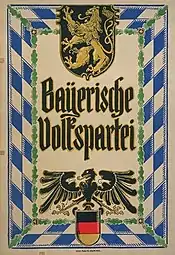

Bavarian People's Party Bayerische Volkspartei | |

|---|---|

| |

| President(s) | Karl Speck (1918–1929) Fritz Schäffer (1929–1933) |

| Founded | November 1918 |

| Dissolved | 4 July 1933 |

| Split from | Centre Party |

| Succeeded by | Christian Social Union in Bavaria, Bavaria Party (not legal successors) |

| Headquarters | Munich, Germany |

| Paramilitary wing | Bayernwacht |

| Ideology | Political Catholicism Bavarian regionalism Christian democracy Conservatism (German)[1] |

| Political position | Centre-right[2] |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Colours | Cyan White |

| Party flag | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

The Bavarian People's Party (German: Bayerische Volkspartei; BVP) was a Catholic political party in Bavaria during the Weimar Republic. After the collapse of the German Empire in 1918, it split away from the national-level Catholic Centre Party and formed the BVP in order to pursue a more conservative and particularist Bavarian course.[3] It consistently had more seats in the Bavarian state parliament than any other party and provided all Bavarian minister presidents from 1920 on. In the national Reichstag it remained a minor player with only about three percent of total votes in all elections. The BVP disbanded shortly after the Nazi seizure of power in early 1933.

Founding

There had been a Bavarian wing of the Centre Party throughout the years of the German Empire. After Germany's defeat in World War I and the outbreak of the German Revolution of 1918–1919, leading Bavarian members of the Centre Party around Georg Heim founded the Bavarian People's Party in Regensburg on 12 November 1918 as the Bavarian party of political Catholicism.[4] Two main factors drove the split from the Centre Party. The first was the Bavarian members' emphasis on federalism at the national level, in contrast to the Centre that under the leadership of Matthias Erzberger favored a more centralized national government. The second factor was the Bavarians' clearly more conservative stance, including its assessment of the ongoing revolution which was being led by the Social Democratic Party (SPD).[3] The founding members of the BVP included the party's agrarian wing and, after some resistance, the workers' representatives.[5] The BVP's founding program called for a parliamentary government at the Reich level with a strongly federalist structure, the abolition of "Prussian supremacy", voting rights for women and the introduction of plebiscites. At the party level it strove for a corporative structure, with a "farmers' chamber" (Bauernkammer) as the first step. Half of all committee members and parliamentary candidates at both the national and local level had to be members of BVP-affiliated professional organizations. Party leadership was drawn mostly from clerics, the nobility and the middle class.[5]

Electoral results

The BVP, with about 55,000 members and 2,500 local chapters,[3] was the most widely elected party in all five Bavarian state elections during the Weimar Republic and was represented in all state governments. Most were coalitions with the Bavarian Peasants' League (Bauernbund) and the Protestant Bavarian Middle Party (Bayerischen Mittelpartei),[5] which after 1920 was the Bavarian branch of the strongly nationalist German National People's Party (DNVP). The BVP provided the minister president four times: Gustav Ritter von Kahr[6] (1920–1921), Hugo Graf von Lerchenfeld (1921–1922), Eugen von Knilling (1922–1924) and Heinrich Held (1924–1933). Kahr and Lerchenfeld had only loose ties to party.[5]

| Party | 1919 | 1920 | 1924 | 1928 | 1932 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bavarian People's Party (BVP) | 35.0 | 39.4 | 32.8 | 31.6 | 32.6 |

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | 33.0 | 16.4 | 17.2 | 24.2 | 15.5 |

| German Democratic Party (DDP) | 14.0 | 8.1 | 3.2 | – | |

| Bavarian Peasants' League (BB) | 9.1 | 7.9 | 7.1 | 11.5 | 6.5 |

| German People's Party (DVP) | 5.8 | 13.5 | 9.7[lower-alpha 1] | 3.3 | – |

| Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) | 2.5 | 12.9 | – | – | |

| Communist Party of Germany (KPD) | 1.7 | 8.3 | 3.8 | 6.6 | |

| Völkischer Block (VSB) | 17.1 | – | |||

| German National People's Party (DNVP) | see DVP | 9.3 | 3.3 | ||

| Nazi Party (NSDAP) | 6.1 | 32.5 |

- ↑ Combined German National People's Party and German People's Party

At the national level, the BVP and the Centre formed an electoral alliance for the January 1919 election to the Weimar National Assembly that drew up the Weimar Constitution and served as Germany's interim parliament until the new constitution went into effect. The two parties also had a joint parliamentary group until 1920. After that the relationship between the sister parties deteriorated and led to competitive candidacies in some elections, although from 1927 on there was again a rapprochement.[3]

The BVP participated in various national governments and provided ministers in the cabinets of Wilhelm Cuno, Wilhelm Marx (first), third and fourth cabinets), Hans Luther (first) and second cabinets), Hermann Müller (second cabinet), and Heinrich Brüning (first) and second cabinets). Erich Emminger was the highest ranking, serving as the Reich minister of justice in 1923–1924.

| 1919 | 1920 | May 1924 |

Dec 1924 |

1928 | 1930 | Jul 1932 |

Nov 1932 |

Mar 1933 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.2 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 2.7 |

