lost 4,000 killed and wounded, with 1,500 men captured. There was no pursuit of the defeated Allied main body. Of his 74,000 Allied soldiers, Coburg only committed 48,000 to battle.[39] Edward Cust estimated that the Coalition lost 3,000 men and 60 guns.[54] H. Coutanceau believed that York's column lost 53 officers, 1,830 men, and 32 guns, while T. J. Jones only admitted a loss of 65 killed and 875 wounded and missing.[49]

On 27 May, Coburg wrote to York that Emperor Francis was perfectly satisfied with his actions at Tourcoing, and that York had executed all his orders properly.[48] Francis and the Austrian generals were discouraged at the result. The morale of the British soldiers remained intact, but the men were bitter at their Austrian allies for apparently abandoning them.[57] On 23 May, Mack resigned his position of chief-of-staff and left the army. In his opinion, the reconquest of the Austrian Netherlands was a lost cause. The following day, a gloomy council of war was held by Francis, with only York asking for a renewal of the attack on the French. Nevertheless, Kaunitz again beat the French right wing on the Sambre at the Battle of Erquelinnes.[58] Pichegru rejoined his army on 19 May and began planning for an attack on the Coalition army that would result in the Battle of Tournai.[59]

Notes

- Footnotes

- Citations

- 1 2 Cust 1859, p. 198.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, p. 86.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, p. 275.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, p. 284.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, p. 87.

- ↑ Smith 1998, p. 76.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, pp. 100–102.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, p. 293.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, p. 104.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, p. 105.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, p. 106.

- 1 2 Phipps 2011, p. 294.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, pp. 106–108.

- 1 2 Fortescue 2016, p. 108.

- 1 2 Fortescue 2016, p. 109.

- 1 2 Brown 2021, p. 136.

- 1 2 Fortescue 2016, p. 110.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, pp. 110–111.

- 1 2 Fortescue 2016, p. 111.

- 1 2 3 Smith 1998, p. 79.

- 1 2 Fortescue 2016, pp. 111–112.

- 1 2 3 Fortescue 2016, p. 112.

- 1 2 Phipps 2011, pp. 296–297.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fortescue 2016, p. 113.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, p. 296.

- 1 2 3 Phipps 2011, p. 299.

- ↑ Brown 2021, p. 131.

- ↑ Brown 2021, p. 132.

- 1 2 3 4 Phipps 2011, p. 300.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Fortescue 2016, p. 127.

- ↑ Brown 2021, p. 150.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, p. 297.

- 1 2 3 4 Fortescue 2016, p. 115.

- 1 2 Cust 1859, p. 200.

- 1 2 Cust 1859, p. 199.

- 1 2 Phipps 2011, p. 298.

- 1 2 Smith 1998, p. 80.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, p. 114.

- 1 2 3 Fortescue 2016, p. 116.

- 1 2 Phipps 2011, pp. 298–299.

- 1 2 3 4 Fortescue 2016, p. 118.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, p. 303.

- 1 2 Fortescue 2016, p. 119.

- 1 2 3 4 Fortescue 2016, p. 122.

- 1 2 3 Fortescue 2016, p. 124.

- 1 2 Phipps 2011, p. 305.

- 1 2 Phipps 2011, p. 306.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, p. 125.

- 1 2 3 Fortescue 2016, p. 126.

- 1 2 Phipps 2011, p. 304.

- 1 2 3 4 Phipps 2011, p. 301.

- 1 2 Cust 1859, p. 201.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, p. 302.

- ↑ Bodart 1908, p. 289.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, p. 130.

- ↑ Fortescue 2016, p. 132.

- ↑ Phipps 2011, p. 309.

References

- Bodart, Gaston (1916). "Losses of Life in Modern Wars: Austria-Hungary, France". Oxford: Clarendon Press. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- Brown, Steve (2021). The Duke of York's Flanders Campaign: Fighting the French Revolution 1793–1795. Havertown, Pa.: Pen and Sword Books. pp. 135–136. ISBN 9781526742704. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- Cust, Edward (1859). "Annals of the Wars: 1783–1795". pp. 198–201. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- Fortescue, John W. (2016) [1906]. The Hard-Earned Lesson: The British Army & the Campaigns in Flanders & the Netherlands Against the French: 1792–99. Leonaur. ISBN 978-1-78282-500-5.

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011) [1926]. The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume I The Armée du Nord. US: Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908692-24-5.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

- Bodart, Gaston (1908). Militär-historisches Kriegs-Lexikon (1618-1905). Wien und Leipzig, C. W. Stern.

Further reading

- Black, Jeremy (1999). Britain as a Military Power, 1688–1815. Routledge. ISBN 1-85728-772-X.

- Belloc, Hilaire. Tourcoing Project Gutenberg eBook

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 103.

- Fortescue, Sir John William (2014). A History Of The British Army – Vol. IV – Part One (1789–1801). Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78289-130-7.

- Smith, Digby George (2003). Charge!: Great Cavalry Charges of the Napoleonic Wars. Greenhill. ISBN 978-1-85367-541-6.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-672-5.

External links

Media related to Battle of Tourcoing at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Tourcoing at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Second Battle of Boulou |

French Revolution: Revolutionary campaigns Battle of Tourcoing |

Succeeded by Battle of Tournay (1794) |