Political activity

BVP Minister President Kahr was responsible for the idea of establishing Bavaria as an Ordnungszelle (cell of order) within the "Marxist chaos" and completely "Judaized" Weimar Republic.[3] He also fostered the growth of the Civil Guard (Einwohnerwehr), which was similar to the Freikorps. Kahr resigned as minister president in 1921 when the Law for the Protection of the Republic forced the Civil Guards to disarm.[8] In 1924 Minister President Knilling appointed Kahr state commissioner general (Generalstaatskommissar) with dictatorial powers. After Kahr immediately imposed a state of emergency in Bavaria, the government in Berlin did the same for all of Germany.[9] Kahr then stopped enforcing the Law for the Protection of the Republic, which increased the punishments for politically motivated acts of violence and banned organizations that opposed the "constitutional republican form of government" along with their printed matter and meetings.[10] In spite of his right-wing stances, he helped put down Adolf Hitler's November 1923 Beer Hall Putsch.[4] Under pressure from Berlin, Kahr was forced to resign as state commissioner general two months later.[11]

The Bayernwacht (Bavaria Watch), the uniformed paramilitary unit of the Bavarian People's Party, was formed in 1925. It disbanded itself in April 1933.[12]

After the stabilization of the political situation in Germany, the BVP pursued a more moderate course under the leadership of Minister President Heinrich Held (1924–1933) and party president Fritz Schäffer. Under Held, the Bavarian conflicts with the Reich government ended, the economy stabilized, the state administration was reformed and infrastructure expanded.[5] At the national level, the BVP voted in 1925 against Centre Party Reich presidential candidate Wilhelm Marx and for Paul von Hindenburg since it feared socialist-driven centralization.[4]

Rise of the Nazi Party and end of the BVP

The strong upsurge of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) that began in 1930 did not affect the BVP to the same extent as other middle class parties – the German National People's Party (DNVP), German People's Party (DVP) and the German Democratic Party (DDP; later DStP) – since it had a rural Catholic core electorate with solid local structures that proved largely resistant to the emerging National Socialist movement. Heinrich Himmler, who had been a member since 1919, resigned from the BVP in 1923.[13]

After the Nazi Party seized power in January 1933, all 19 BVP deputies in the Reichstag voted for the Enabling Act of 1933 that gave Hitler as chancellor the power to make and enforce laws without involving the Reichstag. The Bavarian government underwent Gleichschaltung (lit. 'coordination') – essentially Nazification – on 10 April 1933. On the same day, Reich Interior Minister Wilhem Frick named General Franz Ritter von Epp as Reichsstatthalter (Reich governor) of Bavaria, and Minister President Held was forced out of office.[4] The BVP, many of whose members had been arrested, saw itself as deprived of any possibility of action and dissolved itself on 4 July 1933. All of its arrested politicians were then released.[3]

Successor parties

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Germany |

|---|

|

The Christian Social Union (CSU) and the Bavaria Party were founded after the Second World War. In programmatic terms they can be seen in part as successor organizations to the BVP, but the CSU is not a legal continuation or successor party to the BVP. From 1945 it absorbed most of the German nationalist camp in Bavaria: the Bayerische Mittelpartei (Bavarian Middle Party), which in the Weimar Republic was the Bavarian offshoot of the nationalist German National People's Party (DNVP), parts of the Bavarian Peasants' League and of the urban liberal middle classes. The same was true of the Bavaria Party, whose supporters came partly from the BVP camp and partly from the Peasants' League.

References

- ↑ Stibbe, Matthew (2010). Germany, 1914–1933: Politics, Society and Culture. Pearson Education. p. 79.

- ↑ Stibbe, Matthew (2010). Germany, 1914-1933: Politics, Society and Culture. Pearson Education. p. 59.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Bayerische Volkspartei (BVP)". Deutsches Historisches Museum (in German). 17 September 2014. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Becker, Winfried. "Geschichte der CDU: Bayerische Volkspartei (BVP)". Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (in German). Archived from the original on 24 June 2022. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Friemberger, Claudia (8 June 2022). "Bayerische Volkspartei (BVP)". Das Staatslexicon (in German) (Version Staatslexikon8 online ed.). Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ↑ "Geschichte des bayerischen Parlaments seit 1819: Kahr, Gustav Ritter von". Bavariathek (in German). Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ↑ "Der Freistaat Bayern Landtagswahlen 1919–1933" [The Free State of Bavaria Parliamentary Elections 1919–1933]. gonschior.de (in German). Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ↑ "Gustav Ritter von Kahr 1862–1934". Deutsches Historisches Museum (in German). Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ↑ Winkler, Heinrich August (1993). Weimar 1918–1933. Die Geschichte der ersten deutschen Demokratie [Weimar 1918–1933. The History of the First German Democracy] (in German). Munich: C.H. Beck. pp. 210–211. ISBN 3-406-37646-0.

- ↑ "[Erstes] Gesetz zum Schutze der Republik. Vom 21. Juli 1922" [[First] Law for the Protection of the Republic]. documentArchiv.de (in German). Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ↑ Stehkämper, Hugo (2016). "Marx, Wilhelm". Neue Deutsche Biographie [Online-Version] (in German). Vol. 26. p. 57.

- ↑ Altendorfer, Otto (3 July 2006). "Bayernwacht, 1924–1933". Historisches Lexikon Bayerns (in German). Retrieved 17 January 2023.

- ↑ "Heinrich Himmler". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 17 January 2023.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)